|

surfresearch.com.au

polynesian surfriding : tahiti to 1900 |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

Contents

| u3.1

Samuel Wallis, 1767.

u3.2 Louis de Bougainville, 1768. u3.3 Joseph Banks, 1769. u3.4 Banks' Surfcraft, 1769. u3.5 William Anderson, 1777. u3.6 The Bounty at Matavai Bay, 1788. u3.7 Surfriding Conditions, 1788. u3.8 James Morrison, 1788. u3.9 Royal Tahitian Surfriding, 1788. u3.10 William Bligh, 1788. u3.11 George Tobin, 1792. |

u3.12

James Wilson, 1798.

u3.13 Rev. William Ellis, 1822. u3.14 J. A. Moerenhout, 1834. u3.15 G. F. Gordon-Cummings, 1886. u3.16 Henry Adams, 1891. u3.17 Tueria Henry, 1928. u3.18 Ben Finney, 1956. u3.18 Tahitian Surfboard Construction. uEndnotes uAppendix A: Maps. uAppendix B: Weather Reports. |

Overview

The eariest European

explorers of the Pacific Ocean noted the maritime and aquatic skills of

the Polynesians.

Joseph Banks, a

member of James Cook's first Pacific expedition, reported surfriding on

the west coast of Tahiti in 1769.

This was ten years

before Cook's visits to the Hawaiian Islands in 1778 and 1779 on his third

and final Pacific vovage.

While the exact

design and construction of the Tahitian surfcraft in his report is unclear,

the activity was undoubtedly surfriding.

The most detailed

report of ancient Polynesian surfriding is by James Morrison at Matavai

Bay, Tahiti, in 1788.

Boatswain's mate

on the Bounty, despatched to Tahiti under the command of William

Bligh, Morrison was one of the mutineers and he eventually stayed nearly

two years in the Society Islands.

His journal is a

substantial record of native culture and his account of surfriding, read

in conjunction with Bligh's log, dramatically indicates the extreme surf

conditions favoured by Tahitian surfriders.

Calculations based

on Bligh's charts indicate these waves were in the range of 10 to 20 feet,

still considered a serious challenge by modern surfriders.

Anticipating later

Hawaiian accounts, Morrison notes surfriding was practised in large numbers

by all ages and classes and that some surfers rode in a standing position.

His report on the

expert surfriding skills of the Tahitian chiefs identifies the first named

surfrider, Iddeah, the wife of a local chief Ottu (or Tu) and a woman of

impressive talents.

The Rev. William

Ellis wrote of surfriding on Huhaine, an island to the north of Tahiti,

circa 1820 and in the Hawaiian islands in 1823.

Although he reports

Tahitain surfriding and surfboards as inferior to Hawaii, there are significant

similarities and in locating the surfriding on the reefs outside of Fare

Harbour, Ellis' account indicates that ancient surfriders rode transversely

across the wave face closely following the peel of the curl in the manner

of modern riders.

While some commentators

have insisted the ancients essentially rode straight towards the beach,

to do so at these locations could invite serious injury.

Only one report partially

details the dimensions and design features of Tahitian surfboards (Wilson,

1798) and there are no accounts of surfboard construction.

However the early

journalists provide extensive commentary on native carpentry, particular

in relation to canoe buiding.

Analysis of these

reports suggest that surfboards were probably shaped from a billet - a

seasoned section of timber split from a log; a process in marked contrast

with the widely quoted account of Hawaiian surfboard construction by Thomas

Thrum in 1896.

Furthermore, the

accounts of Banks and Bligh invite speculation as to the possible adaptation

of damaged canoes and paddles in the formative era of ancient surfboard

construction.

3.1

Samuel Wallis, 1767.

The island of Tahiti

was discovered (1) by the English explorer,

Samuel Wallis, in command of the Dolphin on 18th June 1767.

Arriving on the

east coast, Wallis was unable to locate a suitable anchorage due to the

large swell preventing safe entry to the inside of the reef:

"The (long) boats continued sounding till noon, when they returned with an account that the ground was very clear; that it was at the depth of five fathom, within a quarter of a mile of the shore, but that there was a very great surf where we had seen the (drinking) water." (2, 3)

Despite conditions that threatened the safety of the Dolphin, the ship's officers in the long boats reported that the Tahitians negotiated the surf without difficultly:

"The officers

told me, that the inhabitants swarmed upon the beach, and that

many of them

swam off to the boat with fruit, and bamboos filled with water." (4)

The Dolphin

was securely anchored on the north coast at Matavai Bay and while contact

with the Tahitians was initially confrontational, relations subsequently

improved and the expedition was able to trade for much needed provisions

during a stay of five weeks.

This was followed

by a further visit of two weeks on the neighbouring island of Moorea.

Wallis wrote extensively

of the construction of Tahitian canoes, by implication noting advanced

maritime skills. (5)

His notes on Tahitian

canoe construction are discussed below, see 3.14.

The successful landing,

identifying Tahiti as a suitable southern hemishere location to observe

the transit of Venus in 1769, was the precedent for the expedition of James

Cook.

3.2

Louis de Bougainville, 1768

Two French ships,

Etoile and Boudeuse, under the command of Louis de Bougainville

arrived on the east coast of Tahiti at Hitia'a on 4th April 1768

While the visit

was less than two weeks (they departed 15th April), in Europe the accounts

of the crew, largely focused on Tahitian sexuality, were cited as evidence

in support of the theory of "the noble savage", propounded by the

French philosophers Voltaire and Jean Jacques Rousseau.

French author, Nolwenn Roussel (2005) writes of a brief description of surfriding on Tahiti, attributed to Bougainville himself:

" ... des 1768, Louis Antoine de Bougainville, Francais et commandant la fregate du roi 'La Boudeuse', a rapporte dans ses notes que les insulaires « etaient capables de chevaucher la crete des vagues en se tenant debout sur des planches ».

... in 1768,

Louis Antoine de Bougainville, the French commander of the royal frigate

'Boudeuse',

reports in

his notes that the islanders 'were able to ride the crest of waves

while standing up on boards'." (6)

Unfortunately, the

quotation cleary has a wider context, is not annotated and the source is

yet to be identified.

Initial research

suggests that, amoung various cultural observations, the French journalists

did report on the sailing and swimming skills of the Tahitians. (7)

3.3

Joseph Banks, 1769.

The Endeavour,

commanded

by Lt. James Cook, arrived at Tahiti on 13 April 1769 to prepare

for observations of the transit of Venus, the visit lasting for two months.

The success of Cook's

expedition was substaintally enhanced by the inclusion of a group of scientists

and artists led and funded by Joseph Banks.

An immense amount

of natural and cultural information was collected, including an early written

account of Polynesian surfriding by Joseph Banks.

(8)

"Cook's journals are the starting point for all studies of the history and culture of four major island groups in Polynesia (Society, Tonga, New Zealand and Hawai'i) and of eastern Australia, Vanuatu (New Hebrides) and New Caledonia." (9)

While the anthroloplogical

evidence connecting Tahiti and the Hawaiian Islands is subject to often

conflicting interpretations, most agree regular contact had ceased by the

end of the thirteenth century. (10)

The early European

reports appear to accurately represent, to the best of the journalists'

understanding, the independent developments of several hundred years of

ancient Tahitian surfriding.

See Chapter 1 (in

preparation).

Joseph Banks, in

company with Lt. Cook and Dr. Solander, left the

Endeavour's

anchorage

at Matavai Bay on the 28th May 1769 and travelled to the west coast, initially

by boat and then on foot, where they stayed overnight. (11)

The following morning

on their return to Matavai Bay, Banks reported in his journal:

"In our return

to the boat we saw the Indians amuse or excersise themselves in a manner

truly surprizing.

It was in

a place where the shore was not guarded by a reef as is usualy the case,

consequently a

high surf

fell upon the shore, a more dreadfull one I have not often seen: no European

boat could

have landed

in it and I think no Europaean who had by any means got into could possibly

have

saved his

life, as the shore was coverd with pebbles and large stones." (12)

Banks is impressed

by the potential danger of surfriding, specifically notes the location

as adjacent to a break in the reef allowing the swell to reach the shore

(13)

and

indicates the wave size as

"high".

Given the extensive

nautical experience of Cook, and the intensive crash-course of Banks and

Solander in crossing the Southern Ocean, the wave height was probably considerable.

He continues:

"In the midst

of these breakers 10 or 12 Indians were swimming who whenever a surf broke

near

them divd

under it with infinite ease, rising up on the other side; but their chief

amusement was

carried on

by the stern of an old canoe, with this before them they swam out as far

as the

outermost

breach, then one or two would get into it and opposing the blunt end to

the breaking wave were hurried in with incredible swiftness.

Sometimes

they were carried almost ashore but generaly the wave broke over them before

they were

half way,

in which case the (they) divd and quickly rose on the other

side with the canoe in their

hands, which

was towd (originally swam) out again and the

same method repeated.

We stood admiring

this very wonderfull scene for full half an hour, in which time no one

of the actors

atempted to

come ashore but all seemd most highly entertaind with their strange diversion."

(14)

Initally identifying

a dozen bodysurfers, diving under the waves, Banks focuses on the

activities of those using " the stern of an old canoe", hereafter

refered to as the surfriders.

The nature of the

Tahitian surfcraft is at the core Banks' report and, while

apparently specific, invites further analysis given the significance of

a first report.

See 3.4,

below.

Banks' report of

the Tahitian surfriders' performance details four of the basic elements

of surfriding: the paddle-out, the take-off, the ride-in and the pull-out.

(15)

The performance

appears relatively sophisticated; the take-off at "the outermost breach"

is

probably on the green wave face and not merely in the white-water,

maximizing the potential wave size and length of the ride.

Riding on the green

face is further indicated: while some rides went all the way to the shore,

"generaly

the wave broke over them before they were half way".

Banks' phrase "with

incredible swiftness" may indicate an element of riding transversely

across the wave, the rider apparently travelling faster than the wave speed.

When the wave "broke

over them' the ride was terminated ("the pull-out") by the rider diving

down and forcing the board under the water to emerge behind the wave and

paddle back out.

"generaly the wave broke over them before they were half way, in which case the (they) divd and quickly rose on the other side with the canoe in their hands, which was towd (originally swam) out again and the same method repeated." (16)

The manouvre could

be described as an "island pull-out".

While breaking surf

often appears extremely violent to the uninitiated observer, the greatest

danger to the experienced surfrider occurs as a result of a collision with

a solid object; either the bottom of the seashore, their board or another

rider's board.

Control of the board,

particularly at the termination of the ride, enhances the safety of all

surfriders. (17)

Banks' appreciation of this "truly surprizing (and) strange diversion" features in most subsequent accounts.

3.4

Banks' Surfcraft

Analysis of Joseph

Banks' description of the Tahitian surfcraft as "the stern of an old

canoe" (and later in the text simply as "the canoe"), from an

experienced surfriders' perspective, is intuitively problematic.

Taking the description

at face value, it is unclear how the apparent bulk of a canoe stern, even

riden with extremes of strength and skill, could achieve the surfriding

performance suggested by Banks.

There is a possibility

that the description is misleading and close examination of the text demonstrates

some incongruencies.

This is not questioned

by J. C. Beaglehole who, perhaps understandably, simply paraphrases Banks

(18);

The first, and crucial,

difficulty is that as "no one of the actors atempted to come ashore",

it

is unclear how closely Banks was able to examine the craft or, at this

stage, his intimate knowledge of Tahitian canoes.

The surfriding narrative

appears six weeks into the visit, long enough to have some familiarity

with the culture and language but well short of the knowledge detailed

in Bank's comprehensive notes on Tahitian canoes compliled

ten weeks later as the Endeavour sailed south from the Society Islands.

(19)

One possible explanation

is suggested, below.

Secondly, the implied

dimensions are confusing.

While apparently

large enough to support two riders, the craft is small enough that the

riders "divd and quickly rose on the other side (of the wave)

with the canoe in their hands".

Only the shape of

one end of the craft is indicated: "opposing the blunt end to

the breaking wave".

However, by implication,

this suggests the (unreported) inverse: "the pointed end was directed

shore-ward".

J. C. Beagleholes'

1974 edition has Banks noting "the canoe ... was towd out again".

While perhaps consistent

with the impression of a "stern of an old canoe" , this is likely

an inefficient method of negotiating the surf zone and would require considerable

physical strength.

In the original

manuscript Banks initially wrote that the craft was

"swam" out,

but later crossed out the word and adjusted the text to "towd".

(20)

The consideration of an alternative term may indicate Bank's difficulty in describing the paddling process

Lasty, in examing

the text of the surfriding narrative, while the phrase "one or two would

get into it " (my emphasis) appears to imply the concave shape

associated with a canoe, it could be interpreted to mean "caught by the

wave/s".

Note that Banks

has previously used the term "into" to indicate such a meaning:

"no Europaean who had by any means got into (the high surf) could possibly have saved his life" (21)

An examination of

the descriptions and illustrations of contemporary Tahitian canoes further

complicates an understanding of Banks' description.

Wallis reported

in 1767:

"The boats or canoes of these people, are of three different sorts." (22)

The three designs

were the all-purpose single log canoe with outrigger, a large double canoe

suitable for inter-island voyages and a large double canoe with a covered

superstructure for royal or ceremonial use.

The first two were

paddled and, depending on size, also had sails, but the later was only

ever employed paddlers.

According to function,

there were significantly different stern features.

The largest of the

double-hull design was the fighting canoe with extremely elongated sterns

up to 18 feet above the waterline. (23)

The extreme sterns

of these craft, often elaborately decorated with carvings and banners denoting

rank or status, are beauifully illustrated by William Hodges in

"War

Galleys at Tahiti, circa 1774", one of a series of composite

works painted after Cooks' second visit.

(24)

The stern was less pronounced on the more common sailing, and the rarer ceremonial, canoes:

"their Sterns

only are raisd and those not above 4 or 5 feet; their heads are quite flat

and have a

flat board projecting forwards beyond them about 4 feet." (25)

According to Banks, the raised stern greatly assisted in negotiating the surf zone:

"The only thing in which they excell is landing in a surf, for by reason of their great lengh and high sterns they would land dry in a surf when our boats could scarcely land at all, and in the same manner put off from the shore as I have often experienc'd." (26)

As Banks notes:

"The form of these Canoes is better to be expressd by a drawing than by any description." (27)

There are a numerous

works by visiting European artists illustrating the various designs of

Tahitian canoes, including one drawing annotated in Banks' hand. (28)

A large ceremonial

canoe was illustrated by one of the two artists aboard the Endeavour,

H.D. Sporing:

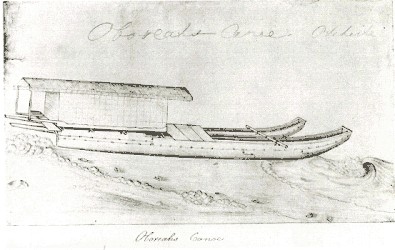

|

British Museum Add. MS 23921-23a (29) Purea, an elderly

queen of Tahiti,

|

Alternatively, if

the surfriding craft was simply one section or panel split from "the

stern of an old canoe", then it is difficult to comprehend how Banks

was able to provide such an apparently definitive description.

One possible senario,

alluded to previously, is that the description was suggested to Banks in

conversation with a Tahitian observer or commentator, subject to inaccuracies

in translation.

Cook's policy of

establishing cordial relations for trade and avoiding potential violent

conflicts with the native inhabitants of the Pacific depended upon effective

communication.

After anchoring

at Matavai Bay, by the end of the first week :

"The gentlemen began to study the Tahitian language." (30)

For the crew of the Endeavour, some basic language difficulties were probaly overcome by consultation with those marineers who had visited Tahiti previously with Wallis in 1767. (31)

No subsequent account

yet identified describes the use of damaged canoes for surfriding.

Although not detailed

in any of the available literature, the recycling of damaged canoes into

smaller craft may have been practised in the formative era of ancient surfboard

construction.

Before proceeding,

further consideration should be directed to Sporing's illustration reproduced

above.

Note that if, for

any reason, Banks' description refered not to the stern, but to the bow

(stem or head) of a Tahitain canoe as described and illustrated above,

then the surfcraft was undoubtedly a surfboard.

Thirty years later,

missionary James Wilson would use exactly such a description:

" a small board ... like the fore part of a canoe" (32)

| Also note the wave

study in the lower right of the drawing, detailed right.

This is a near photograhic representation of the dynamics a breaking wave - in surfriding parlance: "a hollow left-hander". (33) It features the thick

base, thin curl, effervescent white-water, smooth surface (possibly resulting

from a light off-shore wind) and, critically, the conical structure of

the wave face that is integral to the dynamics of transverse wave riding.

|

|

3.5

William Anderson, 1777.

On Cook's third

Pacific voyage, before arriving in Hawaii, a report of canoe surfing in

the Society Islands was recorded by William Anderson, surgeon on the 'Resolution'

(35),

in August-September 1777.

"He went out

from the shore till he was near the place where the swell begins to take

its rise; and,

watching its

first motion very attentively, paddled before it with great quickness,

till (it) had

acquired sufficient

force to carry his canoe before it without passing underneath.

He sat motionless,

and was carried along at the same swift rate as the wave, till it landed

him on

the beach.

Then he started

out ... and went in search of another swell.

I could not

help concluding that this man felt the most supreme pleasure while his

was driven so fast

and smoothly

by the sea." (36)

The canoe was, almost

certainly, fitted with an outrigger and the performance shares the basic

surfriding elements identified by Banks.

The take-off is

finely calculated by the rider on the outer-most break and ridden

"till it landed him on the beach."

The Tahitian canoe

surfrider probably rode directly to the beach, at least "as the same

swift rate as the wave."

Anderson's evaluation

of the rider's amusement as "the most supreme pleasure"

is, arguably, not an exaggeration.

3.6

The Bounty in Tahiti, 1788-1789.

Another member of

Cook's crew to visit Tahiti in 1777, and subsequently Hawaii in 1778-1779,

was then mid-shipman, William Bligh.

Bligh returned in

to Tahiti on 26th October 1788 as captain of the Bounty on

an unsuccessful mission to collect and transport breadfruit plants to the

West Indies.

The mission was

terminated by the infamous mutiny led by Fletcher Christian in 1789, precipitating

Bligh's epic 3600 mile voyage in an open boat. (37)

" 'Bounty'

was the first British ship to spend the summer's rainy season in Tahiti.

The season

still brings hurricanes and even today small ships prefer not to

be exposed

in the Pacific." (38)

At Matavai Bay, the

first anchorage in Tahiti, the Bounty was subjected to extreme swell

events that threatened the safety of the ship.

For a tabulated

record of the swell and weather conditions discussed henceforth, see

Appendix

B: Weather Reports: Matavai Bay and Toaroah Harbour, Tahiti.

On Thursday 6th November, one week after arrival, Bligh's journal records the first indication that his anchorage is exposed to northern swells (Swell #1):

"Much Swell setting into the Bay." (39)

The swell apparently continued for several days and on Sunday 9th the Bounty's log notes:

"... less Swell than Yesterday, but still much surf on the shore" (40)

A larger second swell (#2) arrived two weeks later, on Monday 24th November Bligh's journal reports:

"A very great

swell has set into the Bay, from which I have been expecting the Wind from

the

Westward,

but I now find it is owing to a N.N .E. Wind that has been blowing at Sea."

(41)

On Thursday 4th December, eight days later, the swell (#3) was again on the rise (42) and the log for the following two days notes:

"Much swell

setting in and the Sea at times breaking on the Dolphin Bank.

The Ship rolling

very much and a heavy Surf on all parts of the Shore." (43)

and, more dramatically:

"I experienced

a scene of to day of Wind and Weather which I never supposed could have

been met with in this place.

By Sun set

a very high breaking Sea ran across the Dolphin Bank, and before seven

O'Clock (7 am) it made such way into the Bay that we rode

with much difficulty and hazard.

Towards Midnight

it increased still more, and we rode untill eight in the Morning in the

midst of a

heavy broken

sea which frequently came over us.

The Wind at

times dying away was a great evil to us for the Ship from the tremendous

Sea that broke

over the Reefs

to the Eastward of Point Venus, producing such an outset thwarting us against

the

Surge from

the bank which broke over us in such a Manner, that it was necessary to

batten every part of the Ship.

In this state

we remained the whole Night with all hands up in the midst of torrents

of Rain, the Ship

sending and

rolling in a most tremendous manner, and the Sea foaming all round us so

as to threaten

instant destruction.

" (44)

By Wednesday 10th December, this swell had abated:

"In the Morning very little Swell in the Bay." (45)

Continuing the roughly bi-weekly pattern, the swell rose again (#4) and on Saturday 20th December, Bligh reported:

"A very heavy

Swell in the Bay and a great sea on the Dolphin Bank

& much

Surf on the shore, Ship rolling very deep." (46)

The journal of James Morrison, boatswain's mate on the Bounty, confirms Bligh's report and indicates the difficulties this presented the crew.

"On the 20th

(December)

we

had heavy rains & a strong Gale of Wind from the N W which brought

with it a heavy sea from that Quarter breaking so violently on the Dolphin

Bank that the Surge run fairly over the Ship, and the Carpenter who was

the evening before Confined to his Cabbin, was now released to secure the

Hatches.

Several things

were washd overboard & had not the Cables been very good the ship must

have gone on shore.

Next day the

Gale abated, but the surf run very high on the shore so as to prevent landing

either in Canoes or Boats." (47)

These events encouraged Bligh to seek an alternative anchorage.for the Bounty.

"as the

Weather was become unsettled and so much Sea

run into the

Bay, ... it was unsafe for the Ship to ride here" (48)

On the 24th December

he relocated the ship south-west of Matavai Bay to Toaroah Harbour for

the remainer of his stay.

While riding safe

at Toaroah Bay, the northern swells were still in evidence and the log

records another increase in swell (Thursday 8th January, #5).

Towards the end

of the month there was a further week of extreme surf (#6), 22nd to 28th

January :

"A very heavy Sea breaking allover Matavai Bay and as much on the Reefs here." (49)

and, five days later:

The northern swells

made one more appearance before Bounty's departure on the 5th April

1789.

On Monday 2nd March,

Bligh reports:

"The Wind blowing

Strong from the N. W.

I sent a Man

down to Taowne Harbour (t) to see if the Sea set much in, it being open

to that quarter.

He returned

with an Account that a great Sea broke all over it and that it would have

been bad riding

there for

any Ship, and that a Great surf run on the Shore.

Matavai is

equally bad, but here we lye as smooth as in a Mill-pond." (51)

On 8th March, seven days later, this swell (#7) is still very much in evidence:

"A High Sea running over the Dolphin Bank into Matavai Bay." (52)

After relocating the Bounty's anchorage, Bligh summarized the stay at Matavai Bay:

"Since I have

been here Matavai has shown itself to be a very dangerous place, a high

breaking sea

almost constantly

running over the Dolphin Bank unto the Shore, and likewise over the Bank

near to

one Tree Hill

where the sea breaks with great violence." (53)

3.7

Surfriding Conditions at Matavai Bay, 1788.

The seven major

swell events recorded in Bligh's journal in Tahiti, given his previous

nautical experience and the danger to the Bounty, certainly indicate

waves of considerable, if not extreme, size.

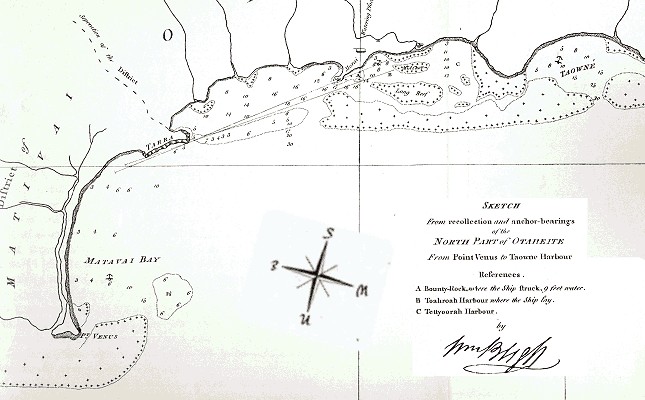

Bligh's charts record

the minimum depth of the Dolphin Bank at 2.25 fathoms, approximately 13

feet, allowing for a tidal variation of less than 12 inches. (54)

Basic calculations;

assuming ocean waves initially break at a depth of 1.3 times the wave height

(55);

give a minimum wave height of approximately 10 feet to break on the Dolphin

Bank.

To break on the

outer limits of the reef (at six fathoms or 36 feet), the estimated wave

height is approximately 27 feet.

Bligh's and Morrison's

reports indicate some of these swells were probably to the larger end of

this range.

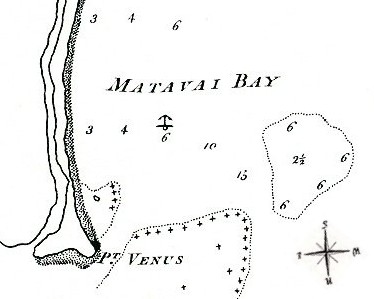

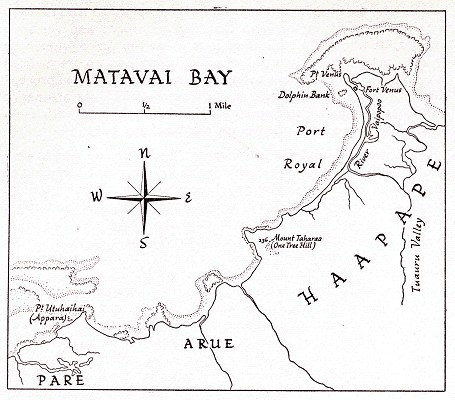

| Image right:

The "Bounty's" anchorage at Matavia Bay, Tahiti 26th October to 24th December, 1788. (56) The compass alignment

is an poor approximation.

As a result of two

extreme surf events that threatened the safety of the ship, Bligh moved

the Bounty to Toaroah Harbour for the remainer of the visit, departing

Tahiti on Sunday 5th April 1789.

|

|

The prevalent wind

direction reported during the impact of the large swell events indicate

strong on-shore winds (W and NW) at Matavai Bay, less than ideal conditions

for

surfriding.

However, these swells

ran for several days before and before and after the peak impact and alternative

wind directions were in evidence.

The log records

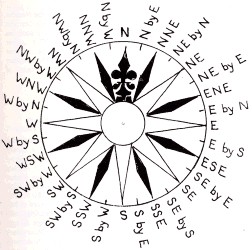

a significant number of days where the swell was fanned by offshore winds,

approximately anywhere in the quadrant from NE to SE.

On Friday 19th December,

with the onset of the fourth major swell event, the log records the wind

as ESE to ENE and Bligh writes:

"Towards Morning

a long Swell began to set into the Bay and by Noon broke

across the

Dolphin Bank altho the Wind fresh off the Shore" (57)

Sublime surfriding

conditions occur with the combination of suitable bottom contours, signficant

swell, off-shore winds, warm air and warm water temperatures.

For the duration

of the Bounty's stay in Tahiti, the temperature ranged between 76

and 85 degrees Farenheit, or 25 to 29 degress Celsius.

Without historical

documentation, it is probably safe to assume the water temperature was

similar to the present range:

"The water

temperature averages 26° C in the winter and 29° C in the summer,

with less

than one degree of variation from the surface down to 45m." (58)

While the extreme

swell conditions at Matavai Bay, vastly different to his visit with Cook

in August-September 1777, came as a suprise to Bligh, they were probably

eagerly anticipated by the Tahitian surfriders.

Joseph Banks wrote

in 1769:

"The people excell much in predicting the weather, a circumstance of great use to them in their short voyages from Island to Island.

They have many various ways of doing this (Banks notes one method); and in this as well as their other predictions we found them indeed not infallible but far more clever than Europreans." (59)

One critical observation

from a study of these accounts that must be stressed is the relative rarity

of such extreme and sublime surfriding conditions.

(60)

These conditions

are not in evidence during the winter visits of Wallace (June 1767), Cook

(May 1769, May 1774, August-September 1777) and Bligh's second voyage to

transport breadfruit to the West Indies (July 1792).

While the possibly

of such events was undoubtedly increased with Bligh's extended stay, the

critical factor was seasonal - the visit of the Bounty coincided

with Matavai Bay's direct exposure to the summer northern swells.

If the Bounty

had arrived at Tahiti four weeks later when the north swells were running,

it is likely Bligh would sought an alternate anchorage.

The reports by Cook's

crew and the subsequent post-contact accounts in Tahiti and Hawaii, where

the expedition commanders invariably sought anchorages protected from the

predominant swell direction, must be examined in this context.

3.8

James Morrison, 1788.

James Morrison was

boatswain's mate on the Bounty and was one of the mutineers.

His journal is a

highly detailed account of ancient Tahitian culture, significantly enhanced

by his extended stay in Tahiti from 1788 to1791.

(61)

Morrison's long-term

exposure, covering the full twelve month climatic cycle, to traditional

culture contrasts markedly with the relatively short-term visits to Polynesian

islands by most Europeans in the 18th century.

Furthermore, his

dramatic account of surfriding is enhanced by the extreme swell conditions

that caused Bligh and his crew considerable difficulty and threatened the

safety of the ship.

James Morrison's

account essentially replicates the earliest Hawaiian surfriding reports.

This report, although in an attached overview of Morrison's stay in Tahiti, specifically dates the surfriding activity to the fourth of the extreme swell events, with an estimated wave height between 10 and 27 feet, reported and discussed above.

"This Diversion took place during the time the Bounty lay in Maatavye (Matavai) Bay when the Surf from the Dolphin Bank ran so high as to break over her, and we were forced to secure the Hatches expecting the Ship to go on shore evry Minute." (62)

Morrison describes some of the basic elements of surfriding, as previously recorded by Banks, except that the most skilled ride in a standing position:

"they get peices

of Board of any length with which they swim out to the back of the surf,

when they Watch the rise of a surf somtimes a Mile from the shore &

laying their Breast on the board, keep themselves poised on the Surf so

as to come in on the top of it, with amazing rapidity watching the time

that it breaks, when they turn with great Activity and diving under the

surge swim out again towing their plank with them ... some are so expert

as to stand on their board till the Surf

breaks" (63)

The description of

the board "of any length" indicates a significant range of

dimensions; probably determined by skill, body size, social status and/or

the materials available for construction.

Certainly the boards

were specifically constructed for surfriding, and not an adaptation as

possibly implied by Joseph Banks and indicated by William Bligh, discussed

below.

Riding in a standing

position was not noted by members of Cook's third Pacific voyage and does

not appear to be confirmed in accounts from Hawaii until circa 1825 by

Rev. William Ellis.

(64)

The minimum surfboard

dimensions for successful riding in the standing position are open to debate.

(65)

Furthermore, Morrison

gives some some indication of the extreme surf conditions favoured by Tahitian

surfriders, indicating the rider's preference for a critical wave shape

and the potential maximum wave height and the length of the ride.

The distance from

the beach, "a mile", is consistent with the previously estimated

wave heights.

"When the Westerly Winds prevail they have a heavy surf Constantly running to a prodigious height on the Shore ... the part they Choose for their Sport is where the Surf breaks with Most Violence ... they Watch the rise of a surf somtimes a Mile from the shore" (66)

He reports that

the arrival of large surf was a significant community event and surfriding

was practised by both sexes and all ages.

The potential dangers

were substantially reduced with the selection of suitable ("smaller")

conditions and the skill of swimming taught at an early age.

"at this diversion

both Sexes are Excellent ... the Children also take their sport in the

smaller surfs and as Most learn to swim as soon as walk few or no accidents

happen from Drowning....

They resort

to this sport in great Numbers and keep at it for several Hours." (67)

The number of riders is considerable, enough to require those paddling out to avoid those riding in:

"as they often

encounter each other in their passage out and in they require the

greatest Skill

in swimming to keep from running foul of each other " (68)

This was not always successful, but such collisions were apparently considered an integral part of surfriding and the occassional "very Coarse landing" suffered without rancour or dispute:

"which they somtimes cannot avoid in which case both are Violently dashd on shore where they are thrown neck & heels and often find very Coarse landing, which however they take little Notice of and recovering themselves regain their boards & return to their sport." (69)

Morrison briefly records Tahitian canoe surfriding, confirming the earlier report of William Anderson and the contemporary account by Bligh, below.

"They have also a diversion in Canoes, which they steer on the top of the Surf with Great dexterity, and can either turn them out before it breakes or land safe tho it Break ever so high." (70)

3.9

Royal Tahitian Surfriding, 1788.

Significantly James

Morrison's account notes the expert surfriding skills of the Tahitian ruling

class, consistent with Polynesian legends but not recorded in the earliest

accounts from Hawaii by Europeans. (71)

"The Chiefs

are in general best at this as well as all other Diversions, nor are their

Weomen behind hand at it.

Eddea is one

of the Best among the Society Islands & able to hold it with the Best

of the Men Swimmers." (72)

Note that the assessment

of Iddeah's (Morrison's

Eddea) surfriding skill may not be Morrisson's

independent view, but was probably based on the communal consent of Tahitian

surfriders.

It is unlikely to

be the result of some organised competitive event.

See Chapter 1 (in

preparation).

Iddeah and her husband

Tu (also known as Otoo, named as Tinah by Bligh) formed a

personal and commercial relationship with Bligh. (73)

Upon first meeting

her on board the Bounty at Matavai Bay in October 1788, Bligh wrote:

"His wife (Iddeah) I judged to be about twenty-four years of age: she is likewise much above the common size of the women at Otaheite, and has a very animated and intelligent countenance." (74)

Three months later, while preparing to depart Tahiti, Bligh affirmed his initial assessment:

"she is one of the most intelligent persons I met with at Otaheite." (75)

Besides her surfriding

skills, Iddeah's social, physical and mental prowess was considerable.

Invited to witness

a wrestling competition, Bligh reported:

"Iddeah was

the general umpire, and she managed with so much address

as to prevent

any quarrelling, and there was no murmuring at her decisions." (76)

A mother of several children; with (a somewhat surprised) Bligh she discussed and demonstrated native childbirth, and was highly amused by his account of English methods. (77)

Some of Iddeah's other talents were less maternal:

"Iddeah has

learnt to load and fire a musquet with great dexterity, ...

It is not

common for women in this country to go to war, but lddeah is a very resolute

woman, of a large make, and has great bodily strength." (78)

On a day recorded

as one of the most extreme surf condtions (5th-6th December), her canoe

paddling skill was outstanding.

Bligh's journal

notes:

"The sea broke

very high on the beach; nevertheless, a canoe put off, and, to my surprise,

Tinah, his wife (Iddeah), and Moannah, made their way good

through the surf, and came on board to see me.

There was

no other person in the canoe, for the weather did not admit of useless

passengers: each of them had a paddle, which they managed with great activity

and skill." (79)

Ten years later,

Iddeah's son was now the local chief, Pomare.

Circa 1798, the

newly arrived English missionary, John Williams, post-dated James

Morrison's report of her surfing skills:

"The women are very dexterous at this sport; and Iddeah, the queen-mother, is considered the most expert in the whole island." (80)

3.10

William Bligh, 1788.

Following the second

major swell event at Matavai Bay, on Friday 28th November William Bligh

also briefly reported canoe surfriding; confirming the accounts of William

Anderson and James Morrison.

They also practise

with small Cannoes in these high surfs, and it is seldom that any of them

get

overturned

or filled. " (81)

He was more expansive on the subject of Tahitian surfriders, apparently using canoe paddles as surfcraft, recording some of the basic elements of surfriding (paddle-out, take-off and ride-in) and, like Banks, notes the potential danger of the activity.

"The heavy

surf which has run on the shore for a few days past has given great amusement

to many

of the Natives,

but is such as one would suppose would drown any European.

The general

plan of this diversion is for a number of them to advance with their paddles

to where the

Sea begins

to break and placing the broad part under the Belly holding the other end

with their Arms

extended at

full length, they turn themselves to the surge and balancing themselves

on the Paddles

are carried

to the shore with the greatest rapidity." (82)

Given this report

parrallels James Morrison's, there is a remote possibility Bligh's description

of the surfcraft as "paddles" is misleading, although Bligh's reputation

for exactitude makes this highly unlikely.

Joseph Banks, assisted

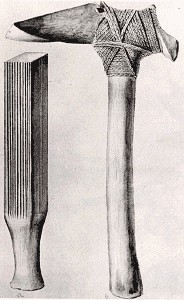

by J. C. Beaglehole's Footnote, describes Tahitian paddles as:

" a long handle

and a flat blade resembling more than any thing I recollect a Bakers peel

Footnote:

The shovel used to place bread in the oven and withdraw it. "

(83)

The use of inverted

canoe paddles is confirmed by the method of "placing the broad part

under the Belly holding the other end with their Arms".

Such a technique

was unlikely to be suitable in deep water and the paddles were probably

used close to the beach.

One, highly spectulative,

senario is that the extreme and sublime conditions placed such high demand

on the available surfboards that canoe paddles were used by some surfriders

as substitute craft.

The use of canoe

paddles as surfcraft by ancient surfriders invites further speculation.

(84)

Laurie McGinness (1997) partially quotes Bligh's report (85) and comments:

"The sport

was very crude in those early years.

They did not

have specially constructed boards, but simply used paddles, presumably

from their canoes.

Nor, apparently,

did they attempt to trim across the wave, but rode straight in to the shore.

Surfing of

this type was widespread throughout Polynesia.

It had no

cultural importance and took no great skill to perform.

Only in Hawaii

did surfing develop significantly." (86)

To some extent this is an understandable analysis based on Bligh's edited report, however James Morrison's account obviously contradicts several of McGinness' conclusions.

Like Morrison, Bligh also notes the potential for riders colliding and notes such encounters are successfully avoided by "duck-diving":

"As several

seas follow each other they have those to encounter on their return, which

they do by

diving under

them with great ease and cleverness." (87)

Bligh confirms previous assessments of the rider's pleasure and notes the practical advantages of swimming and surfriding skills.

"The delight

they take in this amusement is beyond anything, and is of the most essential

good for

them, for

even in their largest and best Cannoes they are so subject to accidents

of being overturned

that their

lives depend on their swimming, and habituing themselves to remain long

in the Water. " (88)

The question of why Bligh did not make the connection between Tahitian and Hawaiian surfriding, given that he probably saw or, at the least, heard reports of Hawaiian surfriding ten years earlier with Cook in 1778-1779, remains unanswered.

3.11

George Tobin, 1792.

Bligh was again

dispatched to Tahiti in 1791 in the Providence, accompanied by Lt.

Nathaniel Portlock in the Assistant, successfully completing the

transportation of breadfruit plants to the West Indies in 1793.

In July 1792, George

Tobin, an amateur artist and journal-keeper for the voyage, recorded juvenile

surfriding in Tahiti.

"It is common to see the children at five or six years of age amusing themselves in the heaviest surf with a small board on which they place themselves outside the breaking, whence they are driven with great velocity to the shore, fearless themselves, nor are the least apprehensions of accidents entertained by their parents." (89)

Any concerns of the

parents were, no doubt, allayed by their own familiarity with the dangers

of surfriding.

Clearly, the surf

conditions did not compare with those peviously experienced by the Bounty

in

1788-1789 and Tobin appears not to have conversed with Bligh or others

on the subject.

3.12

James Wilson, 1798.

European contact

with the already waring Polynesian chiefdoms would dramatically realign

political power, with a near terminal impact on the traditional culture.

Military power was

dependent on acquiring western firearms, munitions and sail power and the

alignment of the Bounty mutinners with the house of Tu significanly

altered Tahitian politics.

In 1797, the traditional

culture was confronted with an alternate spirituality by the arrival of

Christian missionaries from the Missionary Society (later the London Missionary

Society) on the Duff.

One of the missionaries,

James Wilson wrote of the exceptional swimming skills of the Tahitians:

"They are uniformly excellent swimmers and divers; it was affirmed that one of the natives swam from Otaheite to Eimeoi (15 miles;) he was in consequence esteemed and worshipped as a god; for they declared that as the channel was infested with numerous sharks, and the distance so great, none but a god could pass safely." (90)

His account of surfriding, highly reminiscent of Morrison, recognises the challenge of extreme conditions:

"They have

various sports and amusements; swimming in the surf appears to afford them

singular

delight.

At this sport

they are very dexterous; and the diversion is reckoned great in proportion

as the surf runs highest and breaks with the most violence: they

will continue it for hours together, till they are tired." (91)

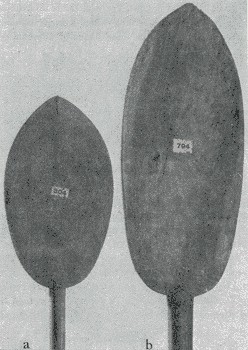

Wilson provides the earliest dimensions for Tahitian surfboards, in this case certainly ridden prone, and notes that some riders were bodysurfers.

"Some use a

small board, about two feet and a half long, formed with a sharp point,

like the fore part

of a canoe;

but others depend wholly on their own dexterity." (92)

While the basic mechanics of surfriding are effectively described, Wilson notes the stylish raising of the outside or non-steering leg, apparently indicating the riders transversed the wave face:

"They swim out beyond the swell of the surf, which they follow as it rises, throwing themselves on the top of the wave, and steering with one leg, whilst the other is raised out of the water, their breast reposing on the plank, and moving themselves forward with one hand, they are carried with amazing velocity, till the surf is ready to break on the shore, when, in a moment, they steer themselves with so quick a motion as to dart head foremost through the wave, and, rising on the outside, swim back again to the place where the surf begins to swell, diving all the way through the waves, which are running furiously on the shore." (93)

Wilson also reports surfriding is practised in smaller conditions by children and the activity, despite the inherent danger to European eyes, is essentially injury free:

"The children take the same diversion in a weaker surf, learning to swim as soon as tbey can walk, and seldom meet with any accident except being dashed on the beach; but hardly is ever is a person drowned." (94)

Whereas some writers (such as Ellis, below) make much of the potential danger of shark attack, Wilson records a remarkable response by these Tahitian surfriders:

"If a shark comes in amoung them, they surround him, and force him on shore, if they get him into the surf, though they use no instrument for the purpose: and should he escape, they continue their sport without fear." (95)

Such acts of bravado were likely directed at smaller specimens of the species.

3.13

Rev William Ellis, 1822.

The religious conversions

and the rejection of "pagan" values (96)

so eagerly sought by the missionaries failed to materialize.

Facing irrelevance

and challenged by the increasing influence of European commerical interests,

under intense local pressure the missionaries eventually provided access

to armaments, imported from the new British colony in Australia.

Again, most benefit

went to the house of Tu, now lead by his son, Pomare II. (97)

Victory by Pomare

II at the battle of Feipi in 1815 firmly entrenched the Christian church

in Tahitian politics and commerce and effectively established an alternate

state religion, directly in conflict with the traditional beliefs. (98)

In this period of

political and cultural upheaval, William Ellis arrived on island of Huahine,

north-west of Tahiti, in June 1818 with other Missionary Society members

to further advance Christianity in the Pacific islands.

Ellis moved on to

Hawaii in 1822, but after completing a tour of the major islands his wife's

illness forced a return, via America, to England. (99)

On his return he

published A Journal of a Tour Around Hawaii in 1825

(100)

and quickly followed with an expanded work, Narrative of a Tour of Hawaii

in

1826 that included a report of surfriding. (101)

In 1829 he produced

a three volume work, Polynesian Researches, detailing his

missionary experience and cultural observations in the Society Islands,

Tubuai Islands and New Zealand. (102)

Volume I included

a report of surfriding at Fare harbour on Huhaine. (103)

Polynesian Researches

was

reprinted in 1831 with the addition of a fourth volume on Hawaii including

the earlier surfriding account from the Narrative (1826) and the

earliest printed surfriding illustration. (104)

While Ellis's report

of surfriding at Huhaine certainly preceeds the Hawaiian account, the publication

dates appear to imply the reverse.

Interpretation is

further complicated by Ellis' comments that compare and contrast elements

of the two Polynesian cultures, no doubt written later in preparing his

notes for publication.

(105)

Ellis writes:

"One of their

favourite sports is the 'horue' or 'faahee', swimming in the surf, when

the waves are high, and the billows break in foam and spray among the reefs.

Individuals

of all ranks and ages and both sexes follow this sport with great avidity.

<...>

I have often

seen along the border of the reef forming the boundary line to the harbour

of Fare in

Huahine, from

fifty to a hundred persons of all ages, sporting like so many porpoises

in the surf that

has been rolling

with foam and violence towards the land; sometimes mounted on the top of

the

wave, and

almost enveloped in spray, at other times plunging beneath the mass of

water that has

swept like

mountains over them, cheering and animating each other; and by the noise

and shouting

they made

rendering the roar of the sea and the dashing of the surf comparatively

imperceptible." (106)

The surfriding breaks are located at the channels through the surrounding coral reefs:

"They usually

selected the openings in the reefs or entrances of some of the bays, where

the long

heavy billows

rolled in unbroken majesty upon the reef or the shore." (107)

Ellis's account, apart from the naming of the board, closely corresponds with the previous report by James Morrison at Matavai Bay:

"They used

a small board, which they called papa faahee- swam from the beach to a

considerable

distance,

sometimes nearly a mile- watched the swell of the wave, and when it reached

them, resting

their bosoms

on the short, flat-pointed board, they mounted on its summit, and amid

the foam and

spray rode

on the crest of the wave to the shore; sometimes they halted among the

coral rocks, over

which the

waves broke in splendid confusion." (108)

The Tahitian name

for the surfboard, "papa faahee", is similar to the Hawaiian "papa

he'e nalu", transcibed by Rev. Ellis circa 1824 as "papa hi naru".

(109)

He records variatrions

of the island pull-out, originally noted by Banks and also reported by

Morrision, and notes the relative lack of danger for skilled riders:

"When they

approached the shore, they slid off the board, which they grasped with

the hand, and either fell behind the wave or plunged towards the deep and

allowed it to pass over their heads.

Sometimes

they were thrown with violence upon the beach, or among the rocks on the

edges of the

reef.

So much at

home, however, do they feel in the water, that it is seldom any accident

occurs." (110)

As previously noted, Ellis compares Tahitian and Hawaiian surfboards and the respective surfriding populations:

"Their surf-boards are inferior to those of the Sandwich islanders, and I do not think swlmming in the sea as an amusement, whatever it might have been formerly; is is now practiced so much by the natives of the South, as by the North." (111)

The inferiority of

the boards perceived by Ellis probably refers to the larger dimensions

and/or the fine polished and stained finish that he noted of the the Hawaiian

boards. (112)

The comparison of

the popularity of surfriding between the two island groups, "not ...

now practiced so much by ... the South (Tahiti), as by the North

(Hawaii)",

may

reflect a recent rapid deterioration in the traditional culture under the

impact of divergent European influences, but this discrepancy in numbers

was probably always the case given the Hawaiian islands larger population,

larger landmass with greater natural resources and the superior quality

and quantity of the Hawaiian surf.

Ellis relates the danger of shark attack to surfriders from both locations:

"Both were

exposed in this sport to one common cause of interruption; and this was,

the intrusion of

the shark.

The cry of

a 'mao' among the former (Tahiti), and a 'mano' among the

latter

(Hawaii), is one of the most terrific they ever hear;

and I am not surprised that such should be the effect of the approach of

one of

these voracious

monsters.

The great

shouting and clamour which they make, is principally designed to frighten

away such as

may approach.

Notwithstanding

this, they are often disturbed, and sometimes meet their death from these

formidable

enemies. (113)

The danger of shark

attack is reported by other 18th century commentators, however in most

cases they detail attacks as the result of vessels breaking up at sea,

the sharks progressively consuming the survivors.

Such an account

is provided by Ellis himself. (114)

Statisically, in

modern times the number of fatal sharks attacks on surfriders in the surf

zone is small compared to the danger in the open ocean or enclosed bays

and rivers.

Athough shark numbers

were significantly reduced during the twentith century by fishing and,

in some places, by a policy of extermination (115),

Ellis possibly exaggerates the danger to surfriders for dramatic effect.

3.14

J. A. Moerenhout, circa 1834.

J. A. Moerenhout was a merchant and diplomat

who travelled from Valparaiso, Chile, at the end of 1828 to the Pacific

islands, spending most of his onshore residence in Tahiti.

His book (116)

is a thee part treatise on Polynesia. composed following a return to France

in 1834 and only occassionally quotes directly from his journal entries.

The formating of the work, with a myriad

of sections and sub-sections, is sometimes confusing.

The text makes it clear that Moerenhout

is familiar with the works of the early European explorers and the author's

preface notes that he had read "the works of the missionaries",

including the Rev. William Ellis (who reported surfriding at Fare, Huahine

circa 1820).

"I had at my

disposal scarcely anything more than the works of the missionaries, some

of which, it is true, offer interesting facts.

Mr. Ellis's,

among others, has often indicated to me most significant points of my research."

(117)

The First Part details the geography of

a large number of Polynesian islands, with the noteable exception of the

Sandwich (Hawaiian) Islands.

These reports include some accounts of

Polynesian surf skills and some descriptions of Polynesian canoes.

While the book makes several comparative

references to the Sandwhich Islands, Moerenhout does not specifically record

his landing there. (118)

The Hawaiian references may be derived

from Moerenhout's written sources, especially Ellis.

Moerenhout first encounters the power of the Pacific swells at Pitcairn Island, the current residence of some of the Bounty mutineers and their Tahitian companions, in 1829:

" 'On that

day there was a strong gust from the north, which could be felt even in

our water; the sea, rolling in long waves, also broke with such a din on

the rocks with which the island is surrounded on all sides that it seemed

unapproachable to us, even for the smallest boats.

We finally

arrived at the watering place, but without being able to make out the little

bay on account of the violence of the waves.' " (119)

Polynesian aquatic skills in these conditions

were demonstrated by one of the Tahitians successfully steering the longboat

to a landing (see a later account, below) and their calm conrol in extreme

conditions, although the estimated wave height, "more than twenty feet",

may be an exaggeration..

After landing the longboat on the shore,

Moerenhout (quoting from his journal) writes:

" 'I had left

the boat, seeing around me only rocks almost like peaks, looking for some

indication of a route or some kind of path and not being able to find one,

when I heard the two islanders who accompanied us cry to the sailors: Save

yourselves, Save yourselves!, and, turning around, I saw a horrible wave

of more than twenty feet in height rollover them.

The natives

held the boat with a long rope.

Our sailors

were saved, but not without taking on part of the wave, which broke on

the rock with the noise of thunder, hit, them, and caused them to be swept

away.

I was a witness

then of one of the most singular sights that I have seen in my life.

These two

islanders, fixing themselves on the rock with their sinewy arms, held the

boat's rope, looked calmly at the coming sea, and at a signal which they

gave to each other crouched down simultaneously to let the mass of water

rollover them.

I believed

them to be lost when, a moment later, to my great astonishment, I saw them

get up as if nothing had happened, a maneuver which they repeated up to

three times; but then the sea, a little more calm, let them recall the

sailors and let them leave with the boat from that little bay, which they

then said was not safe on that day.' " (120)

The swimming skill of the Tahitians at Pitcairn in the surf zone is beyond Moerenhout's powers of description:

" 'One of the

natives again seized the helm to allow the boat to clear the pass, and

as soon as we were led out he wished us good day and jumped into the sea.

He swam in

the midst of waves and breakers with a skill which you would have to see

to get a true idea of, and in a few minutes we saw him safe and sound on

land.' " (121)

On the 29th February 1829, the skill of shooting a wave in a longboat is demonstrated in the vincinity of Lord Hood Island by one of the "Pitcairn people":

" 'In approaching

the land our pilot had the boat stop for more than a quarter of an hour,

not far from the reef, beaten by the sea with a rage which seemed not to

be going to let us land, while a number of enormous sharks surrounded our

boat, appearing to look at us as assured prey if the waves capsized us

or broke us on the rock.

The men in

the little dugouts had, however, already reached land and stayed on the

reef, ready to receive us.

Seizing a

favorable moment our pilot cried to the sailors to row, and finally carried

by the crest of a wave which took us at a frightful speed, we landed in

a few seconds on the reef, amid floods of foam.' " (122)

Later, writing about Tiooka and Oura (Taaroa and Taapouta of the Indians) and the neighbouring islands, Moerenhout's account shows advanced surf-swimming skills are also practised in the Marquesas Islands:

"Since the

sea was too high to be able to land on the reef and the noise of the waves

did not allow us to be heard from that distance, I gave them a signal to

come, but they refused.

Then my servant,

born on the Marquesas, threw himself into the sea and, crossing the surf

by swimming, arrived on the reef in a few minutes, where he was covered

with caresses by the Indians, so gentle and simple when circumstances do

not make them depart from their true character." (123)

On Moerenhout's second voyage in 1832 he

visited Matavai Bay, the anchorage of Wallis, Cook and Bligh (see above),

that had been superceded as a port by Papatee by this time.

While not recorded as a location for surfriding,

Dolphin Reef and its exposure to summer swells is noted.

"Before arriving

at Point Venus we drew back a distance from the coast because of a reef

which extends to the east of this point nearly two miles from land, being

the more dangerous in that it is still hidden under the water.

A whaling

ship had almost been lost there about two years before.

After having

doubled this point we again hugged the land, skirted the reef indicated

in all its north-west part by the waves which break over it continually.

We were close

enough to see Matavia distinctly and the bay where in 1766 Wallis came

to anchor, to the great astonishment of the islanders.

It was also

in this bay, or rather in this roadstead, that Cook cast anchor each time

he visited Tahiti.

On entering

the pass Wallis touched on a rock or part of the reef which he called Bolphin's

(sic,

Dolphin) rock.

The reef exists

today and has scarcely increased since, which can be explained, in my opinion,

by its position in the center of the pass.

There is in

fact a continual current there occasioned by the river, quite large at

this spot, and by the sea water, which, dashed over the reef in all the

eastern part, returns to the sea following the pass of Matavai.

This unsafe

bay is used only by warships, which are in danger there from November to

May.

I spoke in

the tale of my first voyage to Tahiti of the serious damage which the Russian

warship the Croky experienced there in 1830."

(124)

This First Part records further examples of the skill of Polynesian canoe paddlers (125), the effectiveness of their observations at sea (126) and several descriptions of Polynesian canoes (127).

The Second Part, Ethnography (which contains the surfriding report), is based on the totallity of Moerenhout's readings and observations across Polynesia.

"The second will present, under the title of Ethnography, all the remarks which my long stay in these countries and my relations with the inhabitants have allowed me to gather relative to their language, their religion, and their customs." (128)

In this part, the various Polynesian settlements are treated as one culture, therefore determining the chronolgy or location of the reports is usually impossible, except where some special variations are reported as in the discussion of canoe racing noted below.

In the Second Part: Ethnography, Chapter Three: Customs, II: Private Customs, A. Education, Moerenhout writes:

"... what pleased

them the most was to play in the water.

In that fiery

climate water was for them a second element, in which they spent at least

a quarter of their lives.

Scarcely had

it been born when the mother carried her child to the river, and from that

moment on until he could take care of himself she washed him several times

a day; as a result children in general knew how to swim almost as soon

as they knew how to walk." (129)

In the Second Part: Ethnography, Chapter Three: Customs, II: Private Customs, C. Domestic Life, Section Thee: Pleasures, 3. General Festivities (Taupitim or Oron), Moerenhout writes of the popularity of canoe racing and notes some of the inter-island variations.:

"It was the

areois and the fatou note paupa which were most in favor and attracted

the greatest crowd, although in several places there were a great number

of other diversions, the principal ones of which were:

...

4. The fatiti

achemo vaa, a dugout race."

This was the

favorite amusement of the inhabitants of Tongatabou and other Friendly

Islands, and the superior performance of their dugouts made them just as

formidable in sea fights as their swiftness in running in land battles.

Dugout races

were not the custom at all in the Society Islands, and they were not held

except in the great festivals and in the public merry-making.

For a purpose,

as in the foot races, they had some flag, which the victor took away.

All the dugouts,

whatever their size, could enter the contest, but never more than two at

a time, from the smallest paddled by only two persons, to the double dugouts,

which often had twelve to twenty.

Once the signal

for departure was given the rivals' craft were followed by a great number

of others, which had to keep behind them all the time; the people who were

in them uttered cries and tried to encourage them, each one the backer

of his side, along with the crowd, which kept on the shore or endeavored

to follow the direction of the dugouts in their course.

The tumult

continued to increase from the moment of their arrival, the moment in which

a piercing cry from the conquerors was heard and from all those on their

side, which they repeated up to three times, raising their arms and waving

their flags and other objects in the air.

These demonstrations

were repeated for each of the couples engaged in the contest; and from

the pleasure which they seemed to take in this amusement, it was astonishing

that it was not more generally extended.

In the Friendly

Islands the dugouts also met with sails.

These games

were so much the more brilliant in that they took place in a calm and serene

time and in that the spacious bays formed by the coral reefs which surrounded

all the islands were moreover natural bays, the most suitable in the world

for that type of exercise. (18, Footnote)

(Footnote) 18. The inhabitants of the Friendly Islands attached such an importance to the construction of the dugouts intended to meet in these public contests that, after they had been launched and tried out, those which did not respond to their expectations and the speed of travel were immediately condemned and destroyed." (130)

In the same section, General Festivities, other activities are noted:

"There were still a number of other common amusements, some of them daily, which didn't stop them from devoting themselves to them during solemn festivities." (131)

Included in these "other common amusements" is surfriding:

"3. The horoue

or goroue, which consisted in letting themselves be carried by the

ocean waves, keeping on the top.

The most agreeable

amusement for them of all those which had been created for the water.

For its theater

this exercise had openings in the reefs, places where the sea broke with

the greatest furor.

Among all

the feats or skills which men in different countries have succeeded in

doing I know of none which surpasses this one or which causes more astonishment

at first sight.

Generally

they have a plank three to four feet long with which they take to the sea

at a certain distance, waiting for the waves, diving under those which

are not strong enough, and letting several of them roll over their heads

until a very high one comes along, which cries from the spectators on the

shore announce to them, always gathered in great numbers along the shore.

Lying on their

plank they wait for their wave, and at the instant when it approached them

they give themselves a movement which lets them reach the crest, from which

they are seen immediately carried with the rapidity of an arrow towards

the shore, which you would think they would be thrown upon in tatters,

but when they are very close, a little movement returns them and gets them

to leave the wave, which at the same instant breaks with a crash on the

sand or on the rocks, while the Indian afloat, and without ever leaving

his plank, leaves while laughing to start his terrible play over again.

Men and women love this diversion with a furor and practice it from their

youngest years; some of them gain a skill which goes beyond all belief.

I have seen

some of them in very bad weather jump to their knees on their plank and

hold themselves so in equilibrium while the flood carries them with a terrifying

speed." (132)

The text certainly indicates the Moerenhout

saw surfriding, however it is unclear if his observations were confined

to Tahiti (the island of longest residence) or if surfriding was also noted

on other islands.

The inclusive format adopted in Part II

would tend to imply the activity was widespread.

Moerenhout gives a description of basic

surfriding activity (the paddle-out, wave selection, the take-off, the

ride and the dismount) and, echoing Banks and Ellis, locates the activity

at "openings in the reefs, places where

the sea broke with the greatest furor".

He also reports

that surfriding was practised by both sexes of all ages and was a community

event with "spectators ... always gathered in great numbers along the

shore."

Importantly, Mereonhout

records some advanced surfriding skills, the riders "jump to their knees

on their plank" on, apparently, large swells ("in very bad

weather").

He estimates the

length of the Tahitian boards as "three to four feet long", substantially

longer than the only other specific account ("about two feet and a half

long") by James Wilson in 1789.

As previously noted, Moerenhout credits the journals of the early missionaries in the Preface and there are some similarities, noteably the use of the indigenous name, with the surfriding account at Fare on Huahine by Rev. William Ellis, above.

3.15

C. F. Gordon-Cummings, c 1883.

Continuous outbreaks

of internal conflict, Chrisian evangelism, commerical exploitation and

the ravages of introduced diseases on the native population preciptated

a rapid decline in traditional culture and the old religion.

(133)

At the time of Cook's

first visit in 1769 the population of Tahiti was probably about 40,000.

By 1800 it plummeted

to less than half that; by 1840 the native popuation was 9,000 and continued

to decline even further. (134)

With the increasing

challenge to Brtish power by France and the Roman Catholic church in the

late 1830s, the situation deteriorated into another war, culminating in

the surrender of Tahitian political power to France in 1847. (135)

Towards the end of

the 19th century many traditional activities had virtually disappeared.

Several visitors

to the Society Islands who had some knowledge of surfriding, probably from

Hawaii, and were aware of the earlier surfriding accounts there, failed

to observe the activity.

In the early 1880s, C. F. Gordon-Cumming, no doubt reflecting on Rev. Ellis' account of the numerous riders at Fare, commented:

"Surf-riding

was formerly a characteristic sport in most of these groups, and especially

at Tahiti, where fifty years ago it was the favorite pastime of men, women

and children.

There, however,

it has fallen so entirely into disuse, that during the six months I remained

in the Society Isles I never once saw it." (136)

Her "negative report" is similar to the account of Henry Adams, below.

3.16

Henry Adams, 1891.

Henry Adams, indicating

the domination of Christian worship over the traditional culture, reported

from Tahiti circa 1891:

"If they have

amusements or pleasures, they conceal them.

Neither dance

nor game have I seen or heard of; nor surfing, swimming, nor ball-playing

nor anything but the stupid, mechanical himene (hymn-singing)."

(137)

3.17

Tueria Henry, 1928.

The only indigenous

writing on Tahitian surfriding is by Tueria Henry, published by the

Bishop Museum Press in 1928.

The work was based

on material collected by John M. Orsmond, a contemporary of fellow missionaries

John Williams and William Ellis.

Unfortunately, her

entry for surfriding in a retrospective of Tahitian sports essentially

replicates Rev. Ellis' report circa 1820 and offers no substantial insights,

apart from contradicting Gordon-Cumming and Adams in noting that it is

still practised:

" 'Fa'ahe'e",

surf-riding, was much indulged in, mostly by young men and women in favorable

places where the sea rolled in breakers over sunken rocks.

The board

used was called 'papa-fa'ahe'e' (board-for-surfriding).

The pleasure

in this sport would have been unalloyed but for sharks that sometimes came

and wounded or carried away someone out of reach of timely help.

Surf-riding

is still practised to a small extent." (138)

More interesting is the, previously unrecorded, entry for high-diving:

" 'Neue or

naue'.. plunging into water, has always been a favorite pastime of children

and grown people.

They plunge

off high cliffs into the deep sea or off rocks and trees into deep fresh-water

pools, and they swim and dive like fishes.

Diving is

called 'titi-aho-roa' (holding-long-breath), and swimming is called 'au'."

(139)

While underwater

diving and swimming are obviously part of surfriding activity, high diving

parallels surfriding in the elements of "thrill' and "style".

Some commentators

on Hawaiian culture, noteably John 'Ii, also detail high diving activities.

(140)

3.18

Ben Finney, 1956.

In preparing material

for his master’s thesis in anthropology at the University of Hawai’i, Ben

Finney travelled throughout the Pacific.

In a paper on Tahitian

surfriding (141), one of several

deriving from the thesis (142), he