| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

surfresearch.com.au

surfriding in west africa

|

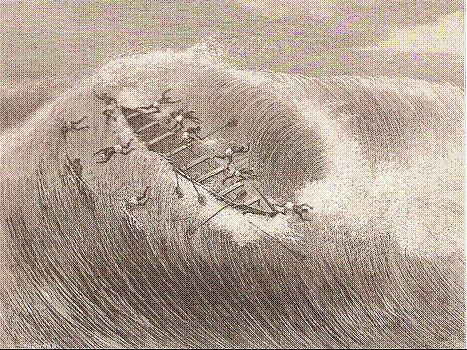

Unaccredited: Surf-boat

wipe-out on a large curling right-hander,

Senegal - Nigeria, circa

1850.

Image contributed by Herve

Manificat, July 2013, publishing details to be confirmed.

In the most

detailed account of African surfriding, John Adams (1823)

writes of Fantee children amusing themselves in the

ocean using terminology reminiscent of many reports from

Polynesia.

On "pieces of

broken canoes, which they launch, and paddle outside of the

surf, when, watching a proper opportunity, they place their

frail barks (boards) on the tops of high waves, which, in

their progress to the shore, carry them along with great

velocity."

That the

surfboards are described as "pieces of broken canoes,"

is significant.

In his seminal

account of surfriding in Tahiti, Joseph Banks (1769)

describes the craft, perhaps a little inaccurately, as "the

stern of an old canoe."

Broken canoes,

most likely splitting longitudinally with the grain and with

the timber already finished, would have been readily recycled,

and one possible option was as a surfboard.

In the Ellice

Islands, Kennedy (1930)

notes that the puke (the shaped bow covering of the

canoe) is often used as a surfboard, and Bligh (1788) reported the

Tahitians, on one occasion, were surfriding on the blades of

their canoe paddles.

(This last case

was probably an aberration given the extreme surf conditions

at the time- during this week every surfboard in Matavai Bay

would have been in high demand).

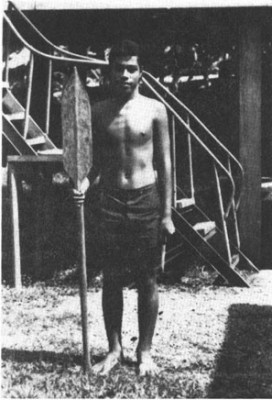

Anuta 1. |

Anuta 2. Plate2. Ashley Raakie,

Honiara, Solomon Islands, August 1988. |

|

Adams

identifies the essential skill in a successful ride following

the take-off; that is, maintaining the board's position in

curl of the wave.

In his own

words, "the principal art of these young canoe men consists in

preserving their seats while thus hurried along, and which

they can only do by steering the planks with such precision,

as to prevent them broaching to ; for when that occurs, they

are washed off, and have to swim to regain them."

Again, similar

to Polynesian accounts, the children, "not more than six or

seven years of age," swim expertly, and surfriding is

community event, the best rides receiving " the plaudits of

the spectators, who are assembled on the beach to witness

their dexterity."

After arriving

by native canoe through "two or three lines of heavy rollers"

at Accra in modern day Ghana, James Alexander (1835),

like Adams, also observed juvenile surfboard riding.

In a brief

account he wrote of "boys swimming into the sea, with light

boards under their stomachs.

They waited for

a surf (wave); and then came rolling in like a cloud on the

top of it."

In a

later conversation, he was told that the local

surfriders were occasionally threatened by sharks.

At Batanga

(Cameroon), Thomas J. Hutchinson

(1861) observed the local fisherman surfriding in their canoes

where the waves broke on an extensive reef.

Apparently, the

conditions on this day were unfavourable for serious fishing,

or particularly suited to canoe surfriding, or a combination

of both.

He writes of a

group of the four or six riders in small light-weight one-man

canoes.

Hutchinson

describes the paddle-out, take-off, steering with a trailing

paddle at speed, and the inconvenience of the wipe-out,

somewhat mitigated by their being "capital swimmers – indeed,

like the majority of the coastal negroes, they may be reckoned

amphibious.".

Sharks are an

occasional hazard; Hutchinson was told that, shortly before he

arrived, a fisherman died after losing a leg to "a prowling

shark.""

While there

are numerous accounts of (adult) West Africans riding waves in

canoes, in those instances they are invariably in pursuit of

their livelihood, either in transporting freight or

passengers, or in returning from fishing.

In this case,

the Batanga canoe riders are clearly riding the waves for

simple pleasure, and in this sense, as noted by Kevin Dawson(2009),

it

is "the only (account from West Africa) that describes adults

surfing (recreationally)."

In the second of two books of her

travels to West Africa, a photograph by Mary H. Kingsley (1899)

shows six Batanga men and their canoes, possibly identical to

those observed surfriding by Hutchinson forty years earlier..

Mary H. Kingsley: Batanga

Canoes, West Africa, c1899.

When visiting the coast of the

Batanga people, C. S. Smith

(1895) observed and detailed their very light cork wood single

canoes; going so far as to weigh one, at an impressive

twenty-seven pounds.

Too narrow to seat an ordinarily

sized person, a narrow "saddle" laid across the gunwales was

used as a seat, and with very light paddles, they "scud over the

roughest sea without danger and with almost incredible

velocity."

Paddling predominantly with left

hand, the right is occasionally used to bail, and one foot is

trailed as balance, and presumably to assist in manoeuvring

Thus, "when they would rest their

arms, one leg is thrown out on either side of the canoe, and it

is propelled almost as fast with their feet as with the

paddle.".

While employed to lay undersea

cables On a Surf-bound Coast (the title of his book),

Archer P. Crouch

(1887) had many experiences in landing and launching in

surf-boats and canoes.

However it is his rare account of

swimming in considerable sized surf and taking instruction in

the art of body surfing from his African assistant, Su, that is

remarkable

In his ethnographic study of the

Tshi-speaking peoples of the Gold Coast, Alfred Burdon Ellis (1887) wrote

that "every portion of the shore where the surf breaks unusually

heavily, or rocks cause the water to become broken, and ...

dangerous for canoes, has its local spirit."

Capt. T. C. Hincks: Surf-Boats comming of from Cape Coast Castle, (Gold Coast), 1910. Printed in Johnston, Harry Hamilton, Sir : Britain across the Seas: Africa ... the British Empire in Africa, 1910, page 288. Internet Archive https://archive.org/details/britainacrosssea00johnuoft |

|

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |