de marees : swimming, canoes, and fishing, guinea, 1602

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

surfresearch.com.au

de marees : swimming, canoes, and fishing, guinea, 1602 |

Swimming

In chapter 42, Pieter

de Marees describes those living in the coastal towns of the Guinea as

excellent swimmers, "easily outdoing people of our nation in swimming and

diving" and where the young, "girls as well as boys," swim daily.

The women also swim

very well, in the "same manner as the Men," however, "they are not able

to dive or stay under water for a long time."

He recounts one

instance of a native woman swimming after her companions, who had dived

overboard from his ship moored in the roads, following a dispute over ownership,

and they all reached the shore together.

Although that it

unlikely that de Marees explored any of the hinterland, he reports that

these aquatic skills are not shared by those living inland.

Unsuprisingly, the

West Africans are accutely aware.that sharks are a serious danger to limb

and life.

They are able to

dive to considerable depths for long periods, and, according to de Marees,

they are employed in West Indies to dive for pearls and to retrieve fresh

water from below the saltwater layer off the coast of India.

In a somewhat confused

passage, he notes:

"They swim in the

manner of the Portuguese, that is with their arms above the water,

one forward and

one backward, and similarly with legs, like Frogs."

This confusion is

evident in the editors' comment that the "description suggests that the

'Portuguese style of swimming' was the crawl; yet this is in fact less

'frog-like' than the breast stroke, with which people are traditionally

taught to swim in Holland."

Critically, a combination

of the over-arm (crawl) stroke and the breast stroke frog-kick would be.grossly

inefficient, nothwithstanding that it is probably impossible to coordinate.

While the breast

stroke was, of course, not unknown, several contemporary accounts confirm

that the natives of West Africa swam with the crawl style, that is, alternate

strokes by the arms combined with alternate strokes of the legs.

As such, de Marees

appears to be suggesting that, at least some, Portuguese swam in the crawl

style; commonly said to be unknown in Europe at this time.

As trading on the

coast of West Coast of Africa by the Portuguese dated from the 1460s, it

is possible that, by 1600, some visiting Portuguese sailors had seen and

adopted the native crawl style.

Canoes

Fishing

The Author

The Book

First published

in Amsterdam in Dutch in 1602, it was followed by a French translation

(Amsterdam,1605), and an English edition, published by Purchas in

1624.

In addition, German

and Latin translations, poorly transcribed and heavily edited, were published

by de Bry brothers of Frankfurt am Main in 1603-1604.

The editors of the

1987 edition have made a masterful attempt to correlate the material, identify

derived material, and present it in a useable

format, with extensive

introductory notes and copious detailed endnotes.

For those seeking

further information, the following extracts include the editors' the endnote

numbers in (brackets), and the page or folio

references to the

original edition in [square brackets].

In some seasons

many Fish are caught there, such as Stonebream, Lobsters, Cod (or what

looks rather like it) and very many other kinds of Fish which we did not

know and could not name.

They use there

very fine fishing gear, such as Harpoons made of iron, with which they

shoot the Fish, as well as equally fine nets which they out of Tree-Bark,

knotted like a Purse [5a] all with wide Mesh.

Thee nets are

round, closed at the bottom and open at the top.

They let them

sink to the sea-bed with a stone which drags them down to the bottom.

They tie the

bait in the middle, and when the Fish comes to suck it, they perceive this

at once.

Feeling that

it has come to take a bite of the bait, they pull the net so that the top

is closed, like a pouch.

They also use

Canoes which they cut out of a tree; in these they paddling them as on

the Gold Coast; but the Spoons or Paddles with which they paddle are different,

being round at the bottom end, like a Table-top; they are made in a very

slovenly manner.

Page 15

They [the people

of the Grain Coast] are very good Farmers, sowing a lot of Grain, in which

they do considerable trade.

They are also

very skilled in many crafts, especially in making fine Canoes or little

Boats with which they go out to Sea; they make them out of a hollow tree,

like a Venetian gondola, and for travelling they are verycrank.(8)

[Footnote] 8.

synde

seer ranck om mede te varen.

The adjective

ranck

is used to describe a vessel that is liable to capsize.

European travellers

were fascinated by the canoes of the Grain Coast, which were much smaller

and more fragile than those of the Gold Coast: cf. Liibelfing in Jones,

German Sources, 11 and n. 5.

Page 26

Once the children

begin to walk by themselves, they soon go to the water in order to learn

how to swim and to walk in the water.

...

When the children

have thus spent their youth in roughness ana reach the age of 8, 10 or

12, the Parents begin to admonish them [13b] to do something and

set their hands to some kind of work.

Fathers teach

their sons to spin yarn from the bark of trees and to make nets; and once

they know how to make Nets, they go with their Fathers to the sea to Fish.

Knowing now a little how to row or paddle, they set out to fish with only

two or three Boys in a Canoe or Almadia,(4) and what they catch they bring

to their Parents to be eaten.

But when they

[Footnote] 4.

Portuguese almadia, 'vessel', from Arabic al-ma'diya, 'raft'.

The term was

widely used by Europeans in West Africa in the seventeenth century to describe

African canoes.

Page 27

are about 18 or

20 Years old, the Sons begin to do their own trade and, taking leave of

their Father, go to live with two or three other Boys together in a house.

They buy or hire

a Canoe (one of their little Boats) and set out to Sea to fish together.

Having caught

something, they sell it for Gold, first setting aside [enough] for their

own needs and then buying from what is left a fathom of Linen, which they

wrap around their bodies [and] between their legs, thus covering their

male parts, as they begin to acquire a sense of decency.

In addition,

they begin to trade with the Merchants and to take them with their Canoes

to the ships, serving the Merchants as Rowers.

Thus they begin

to get into the Gold trade and to earn something.

Page 28

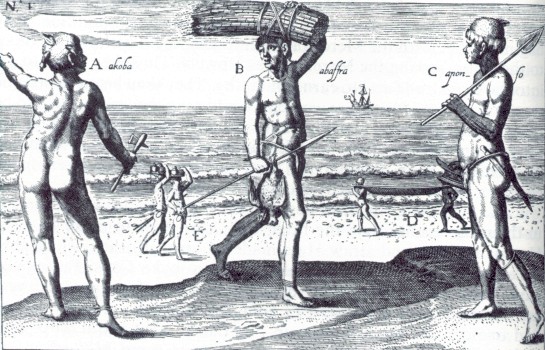

Description of

Plate No. 1

This picture

shows what the Men are like [and] of what stature and form they are.

Letter A shows

a slave, whom they call Akoba,(a) in the manner they go to the field

with their axe [cutlass], which they call Coddon,(b) in order to

cut wood.

B. shows the

young farmers called Abaffra,(c) come with their sugar-cane and

other fruits to the market.

C. shows a Fisherman

or Pilot, called Aponso,(d) how they go with their gear, such as

the little wooden Stool on which they sit and an oar with which they paddle,

going to the beach to set out.

D. shows how

two Blacks carry a canoe on the beach to bring it into the water.

E. shows how

the Housemen come to the Markd with Palm Wine.(e)

[Footnotes]

a. Probably akoa

paa, 'domestic slave'.

b. Coddon = k?d?(w), 'machette, cutlass' (lit. 'go weed'), not the primitive kind of axe shown in the engraving.

e Ab?fra simply

means 'child, young person'.

The term for

a farmer is akuafo.

d. A misprint

for aponfo, 'fisherman' (lit. 'one of the sea people').

De Marees' use

of the tenn 'pilots' is interesting.

Canoe men (remadores)

played an essential role in communication between ships and the shore:

without their services trade would have been virtually impossible, as there

are no real natural harbours on the Lower Guinea Coast.

It seems, however,

that these fishermen never became full-time remadores.

Cf Ch. 9.

e. Huysluyden is the plural of Huysman, which strictly means 'freeman, common farmer'.

Page 32

They are also expert Swimmers and divers, and are better in this than our nation.

Page 116

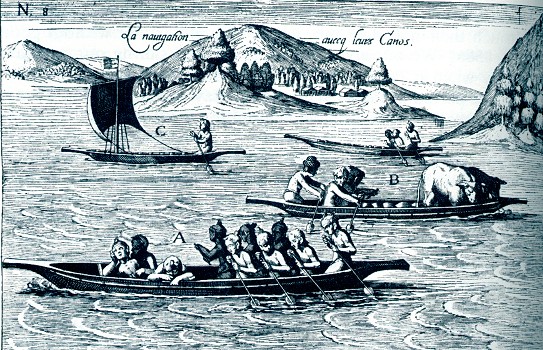

Description of

Plate No.8

The picture shows

how and in what manner they navigate on the sea with their little Barges

(which they call in Portuguese Almadia and in their language Cano or Ehem)

and [58b] do their trade; they are made out of a single Tree.

A. shows

in what manner they bring the Merchants on board the Ships in their Canoe.

B. shows

their cargo Barges with which they bring all provisions to the Castle de

Mina and sail up and down.

They are the

Slaves of the Portuguese.(a)

C. shows

a Canoe with a sail made of Tree-bark, sailing along the coast to sell

Palm-wine: it is called Lovis dobre.(b)

[Footnotes]

a. De Marees'

statement that rimadores (canoe-rowers) were slaves of the Portuguese

is probably incorrect.

These rimadores

played an important role in the coastal trade and formeda powerful pressure-group:

a strike on their part could paralyse trade completely.

The Portuguese

even used the Elmina rimadores, generally fishermen, for a form

of indirect colonisation, encouraging them to settle in little colonies

all along the Guinea coast.

Thus a Dutch

map of 1629 shows 'Mynsche visschers' (Elmina fishermen) at various

places.

Later the Dutch

adopted the same policy: in the early years of their settlement on the

Slave Coast, for instance, the English complained bitterly about the Elmina

rimadores

in that area who, clamining that they were Dutch subjects, refused to co-operate

and even threatened the lives of Cape Coast rimadora whom the English tried

to employ.

b. Lovis dobre:

it is unclear what term De Marees can have meant.

Page 117

The Barges with

which they sail on the sea and of which they make use in their Towns (1)

are cut out of one Tree.

They call such

a barge Ehem; by the Portuguese it is called Almadie and by us Dutch Cano.

These Canoes

are made and cut out of a Tree, without any pieces being jointed into them.

They are made

after a fashion different from the langados which are used in Brazil and

S. Thome and also from the Phragios in the East Indies.(2)

Although it is

a slight vessel in the water, it is nonetheless very good to sail fast

with; it is a rather low Instrument,(3) which does not rise high out of

the water, and the steersman often sits in the stern with his body in the

water.(4)

They are able

to sail very well with them and develop a great speed, as if they were

small Frigates.

They are long,

low and narrow: people can only sit one abreast, and at least seven or

eight, one behinq another, sitting on round little stool- made of wood,(5)

half of their bodies emerging above board.

In their hands

they hold an Oar like a Spade, made of a certain kind of hard wood.

They know how

to paddle with these Oars simultaneously, in the manner of a Galley, and

the Steersman keeps [the vessel] straight.

They can paddle

so fast that it appears [59a] as if they fly through the water, and one

could not keep up with them rowing in a Sloop.

If the waves

are high, they do not make such progress, as the heaving of the rollers

takes away their speed; yet in quiet water there are no Frigates, Sloops

or Gondolas which could keep up with them.

Even if only

one man sits in it, he can control it and sail on the Sea with it.

They know how

to adjust their bodies to the pitch of the Canoe and prevent it from. capsizing.

Since we Netherlanders

are not as experienced in this as they are, If we want to sail in them,

not being able to adjust ourselves as well and steer them properly, the

result is that the Canoes capsize immediately and we fall into the water.

There

[Footnotes]

1. end in

hunne Steden mede behelpen: lit., 'and with which they help themselves

[make do] in f their Towns'.

Perhaps De Marees

meant 'which they use to sail from one town to another'.

Alternatively

the phrase could mean 'The barges. .[or] what they use in their stead'

(in de stede van = instead of).

2. Fante (e)h?n,

'canoe'; Portuguese almadia, 'canoe'; Portuguese lanchlio,

'barge, lighter'.

Phragios

probably represents the Malay word perahu, describing a type of

sailing boat with out-riggers, known in English as proa.

3. een leegachtig

Instrument could also be translated 'an emptyish [? = hollow] vessel'.

The word leeg

normally

means 'empty', but in the Flemish dialect it can also take the place of

laag,

'iow'.

4. dickmael

dat den Piloot achIer met zijn lichaem int water sidt.

It is not clear

what this means.

If the rowers

really sat inside the canoes, rather than on benches linking the two sides

(as they do today), it is likely that not only the steersman but all the

rowers were sitting in the spray-water which entered the boat, especially

when crossing the surf.

It is more probable,

however, that the steersman sat well above the water-level, as suggested

in Plate 8.

5. siltende

op ronde stoeltkens van haul ghemaekt.

To fit the shape

of the canoe, such stools would probably have to have been rounded at the

bottom.

Perhaps, however,

what De Marees took to be stools were in fact floats for fishing nets.

Elsewhere he

stated that the rowers sat on a stone (see Ch. 12, n. 3).

Page 118

are some who do know how to manage and steer them, but they very few in number.

They [the canoes]

are very frail and capsize easily; and even though it does occasionally

happen that a canoe capsizes with some Negroes on the high Seas, they manage

(whilst they are in the water) to turn it over, scoop the water out, jump

back into their Canoe and sail on with it, without taking it ashore.

They venture

to sail with them not less than four or five miles out to Sea.

But as they find

it difficult to control them in rough water, they use them mainly in the

early morning to do their business, some to go out fishing, others to take

Merchants to the Ships to trade.

By the time the

breeze comes at noon, when they have done their business, they again make

for the Shore.

They [the canoes]

are generally 16 foot long and one and a half or two foot wide.

They also have

others which they use for warfare or for taking Oxen from other places,

and these are bigger: I have seen one,

as mentioned

above, which was as big as a Sloop; one could use it to do great violence

if one were to put two pieces of Stone-ordnance (6) in the snout [bow]

of this Barge using these [guns] at will, and also erect a Mast with a

Yard and sail.

It was 35 foot

long, 5 foot wide and three foot high; the rear was flat, with a Rudder

and benches, the whole made and cut out of one trunk.

Many of these

are made at Capo de Trespunctas, as enormously thick and tall Trees grow

there, not less than 16, 17 or 18 fathoms in circumference. [59b]

These Canoes

are much used by the Portuguese to sail from one Castle to another and

fetch provisions.

Yet the Negroes

have some too, which they use with sails made of rushes or Mats made of

straw, having learnt to do so from the Portuguese; but the biggest ones

they make are for the needs of the Portuguese.

Many other small

ones are made in Anta, because much timber grows there which is good for

the making of Canoes, and the inhabitants occupy themselves with making

them and selling them to strangers or their Neighbours; they cost here

the value of four Angels of Gold or one Peso, which is nearly seven Guilders

Dutch money.

There are small

ones in multitude, especially at a place called Agitaki (alias Aldea de

Torto), where in one day they sail out to Sea for fishing, seventy or eighty

at a time.

When they come back from the Sea and have done their things with them, they do not let them lie in the water, but take them at once and drag them on to the beach; then they come [together] at each end, and lift it [the vessel] on to four Trestles (7) (specially made for that purpose)

[Footnotes]

6. Steenstucken:

small naval ordnance used for shooting stone balls.

De Marees's suggestion

somewhat impracticable: it would be very difficu!t to place even a single

gun with its carnage In the prow of a canoe.

It would be equally

difficult to cross the surf with a canoe containing an ox, although on

the lagoons of the Volta delta (which De Marees apparently not visit) large

canoes can indeed carry very heavy loads.

7. ende draghen

die op vier Micken.

From De Marees'

description, it is obvious that canoes were much smaller than those used

nowadays, and a canoe 16 foot long and I i foot wide could [continued

on page 119] indeed be carried by two strong men.

But why four

trestles would be needed to support such a small vessel is hard to

explain.

Today canoes

are too heavy to put on trestles and are simply hauled up the beach to

a point which the tide cannot reach.

Because of their

rounded keel, only a small part of the vessel is in direct contact with

the beach, so that it can easily dry and there is little dander of it rotting,

especially as most canoes are used virtually every day.

Page 119

to let it dry, in order that it may not rot and may be lighter to use and row, two men can take it on their shoulders and carry it in-Land.(8)

They are first

hewn in an oblong form with machetes which are brought to them by the Dutch.

The upper part

of the sides are made a little narrower, and flat under the bottom; then

the upper part [is made] open; both ends, front and back, taper narrowly

like a hand-bow; so that the front and rear ends are made in virtually

the same fashion and there is little difference in them, except that the

front end is a little lower.

At both ends

they make a bow like the Cutwater or bowsprit of a Ship,(9)one foot long

and as thick as the Palm of a hand, which they use to carry the Canoes

to and fro.

They hollow it

[the canoe] out with an iron [chisel] of the kind used by makers of Bailers.(10)

They make the

sides only one finger thick, and the bottom two; when they have finished

hollowing [the canoe] out they fire it all

around with straw,

to prevent it from being eaten by the Worms and by the Sun.

They support

the boards or sides with props, so [60a] that they will not shrink but

become even and smooth.

Furthermore, they

do not forget to drape them [their canoes] with some Fetisso or Sanctos:

they often paint and colour them with Fetisso and drape them with ears

of Millie and Corn, so that the Fetisso may protect them well and not let

them die of hunger.

Thus make their

Canoes and little Barges quite pretty and artistic.

They also

maintain them well and take them together to a fixed place where they let

them dry; each man takes his own [canoe] when he wants to go out sailing

and fishing.

[Footnotes, continued

from page 118]]

8. te Landewaerts

inne here probably means 'up the beach': it is difficult to imagine

why anyone should carry a canoe from the seashore to the interior.

9. een bough

als ern Gallioen of penne van een Schip.

The cutwater

(galjoen) was a triangularpiece of wood attached to the bow of a

ship, designed to divide the water before it reached the bow.

It was generally

ornamented and ended in the figurehead, which was surmounted by the pen

(bowsprit).

The comparison

of the simple extension of the bow of a canoe (cf. Plates 9a and 9b) with

these elaborate structures is intended to be humorous.

10. Gietemakers:

a gieter is normally a watering-can (from gieten, 'to pour'),

but here 'bailer'

seems a more

appropriate translation.

Page 120

Description of the first Plate No.9 [= 9a]

[Footnotes]

a. Quorgofado

represents the Portuguese word corcovado, 'haunched, curved, bent'.

Cf. Ch. 29 n.8.

b. so worpen

sy het want naer den Visch ende hem so int liif.

As a nautical

term, want means 'rigging'; hence it can also mean a vertical fishing

net.

But the expression

ende

trecken hem so int liif and the fishing gear shown in the engraving

suggest that want in this case signifies not a net but a line with

hooks.

There was a special

kind of net known as a hoekwant (? a fishing net provided with hooks),

used by the type of fishing vessel called a hooker (hoeker).

Page121

Description of

the other Plate 9 [=9b]

[60b] B.

This [man] has a burning Torch in his hand; in the other hand he has a

Harpoon, and when he sees a Fish swimming, he spears it with the Harpoon;

the

steersman merely

steers and paddles towards the Fish which he sees swimming.

A. These

[men] have holes in their Canoe and a little wood-fire in their small boat,

whose rays shine into the sea through the holes; the Fish come to see this,

taking pleasure in the rays, upon which they are speared with a Harpoon

by the Negroes and caught.

C. This

man is fishing with a cast-Net of nearly the same fashion as ours.

D. These

people are catching Fish with Baskets, having in one hand a basket made

like a Hen-Coop, and in the other a Torch; if they see some Fish swimming,

they throw these Baskets over them and take them out of the top, stringing

them with a skewer on a string, which they gird around their bodies.

This is an excellent

Fish, (in taste) not very different from Salmon.

The greatest diligence

and valour they show in fishing, because youth they are trained and educated

in it.

They fish t the

week, throughout the week except on Tuesdays, which is the Sabbath they

celebrate, when they do not go out to fish. At different times of the year

they use different types of Gear to catch different kinds of Fish.

They use many

kinds of Implements and catch many kinds of Fish too, as will be explained

below.

Often they fish

at night and make Devices like Torches, which they keep burning in one

hand, having other a Harpoon: they stand erect in the Canoe, while the

steersman sits in the stern and steers or paddles; the Fish is attracted

by the fire and is then caught by spearing it with the Harpoon.

These Torches

are made of light, dry wood which they cut into chips, coat Oil and then

bind together like a torch; they are about six foot long and about as thick

as an arm, and burn excellently.

Others

Page 123

Page 125

[Footnote]10.

Joseph de Acosta, Historia natural y moral de las lndias (Seville,

1590) Lib. III, Cap. 17.

DeMarees must

have read the translation by Jan Huygen van Linschoten (1598).

Page 186

As it is customary

for children, from their earliest youth onwards, to spend their time in

the water every day, girls as well as boys, without any distinction or

bashfulness, the Inhabitants here, especially those [94a] living

in the coastal towns, are very good Swimmers.

But the Peasants

of the Interior are completely inexpert; indeed, they are frightened when

they see water or the sea.

Earlier I mentioned

how clever they are in turning over their Canoes (when they have capsized

in the water) and drying them out again [bailing out the water] and it

is therefore not necessary to tell that story again.

I shall merely

describe briefly in what manner they manage to swim.

They are very

fast swimmers and can keep themselves under water for a long time.

They can dIve

amazIngly far, no less deep, and can see under water.

Because they are

so good at swimming and diving, they are specially kept for that purpose

in many CountrIes and employed in this capacity where there is a need for

them, such as on the Island of St. Margaret in the West Indies, where Pearls

are found and brought up from the bottom [sea-bed] by DIvers, as is more

elaborately told in the Histories written about that subject.910

In the East Indies

too, in places such as Goa and Ormus, where they dive no less than 20 fathoms

deep into the salt water in order to bring up from below it fresh water

which the people drink because it is free of certain diseases and Worms,

they often use Negroes or blacks for this purpose on account of their great

expertise in swimming and diving.

Yet no matter

how experienced they are, the Negroes here are not very happy about going

into the water, and that is because of their fear of certain Fish called

Rekiens

in French, Tubaron in Portuguese and Haey in Dutch.(2)

This kind of

Fish is their great Enemy; when they are in the water and swim, the Fishes

swim towards them and bite their legs off, or, what is worse, swim on with

the man, dragging him down and eating him up.

They swim in the manner of the Portuguese, that is with their arms above the water, one forward and one backward, and similarly with

[Footnotes]

1. Acosta, Histaria

natural, IV, Ch. 15.

Here and in the

following sentence, de Marees is sidetracked from his topic, the Gold Coast,

where there is little opportunity for diving, although many people are

expert swimmers.

2. Today sharks

rarely come close to the coast of Ghana, although seventeenth century sources

suggest that this has not always been the case.

The barracuda,

which is more common near the coast, can attack human beings as well as

large fish.

Cf. Ch. 33.

Page 187

[Footnote] 3.

This description suggests that the 'Portuguese style of swimming' was the

crawl; yet this is in fact less 'frog-like' than the breast stroke, with

which people are traditionally taught to swim in Holland.

|

Description and Historical Account of the Gold Kingdom of Guinea (1602) Originally published in Amsterdam, 1602 Translated from the Dutch and edited by Albert van Dantzig and Adam Jones. Oxford University Press, 1987. |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |