|

surfresearch.com.au

thrum's almanac : surf-riding, 1896 |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

Tim DeLaVega notes

that this article was preceeded by a shorter entry:

"A89 Thrum,

Thomas G (editor) :

Thrum's Hawaiian Almanac and Annual for 1892. Honolulu,

1892. page 52."

This copy of this

article is yet to be located.

He also notes that

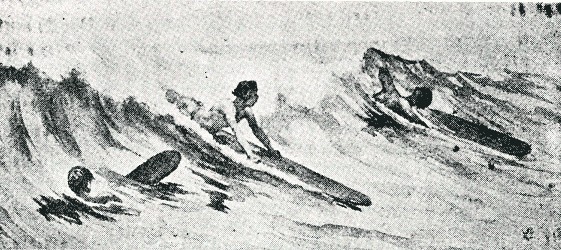

the 1896 edition features " 1 Illust., 2 Photos, One is a photograph of

3 boys paipo surf-riding."

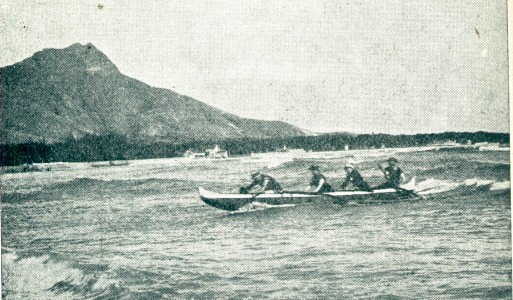

This copy of the

1896 edition has rather two illustrations and one photograph of canoe surf

riding, all reproduced below.

- DeLaVega: 200 Years (2004) page 28.

Since its publication, the article has imbedded itself in surfing literature, extensively quoted in a wide range of publications and highly praised by commentators.

Several sections

of Thrum's article were quoted in Riding the Surfboard, attributed

to Duke Kahanamoku and published in the first edition of the Mid-Pacific

Magazine in1911.

The author, actually

Alexander Hume Ford, declared it ""the best article ever prepared on ancient

surfing."

- Kahanamoku (Ford): Riding the Surfboard, The Mid-Pacific Magazine,(1911) page 4.

In his seminal book on surfriding, Hawaiian Surfriders, self-published in 1935, Tom Blake quoted extensively from Thrum's article and cited it as a highlt valuable source:

"I feel this to be the finest contribution on old surfriding in existence and am sure the 'native from Kona' knew the art of surfriding well." - page 72

He concluded :"I

can detect only one error in the work ... (the) writer says the Olo board

of wili wili was two or three feet wide." - pages 76-77.

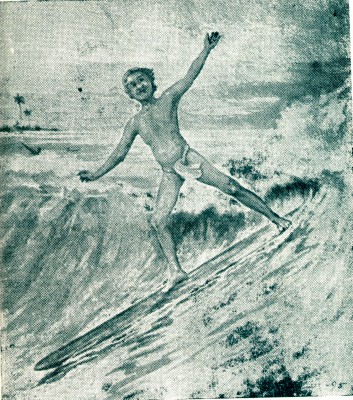

While the title illustration

has been reprinted in several books, one of the earliest being H. Arthur

Klein's Surfing

in 1965, reproduction of the second illustration is rare.

The canoe surfing

photograph was previously printed in ??

- Klein: Surfing (1965), Hawaiian Surf-riding, circa 1896 (accredited to the Public Archives), page 28.

An edited version of the article was reproduced as an appendix in Finney and Houston's 1996 reprint of their seminal work of thirty years earlier, Surfing – The Sport of Hawaiian Kings.

- Finney and Houston: Surfing – A History of the Ancient Hawaiian Sport (1996), Appendix E, pages 102 to105.

Tthe article appeared

in an anthology by Patrick Moser in 2008, without Thrum's footnotes on

page 107 and, consistent with the book's format, without the images.

In the introduction

he decribed it as an "invaluable text" in describing "the particular practices,

rituals, and tools of craftsmen who shaped the boards "

- Moser: Pacific

Pasages (2008), pages 125-131.

HAWAIIAN SURF RIDING.

AMONG the favorite

pastimes of ancient Hawaiians that of surf riding was a most prominent

and popular one with all classes.

In favored localities

throughout the group for the practice and exhibition of the sport, "high

carnival" was frequently held at the spirited contests between rivals in

this aquatic sport, to witness which the people would gather from near

and far; especially if a famous surf-rider from another district, or island,

was seeking to wrest honors from their own champion.

Native legends abound with the exploits of those who attained distinction among their fellows by their skill and daring in this sport; indulged in alike by both sexes, and frequently too- as

Page 107

(i)n these

days of intellectual development- the gentler sex carried off the highest

honors.

These legendary

accounts are usually interwoven with romantic incident, as in the abduction

of Kalea, (a) sister of Kawaokaohele, Moi of Maui,

by emissaries of Lo-Lale chief of Lihue, in the Ewa district of Oahu; the

exploit of Laieikawa, (b)

and Halaaniani at Keaau,

Puna, Hawaii; or for chieftain supremacy, as instanced in the contest between

Umi and Paiea (c) in a surf swimming match at Laupahoehoe,

which the former was challenged to, and won, upon a wager of four double

canoes; also of Lonoikamakahiki at Hana, Maui, and others.

How early in the

history of the race surf riding became the science with them that it did

is not known, though it is a well-acknowledged fact, that while other islanders

may divide honors with Hawaiians for aquatic powers in other respects,

none have attained the expertness of surf sport, which early visitors recognized

as a national characteristic of the natives of this group. It would be

interesting to know how the Hawiians, over all others in the Pacific, developed

this into the skillful or scientific sport which it became, to give them

such eminence over their fellows, for we find similar traits of character,

mode of life, mild temperature and like coast lines in many another "island

world of the Pacific."

That it became

national in character can be understood when we learn that it was identified,

to some extent at least, with the ceremonies and superstitions of kahunaism,

especially in preparations therefor, while the indulgence of the exciting

sport pandered to their gambling propensities.

The following

descriptive account has been prepared for THE ANNUAL by a native of the

Kona district of Hawaii, familiar with the subject.

For assistance

in its translation we are indebted to M. K. Nakuina, himself no stranger

to the sport in earlier days.

Surf riding was

one of the favorite Hawaiian sports, in which chiefs, men, women and youth,

took a lively interest.

Much valuable

time was spent by them in this practice throughout the day.

Necessary work

for the maintenance of the family, such as farming, fishing, mat and kapa

making and such other household duties required of them and needing attention,

by

Page 108

either head of

the family, was often neglected for the prosecution of the sport.

Betting was made

an accompaniment thereof, both by the chiefs and the common people, as

was done in all other games, such as wrestling, foot racing, quoits, checkers,

holua, and several other known only to the old Hawaiians.

Canoes, nets,

lines, kapas, swine, poultry and all other property were staked, and in

some instances life itself was put up as wagers, the property changing

hands, and personal liberty, or even life itself, sacrificed according

to the outcome of the match, the winners carrying off their riches and

the losers and their families passing to a life of poverty or servitude.

TREES AND MODE OF CUTTING.

There were only three kinds of trees known to be used for making boards for surf riding, viz.: the wiliwili (Erythrina monosperma), ulu or breadfruit (Artocarpus incisa), and koa (Acacia koa).

The uninitiated were naturally careless, or indifferent as to the method of cutting the chosen tree; but among those who desired success upon their labors the following rites were carefully observed.

Upon the selection

of a suitable tree, a red fish called kumu was first procured, which was

placed at its trunk.

The tree was

then cut down, after which a hole was dug at its root and the fish placed

therein, with a prayer, as an offering in payment therefor.

After this ceremony

was performed, then the tree trunk was chipped away from each side until

reduced to a board approximately of the dimensions desired, when it was

pulled down to the beach and placed in the halau (canoe house) or

other suitable place convenient for its finishing work.

FINISHING PROCESS.

Coral of the corrugated

variety termed pohaku puna, which could be gathered in abundance along

the sea beach, and a rough kind of stone called oahi were commonly used

articles for reducing and smoothing the rough surfaces of the board until

all marks of the stone adze were obliterated.

As a finishing

stain the root of the ti plant (Cordyline terminalis), called mole

ki, or the pounded bark of the kukui (Aleurites moluccana),

called hili, was the mordant used for a paint made with the soot

of burned kukui nuts.

This furnished

a durable, glossy black

Page 109

finish, far preferable to that made with the ashes of burned crane leaves, or amau fern, which had neither body nor gloss.

Before using the

board there were other rites or ceremonies to be performed, for its dedication.

As before, these

were disregarded by the common people, but among those who followed the

making of surf boards as a trade, they were religiously observed.

There are two

kinds of boards for surf riding, one called the olo and the other

the a-la-ia, known also as omo.

The olo

was made of wiliwili - a very light buoyant wood - some three fathoms long,

two to three feet wide, and from six to eight inches thick along the middle

of the board, lengthwise, but rounding toward the edges on both upper and

lower sides.

It is well known

that the olo was only for the use of the chiefs; none of the common

people: used it.

They used the

a-la-ia,

which was made of koa, or ulu. Its length and width were similar to the

olo, except in thickness, it being but of one and a half or two inches

thick along the center.

BREAKERS.

The line of breakers

is the place where the outer surf rises and breaks at deep sea.

This is called

the kulana nalu.

Any place nearer

or closer in where the surf rises and breaks again, as they sometimes do,

is called the ahua, known also as kipapa or puao.

There are only

two kinds of surf in which riding is indulged; - these are called the kakala,

known also as lauloa, or long surf, and the ohu, sometimes

called opuu.

The former is

a surf that rises, covering the whole distance from one end of the beach

to the other.

These, at times,

form in successive waves that roll in with high, threatening crest, finally

falling over bodily.

The first of

a series of surf waves usually partake of this character, and is never

taken by a rider, as will be mentioned later.

The ohu

is a very small comber that rises up without breaking, but of such strength

that sends the board on speedily.

This is considered

the best, being low and smooth, and the riding thereon easy and pleasant,

and is therefore preferred by ordinary surf riders.

The lower portion

of the breaker is called honua, or foundation, and the portion near

a cresting wave is termed the muku side, while the distant, or clear

side, as some express it, is known as the lala.

Page 110

During calm weather when there was no surf there were two ways of making or coaxing it practiced by the ancient Hawaiians, the generally adopted method being for a swimming party to take several strands of the sea convolvulus vine, and swinging it around the head lash it down unitedly upon the water until the desired result was obtained, at the same time chanting as follows:

Ho aei : ho ae

iluna i ka pohuehue,

Ka ipu nui lawe

mai.

Ka ipu iki waiho

aku.

METHODS OF SURF RIDING

The swimmer, taking

position at the line of breakers, waits for the proper surf.

As before mentioned

the first one is allowed to pass by.

It is never ridden,

because its front is rough.

If the second

comber is seen to be a good one it is sometimes taken, but usually the

third or fourth one is the best, both from the regularity of its breaking

and the foam calmed surface of the sea through the travel of its predecessors.

In riding with

the olo or thick board, on a big surf, the board is pointed landward

and the rider, mounting it, paddles with his hands and impels with

his feet to give the board a forward movement, and when it receives the

momentum of the surf and begins to rush downward, the skilled rider will

guide his course straight, or obliquely, apparently at will, according

to the spending character of the surf ridden, to land himself high and

dry on the beach, or dismount on nearing it, as he may elect.

This style was

called kipapa.

In using the

olo

great care had to be exercised in its management, lest from the height

of the wave - if coming in direct - the board would be forced into the

base of the breaker, instead of floating lightly and riding on the surface

of the water, in which case, the wave force being spent, reaction throws

both rider and board into the air.

In the use of

the olo the rider had to swim out around the line of surf to obtain

position, or be conveyed thither by canoe.

To swim out through

the surf with such a buoyant bulk was not possible, though it was sometimes

done with the thin boards, the a-la-ia.

These latter

are good for riding all kinds of surf, and are much easier to handle than

the olo.

Page 111

Various positions

used to be indulged in by old-time experts in this aquatic sport, such

as standing, kneeling and sitting.

These performances

could only be indulged in after the board had taken on the surf momentum

and in the following manner.

Placing the hands

on each side of the board, close to the edge, the weight of the body was

thrown ,on the hands, and the feet brought up quickly to the kneeling position.

The sitting position

is attained in the same way, though the hands must not be removed from

the board till the legs are thrown forward and the desired position is

secured.

From the kneeling

to the standing position was obtained by placing both hands again on the

board

Page 112

CANOE

SURF RIDING AT WAIKIKI.

and with agility leaping up to the erect attitude, balancing the body on the swift-coursing board with outstretched hands.

SURF SWIMMING WITHOUT BOARD

Kaha nalu

is the term used for surf swimming without the use of the board, and was

done with the body only.

The swimmer,

as with a board, would go out for position and, watching his opportunity,

would strike out with hands and feet to obtain headway as the approaching

comber with its breaking crest would catch him, and with his rapid swimming

powers bear him onward with swift momentum, the body being submerged in

the foam; the head and shoulders only being seen.

Kaha experts

could ride on the lala or top of the surf as if riding with a board.

CANOE RIDING - PA-KA WAA

Canoe riding in

the surf is another variety of this favorite sport, though not so general,

nor perhaps so calculated to win the plaudits of an admiring throng, yet

requiring dexterous skill and strength to avoid disastrous results. .

Usually two or

three persons would enter a canoe and paddle out to the line of breakers.

They would pass

the first, second, or third surf if they were kakalas, it being

impossible to shoot such successfully with a canoe, but if an ohu

is approaching,

Page 113

then they would

take position and paddle quickly till the swell of the cresting surf would

seize the craft and speed it onward without further aid of paddles, other

than for the steersman to guide it straight to shore, but woe be to all

if his paddle should get displaced.

Canoe riding

has been practiced of late years in mild weather by a number of the Waikiki

residents, several of whom are becoming expert in this exciting and exhilarating

sport.

NAMES OF SOME NOTED SURFS

1. Huia

and Ahua, at Hilo, Hawaii, the former right abreast of Kai- palaoa,

and the latter off Mokuola (Cocoanut Island).

Punahoa, a chiefess,

was the noted surf rider of Hilo during the time of Hiiakaikapoli.

2. Kaloakaoma,

a deep sea surf at Keaau, Puna, Hawaii; famed through the feats of Laieikawai

and Halaaiani, as also of Hiiakaikapoli and Hopoe.

3. Huiha,

at Kailua, Kona, Hawaii, was the favorite surf whereon the chiefs were

wont to disport themselves.

4. Kaulu

and Kalapu, at Heie, Keauhou, Kona, Hawaii, were surfs enjoyed by

Kauikeouli (Kamehameha III), and his sister the princess Nahienaena, whenever

they visited this, their birthplace.

5. Puhele

and

Keanini,

at Hana, and Uo at Lahaina, Maui were surfs made famous through

the exploits of chiefs of early days.

6. Kalehuawehe,

at Waikiki, Oahu, used to be the attraction for the congregating together

of Oahu chiefs in the olden time.

7. Makaiwa,

at Kapaa, Kauai, through Moikeha, a noted chief of that island is immortalized

in the old meles as follows:

"I walea no Moikeha

ia Kauai,

I ka la hiki

ae a po iho.

0 ke kee a ka

nalu 0 Makaiwa-

0 ke kahui mai

a ke Kalukalu-

E noho ia Kauai

a e make."

[Translation]

"Moikeha is contented

with Kauai

Where the sun

rises and sets.

The bend of the

Makaiwa surf-

The waving of

the Kalukalu-

Live and die

at Kauai."

|

Thrum's Hawaiian Almanac and Annual for 1896. Honolulu, 1896. |

Originally uploaded in 2006, this analysis was extensively revised in 2013 following an exchange of emails with Ben Marcus, many thanks to Ben for his advise and comments.

Disclaimer

1. I have not visited

the Bishop Museum in Honolulu and examined their collection of ancient

surfboards

2. Ben Marcus noted

that Ian Masterson completed his master’s thesis on the Hawaiian olo,

I have yet to access this work.

“The olo were a symbol

of royalty, and the penalty for a commoner caught riding or even touching

one of these boards was death by beheading. “

I assume this is

an extension from Thrum's “It is well known that the olo was only for the

use of the chiefs.”

The penalty is perhaps

an exaggeration, and thinking laterally:

Did the chiefs have

a retinue (of commoners) who prepared, serviced and stored their boards?

In the introduction,

Thomas Thrum establishes the status of surf riding in Hawai'ian culture

and details some of the ancient Hawai'ian legends that include surf riding

exploits, noting that they "are usually interwoven with romantic incident,

as in the abduction of Kalea."

The legends are

accredited to Laieikawai (?) and Abraham Fornander's Polynesian Race

(1878-1885),

the later containing the Legend of Kalea which, following publication,

appeared occassionally in an edited version in the Hawai'ian press.

- The Daily Bulletin, Honolulu, December 30, 1882, Supplement, page 3.

He failed to note

that the Hawai'ian archipelago was the largest and most productive landmass

in tropical Polynesia (excluding New Zealand) and supporting the largest

population.

Thrum's assesmment

that there were "like coast lines" was incorrect; as one of the youngest

of the volcanic island chains in the Pacific the Hawai'an islands have

early-phase coral reefs that lie offshore, but do not encircle the land,

for example, as in Tahiti.

These intermittent

reefs allow swell to reguarly reach the beach breaks and are themselves

surfing breaks, facilitating surf riding over a wide range of swell size

and direction.

Conversely, in Tahiti

surfriding was commonly practised where there was an "opening of the reef."

- Ellis: Polynesian

Researches (1829), Volume 1, pages 223-224.

- Moerenhout: Travels

(1837),

pages 359-360.

- Wheeler: Memoirs

(1842),

pages 273-274.

The Authors

The article purports to dicuss "ancient surfriding," that is, at the

least, before the ending of the kapu system in 1819.

Clearly, in 1896 none of Thrum's authors were old enough to personally

recall events before the end of kapu.

This in marked contrast

with the accounts by other native Hawai'ians, David Malo and John Papa

Ii, both who experienced the pre-kapu period.

In particular, David Malo was a court official who originally published

his book in 1838, but only in native Hawaiian, the English translation

was not published until 1903.

- Malo:

Antiquities (1838)

- I'i: Fragments

(1870)

Thomas Thrum

His Almanac was above all a promotional publication for the Hawai'ian tourist industry.

The Native of

the Kona district of Hawaii.

The failure to identify

the "author" beyond "a native of the Kona district of Hawaii, familiar

with the subject" is unfortunate.

Without further

information it is difficult to assess the extent of knowledge or experience

of the correspondent.

Itis unclear if

"the native" provided an original manuscript or whether this was material

contributed to one of the hawi'ian language newpaersof the period.

M. K. Nakuina

M. K. Nakuina is accredited as "the translator .. himself

no stranger to the sport in earlier days"

In 1901, Moses K.

Nakuina gave an insight into the preparation of the Annual , following

his dismissal as a government official by Thrum for "reading newspapers

in office hours."

Nakuina noted

that he completed the translation of the surf-riding article, amoung others,

during office hours, while he was employed by Thrum on government pay.

- Evening Bulletin,

Honolulu, August 2, 1901, page 6.

- Malo:

Antiquities (1838)

- Il: Fragments

(1870)

Presumably, the original

manuscript was written in native Hawa'ian, hence the translation, as made

by " M. K. Nakuina, himself no stranger to the sport in earlier days."

It is unclear if

Nakuina performed a faithful translation, or made some adjustments based

on his personal knowledge, and to what extent Thrum subsesquently edited

the English transcription.

There is a remote

possibility that the original article was published in an native language

paper of the preriod.

The Kona native wrtites

of surf riding as enjoyed by all classes, gender and ages, often to the

detriment of domestic needs.

Several commentators

note the abandonment of productive activity by whole villages in pursuit

of surfing, however they usually associate this with various religious

festivals.

It is more likely

that these occasions were prompted by the arrival of quality surf, if this

coincided with a festival, all the better.

He also notes that surf riding was a focus of gambling where goods and personal liberty were waged on the "outcome of the match."

Construction

"There were only

three kinds of trees known to be used for making boards for surf riding,

viz.: the wiliwili (Erythrina monosperma), ulu or breadfruit (Artocarpus

incisa), and koa (Acacia koa)."

The Latin names

were, no doubt, added by Thrum.

The earliest description

of the timber used for Hawai'ian surfboards is William Ellis' "very light

sharkboards," on Kauai in 1778.

Rev. William Ellis

reported "erythrina" (willi-willi) on Hawaii in 1825 and David Malo

recalled both willi-willi and koa in 1838.

Breadfruit was recorded

as the timber of choice for the surfboard riders at Hilo by Nordhoff and

Bird in 1873.

In 1892, William

Brigham, an early curator of the Bishop Museum, noted that surfboards were

"usually made of koa," and "sometimes ... of very light wi-Ii wi-Ii."

He inferes that

willi

willi is only used for the "narrow, o-lo."

Tom Blake (1935) quotes extenstively from the article ( pages 44 to 47) and concludes ...

I can detect

only one error in the work.

That writer

says the olo board of wili wiIi was "two or three feet wide."

This makes

the board too wide to paddle comfortably and also too wide to give a good

performance.

The width

of the olo board was from one to two feet wide, instead of from two to

three.

I also infer,

from that error, the writer to be unfamiliar with the wiIi wili, or chief's

board.

It is also

evident from his writing that the olo, or long thick board, was not made

of koa and ulu, but of only wili wili.

Therefore,

Paki's

boards of olo design and made of koa are an exception and not the rule.

They really

are too heavy to please the average surfrider.

On the other

hand, we have today an enthusiastic and skillful surfrider, Northrop Castle,

who has a board weighing more than either of Paki's.

Castle's board

weighs about two hundred pounds, and he likes it.

Rather than finding

the reported Olo width questionable, this inconsistancy may be the result

of ineffective translation and/or transcription from the original source.

Possibly, the translation

may have also required the calcuation of the dimensions into feet and fathoms

(approximately six feet) from a different method of measurement.

Two traditional Hawaiian

measurements were (note these lack full Hawaiian punctuation) ...

po'ae'ae :

1. the distance from the armpit to the finger tips of the outstretched

arm. (Kalokuokamaile)

2. Armpit

(PE). (Approximately 30 inches or 760 mm).

kiko'o : the

distance between the extended tips of the thumb and forefinger of

one hand, used to measure the depth of a canoe. (Emerson; PE) (Approximately

8 inches or 200 mm).

- Adapted from Holmes

(1993),

Glossary,

pages 172 to 179.

If these traditional

measurements are substituted, then the approximate dimensions would be

16 to 24 inches wide (two or three kiko'o) and 90 inches - 7 foot 6 inches

long (three po'ae'ae).

Existing ancient

Alaia dimensions would be close to this - but not for the Olo.

I

f Blake is correct

in his inference that the writer is "unfamiliar with the wiIi wili,

or chief's board",

then the accuracy of other aspects of the article

may be called into question.

Also note that the report indicates the for the Alaia "a-la-ia ... length and width were similar to the olo except in thickness, it being but of one and a half or two inches thick along the center."

That is the only

difference between these designs is the timber and the thickness..

The Olo is made

of "wili wili" and the Alaia "of koa, or ulu."

The Olo is "from

six to eight inches thick", the Alaia "one and a half or

two inches thick".

The reported length

of the two designs is identical, that is "three fathoms long (18

feet), two to three feet wide."

This does

not correspond with any other report, or an existing example, of the Alaia.

Further consider ....

Given the reported length of an Olo (and Alaia) in this report is apprroximately 18 feet ("some three fathoms long"), then the technique of kicking ("impel") with the feet at take-off would appear highly inefficient and does not correspond to contemporary experience.

Details in the report on Trees and the Mode of Cutting deserve further consideration.

1. "The

uninitiated were naturally careless, or indifferent as to the method

of cutting the chosen tree."

Were the "uninitiated"

those not of the royal caste?

Were they a majority?

2. "The tree trunk was chipped away from each side until reduced to a board approximately of the dimensions desired (a billet), when it was pulled down to the beach and placed in in the 'halau' (canoe house) or other suitable place for its finishing work. "

billet - Crude timber or polyurethane foam block from which a board is shaped. Common usage ‘blank’.

Timber source ;

The comment

"it was pulled down to the beach" , is devoid of practical information.

As discussed below

the account does not indicate a required curing period either before of

after transportation.

The account of the

finishing process that follows does not indicate a curing or seasoning

period.

While cutting and

shaping the board from freshly cut green timber would be easier work, the

result would probably be a board prone to splitting and warping, as well

as being significanlty heavier than a cured board.

No available early surfboard building reference accounts for the need for a curing time.

For canoe construction,

Holmes

(1993)

notes...

"Menzies observes

that rough hewn canoes, 'after laying some time ... to season, were dragged

down in that state to the seaside to be finished ' ". Page 38.

Expanding on the process he adds...

"Usually the

log was left to season in a shaded place 'on logs to prevent it from

warping' , anywhere from several months to several years.

This served

to minimize the tendency of 'koa' to split, check or crack."

Page 40.

One would expect that successful surfboard construction would require an intial felling and rough shaping into a billet, followed by a a similar extended seasoning period.

3.

"Upon the selection of a suitable tree, a red fish called kumu was

first procured, which was placed at its trunk.

The tree was

then cut down, after which a hole was dug at its root and the fish placed

therein, with a prayer, as an offering in payment therefor.

Before using

the board there were other rites or ceremonies to be performed, for its

dedication.

As before,

these were disregarded by the common people, but among those who followed

the making of surf boards as a trade, they were religiously observed".

Although detailed

and explicit, Thrum's often quoted account of the required religious ceremony

closely resembles more detailed reports relating to canoe construction.

See Holmes

(1991), pages 30 to 42..

Certainly the report by "a native of the Kona district of Hawaii" is of a long past era', is it tainted by the more extensive formal ceremonies associated with the canoe builders?

And, were such reported ceremonial actives reserved only for craft that had specific cultural significance?

4. "The

tree trunk was chipped away from each side until reduced to a board approximately

of the dimensions desired ".

This corresponds

with most similar construction notes of the period, howerver some technical

considerations may have insight.

1. Shaping a board from a round log is a lot of work, although this would not be a major impediment to a skilled adzeman.

2. Such a method does result in a massive loss potentially valuable timber, producing a large pile of woodchips or shavings.

3. Canoe builders

selected trees that best replicated their intended designs, those with

bends or curves that allowed for the shaping of significant rocker into

the craft.

If surfboards were

built along the similar principles, then we would expect similar design

features to be exhibited in the surfboard design.

This assumes that

minimal rocker was not simply a design preference.

4. Indeed, if the

board was shaped from an individual log, there is no technical reason why

the design could not even include a keel or fin.

This assumes that

such a feature on the bottom would not be considered as significantly

increasing the potential danger - a reason given by some finless riders

in the 1940s.

Some pre-contact

paddle blades have small extensions on their tips (their pupose is unclear),

illustrating that such design features were possible.

"Thrum also noted a thanks-giving ritual in which a red fish called

kumu was buried among the roots of a tree selected and felled to make the

boards."

This is actually David Malo's 1840s account of canoe construction

(chapter 24), appropriated as an account of ancient surfboard construction

by Thrum's authors.

While there were some parallels, there are considerable differences

highlighted by several inconsistancies in Thrum's report.

As such, its accuracy is highly questionable.

5. If surfboard design and construction can be related to another Hawaiian maritime products, then it more closely resembles the production of paddles, rather than canoes.

My connention, based

only on cognitation, is that paddles and surfboards were probably shaped

from timber beams, split from logs using a combination of wedges, adzes

and hammers.

I would note that..

1. Splitting the

timber on site would greatly assist transport to the coast.

2. Splitting the

timber would maximise the timber available from a log.

3. Pre-contact boards

feature a minimal rocker (contrast canoes) that would appear to fall within

the parameters of a split beam.

4. Although I can

not confirm that Hawaiians used split timber in any other form of construction,

I am assuming that a technology that was able to split stone to construct

fine edged tools was also able to successfully split timber.

5. Split timber

would have a faster seasoning process, which may and allow a more regulated

loss of moisture producing a lighter board and a reduction in the tendency

for future splits or cracks.

6.Split timber would

be structurally stronger, improving potential board life.

A critcal point.

In describing the riding of the olo, Thrum states "This style was called

kipapa."

Pukui and Elbert's Hawaiian Dictionary (1986) defines kipapa as:

"nvi. Prone position on a surfboard; to asume such," page 154.

As the idea of the chiefs of Hawai'i riding their olo boards lying

down is somewhat at odds with modern perceptions, this rather inconvenient

statement appears has been overlooked by most (all?) commentators.

Given the olo board's narrow width, thickness, and domed deck, I think this is highly possible.

Background

and historical significance of KA NUPEPA KUOKOA

by Joan Hori,

Hawaiian Collection Curator,

Special Collections, Hamilton Library, University of Hawaiÿi at Mänoa

http://libweb.hawaii.edu/digicoll/nupepa_kuokoa/kuokoa_htm/kuokoa.html#intro

Answer to Mr. Thrum's letter of dismisal.

Thos. O. Thrum,

Registrar of Conveyances.

Sir: In view

of the charge you made against me as to my habit of reading newspapers

in office hours, allow me to explain.

...

Is it not a fact

that you have employed me, a government official, during office hours to

translate the following article for your

annual, viz.

Story of the

Menehune, Surf-riding, Canoe-making. Kuula-fish-god (First Part).

All of which

is now published, also the translation of the second part of the Kuula

story which is now in your possession, and not

paying for the

same as private work?

...

Respectfully

yours,

MOSES K. NAKUINA

Chronicling America

Evening bulletin.

(Honolulu [Oahu, Hawaii) 1895-1912, August 02, 1901, Image 6

Image and text provided

by University of Hawaii at Manoa; Honolulu, HI

Persistent link:

http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82016413/1901-08-02/ed-1/seq-6/

Note.

Also printed concurrently

in The Hawaiian Star, August 2, 1901, page 5.

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |