|

surfresearch.com.au

moerenhout : tahiti, 1834 |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

Moerenhout, J. A.:

Voyages Aux Iles Du Grand Ocean,

contenant des documents nouveaux sur la

geographie

physique et politique, la langue, la litterature,

la religion, les moeurs, les usages et les coutumes de leurs

habitants; et des considerations g?;n?;rales

sur le commerce, leur histoire et leur

gouvernement, depuis les temps les plus

recu?;s jusqu'a nos jours (two volumes in one).

Adrien Maisonneuve, Paris, 1944.

First edition 1959.

.

Reprint of the 1837 original, in two volumes.

J. A. Moerenhout was a merchant and diplomat travelled from Valparaiso, Chile at the end of 1828 to the Pacific islands, spending most of his onshore residence on Tahiti.

His book is not a published journal, but

rather a treatise composed following a return to France in 1834 and only

briefly quotes from journal entries.

As such, the chronology is difficult to

establish and Part II: Ethnography, (which

contains the surfriding report) is based on the totallity of Moerenhout's

readings and observations across Polynesia.

While the text does make several comparative

references to Hawaii (the Sandwhich Islands), Moerenhout does not specifically

record his landing there.

This may be indicated in the "Map drawn

by Moerenhout showing the routes of the three voyages", which although

listed as an illustrations as the Endplate (page ix) is not included in

the 1993 edition at hand.

The Hawaiian references may be derived

from Moerenhout's written sources.

The text certainly indicates the Moerenhout saw surfriding, however it is unclear if his observations were confined to Tahiti (the island of longest residence) or if surfriding was also noted on other islands.

The inclusive format adopted by Moerenhout in Part II would tend to imply the activity was widespread.

There are journal entries that record a visit to Matavai Bay, the anchorage of Wallis, Cook and Bligh that had been superceded by Papatee by the time of Moerenhout's arrival, and while not recorded as a location for surfriding, its exposure to summer swells is noted..

Also note that the author's preface notes

that Moerenhout had read "the works of the missionaries", including

the Rev. William Ellis who reported surfriding at Fare, Huahine circa 1820.

There are some similarities in the two

accounts.

Notes to the Author's

Preface.

...

The second will

present, under the title of Ethnography, all the remarks which my long

stay in these countries and my relations with the inhabitants have allowed

me to gather relative to their language, their religion, and their customs.

...

(Footnote) 4.

I had at my disposal scarcely anything more than the works of the missionaries,

some of which, it is true, offer interesting facts.

Mr. Ellis's,

among others, has often indicated to me most significant points of my research.

...

Paris, June 1835.

Page 16

Volume One

First Part

Chapter One

Section IV: Pitcairn

Island

...

Page 17

Notes from my

journal, 1829.

...

"It was noon when

I went down into the boat with one of the ship's officers, four sailors,

two natives, and an Englishman who had lived for five years at Pitcairn.

We sailed close

to the north-north-west coast.

On that day there

was a strong gust from the north, which could be felt even in our water;

the sea, rolling in long waves, also broke with such a din on the rocks

with which the island is surrounded on all sides that it seemed unapproachable

to us, even for the smallest boats.

We finally arrived

at the watering place, but without being able to make out the little bay

on account of the violence of the waves.

Then one of the

natives, a young man about twenty-five years old, six- ...

Page 18

... foot tall,

strong as Hercules, asked for the rudder, looked at the sea, and kept us

stopped for several minutes while several large waves went by, each in

turn raising our boat to its crest as if to break it with the wave on the

nearby rocks.

After having

three or four pass in that way, our young pilot, who hadn't stopped looking

out at the distance, all of a sudden cried: Now, now, pull away, pull!

and in less than nothing we found ourselves safe and sound in the little

bay."

"I had left the

boat, seeing around me only rocks almost like peaks, looking for some indication

of a route or some kind of path and not being able to find one, when I

heard the two islanders who accompanied us cry to the sailors: Save yourselves,

Save yourselves!, and, turning around, I saw a horrible wave of more than

twenty feet in height rollover them.

The natives held

the boat with a long rope.

Our sailors were

saved, but not without taking on part of the wave, which broke on the rock

with the noise of thunder, hit, them, and caused them to be swept away.

I was a witness

then of one of the most singular sights that I have seen in my life.

These two islanders,

fixing themselves on the rock with their sinewy arms, held the boat's rope,

looked calmly at the coming sea, and at a signal which they gave to each

other crouched down simultaneously to let the mass of water rollover them.

I believed them

to be lost when, a moment later, to my great astonishment, I saw them get

up as if nothing had happened, a maneuver which they repeated up to three

times; but then the sea, a little more calm, let them recall the sailors

and let them leave with the boat from that little bay, which they then

said was not safe on that day."

Page 23

"The boarding

boat waited for me.

One of the natives

again seized the helm to allow the boat to clear the pass, and as soon

as we were led out he wished us good day and jumped into the sea.

He swam in the

midst of waves and breakers with a skill which you would have to see to

get a true idea of, and in a few minutes we saw him safe and sound on land."

Page 54

Volume One

First Part

Chapter One

Section VI: Lord

Hood and Neighbouring Islands

Fragments from

my journal, 1829.

...

Page 55

...

February 29. -"A

strong current must have cast us to the west during the night because,

in spite of the superior maneuvering of the schooner and a good breeze,

in the morning we could scarcely gain the point where we had been yesterday.

At nine o'clock

we were in the north-east and at a little distance from the land.

I then embarked

in the small-boat, accompanied by three of the Pitcairn people, one of

whom held the rudder, and four sailors.

Four other Pitcairn

people were in their two little dugouts and were to land first in order

to receive our boat at the time when it would reach the reef, to draw it

more easily out of the middle of the breakers."

"In approaching

the land our pilot had the boat stop for more than a quarter of an hour,

not far from the reef, beaten by the sea with a rage which seemed not to

be going to let us land, while a number of enormous sharks surrounded our

boat, appearing to look at us as assured prey if the waves capsized us

or broke us on the rock.

The men in the

little dugouts had, however, already reached land and stayed on the reef,

ready to receive us.

Seizing a favorable

moment our pilot cried to the sailors to row, and finally carried by the

crest of a wave which took us at a frightful speed, we landed in a few

seconds on the reef, amid floods of foam."

...

Page 57

...

"That day was

spent in preparations.

About four o'clock,

when the schooner had got near the island, one of the dugouts was sent

aboard with fish.

I was always

astonished to see these men hazard themselves in those frail boats and

face the strongest wave at such a great distance from the land.

they showed themselves,

however, very calm, and they preferred them to the largest boats.

It is true that

they count much on their skill in swimming.

In spite of their

security I was never without fear, and was so much the more satisfied to

see them return since it was the two youngest of the troop who lad been

given the job."

Page 77

Volume One

First Part

Chapter Two

THE ARCHIPELIAN

ISLANDS.

...

Section I

Number I: The

Dangerous Archipelago

(Parata of the

Indians)

...

Page 78

The second general

observation to make on the inhabitants of the Dangerous Archipelago is

that they have been accepted from time immemorial as the hardiest navigators

of the area, by means of their large dugouts which often are more than

a hundred feet long and are built on a plan which makes them much resemble

our vessels because they have a keel, an interior timber work whose ribs

determine the form of the boat, and which, bearing on the keel, have deck

planks.

With these dugouts

they travel over the seas for several degrees around about; but as they

are too narrow for their length and their height, they attach two together,

and then, by means of the platform in the middle, they get in width at

least a third of their length.

They are pointed

at both ends, and they do not tack to change direction, but they turn the

sail and the rudder.

At Tahiti the

same boats are used for travel, but to build them they have need of the

inhabitants of the low islands.

They are called

pahi, a name which today designates our ships.

Page 82

Volume One

First Part

Chapter Two

Section I

Number III:

Two Groups and Neighbouring Islands

...

Page 85

...

March 8 (1829).

-"Yesterday morning I had noted how superior with respect to sight the

islanders were who had accompanied us.

They first saw

the island where Mr. Brock had landed.

At a distance

where it was impossible for us to distinguish anything they indicated to

us the precise point where that officer ocupied with the boat, and the

use of the telescope proved to us the exactness of their indications.

This morning,

in approaching the place where a fire was still burning, we were astonished

to see neither the boat nor our people.

The captain and

I took the telescope in turn, nothing; but our lndians, all at the same

time and without hesitation, pointed out to us the west of the island,

and what was our astonishment in directing the telescope to that point

actually to see the boat in the open sea, but so far away that it could

sarcely be discerned, even with the help of the instrument.

We steered Immediately

for it, and in less than a half hour our people were aboard."

Page 86

Volume One

First Part

Chapter Two

Section I: Pitcairn

IslandPart III

The Island Chain

and Neighbouring Islands

(Todos los Santos

of Bouchea; Anaa of the Natives)

...

Page 88

...

As for dugouts,

I saw them everywhere in different shapes and different sizes, but the

largest were those which they called pahi (ship) and which were used only

for long voyages at sea.

They have always

attached two together, with a platform in the middle.

These are immense

boats, one of which measured seventy-five feet long and twenty-eight wide.

They are built

on the same plan as our ships, with a keel, but rarely of a single piece,

and provided with ribs attached to the keel in a manner analogous to that

by which our builders nail the ribs of our ships.

Page 97

Part IV

Tiooka and Oura

(Taaroa and Taapouta

of the Indians) and the neighbouring islands.

...

Page 100

...

As soon as it

was light enough so that we could approach without danger, we steered toward

the island and skirted the southeast coast about six o'clock, but nowhere

did we see any trace of inhabitants or of divers.

To the south-west,

however, we saw five or six people together.

I myself then

went ...

Page 101

... the boat,

and when we got very close, I recognized that it was three men, two women

and a little boy, the only inhabitants of the island.

Since the sea

was too high to be able to land on the reef and the noise of the waves

did not allow us to be heard from that distance, I gave them a signal to

come, but they refused.

Then my servant,

born on the Marquesas, threw himself into the sea and, crossing the surf

by swimming, arrived on the reef in a few minutes, where he was covered

with caresses by the Indians, so gentle and simple when circumstances do

not make them depart from their true character.

Page 136

1832 (August)

Papara

....

Page 141

"Nearly a year

had passed and still no schooner.

We were in March,

had been advertised for me for December or for January.

I was now certain

that it was lost; what could I think of the extraordinarily delay of what

had been advertised?

The affair was

even more disturbing since from the nineteenth to the twenty-first of February

we had very rough weather during a Russian boat, the Crorky, under

Captain Haguemester, had almost been lost in the bay of Matavai.

These tempests,

sometimes very violent, announced themselves a little in advance."

Page 144

Article II

The Second Voyage

- 1832

...

Page 145

Before arriving

at Point Venus we drew back a distance from the coast because of a reef

which extends to the east of this point nearly two miles from land, being

the more dangerous in that it is still hidden under the water.

A whaling ship

had almost been lost there about two years before.

After having doubled

this point we again hugged the land, skirted the reef indicated in all

its north-west part by the waves which break over it continually.

We were close

enough to see Matavia distinctly and the bay where in 1766 Wallis came

to anchor, to the great astonishment of the islanders.

It was also in

this bay, or rather in this roadstead, that Cook cast anchor each time

he visited Tahiti.

On entering the

pass Wallis touched on a rock or part of the reef which he called Bolphin's

(sic, Dolphin) rock.

The reef exists

today and has scarcely increased since, which can be explained, in my opinion,

by its position in the center of the pass.

There is in fact

a continual current there occasioned by the river, quite large at this

spot, and by the sea water, which, dashed over the reef in all the eastern

part, returns to the sea following the pass of Matavai.

This unsafe bay

is used only by warships, which are in danger there from November to May.

I spoke in the

tale of my first voyage to Tahiti of the serious damage which the Russian

warship the Croky experienced there in 1830.

Page 316

Second Part:

Ethanography

Chapter Three

A.

Education

...

Page 318

... what pleased

them the most was to play in the water.

In that fiery

climate water was for them a second element, in which they spent at least

a quarter of their lives.

Scarcely had

it been born when the mother carried her child to the river, and from that

moment on until he could take care of himself she washed him several times

a day; as a result children in general knew how to swim almost as soon

as they knew how to walk.

Page 347

Chapter Three

Section III

Pleasures

Page 352

(Part ) III

General Festivities

(Taupitim or Oron)

Page 356

It was the areois

and the fatou note paupa which were most in favor and attracted the greatest

crowd, although in several places there were a great number of other diversions,

the principal ones of which were:

...

Page 357

...

4. The

fatiti achemo vaa, a dugout race.

This was the

favorite amusement of the inhabitants of Tongatabou and other Friendly

Islands, and the superior performance of their dugouts made them just as

formidable in sea fights as their swiftness in running in land battles.

Dugout races

were not the custom at all in the Society Islands, and they were not held

except in the great festivals and in the public merry-making.

For a purpose,

as in the foot races, they had some flag, which the victor took away.

All the dugouts,

whatever their size, could enter the contest, but never more than two at

a time, from the smallest paddled by only two persons, to the double dugouts,

which often had twelve to twenty.

Once the signal

for departure was given the rivals' craft were followed by a great number

of others, which had to keep behind them all the time; the people who were

in them uttered cries and tried to encourage them, each one the backer

of his side, along with the crowd, which kept on the shore or endeavored

to follow the direction of the dugouts in their course.

The tumult continued

to increase from the moment of their arrival, the moment in which a piercing

cry from the conquerors was heard and from all those on their side, which

they repeated up to three times, raising their arms and waving their flags

and other objects in the air.

These demonstrations

were repeated for each of the couples engaged in the contest; and from

the pleasure which they seemed to take in this amusement, it was astonishing

that it was not more generally extended.

In the Friendly

Islands the dugouts also met with sails.

These games were

so much the more brilliant in that they took place in a calm and serene

time and in that the spacious bays formed by the coral reefs which surrounded

all the islands were moreover natural bays, the most suitable in the world

for that type of exercise. (18, see page 373)

Page 359

There were still

a number of other common amusements, some of them daily, which didn't stop

them from devoting themselves to them during solemn festivities.

These were:

...

3. The

horoue or goroue,(19, see

page 373) which consisted in letting themselves be carried by the ocean

waves, keeping on the top.

The most agreeable

amusement for them of all those which had been created for the water.

For its theater

this exercise had openings in the reefs, places where the sea broke with

the greatest furor.

Among all the

feats or skills which men in different countries have succeeded in doing

I know of none which surpasses this one or which causes more astonishment

at first sight.

Generally they

have a plank ...

Page 360

... three to four

feet long with which they take to the sea at a certain distance, waiting

for the waves, diving under those which are not strong enough, and letting

several of them roll over their heads until a very high one comes along,

which cries from the spectators on the shore announce to them, always gathered

in great numbers along the shore.

Lying on their

plank they wait for their wave, and at the instant when it approached them

they give themselves a movement which lets them reach the crest, from which

they are seen immediately carried with the rapidity of an arrow towards

the shore, which you would think they would be thrown upon in tatters,

but when they are very close, a little movement returns them and gets them

to leave the wave, which at the same instant breaks with a crash on the

sand or on the rocks, while the Indian afloat, and without ever leaving

his plank, leaves while laughing to start his terrible play over again.

Men and women love this diversion with a furor and practice it from their

youngest years; some of them gain a skill which goes beyond all belief.

I have seen some

of them in very bad weather jump to their knees on their plank and hold

themselves so in equilibrium while the flood carries them with a terrifying

speed.

Page 373

Notes to Chapter

III

...

18. The inhabitants

of the Friendly Islands attached such an importance to the construction

of the dugouts intended to meet in these public contests that, after they

had been launched and tried out, those which did not respond to their expectations

and the speed of travel were immediately condemned and destroyed.

19. The g is pronounced as in Spanish.

|

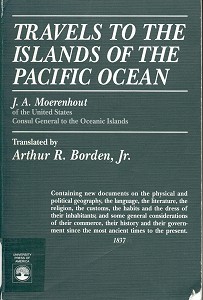

Travels to the Islands of the Pacific Ocean. Translated by Arthur R. Borden, Jr. University Press of America Inc. 4720 Boston Way, Lanham, Maryland, 0706. 3 Henrietta Street, London,WC2E 2LU England. 1993. Original French edition published 1837. |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |