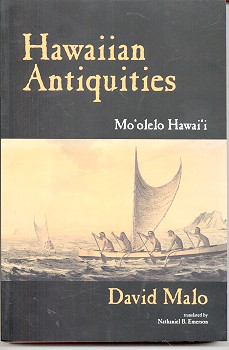

david malo : surfriding, 1840

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

surfresearch.com.au

david malo : surfriding, 1840 |

Originally writen

in native Hawaiian circa 1835-1840.

Translated from

the Hawaiian by Nathaniel B. Emerson, circa 1889.

Edited by W.D. Alexander

First published

1903.

Special Publication

2 Second Edition 1951.

Reprinted 1971,

1976, 1980, 1991, 1992, 1997, 2005.

Malo identifies surf

riding as "a national sport of the Hawaiians," and immediately refers to

its association with gambling and describes, rather unclearly, the format

of a surfing competition.

The translator,

Nathaniel B. Emerson (circa 1889), notes that interpreting the account

of the surfing contest was problematic.

Furthermore, at

the time of writing Malo was an enthusiastic Christian, and as Emerson

notes in his biographical sketch:

"his affections

were so entirely turned against the whole (Kapu) system, not only of idol-worship,

but all the entertainments of song, dance and sport as well, that his judgment

seems often to be warped."

As such, the reliability

of this passage is questionable.

Unfortunately, Malo's

estimation of surf board length, occassionally in excess of "four fathoms"

or 24 feet (1 fathom = 6 feet), begs credibility.

In the footnotes,

W.D Alexander (1903) was "inclined to doubt the accuracy" of Malo's statement,

and Tom Blake (1935) expressed similar reservations and suggested an alternative

calculation, "I believe Malo meant yards when he used fathoms."

That would suggest

a maximun board length at, a relatively conservative, 13 feet.

(Note that, apparently

without any evidence, Blake may have merely made the adjustment to make

his source appear more credible.)

Malo can be said

to accurately report that there were two different surfboard designs.

The first

were "broad and flat," later identified by I'li (1870) as the alaia,

and "generally hewn out of koa."

The second, "a narrower

board," later identified by I'li as the "thick" olo, "was

made from 'Wili'Wili.

Ellis (1825) had

also previously identified two surfboard designs, both "5 to 6 feet."

Some were "flat,"

but most were "slightly convex on both sides."

Willi willi as

a timber used to build surfboards, and their Hawaiian name, papa he'e

nalu.

The account of canoe

construction, in chapter 24, is particularly significant.

In 1896, the authors

(collectively refered to as Thrum) of an article titled Hawaiian Surfriding

appropriated much of this material as an account of ancient surfboard

construction.

While there were

some parallels, there are considerable differences highlighted by several

inconsistancies in Thrum's report.

1. Surf riding was a national sport of the Hawaiians, on which they were very fond of betting, each man staking his property on the one he thought to be the most skillful. (1)

2. When the bets

were all put up, the surf riders, taking their boards with them, swam out

through the surf till they had reached the waters outside of the surf.

These surf-boards

were made broad and flat, generally hewn out of koa. (2)

A narrower board,

however, was made from the wood of the 'Wili'Wili. (3)

3. One board would be a fathom in length, another two fathoms, and another four fathoms, or even longer. (4)

4. The surf riders

having reached the belt of water outside of the surf, the region where

the rollers began to make head, awaited the incoming of a wave, in preparation

for which they got their boards under way by paddling with their hands

until such time as the swelling wave began to lift and urge them forward.

Then they speeded

for the shore until they came opposite to where was moored a buoy which

was called a PUG.

5. If the combatants passed the line of this buoy together, it was a dead heat; but if one went by it in advance of the other, he was the victor.

6. "Ai ka au hou ana, O ka- mea i komo i ka pua hoomawaena mai oia, aole e hiki i ke kulana, O ka eo no ia nana; pela ka hee nalu." (5)

Page 223.

NOTES

ON CHAPTER 48

1. Sect. 1. Surf

riding was one of the most exciting and noble sports known to the Hawaiians,

practiced equally by king, chief and commoner.

It is still to

some extent engaged in, though not as formerly, when it was not uncommon

for a whole community, including both sexes and all ages, to sport and

frolic in the ocean the livelong day.

While the usual

attitude was that of reclining on the board face down-wards with one or

both arms folded and supporting the chest, such dexterity was attained

by some that they could maintain their balance while sitting or even while

standing erect as the board was borne along at the full speed of the inrolling

breaker.

Photographs can

be given in proof of this statement.

2. Sect. 2. Koa was wood of which the canoe was generally made.

3. Sect. 2. Wili-wili is a light, cork-like wood, used in making floats for the out-riggers of canoe, for nets, and a variety of other similar purposes.

4. Sect. 3. The

longest surf board at the Bishop Museum is sixteen feet in length.

It is difficult

to see how one of greater length could be of any service, and even when

of such dimensions it must have required great address to manage it.

It was quite

sufficient if the board was of the length of the one who used it.

One is almost

inclined to doubt the accuracy of David Malo's statement that it was sometimes

...

Page 224

... four, or even

more, fathoms in length.

If any thinks

it an easy matter to ride the surf on a board, a short trial will perhaps

undeceive him.

5. Sect. 6. I

am unable to give a satisfactory translation of this section.

It has been suggested

to me that the meaning is that the victory was declared only after more

than one heat, a rubber, if necessary. The Hawaiian text should be corrected

as follows:

..A i ka au hou

ana i ka mea i komo i ka pu-a i ho-o mawaena mai oia aole e hiki i ke kulana

0 ka eo ia nana.

Pela ka hee-nalu."

1. The Hawaiian

woo, or canoe, was made of the wood of the koa tree.

From the earliest

times, the wood of the bread-fruit, kukui, ohia-ha, and wiliwili was used

in canoe-making, but the extent to which these woods were used for this

purpose was very limited.

The principal

wood used in canoe-making was always the koa (Acacia heterophylla).

2. The building

of a canoe was an affair of religion.

When a man found

a fine koa tree he went to the kahuna kalai woo and said, "I have found

a koa tree, a fine large tree."

On receiving

this information, the kahuna went at night to the mua (1) to sleep before

his shrine, in order to obtain a revelation from his deity in a dream as

to whether the tree was sound or rotten.

3. And if in his sleep that night he had a vision of some one standing naked before him, a man without a malo or a woman without a pa-u, and covering their shame with the hand, on awakening the kahuna knew that the koa in question was rotten (puha), and he would not go up into the woods to cut that tree.

4. He sought another tree, and having found one, he slept again in the mua before the altar; and if this time he saw a handsome, well-dressed ...

Page 127

... man or woman standing before him when he awoke, he felt sure that the tree would make a good canoe.

5. Preparations

were made accordingly to go into the mountains and hew the koa into a canoe.

They took with

them, as offerings, a pig, cocoanuts, red fish (kumu), and awa.

Having come to

the place they camped down for the night, sacrificing these things to the

gods with incantations, (hoomana) and prayers, and there they slept.

6. In the morning

they baked the hog in an oven made close to the root of the koa, and after

eating the same they examined the tree.

One of the party

climbed up into the tree to measure the part suitable for the hollow of

the canoe, where should be the bottom, what the total length of the craft.

7. Then the kahuna

took the ax of stone and called upon the gods:

"0 Ku-pulupulu,

(2) Ku-ala-na-wao, (3) Ku-moku-halii, (4) Ku-ka-ieie, (5) Ku-palalake,(6)

Ku-ka-ohia-laka.(7)"

These were the

male deities.

Then he called

upon the female deities:

"0 Lea (8) and

Ka-pua-o-alakai, (9) listen now to the ax.

This is the ax

that is to fell the tree for the canoe. ..."

8. The koa tree was then cut down, and they set about it in the following manner: Two scarfs were made about three feet apart, one above and one below, and when they had been deepened, the chips were split off in a direction lengthwise of the tree.

9. Cutting in

this way, if there was but one kahuna, it would take many days to fell

the tree; but if there were many kahuna, they might fell it the same day.

When the tree

began to crack to its fall, they lowered their voices and allowed no one

to make a disturbance.

10. When the tree had fallen, the head kahuna mounted upon the trunk, ax in hand, facing the stump, his back being turned toward the top of the tree.

11. Then in a

loud tone he called out, "Smite with the ax and hollow the canoe! Give

me the malo!" (10)

Thereupon the

kahuna's wife handed him his ceremonial malo, which was white; and, having

girded himself, he turned about and faced the head of the tree.

12. Then having

walked a few steps on the trunk of the tree, he stood and called out in

a loud voice, "Strike with the ax and hollow it! Grant us a canoe !" (11)

Then he struck

a blow with the ax on the tree, and repeated the same words again; and

so he kept on doing until he had reached the point where the head of the

tree was to be cut off.

Page 128

13. At the place

where the head of the tree was to be severed from the trunk he wreathed

the tree with ieie (Freycinet-ia scandens).

Then having repeated

a prayer appropriate to cutting off the top of the tree, and having again

commanded silence and secured it, he proceeded to cut off the top of the

tree.

This done, the

kahuna declared the ceremony performed, the tabu removed; thereupon the

people raised a shout at the successful performance of the ceremony, and

the removal of all tabu and restraint in view of its completion.

14. Now began

the work of hewing out the canoe, the first thing being to taper the tree

at each end, that the canoe might be sharp at stem and stern.

Then the sides

and bottom (kua-moo) were hewn down and the top was flattened (hola).

The inner parts

of the canoe were then planned and located by measurement.

15. The kahuna

alone planned out and made the measurements for the inner parts of the

canoe.

But when this

work was accomplished the restrictions were removed and all the craftsmen

took hold of the work (noa ka oihana 0 ka ~)

.

16. Then the

inside of the canoe was outlined and the pepeiac, brackets on which to

rest the seats, were blocked out, and the craft was still further hewn

into shape.

A makuu (12)

or neck, was wrought at the stern of the canoe, to which the lines for

hauling the canoe were to be attached.

17. When the time

had come for hauling the canoe down to the ocean, again came the kahuna,

to perform the ceremony called pu i ka woo, which consisted in attaching

the hauling lines to the canoe log.

They were fastened

to the makuu. Before doing this the kahuna invoked the gods in the following

prayer:

"0 Ku-pulupulu,

Ku-ala-na-wao, and Ku-moku-halii! look you after this canoe. Guard it from

stem to stern until it is placed in the halau."

After this manner

did they pray.

18. The people

now put themselves in position to haul the canoe.

The only person

who went to the rear of the canoe was the kahuna, his station being about

ten fathoms behind it.

The whole multitude

of the people went ahead, behind the kahuna no one was permitted to go;

that place was tabu, strictly reserved for the god of the kahuna kalai

woo.

Great care had

to be taken in hauling the canoe.

Where the country

was precipitous and the canoe would tend to rush down violently, some of

the men must hold it back lest it be broken; and when it got lodged some

of them must clear it.

This care had

to be kept up until the canoe had reached the halau, or canoe house.

There are no points 19 or 20. (?)

Page 129

21. In the halau,

the fashioning of the canoe was resumed.

First the upper

part was shaped and the gunwales were shaved down; then the sides of the

canoe from the gunwales down were put into shape.

After this the

mouth (waha) of the canoe was turned downwards, and the iwi kaele (bottom),

being exposed, was hewn into shape.

This done, the

canoe was again placed mouth up and was hollowed out still further (kupele

maloko). The outside was then finished and rubbed smooth (ana.i ia).

The outside of

the canoe was next painted black (paele ia) .13

Then the inside

of the canoe was finished off by means of the koi-owili, or reversible

adz (commonly known as the kupa-ai kee).

22. After that

were fitted on the carved pieces (na laau) made of ahakea or some other

wood.

The rails, which

were fitted on to the gunwales and which were called moo (lizards), were

the first to be fitted and sewted fast with sinnet or ah'a.

The carved pieces,

called '1nanu, at bow and stern, were the next to be fitted and sewed on,

and this work completed the putting together of the body of the canoe (ke

kapili ana 0 ka waa).

It was for the

owner to say whether he would have a single or double canoe.

23. If it was

a single canoe (kaukahi) , cross-pieces (iako) and a float (ama) were made

and attached to the canoe to form the outrigger.

The ceremony

of lolo-u'aa, consecrating the canoe, was the next thing to be performed

in which the deity was again approached with prayer.

This was done

after the canoe had returned from an excursion out to sea.

24. The canoe

was then carried into the halau, where were lying the pig, the red fish,

and the cocoanuts that constituted the offering spread out before the kahuna.

The kahuna kalai

was then faced towards the bows of the canoe, where stood its owner, and

said, "Attend now to the consecration of the canoe (lolo ana 0 ka waa)

and observe whether it be well or ill done."

Then he prayed

(English

translation reproduced only):

That ax also is

a kuwa.

This is the ax

of our venerable ancestral dame.

Venerable dame!

What dame?

Dame Papa, the

wife of Wakea.

Page 130

She set apart

and consecrated, she turned the tree about,

She impelled

it, she guided it,

She lifted the

tabu from it.

Gone is the tabu

from the canoe of Wakea.

Ancestral dame!

What dame?

Dame Lea, wife

of Moku-halii.

She initiated,

she pointed the canoe,

She started it,

she guided it;

She lifted the

tabu from it.

Lifted was the

tabu from the canoe of Wakea.

Fat dripping

here,

Fat dripping

there.

Active art thou

Kane;

Active art thou

Kanaloa.

What Kanaloa

art thou?

Kanaloa the awa

drinker.

.4wa from Tahiti,

Awa from Upolu,

Awa from Wawau.

Bottle up the

frothy awa,

Bottle up the

well-strained awa. Praise be to the God in the highest

heaven (laau)

I

The tabu is lifted,

removed.

It flies away.

27 -28. When the

kahuna had finished his prayer he asked of the owner of the canoe, "How

is this service, this service of ours?"

Because if anyone

had made a disturbance or noise, or intruded upon the place, the ceremony

had been marred and the owner of the canoe accordingly would then have

to report the ceremony to be imperfect.

And the priest

would then warn the owner of the canoe, saying, "Don't you go in this canoe

lest you meet with a fatal accident."

29. If, however, no one had made a disturbance or intruded himself while they had been performing the lolo (17) ceremony, the owner of the canoe would report "our spell is good" and the kahuna would then say, "You will go in this canoe with safety, because the spell is good" (maikai ka 1010 ana).

30. If the canoe

was to be rigged as part of a double canoe the ceremony and incantations

to be performed by the kahuna were different.

In the double

canoe the iako used in ancient times were straight sticks.

This ...

(Page 131)

...continued to

be the case until the time of Keawe, (18) when one Kanuha invented the

curved iako and erected the upright posts of the para.

Page 132

NOTES ON CHAPTER 29 (Emerson/Alexander)

Page 133

#13. Sect. 21.

This Hawaiian paint had almost the quality of a lacquer.

Its ingredients

were the juice of a certain 'Euphorbia', the juice of the inner bark of

the root ...

Page 134

... of the kukui

tree, the juice of the bud of the banana tree, together with charcoal made

from the leaf of the pandanus.

A dressing of

oil from the nut of the kukui was finally added to give a finish.

I can vouch for

it as an excellent covering for wood.

<...>

4. The koa (2)

was the tree that grew to be of the largest size in all the islands.

It was made into

canoes, surf-boards, paddles, spears, and (in modern times) into boards

and shingles for houses.

The koa is a

tree of many uses.

It has a seed

and its leaf is crescent-shaped.

5. The ahakea

(3) is a tree of smaller size than the koa.

It is valued

in canoe-making, the fabrication of poi boards, paddles, and for many other

uses.

<...>

Page 21

<...>

12. The wili-wili

is a very buoyant wood, for which reason it is largely used in making surf

boards (papa-hee-tlalu), and outrigger floats (anuz) for canoes.

...

13. The ulu or

breadfruit is a tree whose wood is much used in the construction of the

doors of houses and the bodies of canoes.

Its fruit is

made into a delicious poi. (7)

<...>

13. The following

practices were considered hewa (wrong

conduct) by the landlord, that one should gjve himself up to the fascinations

of sport and squander his property in puhenehene, sliding the stick (pahee),

bowling the ulu- maika, racing with the canoe, on the surfboard or on the

holua sled, that one should build a large house, have a woman of great

beauty for his wife, sport a fine tapa, or gird one's self with a fine

malo.

All of these

things were regarded as showing pride, and were considered valid reasons

for depriving a man of his lands, because such practices were tantamount

to secreting wealth.

Canoes are rated

very highly after religious decorations or artifacts, points 7 and 8, pages

77 and 78.

This section does

not specifically include surfboards in its extensive list, unless they

are included in the general category...

Page 80

27. A great variety

of articles were manufactured by different persons which were esteemed

wealth.

|

Bernice P. Bishop Museum, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, Hawaii. Translated from the Hawaiian by Nathaniel B. Emerson, 1889. First published 1901. Special Publication 2 Second Edition 1951. Reprinted 1971, 1976, 1980, 1991, 1992, 1997, 2005. |

Malo was the son

of Aoao and his wife Heone, and was born at the seaside town of Keauhou,

North Kona Hawaii, not many miles distant from the historic bay of Kealakekua,

where Captain Cook, only a few years before, had come to his death.

The exact year

of his birth cannot be fixed, but it was about 1793, the period of Vancouver's

second visit to the islands.

Such good use did Malo make of his opportunties (at the Royal court) that he came to be universally regarded as the great authority and repository of Hawaiian lore.

As a natural result

of his proficiency in these matters, Malo came to be in great demand as

a raconteur of the old-time traditions, mele, and genealogies, as a master

in the arrangement of the hula, as well as of the nobler sports of the

Hawaiian arena, a person of no little importance about court.

In after years,

when his mind had been impregnated with the vivifying influence of the

new faith from across the ocean (Christianity), his affections were

so entirely turned against the whole system, not only of idol-worship,

but all the entertainments of song, dance and sport as well, that his judgment

seems often to be warped, causing him to confound together the evil and

the good, the innocent and the guilty, the harmless and the depraved in

one sweeping condemnation, thus constraining him to put under the ban of

his reprobation things which a more enlightened judgment would have tolerated

or even taken innocent pleasure in, or to cover with the veil of contemptuous

silence matters, which, if preserved, would now be of inestimable value

and interest to the ethnologist, the historian and the scholar.

Page iix

The date of Malo's removal to Lahaina, Maui, marks an important epoch in his life; for it was there he came under the inspiring influence and instruction of the Rev. William Richards, who had settled as a mis-

Page ix

sionary in that

place in the year 1823, at the invitation of the queen- mother, Keopuolani.

Under the teachings

of this warm-hearted leader of men, to whom he formed an attachment that

lasted through life, he was converted to Christianity, and on his reception

into the church was given the baptismal name of David.

There seems to

have been in Mr. Richards' strong and attractive personality just that

mental and moral stimulus which Malo needed in order to bring out his own

strength and develop the best elements of his nature.

...

From his first

contact with the new light and knowledge of Christian civilization, David

Malo was fired with an enthusiasm for the acquisition of all the benefits

it had to confer.

He made efforts

to acquire the English language, but met with no great success: his talents

did not lie in that direction; one writer ascribes his failure to the rigidity

of his vocal organs.

His mental activity,

which was naturally of the strenuous sort, under the influence of his new

environment seemed now to be brought to a white heat.

In his search

for information he became an eager reader of books; every printed thing

that was struck off at the newly established mission press at Honolulu,

or afterwards at Lahainaluna, was eagerly sought after and devoured by

his hungry and thirsty soul.

He accumulated

a library which is said to have included all the books published in his

own language.

In taking account

of David Malo's acquirements as well as his mental range and activity of

thought, it is necessary to remember that the output of the Hawaiian press

in those days, though not productive of the newspaper, was far richer in

works of thought and those of an educational and informational value than

at the present time.

It was pre-eminently

the time in the history of the American Protestant Mission to Hawaii when

its intellectual force was being directed to the production of a body of

literature that should include not only the textbooks of primary and general

education, but should also give access to a portion of the field of general

information.

It was also the

time when the scholars of the Mission, aided by visiting friends from the

South, were diligently engaged in the heavy task of translating the Bible

into the Hawaiian vernacular, the completed result of which by itself formed

a body of literature, which for elevation and excellence of style formed

a standard and model of written language worthy to rank with the best.

On the establishment

of the high school at I.,ahainaluna Lahaina, Maui, in 1831, Malo

Page x

entered as one of the first pupils, being at the time about thirty-eiglrt year!; of age, and there he remained for several years, pursuing the variou!; branches of study with great assiduity.

Page xi

While at Lahaina David Malo also occupied for a time the position of school-agent, a post of some responsibility and in which one could usefully exercise an unlimited amount of common sense and business tact; there also was the chief scene of his labors for the preservation in literary form of the history and antiquities of his people.

To confine one's

self to that division of David Malo's life-work which is to be classed

as literary and historical, the contributions made by him to our knowledge

of the ancient history and antiquities of the Hawaiian Islands may be embraced

under three heads: First, a small book entitled "Moolelo Hawaii," compiled

by Rev. Mr. Pogue from materials largely furnished by the scholars of the

Lahainaluna Seminary. (The reasons for crediting Malo with having lent

his hand in this work are to be found in the general similarity of style

and manner of treatment of the historical part of this book with the one

next to be mentioned. and still more conclusive evidence is to be seen

in the absolute identity of the language in many passages of the two books.)

Second, the work,

a translation of which is here presented, which is also entitled 'Moolelo

Hawaii', though it contains many things which do not properly belong to

history. The his- torical part brings us down only to the times of Umi,

the son of Liloa.

Page xii

The trustees of

the Bernice Pauahi [Bishop] Museum, by publishing Dr. N. B. Emerson's translation

of David Malo's Hawaiian Antiquities, are rendering an important service

to all Polynesian scholars.

It will form

a valuable contribution not only to Hawaiian archaeology, but also to Polynesian

ethnology in general.

It is extremely

difficult at this late day to obtain any reliable information in regard

to the primitive condition of any branch of the Polynesian race.

It rarely happens

in any part of the world that an alien can succeed in winning the confidence

and gaining an insight into the actual thoughts and feelings of a people

separated from himself by profound differences of race, environment and

education.

But here another

difficulty arises from the rapidity of the changes which are taking place

throughout the Pacific Ocean, and from the inevitable mingling of old and

new, which discredits much of the testimony of natives born and educated

under the new regime.

In the following work, however, we have the testimony of one who was born and grew up to manhood under the tabu system, who had himself been a devout worshipper of the old gods, who had been brought up at the royal court, and who was considered by his countrymen as an authority on the subjects on which he afterwards wrote.

His statements are confinned in many particulars by those of John Ii of Kekuanaoa, of the elder Kamakau of Kaawaloa, and of the historian, S. M. Kamakau, the latter of whom, however, did not always keep his versions of the ancient traditions free from foreign admixture.

Although David

Malo evidently needed judicious advice as to his choice and treatment of

subjects, some important topics having been omitted, and although his work

is unfinished, yet it contains materials of great value for the "noblest

study of mankind."

Its value is

very much enhanced by the learned notes and appendices with which Dr. Emerson

has enriched it.

The following

statement may serve to clear away some misapprehensions.

The first "Moolelo

Hawaii" (i. e., Hawaiian History), was writ-

Page xvii

(The first "Moolelo

Hawaii" (i. e., Hawaiian History), was writ-) ten at Lahainaluna

about 1835-36 by some of the older students, among whom was David Malo,

then 42 years of age.

They formed what

may be called the first Hawaiian Historical Society.

The work was

revised by Rev. Sheldon Dibble, and was published at Lahainaluna in 1838.

A translation

of it into English by Rev. R. Tinker was published in the H awaiian Spectator

in 1839.

It has also been

translated into French by M. Jules Remy, and was published in Paris in

1862.

The second edition of the Moolelo Hawaii, which appeared in 1858, was compiled by Rev. J. F. Pogue, who added to the first edition extensive extracts from the manuscript of the present work, which was then the property of Rev. Lorrin Andrews, for whom it had been written, probably about 1840.

David Malo's Life

of Kamehameha I, which is mentioned by Dr. Emerson in his life of Malo,

must have been written before that time, as it passed through the hands

of Rev. W. Richards and of Nahienaena, who died December 30, 1836.

Its disappearance

is much to be deplored.

W. D. ALEXANDER.

Page xiix

Preface

"Hawaiian antiquities,"

which was first published in 1903, has long been considered a classic because

it was written by a Hawaiian scholar whose early background was old Hawaiian,

whose later life was in- fluenced by missionary teaching and beliefs.

It has been out

of print for many years, during which the Museum has received innumerable

inquiries as regards a second edition.

Now, though the

Trustees have long felt it advisable to spend the Museum's limited printing

fund on original manuscripts rather than on the reprinting of old material,

the demands of the public and of anthropology students have prompted them

to approve a second edition.

At first, as

an economy measure, it was planned to make an offset reproduction of the

original, but through the generosity of the Honolulu Star-Bulletin we have

been able to reproduce the book by letter press at no greater cost than

that of the planographic method.

Page xix

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |