barbot : surf riding and canoes, west coast, africa, 1712

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

surfresearch.com.au

barbot : surf riding and canoes, west coast, africa, 1712 |

Surf Riding

Barbot's (edited)

report from the coast of West Africa in Letter 18 predates many similar

accounts by Europeans of surf riding in Polynesia:

"the young

have no other occupation than to play in the sea, thousands playing on

the large waves of the

surf on the coast,

carried on little boards, until the sea casts them ashore on the sand of

its beaches."

While he states that "they take (the boards) in order to teach themselves to swim," this would appear to be highly unlikely for all the participants and given "the large waves."

In Letter 20, Barbot

reduces the number of observed juvenile surf riders from "thousands" to

"several hundred," and repeats his claim that the boards are used to learn

to swim.

He notes here that

as well as "bits of boards," the swimmers also use"small bundles of rushes,

fasten'd under their stomachs."

It is unclear whether

the riders fasten the boards "under their stomachs" with their arms, or

whether some infants are actually bound to their craft by their mothers.

In 1645, Michael

Hemmersam reported that on the Gold Coast:

"In the second and

third year they tie the children to boards and throw them into the water,

and so they learn to swim.

Thus they are brought

up with little trouble."

- Hemmersam (1663) in Jones German Sources (1993), page109

As Hemmersam was

not a source for Barbot, this appears to confirm that infants, "in the

second or third year,'" were bound to boards, or possiby the potentionally

less-dangerous bundles of rushes, in their intial introduction to swimming.

However, the

practice was unlikely to be continued with older and more experienced children.

Cleary more than

a swimming lesson, and reminiscent of Joseph Banks description of surf

riding in Tahihi in 1769, Barbot writes that the natives "sporting together

among the rolling and breaking waves ... is a good diversion to the spectators."

- cf. Beaglehole, J. C.: The Endeavour Journal of Joseph Banks, 1768 - 1771 (1962), pages 258- 259

Apart from the obvious pleasure of surf-swimming, the ability to swim and the experience gained in controlling any craft in the surf zone was basic training for a career as a coastal fisherman.

Swimming

Barbot is also more specific in Letter 20 in decscribing the swimming technique of the natives of Mina, the best on "the coast in dexterity ", as using an over-arm (crawl) stroke, unlike the breast-stroke familiar to Europe:

"throwing one [arm]

after another forward, as if they were paddling, and not extending

their arms equally,

and striking with them both together, as Europeans do."

The Author

Of Protestant French

origin, Barbot served aboard Dutch-English? vessels engaged in trade, principally

slaves, on a triganular route, with Western Europe, the west coast of Africa,

and, crossing the Atlantic, South America and the Caribbean, defining each.apex.

He took three voyages

in 1678-1979, 1681-1682, and 1699-1700, and his son James Barbot, junior,

in 1700-1701

The Book

Although The Writtings

of Jean Barbot are somewhat complex in their compostion, they are an

enlightening insight into the coastal cultre of the west coast of Africa.

In 1685, Barbot

moved to England, where he prepared the first account of his voyages

in French, published in1688.

Before his death

in 1712, he prepared a second manuscript in English, updating and adding

substantial material, which was eventually published in 1732.

Both works have

a considerable amount of material taken from earlier publications, with

additional sources available for the second work, and some of the illustrations

are re-drawn.

The editors of the

1992 edition have made a masterful attempt to correlate the material, identify

derived material, and present it in a useable format, with extensive introductory

notes and copious detailed endnotes.

For those seeking

further information, the following extracts include the editors' the endnote

numbers in (brackets), and the page or folio references to the original

edition in [square brackets].

The endnotes are

usually not reproduced, the major exception being the notes, on canoes

and fishing, to Letter 20.

River Senegal

or Zenega, which acts as a boundary on the North between these peoples

and the kingdom of Genehoa, flows more than 200 leagues in a direct course

from East to West, counting from the falls at the point where it leaves

the Niger, near Cantozy, to its mouth at By-hourt.6 [. ..]7

There are those

who say that one of the branches of River Senegal, to be seen near the

sea on the coast to the North, makes its way into River St Juan, in Genehoa.(8)

River Senegal

is navigable [p. 21] for sloops up to 100 leagues beyond a place called

Le Rocher.

Several kinds

of fish are found in it, and also water. horses, crocodiles, and snakes

with small horns, for its waters have the quality of increasing the fertility

of animals.(9)

Page 39

The coast to the

North is all sand, with a few hills, some wide plains, and little vegetation.

The other side

of this river is.alm~~t all forest. Its islands are very pleasant ones,

and all are mhablted, especially one near the mouth called Islet St Louis

where the company known in France as the Compagnie du Senegal has established

its trading station.(10)

The waters of

this river leave it so impetuously that they run two leagues out to sea

before mingling with those of the ocean.

They can be seen

on the surface of the sea, and could be taken for breakers or a sandbank.

If carefully collected a league and a half from the coast, the water is

found to be still fresh, and many vessels obtain their water this way.

The rapidity

of River Senegal is due to the distance it travels between its source and

its mouth, and to the narrowness of its channel.

The entry to

the river is made very difficult by the speed of flow, the currents forming

the most danger- ous bar on the whole coast of Guinea and Nigritia.

The great quantity

of water carried in its channel, and the impetuous flow, have the effect

of bringing down the sand and sludge encountered en route.

Transported to

its mouth, they are stirred up by the NE winds prevailing in these parts

which keep the sea in motion at all levels, and hence push this detritus

back towards the land where it is heaped up and forms a cross bank.

This bank is

called 'the bar', because it effectively bars the entrance to the river,

but it is not always in the same place, being shifted further out or further

in, according to the relative strength of the currents and the winds.

The bar totally

prevents ,large vessels entering the river, and even the lighter~(barques)

which the Company keeps here for trading purposes, and which are called

barques

de barre since they are built expressly to negotiate the bar, have

great difficulty in entering.

At certain times

of year a fortnight can go by before the lighters dare pass the bar, and

this happens between December and March which, although spring, is nevertheless

the most troublesome period because of the heavy rains which have filled

River Niger during the wet season.

Those who regularly

cross the bar of River Senegal swear 'that the more often they do so, the

more dangerous and troublesome they find it.

The waves break

so violently and frequently, rising so high and making such a noise (especially

when there are sea mists, which is common at midday), that it is enough

to make even the most determined man tremble with fear.

The dangers of

this bar also cause frequent delays in the despatch of vessels.i(11)

However, if on

the one hand the Senegal Company is disadvantaged by the bar, on the

Page 40

other hand it provides greater security for the Company's Residence (l'Habitation) on Islet St Louis, which otherwise has only the protection of a few guns. (12)

Page 72

The sea teems

with fishes because the coasts of the maritime districts are thinly inhabited

and the few people who live there are lazy by nature, so that they go fishing

only when there is nothing to hunt on land.

They use little

boats hollowed out of a tree-trunk, in which they can go 3-4 leagues out

to sea to fish, either with lines or with fish-spears, and sometimes with

nets.

The Portuguese

call these little boats almadies. [p. 33 bis]

Page 76

Perpetual greenery

is to be seen in this district, for although trees lose their leaves, there

are so many kinds and the alternation is well ordered, that when one tree

is losing its foliage, others are regaining theirs.

This is why the

Ancients placed their alleged Elysian Fields in this clime, and why they

further persuaded themselves that the ocean which bathes these shores is

almost always tranquil and calm in summer, and that if it is heard roaring,

this is only on its edges, where it meets bars and shoals, which is apparently

why they gave it the name 'Pacific'.

The shores of

the ocean are carpeted with fine white sand like dust, which goes to show

the tranquillity of the ocean watering them.(31)

Page 100

I have told you

that these Nigritians are great hunters.

They usually

employ bows and arrows, and they shoot to kill.

Those of them

living along the coasts of Senegal, Cabo-Verde and Gambia hunt more intensively

than those in the interior, and individuals are more skilled at it.(30

As for fishing,

I have also told you, Sir, that they use lines, hooks, fish-spears and

nets.

The nets are

woven from twine made from tree-bark, and so are the lines.

With this tackle

they set out in the morning from rivers and bays, two or three of them

in each little canoe, the canoe being fitted with either two or four sails

(a few have six).

They sail out

two or three leagues and return when the wind changes near midday.

They catch many

of the sorts of fish I have already drawn for you, but especially one sort

of sardine which forms their chief food. Since they are too lazy to go

fishing often, they preserve a large number of these sardines in the sand

along the shore, claiming that the sand is as effective as salt.

After leaving

them there for several days, they expose them to the sun which dries them,

and they then make use of them as they need.

One can see whole

buildings full of them, and the shore at Rio- Fresca covered with these

sardines, while being 'salted' or drying. But since the sand is not a very

effective preservative, the extreme heat makes the fish go off, and they

give out a stench so strong as to be unbearable to anyone except these

people, especially at the height of a summer day.

The sight of

so many little fish [p. 46] half rotten

Page 101

and scattered

everywhere on the sands makes one quite queasy.

Apart from the

fishing done during the day, they fish at night by lorch-light, killing

the fish either by shooting arrows or with a spear. [margin: see vol. 2,

p. 82r]

Page 239, facing.

Page 239, facing, detail.

Page 275

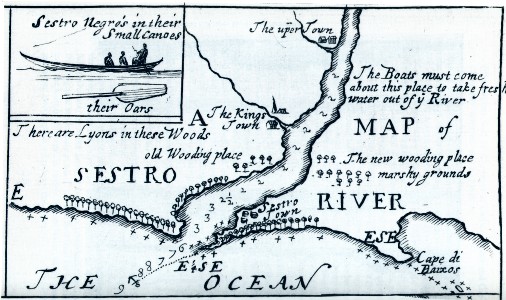

[pg 128/4-5, on

trade at Rio Sestro, and anchorage there]

Rio Sestro is

a place of trade for elephants teeth, rice and Guinea- pepper, and very

convenient for wooding and watering, and consequently much frequented by

all European nations that every year pass by, bound to the Gold coast,

Ardra, and the Bight or gulf of Guinea.

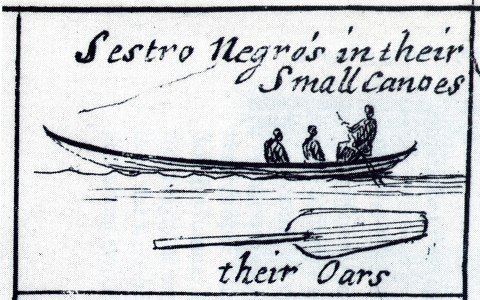

The Negroes of

Sestro commonly come out of the river in canoos to meet the ships they

spy to the westward, to shew them the roads, or bring them into the river.

/

The best place

for great ships to anchor, is in six or seven fathoms ouzy ground, somewhat

above half a league from the bar of the river, where there is a good hold,

if the ship be well moor'd; and 'tis much easier for the crew to carry

water and wood.

Whereas anchoring,

as most do, in eight or nine fathom, about a league from shore, is very

toilsome and hazardous, the ground being there all rocky and hard sand;

the anchors have no hold, and the cables very often, in few days, by the

continual motions of the waves, are either quite cut in the rocky grounds,

or at least much worn and shatter'd, unless the anchors be remov'd almost

every day; which is a 'very great fatigue, and many anchors have been broke

in working of them up.

[po 128/8, on

the welcome at Rio Sestro]

The access to

the beach and the landing are very convenient for

Page 276

boats and pinnaces.

There is a large

house in the village for the I reception of strangers, whither the captain

of the Blacks, one i Jacob, and his attendants, commonly conduct, and there

make them welcome, with palm-wine, and such other things as the country

affords.

It is, like all

the common houses, rais'd upon timber, and there is a small ladder to get

up into it.

These strangers

discourse the Blacks about the occasion that brings them; but nothing is

concluded before the king of the country is inform'd: and to this effect,

they are carried by water to his village, which is seated about a league

up a rivulet, near the mouth of the Sestro.

The Moors of Axim

are for the most part fishermen.

They make very

fine, large canoes for crossing bars and transporting merchandize. The

country is extremely fertile in maize, rice, coconuts, sweet and bitter

oranges, limes (limons), bananas, water melons, pineapples and many

other fruits and salad-plants. You also find there many sheep, cows, goats,

poultry and pigeons, with a large quantity of game.

The palm-wine

there is excellent, and the monkeys are very beautiful and entertaining.

(19)

Page 346

You find

here [at Tacorar], the finest and largest canoes in the whole of Guinea;

they are used for cossing the bars at Juda and Offra, and for transporting

their merchandise from one place to another.

They are made

from a hollowed-out tree-trunk, but have such large stowage space that

some can be seen carrying up to ten tons as well as the crew, which consists

of 18-20 oarsman.

Vessels destined

to buy slaves at Arda always equip themselves with one, either here or

at axim.

The Moors sell

them for £400-£600 in merchandise. (50)

Page 381

Page 400

It is very hard

to land at Manfrou, on account of the great breakers around the rocks in

front of the hill, at whose foot the village is situated.

The most favourable

place for landing is East of the fort.

It is best to

anchor one's longboat at a distance from the shore and wait for canoes

from the land.

The best roadstead

for vessels is North and South of the fort in 13-14 fathoms of water on

good holding ground.

The English dispute

this roadstead with the Danes and claim that it belongs to them, and that

the Danes do not really have any roadstead at all.(33)

...

The people of

Corso and Manfrou devote themselves more to fishing than to any other occupation.

But among them there are many merchants, who go into the interior and act

as brokers for the other Moors who live far from the sea.(35)

Page 416

Anomabo, Nomabo

or Janassia (all of these are names for the same place) is a large village,

just under one league from Cormentin and 2 1/2 leagues from Mouree.

It is divided

into two parts, one occupied by fishermen from Mina, the other by those

of Fantyn.(5)

It is difficult

to land there at certain times; but generally speaking, it is the best

landing place on the whole coast of Fantyn.

People often

beach their shallops on the sand in between the rocks, which form a kind

of large and spacious harbour.

The problem is

to get past these rocks, but this can be done if you take your time.(6)

The surrounding

country side is very pleasant, with a great variety of trees.

The best palm

wine of Gold Coast grows [sic] there, as well as the largest quantity of

maize.(7)

Page 455

Page 506

[Letter 18, Marrige ceremonies and bringing up children]

The whole of the

time when the young Moors are with their mothers is for them a time ofliberty,for

they have no other occupation than to play, to run about and to bathe in

the sea or the river.

I have seen thousands

of them together, playing on the large waves of the surf on the coast,

letting themselves be carried on little boards (which they take in order

to teach themselves to swim) and being almost like crabs for several moments,

until the sea casts them ashore on the sand of its beaches, whelt, from

a distance, they look like little monkeys.(20) [. ../p. 72/.. .](21)

[Footnote, page 510

] 21

20. In 1679 Barbot

noted his pleasure at seeing 'the thousand natural monkey-tricks' of African

children, and added that they had a lively spirit and good judgement, so

that anyone who instructed them would not be wasting his time (1679, p.

340).

The first two

sentences in this passage, including the reference to parents selling their

children, derive from Marees, f. 13 (for the alleged sale, see Marees 1987,

p. 26, note 1), and this also mentions swimming; while the description

of children at play, although largely original, was probably inspired by

Villault, pp. 237-8, who compared children seen from a distance, not with

monkeys, but with 'little devils'.

...

Cf. 1732, p.

243/3, which embroiders and adds, perhaps from recollection, that instead

of a board some children used 'bundles of rushes, made fast under their

stomach', but omits the reference to the children before and after the

age of from eight to ten.

Facing page 519

After that of

merchant, the trade of fisherman is the most [p. 79] esteemed and the commonest.

Fathers bring

their children up to it from the age of nine or ten.

Every morning

(except Tuesday, which is their Sunday), a very large number of fishermen

come out from the land for up to two leagues.

There are many

of them at Axim, Anta, Comendo, Mina, Corso, Mouree and Cormentin, but

more at Comendo and Mina than elsewhere.

Some days you

can see 300-400 at each place.

Their fleets

slowly movee out one and a half or two leagues with the light land-breeze

and on a calm sea, in order to reach the depth they need to fish, and then

they disperse, each canoe going its own way to fish without impeding any

other.

Normally each

canoe has two men, one standing up to fish, the other sitting at the extreme

rear, in order to steer it and direct it towards what they think are the

best places.

They always carry

in the canoe a cutlass, some bread and water, and live fire on a large

stone for cooking fish when they want a meal.

From this drawing

you can detect, Sir, the pleasure one gains in seeing so many fishermen

at work around a vessel at one time.

I applied myself

vigorously [to sketch them] in these few moments.

[illustration

no. (80), fishing canoes off the coast]I2t

They fish in the

morning, because this is the time when the fish bite best and also because

it is when the land-breeze keeps the sea calm and still.

And towards noon

they return with the sea-breeze, which increases by degrees and blows so

strongly that, if they waited till the evening, they would have great difficulty

and danger in reaching land, on account of the violent breakers.(13)

Constant practice

in fishing makes these Moors very expert in the art, so that they have

exact knowledge of the characteristics of each fish and the season of the

year to catch it.

They have several

ways of fishing, both by day and by night.

I shall detail

these for you.

By day, they

fish either with lines or with nets made of palm-fibre.

They attach hooks

Page 520

to the lines at

[p. 80] varying distances, according to the behaviour of the fish they

are proposing to catch. (14)

I have seen 20

hooks on some lines and five or six on others, while the normal number

is two.

Some fishermen

attach the lines to their head, ~ing them on each side of the head or on

one side only, in order to have their hands free to lift the fish aboard

and to detect more sensitively the fish biting.

You cannot but

admire the skill of these men at certain times, as when the fish are biting

heavily and they pull out five or six of them at once very rapidly.

Others hold lines

in their hands as the canoe drifts along, and others again make the hooks

jump along the surface of the water, in the way we fish for bonito. (15)

[.. .](16)

They fish also

for bonito, dolphin-fish, sucking-fish, large carangues with small eyes,

and a large fish resembling a shark but darker, which is why they call

it negros - its flesh is excellent.

Here are some

of these fish which I have sketched for you from nature, to satisfy your

curiosity.

[illustration

no. (81), four fish] 17 Ip. 81/t

Here also you

see by itself the sketch of a large fish I saw at Comendo, the Fetish Fish.

[illustration

no. (82), the Fetish Fish](18)

Apart from sea-fish,

they have many river-fish, but quite different ones from ours, there being

any similarity only in the carp and pike.

In rivers, nets

are used more frequently than lines.

These Moors are

so untiring in this work that they take very little rest, for after fishing

in the sea for part of the day they spend part of the night fishing in

the rivers, which is, however, less rewarding.

They set up their

net (tilet) on dry land, as we do.(19) [.. .](20)

But this way

of fishing [by standing in the water] is liable to lead to terrible disasters,

on account of the large number of those marine monsters, the sharks, who

cross the breakers and tear apart those who go out a little too far.

Yet these Africans

also wage destruction on the sharks, going out deliberately, in order to

take them with great harpoons or with lines, to reduce their numbers, and

because they sell them at a very good price to the Moors of the interior,

who like the flesh when sun-dried.

Should it happen

that they take a shark of extraordinary size, as many of the sharks in

fact are, they

Page 521

help each other to land it, and they distribute it among the people of the village, who eat it in a spirit of hatred.(21)

They also fish

among the rocks for various sorts of fish, with implements made for the

purpose and like those with which we take conger eels in Aunix.

There is one

particular kind of fish, called by the English 'King's Fish', which has

an excellent taste when cooked and served in butter.

They also gather

many mussels which are as good as those in England, and such large oysters

that two suffice for one man.

Since you want

to recognize everything as if you were touching it as well as seeing it,

I have drawn this plate which will enable you to envisage more clearly

what I have been describing to you about the various [p. 82] forms of fishing

from the land. I have forgotten to state that they also fish with cast-nets,

and some with scraps of cloth they hold in both hands, between two tides,

lifting them up when they see fish in them, but this method is only for

little fish.

The inland peoples

have different ways of fishing from those by the sea.

But I think there

is no need to say more about the fishermen.

Let us turn to

the goldsmiths.

[illustration

no. (83), ways of fishing [f2]

Page 528

Those who make canoes generally live at Axim, Ackuon, Boutrou,

Page 529

Tackarary and

Comendo, since these lands are forested.

They make them

from the trunk of a tree, using curved knives.

The canoes are

shaped like a coffer on the upper parts (encoffres par haul), and

flat below [on the floor], the two ends pointed so that they can be easily

carried on the shoulders when out of the water.

Next they hollow

out the trunk with great chisels and apply fire to those parts they cannot

tackle with their tools, and finally they smooth it, outside and in, with

other small tools, which takes them a long time.

However, they

make them very light and very neat.

The length of

the common canoes is 16-18 feet, and the width is 20 inches, but at Takorary

and Axim they make canoes 35-40 feet long, five feet wide and three feet

in depth, and in these they can easily carry 6-10 tons of merchandise as

well as a crew.

These are called

'cargo canoes', and the Moors use them to transport their cattle and merchandise

from one place to another, taking them over the breakers loaded as they

are.

This sort can

be found at Juda and Ardra, and at many places on Gold Coast.

Such canoes are

so safe that they travel from Gold Coast to all parts of the Gulf of Ethiopia,

and beyond that to Angola.

They are moved

by paddles or by sail, and travel rapidly on account of their lightness,

provided that their crew is reasonably powerful.

To tackle the

breakers, they have usually 10, 12, 16 or 18 men, according to their size

and cargo.

War-canoes carry

up to 60 men, with their weapons and foodstuffs for 15 days.43

The men rowing

canoes sit in twos, on benches set across, from the stern [forward].

Each man has

a paddle, or oar, this being a pole [p. 84] three feet long with a portion

of board attached at the end and shaped like the iron head of a pike.(44)

The man who steers

this kind of boat sits at the stern, with a paddle a little larger than

those of the others.

They hold the

paddle in both hands.

The men of Mina

are the best at manoeuvring these canoes over the breakers without an upset,

at least more often than not without one, and you could hardly manage with

any other men at Juda arid Offra, where the breakers are more dangerous

than anywhere else in Guinea.

And when it happens

that they have been upset in the surf, they are so expert that that they

lose little of what has been entrusted to them because it is attached to

the canoe, tied to the little bars which cross it at intervals, making

it like a sort of pontoon.

Most fishermen

have little poles in their canoes for the same purpose.

The speed with

which these people generally make these boats travel is beyond belief,

Sir. I am speaking especially of the small canoes, even though

Page 530

they have only

two or three rowers.

The rear is so

low that the sea] often washes in there, as well as over the sides which

are nearly at water level.

One man in the

canoe does nothing else but bale out with half a calabash.

I have very often

been obliged to travel in either the large canoes or the small ones, as

the demands of the trade required me, in order to go ashore, yet I was

never once upset.

Mind you, I had

some alarming moments, sometimes lasting a quarter of an hour, when we

were between two swells, waiting for the most suitable time to dash across

the breakers, which can only be done at great risk.

The rowers know

exactly the right moment, which is usually when three large swells have

passed by and when those men stationed on the neighbouring rocks shout

out to them to come in.

Then, Sir, they

drive straight at the land with such strength and determination that the

canoe appears in sight half-way through the breakers, just as a swell,

like a mountain of boiling water, coming from behind, begins to break.

This does not

prevent the canoe from receiving the spray, and sometimes it is even uplifted

to such a height that it seems as if it is being transported through the

air between two hillocks of water, and this hides it for several moments

from the view of those ashore causing great perturbation to those unaccustomed

to the sight.

In this state

you are thrown on the beach by the second swell, which carries the little

vessel well up, and on to dry land.

You then realise

the lightness of the canoes, Sir, for they are met by several Moors who

run into the water up to their buttocks, in order to unload the notables

or the goods aboard, to avoid their being further soaked, for often the

canoe, being without protection, fills with water after being beached,

its prow being up in the air and its stern low down.

All this is even

more difficult in the new and full moon [because of the high tides].(45)

So much for landing

in a canoe.

Now I am going

to describe for you how to leave for another gestination in a canoe.

You get into

the canoe on dry land and put the goods aboard the same way.

Then the little

vessel is pushed into the water by a host of men, who howl like wolves

as they hand it over to the crew, who leap in on both sides.

They keep the

canoe head on to the swell, and swim as far as they can, breasting the

breakers.

The swell lifts

the canoe practically on end, and then lets it drop with a crash, which

is terrifying and which scares anyone who has not experienced this before.

All goes well

if the canoe remains head on to the swell, but if it begins to twist or

Page 531

fails to rise,

then it will certainly be overwhelmed by a mountain of water, which often

costs the life of those who encounter it and cannot swim sufficiently,

or who are torn apart by the sharks.

Fortunately one

can trust implicitly in the blacks on these occasions, for they take particular

care to save everyone.(46) [p. 85]

The sails of

these canoes are mostly made of reed mats or [woven out] of plant roots,

and their rigging is of palm-fibre twine.

They paint their

canoes various colours and garnish them with fetishes, behind and before,

to keep them safe, as some people do with guardian angels.

Most of their

fetishes are ears of millet, and the skulls and muzzles of lions and tigers

or the dried heads of goats, monkeys or various other animals.

Those canoes

making long voyages are adorned with a dead goat hung aloft in honour of

the (47)(48) feush. ...

Additional Passages from 1732

[po 266/7, on

crossing the surf]

When the bar

canoos, or any other [canoes of] smaller sizes, are to stand in for the

land through the breaking waters, the crew

narrowly observes

to have the three high surges, which usually follow one upon the back of

another, pass over, before they enter upon beating waters.

The Blacks, who

at those times always wait on the beach, either to succour the canoos coming

in, if any accident befals them, or to unlade them as soon as they are

safely arriv'd on the strand, give a shout from the shore, which is a signal

to those in the canoo, that the three great surges are over; which they

can better judge of from the land, as being higher above the water.

Then the canoo-men

all together, with wonderful concert, paddle amain, and give the canoo

such swift way through the beating [? breaking] water, which foams and

roars in dreadful manner on both sides, that it is got half way through

before the succeeding surges, which commonly rise and swell prodigious

high the nearer they come to the beating, can overtake it: and thus the

canoo holding that rapid course in the midst of the foaming waves, runs

itself at once almost dry on the sandy beach; many of those Blacks, who

continually attend there for that purpose, running into the water up to

the knees, or middle, before it has touched the ground, and take out the

passengers on both sides, whom they carry ashore, though often very wet

with the waves breaking into

Page 532

the canoo.

After that they

also take out the goods, and carry where commanded.(49)

[p. 267/2, on

rowing canoes and swimming]

I have often

admir'd the dexterity of the fishermen, when some of them happened to come

ashore later than is usual, in the afternoon, at which time the sea-breeze

makes the sea swell considerably near the land: I observed how two or three

men, in so small, so low, so narrow, and so light a boat, in which he who

sits at the stern to steer seems to have his posteriors in the water, could

so swiftly carry the canoo through the breaking sea, without any misfortune,

and with little or no concern; but this must proceed from their being brought

up, both men and women, from their infancy, to swim like fishes; and that,

with the constant exercise, renders them so dexterous at it, that tho'

the canoo be overturn'd, or split in pieces, they can either turn it up

again in the first case, or swim ashore in the second, tho' never so distant

from it.

The Blacks of

Mina out-do all others at the coast in dexterity of swimming, throwing

one [arm] after another forward, as if thev were paddling, and not extending

their arms equally, and striking with them both together, as Europeans

do.

There, as I have

hinted before, may be seen several hundred of boys and girls sporting together

before the beach, and in many places among the rolling and breaking waves,

learning to swim, on bits of boards, or small bundles of rushes, fasten'd

under their stomachs, which is a good diversion to the spectators. so

[p. 267/3-4, on

Europeans landing and European pleasure-boats]

I would advise

those, who are to go ashore, to send their best clothes before them, in

a trunk; for I have often spoil'd good apparel upon such occasions, and

especially when the Blacks lift a man out of the canoo just when it reaches

the beach, as has been said before: for they being always anointed all

over with grease, or palm-oil, certainly leave the impression of it on

his clothes, where. soever they touch them, and it is scarce ever to be

got out.

There every European

of any note, commonly wears fine silk, or woollen suits, and often adorned

with gold, or silver galoons; according to the post he is in, each studying

to exceed another; besides that the Blacks, as well as other nations, show

most respect to those who are best dressed.

Page 533

There is another

sort of very fine canoos, of ' about five or six ton burden, which every

commander of an European fort keeps for a pleasure-boat, to pass with his

attendants, as occasion offers, from one place to another.

The Danish general

in my time had the finest of that sort.

In the midst

of it was a large auning, of very good red and blue stuffs, with gold and

silver fringes, and under it hand- some seats, covered with Turkey carpets,

and curious curtains to draw on iron rods.

At each end of

the auning was a staff, bearing a little streamer, and another at the head

of the canoo, and under it the Danish flag. These canoos are represented

in the cut of the prospect of fort Fredericksburg, at Manfrou near Corso;

where is also another canoo, which was for the Danish general's servants

and soldiers, which usually attended his own canoo.

In the cuts of

the castle of St George of Mina, cape Corso castle, and Christiaenburg

at Acra, are exact draughts of the great canoos, used by the English and

Dutch to carry goods and passengers along the coast; to which prints I

refer, as to the form of the canoos, and the manner of fitting and rigging

them.(51)

[po 268/6, on

the small canoe]

This sort of

little canoo is exactly represented in its proper form and shape in the

print, showing five or six hundred of them abroad fishing, at Mina; and

just under it is the other sort of canoo, carrying slaves aboard the ship,

both of them differing much from the bar canoos, and those made to perform

voyages.

The latter is

exactly drawn in all its parts, to give the reader a just idea of it, and

the way of rowing and steering, and therefore it will be [f.52] needless

to say more of It.

Page 543

43. In 1679 Barbot

had learned that Takoradi was a centre for canoe- making, especially for

the canoes purchased by European ships, and he observed, at sea, large

canoes with sails, used, he suggested, by the Dutch to convey goods to

Ardra and Benin, and carrying up to eight tons (1679, pp. 286, 289, 304).

In the present

passage the method of canoe-making (clumsily described), and what follows,

apart from the references to Juda and Ardra, are from Marees, f. 59v, and

Dapper, p. 101/4-103/2, with some embroidery.

(Note that the

crew of a large canoe must be an odd number of individuals, to allow for

a steersman.)

For drawings

of these canoes, see note

544

51. below; and

for other references to them, see Letter 2/3, p. 7 and note 51, above;

Letter 3/20, p. 228, below.

For the historical

use of canoes in West Africa, see Smith 1970.

I.Cf. 1732, pp.

266/1-3, 6, 268/2-4, which enlarges helpfully.

The sizes of

f canoes are different (from 40' x 6/ to 14' X 3-4/), perhaps representing

a . compromise with Bosman, p. 129; the canoes are made from Capot trees,

which are 'very porous and soft' (the name of the tree from Bosman, p.

295); the sides are 'somewhat rounded, so that it is somewhat narrower

just at the top, and bellies out a little lower, that they may carry the

more sail: the head and stern are raised long, and somewhat hooked, very

sharp at the end'.

44. Inaccurate or badly worded, paddles being formed in one piece.

45. The description

of canoes being rowed echoes Marees, f. 58v, but like the rest may be from

personal observation.

In his 1679 journal

Barbot included a useful bird's-eye view of a large canoe, and drawings

of a paddle and of a stool used as a seat in canoes (confirming Marees,

f. 58v); and he recorded that the rowers sat towards the stern and that

seats were placed at ..

intervals forward,

'in order to sail more conveniently without getting wet'.

Further, he noted

that overturned canoes were quickly righted, and that goods were saved,

because in small canoes they were lodged under a slatted 'deck' (pont

Ii barreaux).

He was warned

about the dangerous breakers at Ardra, and he noted that, at Kormentin,

pinnaces could not land and instead use had to be made of 'nasty little

canoes which can hardly carry two men', but he did not refer to specific

incidents (1679, pp. 304, 312, 319, 345-6).

It was stated

in 1671 that certain canoes built on the Ivory Coast were no use as 'bar

canoes' because they had rounded bottoms (Delbee 1671, p. 370).

Cf. 1732, pp.

266/4-5, 7, 267/1, which clarifies, enlarges or changes several points.

The rowers sit

on 'benches, or boards nail'd athwart the canoo', the paddles are shaped

'like a spade, about three feet long, with a small round handle about the

same length' (perhaps from Bosman, p. 129), the rowers 'being excellent

swimmers and divers' recover goods from upset canoes (the obscure reference

to fishermen and poles may also relate to recovery of goods).

Barbot observes

that the danger is greater in the months of April to July, as well as at

high tides, and especially so at Fida and Ardra, where 'dismal accidents

are very frequent, and great quantities of goods are lost, and many men

drown'd; whereas at the Gold Coast those things happen but seldom, tho'

they use smaller canoos, the landing being nothing near so bad as at those

other places.

I have gone several

times ashore at the Gold Coast, both in great and small canoos, without

any ill accident, by reason of the good management of the paddlers, who

were all chosen men, and because it was always at the best seasons: yet

I must own, that sometimes I escaped narrowly, and wish'd my self elsewhere,

being in a small canoo, for a quarter of an hour, or better, waiting between

two dreadful waves, and

Page 545

rolling surges,

for a proper minute to launch thro' the breaking sea, before Cormentin,

which is generally the most dangerous landing-place of all the Gold Coast;

in such a manner that it almost made my hair stand up on end with horror.

At another place,

I think it was Mouree, I ventured to go ashore in the pinnace, and landed

pretty well; but the worst was to get off again: to which purpose I hir'd

several Blacks, who, with my own men, all swimming with one hand, kept

the head of the pinnace right against the rolling waves, but could not

prevent my being thoroughly wet.'

The description

of crossing the surf, being somewhat clearer in 1732, is given in the Additional

Passage.

For an earlier

reference to the canoe-men at Mina, see 1732, p. 157/1 -an Additional Passage

to Letter 2/5 above.

46. Cf.1732, p.

266/8.

This is better

put and makes it clear that the rowers jump into the canoe after swimming

with it.

47. Based on Marees,

f. 59v, Dapper, p. 103/2, and Villault, p. 325, but slightly enlarged,

perhaps from observation, Barbot adding the rigging an4 the animal heads.

Cf. 1732, pp.

267/4, 268/1, which adds that 'the European canoes have commonly European

canvas and cordage'.

48. Omission of

three sentences, on canoe-making at Agitaki, and on the terms ekern,

almadia,

and 'canoe', from Marees, f. 58v.

Cf.1732, p. 268/5,

which adds that the word 'canoo' comes from the West Indies.

49. The term 'bar canoos' was introduced by Barbot in 1732, p. 266/5, for the canoes crossing the surf at Fida and Ardra, barre being the term employed in 1688 for the breakers or surf on open beaches, as well as for the breakers marking the 'bar' of rivers.

50. Based on Marees,

ff. 59, 93v-94v, Villault, pp. 237-8, and Dapper, p. 97/6.

Note that while

contemporary Europeans swam breast-stroke, some Mricans swam an over-arm

stroke, perhaps a form of the crawl. For a contemporary account of children

learning to swim, see Jones 1983a, p. 109.

The last sentence

repeats a description in 1732, p. 243/3.

51. The 'pleasure-boat'

first appeared on the drawing of Fort Christiansborg (1679, p. 333), but

was later transferred to the drawing of Fort Frederiksborg (illustration

no. (63): in Letter 2/6, p. 25, above; cf. 1732, Plate 14 (p. 177) -the

second canoe being added).

The 'great canoos',

sometimes with one or two sails raised, are on drawings of Mina castle

(illustration no. (61), in Letter 2/5, p. 17, above; cf. 1732, Plate 8

(p. 156)); of Cape Coast castle (1679, p. 303; cf. 1732, Plate 10 (p. 169),

labelled C, 'A large Canoe of abt. 12 Tuns'; but not illustration no. (62),

in Letter 2/6, p. 25, above); of Fort Christiansborg (1732, Plate 15 (p.

182), twice, but not on the previous versions (1679, p. 333, and illustration

no. (70), in Letter 2/10, p. 37, above); and of Cape Ruygehoeck (illustration

no. (67), in Letter 2/8,

Page 545

p. 32, above;

cf. 1732, Plate IS (p. 182)).

Small canoes

and European boats appear on most seascape illustrations, the latter being

difficult to distinguish, when in the distance, from large canoes.

52. The reference

is to the two illustrations in 1732, Plate 9 (p. 156).

The 'exactly

drawn' canoe is in fact copied from Marees, plate 8.

Page 722

[Letter 11: Island of Fernando Poo and the island of the Prince (Principe), Gulf of Ethiopia]

The countryside

lying behind and around the town is all hilly and wooded, thus drawing

to it the rain and storms very common here.

Clouds often

cover the hills, and thunder-storms are so frequent and so drastic that

they make one tremble, since the caves and chasms echo the noise and make

it terrifying.

You might think

that all this inclement weather would make the air impure and unhealthy,

yet this is the locality within the Gulf where a sick man recovers most

rapidly, and indeed where those from S. Tome and the other islands are

brought in order to recuperate most successfully.(9)

The land is very

fertile and produces in abundance oranges, lemons, bananas, coconuts, sugar-cane

-sugar itself being made here (albeit a very dark kind), rice, manioc,

some vine plants, very many cabbages, salad-plants, vegetables of all kinds,

pawpaws, good tobacco (better than that of Brazil), maize, millet, cotton

(from which they make various goods), melons and pumpkins.

They roast the

bananas when green and eat them instead of bread.

The flour from

manioc they call farinha de pau or 'wood flour'. The forests

Page 723

contain large

numbers of the flower we call belle de nuit.(10)

The Portuguese

inhabitants grow these products on their plantations in the hills.

They have slaves

to work the land.

They also rear

many kinds of animals -pigs, sheep, goats and the largest hens in Guinea.

They sell all

these provisions to the Europeans who come there for refreshment and to

careen their vessels. (11)

Every ship pays

40 pieces-of-eight, either in cash or in merchandise, in duties to the

Governor, in return for permission to water, collect wood and anchor.(12)

The best place

for watering is in the bay itself, where various torrents fall headlong

into it from the hills around about.

The water is

excellent -yet very dangerous if too much is drunk without letting it stand

for some days, as several ships have experienced, mainly in relation to

the slaves.

Firewood can

be obtained anywhere you wish, for the forests come down to the sea, and

the wood is very easy to cut.

Sometimes scorpions

are encountered [p. 181] whose sting can cause nasty consequences.

One of my crew

was stung there (on my latter voyage), but fortunately there happened to

be present a Moorish slave who seized the animal and crushed it over the

wound, which was already beginning to swell up greatly.

The man was cured

before nightfall. (13)

The bay is also

very rich in fish, the same kinds being caught there as in Guinea.

There are many

fish of the kind called 'Coffres de Mort' because they have flat underbellies

and a sharp edge on their back, with two little horns.

Here is a drawing

of some of these fish.(14)

I[illustrations no. (101), two fish, Orfie and Le Coffre de Mort] (15)

The sea around

this island and particularly in this bay nourishes an enormous number of

sharks which are extremely dangerous, since some of them are so extraordinarily

large that they can swallow half a human body.

I say this, having

seen it with "my own eyes.(16)

Page 732

[Notes: Letter 11]

16. In 1679 Barbot

noted sharks in the bay and witnessed them seizing bodies of dead slaves

thrown overboard, in one instance cutting the body of a youth in two (1679,

pp. 349-51).

Cf. 1732, p.

402/6, where the shark makes 'but one mouthful of a young boy'.

However, earlier

Barbot had remarked that 'when we threw a dead slave into the sea, particularly

about the mouth of the bay of Prince's Island in the gulph of Guinea one

shark would bite off a leg, and another an arm, whilst others sunk down

with the body; and all this was done in less than two minutes; they dividing

the whole corps among them so nicely, that the least particle of it was

not to be seen, not even of the bowels' (1732, p. 225/8- but some elements

in this passage are copied word for word from Bosman, p. 282).

Page 753

[Letter 17: Fishes of the Saharan coast]

Dolphin-fish and

sharks are caught in a different way, the former with a fish-gig or harpoon,

the latter with a shark-hook, a heavy iron fish-hook, baited with a large

piece of pork fat.

I will not go

into details about these creatures, since they are well known. I shall

simply say that the dolphin-fish is the most beautiful fish in the sea,

so that the sailors call it 'the dauphin of the sea' and further that it

has been given the name' dorado' [gilded] on account of the beauty of its

skin, which seen in the water appears a pleasing mixture of silver, gold

and blue.

Its flesh is

good eating.

As for the shark,

you will know, Sir, that this monster of the deep is very dangerous.

It tears to shreds

anything it comes up against.

But I will say

more about this in another place.

Page 772

[Letter 20: Altrnate course from Europe to the Gold Coast]

This route from

Cap de Lopo to Cayenne will take you 40-45 days, and you will have a good

wind, smooth seas and very few severe storms, apart from some squalls near

Cape Lopez and Annoboan and some heavy showers off America, with very occasionally

some water-spouts, otherwise known as 'dragons' tails'.

As soon as you

see one of the latter, take the precaution of furling the sails in time.

Do not be stubborn

on these occasions, for this has led to many serious disasters.

You can tell

these storms are coming, either by night or day, when you see a small black

cloud shooting up on the horizon which in no time covers the whole hemisphere.(12)

During such an

easy passage, there is pleasure to be had in fishing and taking sea-creatures,

for apart from often catching bonitos, tunny, porpoises, sharks, dorados,

flying fish and sucker-fish, you can often see thousands of whales and

grampuses, which appeal by their slow and heavy movements.

You can take

many of the birds which the Dutch call Meuvettes and the French

Fous

[Fools], be. cause they let themselves be handled and so seized, when they

perch on the yards and rigging in the evening to spend the night resting,

which happens especially in the vicinity of the islands of St Matieu

Page 773

and Ascencion.

Almost all of

them come from the latter island.

There are [p.

232] two or three sorts.

Some are as big

as a young goose, with a large long beak and short legs shaped like those

of a duck, and their cry is piercing. Here is what they look like.

[illustration no. (115), the Madcap bird]

Others are white

and smaller, with red feet, and others again are small and very like lapwings.

These creatures

are found in great flocks on these seas, where they live on flying fish.

I have sometimes

had whole hours of diversion watching these birds prey like vultures on

millions of flying fish, which the bonitos and tunny have forced to take

to the air, out of their own element and into that of the birds, in order

to save themselves.

But as if the

winged creatures were in collusion with the bonitos, both being enemies

of these wretched amphibians, the birds force ttte flying fish to return

to to the sea so that they become the prey of those they try to flee from,

or else in flight they become the prey of the Fools and other birds that

frequent these seas.

However, this

whole confused scene is diverting to watch.

Since I know

you like plenty of illustrations, I present you with a drawing I made on

the spot, which I am sure you will find ..(13) very mterestmg.

Page 717

[Letter 10]: Description of Rio Gabon, and of the lands from there to Cap de Lopo Gonsalvez at the equator.]

Sir, today I am

to tell you about Rio Gabon and the lands between it and Cabo de Lopo Gonsalvez,

where Guinea ends, and where I will conclude my description. [.../pp. 173-176/...](1)

Cape Lopo is

almost always uninhabited, having only 18-20 small huts for those residents

of Olibatta who come there when there are any ships in the bay, in order

to sell them the water and wood they need.

They also bring

a little wax and ivory, which they trade for knives (bosmans), bars

of iron, and sheets, also a few other trifles.

The wood is all

cut into two-foot billets and a sloop can be filled for one iron bar.

You usa pay to

the Chavepongo of the village a small due for anchorage and for water.

The water is

obtained in a large muddy marsh near the point of the cape.

The water keeps

well at sea and is better than that obtained on Isle du Prince and much

better than that obtained on St Thome.(2) [.. ./pp, 177-178/.. .](3)

|

Barbot on Guinea The Writtings of Jean Barbot on West Africa 1678-1712. Originally published in 1688 and 1732. Two volumes Edited by F. E. Hair, Adam Jones, and Robin Law The Harklut Society, London, 1992. |

|

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |