|

surfresearch.com.au

a brief history of surfboard design |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

Their navigation skills took them

to the Solomon Islands, around 1600 BC, and later to Fiji and Tonga.

By the beginning of the 1st millennium

BC, most of Polynesia was a loose web of thriving cultures who settled

on the islands' coasts and lived off the sea.

By 500 BC Micronesia was completely

colonized.

Pre- Hawaii - Conjecture.

Exodus from Asia about....see

Debora

Smith (Science Editor) : Earth's first beachcombers ended up

in Australia.

Sydney Morning Herald : Weekend

Edition, May 14-15 2005 News : Page 13.

Reporting research developments published

in Science, 13 May 2005.

Initial migration by small groups across

small distances in crude craft.

Travell would be directed at observable

land masses, that is approximately 5 kilometres.

Craft could vary from a simple single

log to a timber raft.

As distances between islands became longer,

larger rafts would be required to carry larger numbers of passengers and

or supplies.

On occassion rafts could possibly be wind

driven by a simple square sail.

The development from this crude base to

sophisticated sailing canoes was concurrent with the use of a simple board

for personal transport over short distances.

The use of a small paddleboard was

to have two significant impacts on Polynesian culture....

1. It was adapted as a tool of recreation (exhilaration?) with the development of surfriding.

Shooting on a board and in a canoe

must have started further back than body shooting.

- Duke Kahanamoku, The Sun, Friday

8th January 1914.

Interview by W. F. Corbett.

At the start of the 20th century, the Polynesian

style (often mis-labeled the Australian Crawl) was becoming the

dominant competitive swimming stroke.

It was emphatically demonstrated by Duke

Kahanamoku's 1908 Stockholm Olympic performance.

By the end of the 20th century surfing had spread to across the world's oceans (and Lakes!) and surfing culture had global significance

Whatever it's primitive origins, by 400

A.D. when the first settlers reached Hawaii, five principles had been firmly

established...

1. wave riding is fun - the thrill of

the ride in is greater than the effort of the paddle out.

2. wave riding can be dangerous

3. the surfer must paddle in the same

direction as the wave to achieve take-off.

4. the ride is longer and faster if the

surfer rides diagonally across the wave face.

5. a rigid board will improve planning

and paddling - but can also increase the danger factor.

The origin of these boards is speculative, but broken sections from discarded canoes, outrigger floats or paddles (the blades) are possible sources.

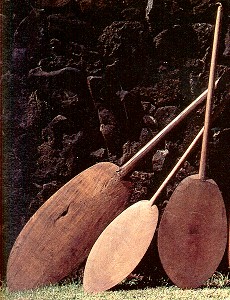

| Image right :

Hawaiian paddles, circa 1800. Bishop Museum Collection. Holmes (1993) page 59. The paddles (hoe) held by the Bishop

Museum have an average blade (laulau) length of 23 inches

and a width of 12 inches.

Note that the paddles were shaped from

on piece of timber and a broken shaft would render the paddle unusable.

See Holmes Chapter 7 : Paddles. |

|

With the development of an adult surfing

culture, prone boards became essential in acquiring basic surf skills.

In the 20th century, the Paipo has been re-invented several times

...

- the Surf-o-plane,

- the

Bellyboard,

- the Kneeboard,

- the Spoon,

- the Coolite

- the Mat,

and the most successful (in sales, performance and safety) Tom Morey's

Booggie

Board, 1971.

Further principles were established...

6. Width is limited to the width of the

ridder's shoulders.

8. The longer the board, the greater the

paddling speed.

9. The lighter the board the greater the

floatation

10. The nose is rounded and turned up

- for cutting and take off

11. The tail is wide and square.-

for maximum planning area and maximum safety.

12. Don't let go of the board.

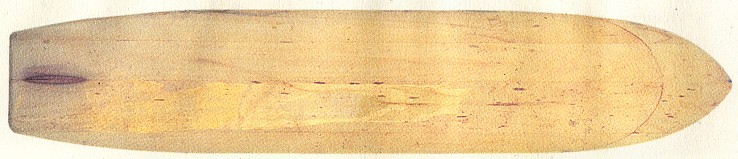

Dimensions vary between 6 feet and 12 feet in length, average 18 inches in width, and between half an inch and an inch and a half thick. The nose is round and turned up, the tail square. The deck and the bottom are convex, tapering to thin rounded rails. This cross-section would maintain maximum strength along the centre of the board and the rounded bottom gave directional stability, a crucial factor as the boards did not have fins.

Any discussion of the performance capabilities is largely speculation. Contemporary accounts definitely confirm that Alaia were ridden prone, kneeling and standing; and that the riders cut diagonally across the wave. Details of wave size, wave shape, stance and/or manouvres are, as would be expected, overlooked by most non-surfing observers. Most early illustrations of surfing simply fail to represent any understanding of the mechanics of wave riding. Modern surfing experience would suggest that high performance surfing is limited more by skill than equipment. It is a distinct probablity that ancient surfers rode large hollow waves deep in the curl - certainly prone, and on occassions standing.

By 1000 A.D these principles were confirmed...

13. Large waves are faster than small

waves.- a larger board is easier to achieve take off.

14. Steep waves are faster than flat waves.-

a smaller board is easier to control at take off.

15. Control is more important than speed

16. Surfboards are precious.

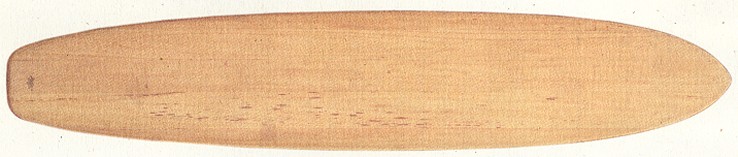

There are no contemporary accounts of how the boards were ridden, but it is most likely that the design was specifically for riding large swells on outside reefs, rather than on breaking or curling waves. In 1961, Tom Blake suggested that the Olo may have been ridden prone.

In the 1920's, Tom Blake and Duke Kahanamoku

reproduced the design in a hollowed version to radically reduce the

weight. See #5xx, below

Surfing's international status was boosted in October 1907 with publication in A Woman's Home Companion (of "A Royal Sport : Surfing at Waikiki" by Jack London. Jack London was a noted travel writer and the article was reprinted as a chapter in his book The Cruise of the Snark, 1911, His enthusistic instuctor was Alexander Hume Ford.

In California the exposure was more direct - George Freeth, considered one of the top riders, was commissioned to demonstate surfriding as a promotion for a land sale at Renaldo Beach in 1907. His enthusiasm and ability encouraged locals to take up the sport, and this was given further impetus with demonstations by Duke Kahanamoku in 1912, both on the West and East coasts. Duke Kahanamoku extended surfing's influence with visits to Australia and New Zealand in 1914-1915.

Surfing was limited to a very small number of native Hawaiians, but increasingly some Europeans became board riding enthusiasts. This was typified by the formation of the Outrigger Canoe Club by Alexander Hume Ford in 1908 at Waikiki. Ford enthusuiastically supported the traditional skills of surfboard riding and paddling outrigger canoes, and was Jack London's instructor.

To encourage young surfer's, entry fees were set at a minimum and boards were supplied for use or purchase ($2.00 in 1909). Developments continued with the appointment of Dad Center as Club Captain and the membership of Olympic swimmer Duke Kahanamoku in 1917.

The formation of the Outrigger Canoe

Club encouraged other surfing clubs, most noteably the Hui Nui whose members

included the Kahanamoku Brothers. Duke Kanhanmoku is credited with taking

the sport to new levels of performance and with developing the 10 ft board.

Using imported Californian redwood or sugar pine, he made thicker, wider

and longer boards to compensate for the lighter native timbers of traditional

boards. His basic design would be used around the world for the next 35

years.

This board successfully performed to Blake's expectactions, however the extreme weight was a major difficulty. His first experiment, hollowing out a solid board, had been attempted previously -

"As early as as 1918 Claude West

had experimented to make a hollow board, chippig and gouging out a solid

redwood slab and fitting a small sealed and screwed deck.

The experiment was not a success;

plywoods were not yet, nor plastic glues, timbers were sun dried intead

of kiln dried as now, and sun-cracks quickly gaped to let in water.

'Snowy' McAllister of Manly...also

experimented with chipped out boards.

He, too, was unsuccessful, though

he improved on the West model, also steamling the tail in the hope of gaining

more speed."

Maxwell

,

pages 239-240.

Probably similar attempts at hollowing

boards had been made by other surfers before Tom Blake...

however a combination of drilled holes

and extended curing made a noticable difference in weight

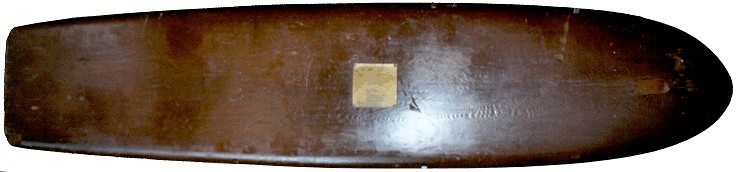

"This surfboard

was sixteen feet long and weight 120 pounds." Blake,

page 59

Blake also reported the length of this

board as 14 ft 6 inches in 1935, see above.

Nat Young personally interviewed Tom Blake

for his recollections of this period, published in 1983's The

History of Surfing, and although the length varies from Blake's

1935 notes, the account is detailed...

" He purchased a solid slab of redwood

16' long, 2' wide and 4" thick.

It weighed around 150 pounds - too

heavy to be of service as a surfboard, even when shaped.

So to lighten it he drilled hundreds

of holes in it from top to bottom, each hole removing a cylinder of wood

four inches long.

Then he left the holey board season

for a month.

After the wood had fully dried he

covered the top and bottom surfaces with a thin layer of wood, sealing

the holes. I

t finished up 15' long, 19" wide

and 4" thick, looking like a cigar.

It's weight was only 100 lbs, because

it was partly hollow."

Nat

History page 49

The second edition of History of Surfing (1994) is dedicated to Tom Blake who died May 5, 1994, aged 92.

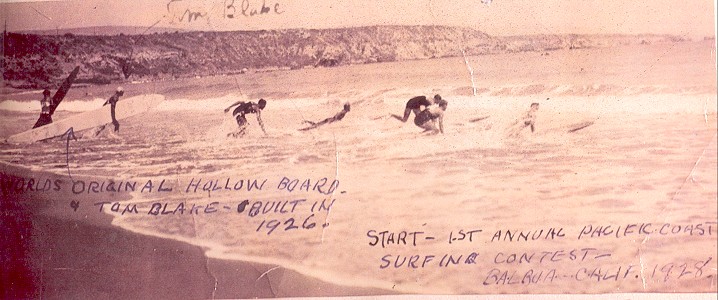

The complete photograph, see below,

notes a third length for this board of 14 ft 6 inches.

There is some confusion as to these board's

actual lengths.

It is possible that the board's length

was reduced between 1926 and 1930, due to modifications or repairs - it

certainly reduced in weight..

The board's paddling performance was demonstrated in 1928 when, after a slow start, Tom Blake emphatically won the 880 yards paddling race at the Pacific Coast Surfing Contest, Balboa, California. Blake, page 59.

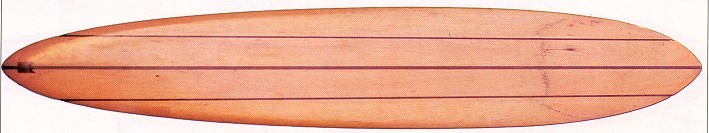

"In the later part of 1929, after

three years of experimenting, I introduced at Waikiki a new type

of surfboard;...but in reality the design was taken from the ancient Hawaiian

type of board, also from the English racing shell."

Blake,

page 51

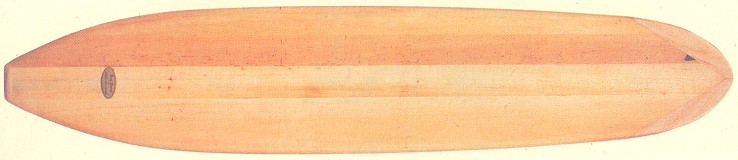

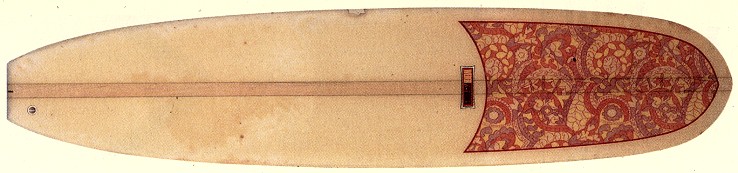

The template of this board was radically streamlined compared to it's predecessor.

The application of a light skin over a ridgid frame for boats dates back to the Irish chonicle or the Innuit kayak.

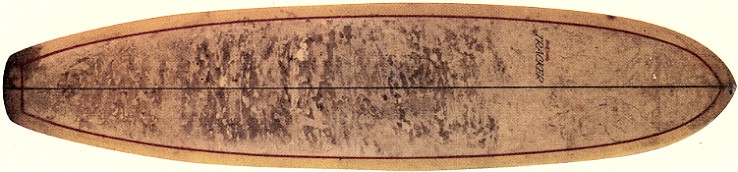

"It was called a 'cigar board', because

a newspaper reporter thought it was shaped like a giant cigar. This board

was really graceful and beautiful to look at, and in performance so so

good that officials of the Annual surfboard Paddling Championship immediately..."

Blake,

pages 51 - 52.

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |