g. m. sproat : canoe riders of vancouver island, 1868

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

surfresearch.com.au

g. m. sproat : canoe riders of vancouver island, 1868 |

Internet Archive

http://archive.org/details/scenesandstudie01sprogoog

Herve noted:

"Sproat was businessman,

government agent, Indian reserve commissioner, magistrate, and author.

His book is an examination

of the Aht native tribe of Vancouver Island’s west coast, whom James Cook

had called Nootka."

In particular, Sproat

had a strong interest in ethnology, as evidenced by the footnote on page

85, where he makes reference to his paper published in Transactions

of the Ethnological Society in 1866.

One hundred and

fifty years before a theory of ancient coastal migration would gain some

scientific credence, Spoat does not doubt "whether savages could cross

in canoes from the Asiatic to the American shore."

For a recent compliation of scientific artcles supporting coastal migration

theory, see:

Bicho, Haws, and Davis (editors): Trekking

the Shore- Changing Coastlines and the Antiquity of Coastal Settlement

(2011).

To the south of Vancouver

Island, on 26th August 1912, the Tacoma Times reported a group of

day-vistitors traveled on the Northern Pacific Railway to Moclips Beach

in Washington where the various entertainments included "surf riding by

the Quinalt (sic) Indians."

The Quinault Indians

had developed a high degree of skill with canoes carved from cedar trees

in a variety of specialized designs adapted to

rivers, estuaries,

and the sea.

Moclips may be a

variation of the Quinault No-mo-Klopish, meaning “people of the

turbulent water.”

Also see:

1815 Peter Corney

: Hawai'i and Columbia River.

1835 Rev. Samuel

Parker : Native Canoe at

Columbia River.

1836 Washington Irving : Columbia

River Canoes.

Unfortunately, there

appears to be no accounts of the maritime skills of the native inhabitants

of California, their culture coming under severe pressure with the arrival

of Spanish missionaries in 1697.

By 1820 Spanish

influence was marked by the chain of missions occupying a 25 mile wide

coastal zone between Loreto, north to San Diego, to just north of today's

San Francisco.

-Wikipedia: History

of California to 1899, viewed 14 June 2013.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_California_to_1899

"Archaeological research has shown that San Miguel Island was first

settled by humans at least 12,000 years ago, in the Millingstone Horizon

archaeological period.

Because the northern Channel Islands have not been connected to the

adjacent mainland in recent geological history, the Paleo-Indians who first

settled the island clearly had boats and other maritime technologies.

Rough seas and risky landings did not daunt the Chumash people.

They called the island Tuquan in the Chumash language, and for several

centuries, they used plank-built canoes, called tomols, to reach their

settlements."

-Wikipedia: San

Migel Island- History, viewed 14 June 2013.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Miguel_Island

Herve also included

the identification of Irving (1836), above, and attached two illustrations

to his post.

The first,

W. de la Montagne Cary's Indian Canoe Race, published by Harper’s

Weekly in 1874, illustrates a paddling-while-standing technique

in bark-canoes..

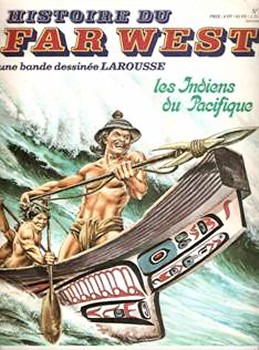

The second is Los

Indians de Pacifique, drawn by G. D’Antonio for the cover of a French

educative comic book, Histoire du Far West, published in 1982.

In this fanciful

represenation, a native prepares to launch his spear-harpoon while the

crew ster the canoe on a considerable wave.

Reproduced below.

During summer

they are much in the open air, lightly clad, and in winter pass most of

their time sitting round fires in a smoky atmosphere.

All the natives

swim well, but not so fast nor so lightly as Europeans; they labour more

in the water.

As divers they

cannot be beaten; a friend of mine saw Maquilla, a noted warrior and fisherman

of the Nitinahts, dive from the stern of a boat, in five fathoms of water,

and bring up a pup seal in each hand from the bottom.

On approaching

the boat, one of the seals got away, but Maquilla, throwing the other into

the boat, again dived and captured the seal before it could reach the bottom.

Till beyond middle

age many of the natives bathe every day in the sea, and in winter they

rub their bodies with oil after coming out of the water.*

[Footnote] * Throughout the year, though the climate on the whole is milder than the English climate, the water in the sea round Vancouver Island is colder than on any part of the shores of Great-Britain.

Page 36

I remember many

instances of Indians having escaped from us through their skill in swimming,

and paddling, and travelling through the woods.

The management

by a single Indian of a canoe in crossing a rapid stream cannot be surpassed.

At the same time,

I may observe that I have seen a trained crew of white men beat a crew

of Indians in a long canoe race on the sea. The civilized man seems to

have more bottom in him, when the exertion is intense and prolonged.

Page 65

The men have few out-door amusements except swimming, or trying strength by hooking little fingers, which is always conducted with good humour.*

[Footnote]* From some cause, perhaps the constant use of the paddle, their fingers are very strong ; as already stated, I have seen middle-sized natives carry heavy weights with their fingers which stalwart woodmen could scarcely lift.

Page 82 [CANOES]

Canoes are made

on this coast principally of cedar, and are well shaped, and managed with

great skill by men, women, and children.

They are moved

by a single sail or by paddles, or in ascending shallow rapid streams,

by long poles.

I have seen an

Indian boy with a single pole make good way with a small laden canoe against

a stream that ran at the rate of six miles an hour.

Canoes are of

all sizes, but of a uniform general shape, from the war-canoe of forty

feet long to the small dug-out in which children of four years old amuse

themselves.

Outriggers are

not used, but the natives sometimes tie bladders or

Page 83

seal-skin buoys

to the sides of a canoe to prevent it from upsetting in heavy weather.

The sail — of

which it is supposed, but rather vaguely, that they got the idea from Meares

some eighty years ago — * is a square mat tied at the top to a small stick

or yard crossing a mast placed close to the bow.

It is only useful

in running before the wind in smooth water.

The management

of a canoe by natives in a heavy sea is dexterous ; they seem to accommodate

themselves readily to every motion of their conveyance, and if an angry

breaker threatens to roll over the canoe, they weaken its effect quickly

by a horizontal cut with their paddles through the upper part of the breaker

when it is within a foot of the gunwale.

Their mode of

landing on a beach through a surf shows skill and coolness.

Approaching warily,

the steersman of the canoe decides when to dash for the shore; sometimes

quickly countermanding the movement, by strenuous exertion the canoe is

paddled back.

Twenty minutes

may thus pass while another chance is awaited.

At length the

time comes ; the men give a strong stroke and rise to their feet as the

canoe darts over the first roller ; now there is no returning : the second

roller is just passed when the bowpaddler leaps out and pulls the canoe

through the broken water ; but it is a question of moments : yet few accidents

happen.

The paddles

used by the Ahts are from four to five feet long, and are made of crab-apple

or yew.

Two kinds are

used ; the blade of one is shaped like a leaf, and the other tapers to

a sharp point.

The sharp-pointed

[Footnote] * Would it be fanciful to connect their first notion of a canoe sail with their observation of the membranous fan of the pine-seed, which they often see floating through the air, in the forest, after falling from the cones ?

Page 84 [MODE OF PADDLING.]

paddle is suitable

for steering, as it is easily turned under water.

It was formerly

used ag a weapon in canoe-fighting for putting out the eye — a disfigurement

which many of the old Aht natives show.

In taking a seat

in a canoe, the paddler drops on his knees at the bottom, then turns his

toes in, and sits down as it were on his heels.

The paddle is

grasped both in the middle and at the handle.

To give a stroke

and propel the canoe forward, the hand grasping the middle of the paddle

draws the blade of the paddle backwards through the water, and the hand

grasping the handle pushes the handle-end forward, and thus aids the other

hand in making each stroke of the paddle : a sort of double-action movement.

As a relief,

the paddler occasionally shifts to the handle the hand grasping the middle

of the paddle, and vice versa.

Such a position

looks awkward, but two natives can easily paddle a middle-sized canoe forty

miles on a summer day.

The Strait of

Juan de Fuca is about fifteen miles wide, and trading canoes often cross

during the summer season to the American

shore.*

The Indians paddle

best with a little wind ahead ; when it is quite calm, they often stop

to talk or look at objects in the water.

It is useless

to hurry them : they do quite as they please, and will sulk if you are

too hard upon them. In a small canoe, when manned by two paddlers,

[Footnote]* I

read with surprise the doubtful opinions of ethnological writers as to

whether savages could cross in canoes from the Asiatic to the American

shore.

The Aht natives,

and particularly the bolder Northern Indians, could do so in such canoes

as they now have without any difficulty. It is not easy to determine what

motive could induce savages to undertake such a voyage, or to migrate at

all over the sea.

The hope of reaching

a better country would not be likely to enter the mind of a savage.

He would not

move unless forced to move.

{See Paper by

G. M. Sproat in the Transactions of the Ethnological Society, 1866.)

Page 85 [MAKERS OF CANOES.]

one sits in the

stern and the other in the bow.

The middle is

the seat of honour for persons of distinction.

An Indian sitting

in the stem can propel and steer a canoe with a single paddle.

In crowded war-canoes

the natives sit two abreast.

No regular time

is kept in the stroke of the paddles unless on grand occasions, when the

canoes are formed in order, and all the paddles enter the water at once

and are worked with regularity.

The most skilful

canoe-makers among the tribes are the Nitinahts and the Klah-oh-quahts.

They make canoes

for sale to other tribes.

Many of these

canoes are of the most accurate workmanship and perfect design — so much

so that I have heard persons fond of such speculations say that the Indians

must have acquired the art of making these beautiful vessels in some earlier

civilized existence.

But it is easy

to see now, among the canoes owned by any tribe, nearly all the degrees

of progress in skilful workmanship, from the rough tree to the well-formed

canoe.

Vancouver Island

and the immediately opposite coast of the mainland of British Columbia

have always supplied the numerous tribes to the northward with canoes.

The native artificers

in these locahties have in the cedar (Thuja gigantea) a wood which

does not flourish so extensively to the north, and which is very suitable

for their purpose, as it is of large growth, durable, and easily worked.

Savages progress

so slowly in the arts, that the absence of such a wood as cedar, and the

necessity of fashioning canoes with imperfect implements from a hard wood

like oak, as the ancient people of Scotland did, might make a diflference

of many centuries in reaching a stated degree of skill in their construction.

Page 86 MODE OF MAKING CANOES.

The time for making

canoes in the rough is during the cold weather in winter, and they are

finished when the days lengthen and become warmer.

Few natives are

with-out canoes of some sort, which have been made by themselves, or been

worked for, or obtained by barter. The condition of the canoe, like an

Englishman's equipage, generally shows the circumstances of the possessor.

Selecting a good

tree not far from the water, the Indian cuts it down laboriously with an

axe, makes it of the required length, then splitting the trunk with wedges

into two pieces, he chooses the best piece for his intended canoe.

If it is winter,

the bark is stripped and the block of wood is dragged to the encampment

; but in summer it is hollowed out, though not finished, in the forest.

English or American

tools can now be easily procured by the natives.

The axe used

formerly in felling the largest tree, — which they did without the use

of fire — was made of elkhorn, and was shaped like a chisel.

Page 87

The making of

a canoe takes less time than has been supposed.

With the assistance

of another native in felling and splitting the tree, a good workman can

roughly finish a canoe of fifteen or twenty feet long in about three weeks.

Fire is not much

used here in the hollowing of canoes, but the outside is always scorched

to prevent sun-rents and damage from insects.

After the sides

are of the required thinness, the rough trunk is filled with fresh water,

which is heated by hot stones being thrown

into it, and

the canoe, thus softened by the heat, is, by means of cross-pieces of wood,

made into a shape which, on cooling, it retains.

The fashioning

is done entirely by the eye, and is surprisingly exact.

In nine cases

out of ten, a line drawn from the middle of the extremities will leave,

as nearly as possible, the same width all along on each side of the line.

To keep the canoe

in shape, light cross-pieces fastened to the inside of the gunwales are

placed

Page 88 [HOUSEHOLD UTENSILS.]

about four feet

apart, and there remain.

The gunwale is

turned outwards a little to throw off the water.

The bow and stern

pieces are made separately, and are always of one form, though the body

of the canoe varies a little in shape

according to

the capabilities of the tree and the fancy or skill of the maker.

Red is the favourite

colour for the inside of a canoe, and is made by a mixture of resin, oil,

and urine ; the outside is as black as oil and burnt wood will make it

; the bow and stern generally bear some device in red.

The natural colour

of the wood is, however, often allowed to remain.

The baling-dish

of the canoes is always of one shape — the shape of the gable-roof of a

cottage — and is well suited to its purpose.

Page 127 [COMPOUND WORDS]

We find the root

yat$ or yeU, which expresses the idea of movement of the feet or legs :

yetsook, is " to walk ; '* yetspannich, " to walk and see ; " yetshitl,

18 "to kick;'* and yetseh-yeUah (their only way of expressing either a

frequentative or plural being by

reduplication),

is " to kick frequently."

Yetseh-yet-sokleh,

undoubtedly from the same root, is a " screw steamer."

When the natives

first saw one of these vessels, noticing the disturbance of the water astern,

they attributed the propulsion to some action analogous to the stroke of

the legs of a swimmer, and so the name of "continual kicker" was at once

invented and universally received.

|

Scenes and Studies of Savage Life Smith, Elder and Co., London,1868. Internet Archive

|

|

W. de la Montagne Cary: Indian Canoe Race. Harper’s Weekly (1874). Right:

Cover of a French educative comic book, Histoire du Far West. Images forwarded

by

|

|

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |