|

surfresearch.com.au

glossary : surf-riding |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

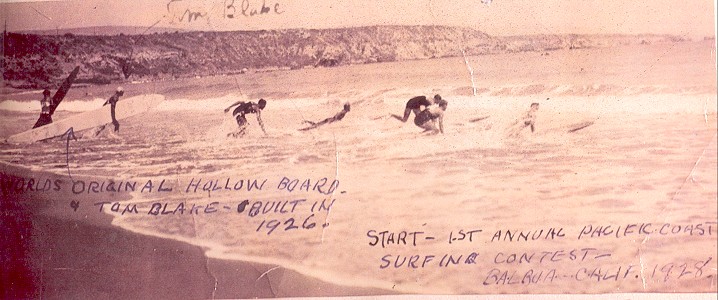

"In the later part of 1929,

after three years of experimenting, I introduced at

Waikiki a new type of surfboard;...but in reality the

design was taken from the ancient Hawaiian type of board,

also from the English racing shell."

Blake,

page 51

The template of this board was radically streamlined compared to it's predecessor.

The application of a light skin over a ridgid frame for boats dates back to the Irish chonicle or the Innuit kayak.

"It was called a 'cigar

board', because a newspaper reporter thought it was shaped

like a giant cigar. This board was really graceful and

beautiful to look at, and in performance so so good that

officials of the Annual surfboard Paddling Championship

immediately..."

Blake,

pages 51 - 52.

Worora youth on a mangrove tree raft (or 'kaloa'), George Water,

Western Australia, 1916

http://www.nma.gov.au/education-kids/classroom_learning/activities/basedow_photographs

Australian Aboriginal Canoes- Sydney

Compiled by Michael Organ

http://www.uow.edu.au/~morgan/canoes.htm

Aboriginal bark canoe, NSW

Stuart Humphreys © Australian Museum -

This is a bark canoe made in a traditional style from a sheet of

bark folded and tied at both ends with plant-fibre string.

The bow (the front) is folded tightly to a point; the stern (the

rear) has looser folds.

The canoe was made in 1938 by Albert Woodlands, an Aboriginal man

from the northern coast of New South Wales.

It measures 310 cm in length and 45 cm in width. E045964

- http://australianmuseum.net.au/image/Aboriginal-bark-canoe-NSW/

15. Dugong Hunting as Changing Practice: Economic engagement

and an Aboriginal ranger program on Mornington Island, southern

Gulf of Carpentaria

Cameo Dalley

http://epress.anu.edu.au/apps/bookworm/view/Indigenous+Participation+in+Australian+Economies+II/9511/ch15.html

2010, The global origins and development of seafaring /

edited by Atholl Anderson, James H. Barrett & Katherine V.

Boyle.

Cambridge : McDonald Institute of Archeological Research,

University of Cambridge ; Oakville, CT : David Brown Book Co.

[distributor], c2010.

2007, The history of seafaring : navigating the world's

oceans / Donald S. Johnson, Juha Nurminen.

London : Conway, 2007

http://trove.nla.gov.au/version/43515214

2003, The archaeology of seafaring in ancient South Asia

/ Himanshu Prabha Ray. Ray, Himanshu Prabha.

[To make a start I continue in the most general of terms but

specification of clear terms and definitions will be necessary

(fairly soon).]

Many popular works often assert that surfriding was invented by

the Hawaiian's, which in the narrow sense of "modern surfing," is

true.

However, there are reports of indigenous surfriding on the coasts

of Africa and India, with ample evidence across the islands of the

Pacific and it was common to Polynesia.

This suggests surfriding predates the Polynesian arrival in

Hawaii.

Futhermore, advance surfing skills may have been one of the

pre-requisites of exploration and colonisation of Polynesia.

The questions 'where' and 'when' are of interest; the answers are,

most probably, obscured in antiquity.

Many commentators acknowledge the similarities between body

surfing, canoe surfing, and surfboard surfing, and then attempt to

nominate the 'winner'.

Body surfing is usually relegated, with canoes or surfboards vying

for priority.

This may appear initially as classic example of 'which came first,

the dinosaur or the egg?'

In 1946, maritime historian. James Hornell provided a clear and

insightful answer- the first water craft was the log, or float

board, and the surfboard a very advanced development of this

most basic of vessels.

Hornell argues that the floatboard precedes its larger

derivations, the dug-out canoe and the raft, and was essential in

the development of swimming, the

By implication, it is probable that surfboard riding preceeded

canoe and body surfing.

Part One expands Hornell's thesis in examining the development of

the floatboard, swimming, dug-out canoes, and rafts from a

surfriding perspective.

2. The first recognised contribution to the history of surf

riding is Tom Blake' Hawaiian Surfboard (1935), but the

definitive work is Ben Finney's master's thesis, completed at the

University of Hawaii? in 1958?, which was published, in

conjunction with James Houston, as Surfing - The Sport of

Hawaiian Kings (1966).

The numerous historical sources identified by Finney have been

substantially expanded since 1966, and an intensive analysis of

these further broadens the subject.

Similarly, continuing developments in archelogy, anthropology and

genetics, also expand Finney's work.

Parts Two to Four examine Finney's three major elements of wave,

surfboard and surfrider.

Surfing - The Sport of Hawaiian Kings (1966).

The book wased based on , with two articles in the Journal

of Polynesia and one, in French, in the Journal?,

1959-1961?

The book was writen in conjunction with fellow surfer and

professional writer, James Huston, and published with a selection

of illustrations and photographs.

It was reprinted in 1966, with a new introduction, some different

photographs, and additional appendices.

A substantial portion of this paper is deeply indebted to Finney's

work, its scope and and content provide an established base from

which to analyse, criticise, and expand.

Part One

Some reflections on the nature of water.

Water is a bipolar molecule composed of hyrogen and oxygen that is

a liquid between 0 - 100 degress centigrade, and is essential for

the existance of carbon based life.

....

Psychologically,. still water presented humanoids with their

intial conception of their own image, albiet a "mirrored" version.

A true representation only became possible at the end of the 19th

century with the development of photography.

The word narcissm is often deemed applicable.

Part Two - The Wave.

Waves by Bascom

Part Three - The Surfboard

Finney on Surfboards

In several major aspects, this paper diverges from Finney's

(implied) assumptions.

Firstly, he states that "stand up surfing ... is the pinnacle of

the sport," and throughout the book, unless otherwise qualified,

surfing is riding upright on a surfboard.

This was not an unreasonable assumption in 1966, riding standing

on a 9-10 ft foam or balsa fibreglassed board with a fin was the

dominant form of the sport.

Since then ,the form and variety of surf-craft has vastly

expanded, currently the 9-10 ft board occupies only one

significant, but not dominant, segment of the craft that are

commonly called surfboards.

For example, Finney could not have seen the popularity of prone

surfing after the introduction of Tom Morey's Boogie board in the

1980s.

By overstating the significance of stand-up riding, Finney devalues the skill and performance of prone surfing and limits an appreciation of the potential of ancient Polynesian surf riders.

Hydronamic planning hulls by Lindsay Lord

Part Four - The Surfrider

the

act of riding – not white water!

Put in Blake & Finney references re 'sliding' XXX

hydrous– containing water

Includes

natural and mechanical standing waves, wave pools, boat wakes,

tidal bores, and wind generated waves on lakes, seas and

oceans.

without

craft – body surfing, incorporating arm and leg

power, occasionally utilizing body extensions.

Similar

behavior is also exhibited by other mammals, specifically

seals and dolphins.

Although usually for pleasure, efficient body surfing technique was a valuable skill for retrieving lost surfcraft in the era preceding the general adoption of the leg rope (US – surf leash), circa 1977.

Historically,

it is possible that body surfing and Polynesian swimming were

developed from board surfing

See Appendix A.

extensions – small appendages designed to improve body surfing performance, usually handboards and/or flippers (US – swim fins).

In the Modern era (circa 1950 - 1956), surfboard stability and performance was significantly enhanced with the addition of a structual extension - the fin.

various

craft – most designs have a single rider (personal

craft), but some have multiple riders.

Surfcraft

design must always considered relative to the available

materials and construction techniques.

propulsion

– when not riding the wave, the craft is either

physically powered by the rider/s (generally – ‘paddling’) or

with an outside power source.

The methods are

Arm and Leg power, Arm power only, Bladed Paddle power, Oar

power, Sail power and Motorized.

Propulsion is

necessary to advance the craft through the wave zone (‘getting

out’).

In general

surf-riding activity, most time is devoted to paddling

relative to the time actually spent riding the wave.

Getting out is

a variable function of the surf conditions and the rider’s

skill, and some craft are designed to excel at this aspect,

particularly those focused on rescue, competitive racing or

commercial applications.

Propulsion is

also necessary to achieve ‘take-off’.

The rider

‘takes off’ by positioning the board where the angle of the

wave face is steep enough for the board to achieve

planning velocity (= wave velocity).

Since personal

surf-craft cannot normally paddle faster than wave speed, this

is a critical calculation.

In this case,

the rider does not ‘catch’ the wave – rather the wave

‘catches’ the rider.

If there is a

sense in which the rider 'catches' the wave, then it is not as

in 'catching a ball' and more like 'catching a (moving)

train'.

As well as

paddling into position, by the rider maximising their paddling

velocity, the radical acceleration to wave velocity is

reduced.

For stand-up

surf-riders, the take-off is further complicated by the

radical change in position from prone to standing.

|

Finney and Houston (1966) Plate 23. |

Since we have no historical data on Ancient surf-riding performance, any comments on the early developments of surf-riding technique must be purely speculative.

Historically,

there appears to be a progressive development from the prone

to the standing position, accompanied by an increase in board

size..

These

developments can be classified as ...

Primitive

surf-riding - riding prone.

Traditional

surf-riding - riding in a variety of positions,

occassionally standing.

Classical

surf-riding - riding in a standing position.

Prone

The prone

position, by virtue of the proximity to the craft, allows

maximum control in extreme situations.

This reduces

the chance of separation from the craft and substantially

improves safety.

This was

critical before the universal adoption of the leg rope (US:

surf leash) circa 1974.

Prone boards

are basic tools for acquiring surf skills, particularly for

juvenile surfers.

Several

designers have enhanced the safety aspect of prone boards by

producing their designs in a “soft” format, for example

inflatable mats and the Boogie board.

Since the

1950’s many prone riders use extensions (flippers) to increase

paddle power and riding control.

The prone

position has the advantage of applying extra power by paddling

and/or kicking (the most effective) when the wave face becomes

less critical.

This option is

not readily available to standup riders.

When riding

the wave in the prone position the rider controls direction by

“loading up” either the left or the right leg.

Trim control is

achieved by reducing or increasing the leg drag.

Prone boards

were undoubtedly an essential evolutionary step in the

development of surf-riding and their use possibly pre-dates

body surfing.

See Appendix A.

The alternative possibility (McInnes, in conversation, 2001), that surf-riding was an extension from canoe surfing, seems unlikely given the use of bladed paddles, the seated riding position and considerable differences in riding technique and skills.

For successful

prone riding , the minimum board width probably has to be at

least six inches (hand-width) and the board shorter than body

length for the effective use of arm and leg power.

Wave riding at

this fundamental level of technique in this formulative

period may be descibed as Primitive surf-riding.

As previously

noted, surfcraft design must always considered relative to the

available materials and construction techniques.

Initially,

primitive board construction would be limited to the locally

available timber resources and construction was by hand tools.

These tools

were fashioned of stone, sometimes shell and often

mounted in a timber handle and secured wirh coconut sennit or

olona.

Coral was

available as an abrasive.

Despite the

stone-age tools, board builders were able to access the skills

and tecniques of the canoe builders.

The canoe

builders were the prime technological achievers of an

expanding maritime culture.

In a resource conscious community, it

is possible that some boards were fashioned from discarded

sections from damaged canoes, larger boards, outrigger floats or

paddles (the blades).

See Appendix B: Ancient Surf Board Construction

As a communal activity, there would

a 'communal quiver' of prone boards that would allow for their

performance to be critically assessed by different riders.

With a progression in riding

performance and construction techniques, and critically

assessment by community feedback, there were significant

incentives to build wider boards.

quiver - a collection of surfcraft, usually of one surf-rider, designed to be ridden in a range of surf-riding conditions.

Building wider boards requires only

a marginal adjustment in selecting from the available timber

resources.

Although a larger board is

potentially more dangerous, an increase in board width

substantially improves floatation and paddling.

Furthermore, on the wave face the

board planes earlier and the larger planning area reduces body

drag resulting in a longer and/or faster ride.

A wider board was also more stable,

and would encourage future experimentation in alternative riding

positions.

Note that for

personal surfcraft, width is limited to a maximum of

about 24''.

Widths above

24'' would be detrimental to efficient paddling technique.

See Blake (1935) in response toThrum's

(1896) reported widths of "two or three feet wide",

page 47.

Kneeling

(“Double Kneeling”)

The kneeling

position maintains a close proximity to the board, and has

moderate control in extreme situations.

Compared to the

prone position, there is some increased difficulty at take-off

because of the adjustment to the ridding position.

However,

kneeling improves the rider’s field of vision and allows the

rider alter the board’s centre of gravity significantly.

In an upright

position, board direction and trim is controlled essentially

by adjustments in body position, in considerable contrast to

the trailing legs of the prone rider.

Occasionally

the upright rider can initiate a “third point of stability”

(McTavish,1966) to adjust direction or trim, in the later case

usually to stall.

This can

variously be a hand drag (think Lopez), an arm drag (Reno), up

the extreme of the full body drag (Simon).

The 1960s

highly valued head dip may also qualify.

While many

writers report a technique of solid and hollow board riders

turning their boards by dragging their rear foot over the

inside rail, this was more likely a rare exhibition of great

skill.

A visualization

of doing this “backhand” approaches an athletic miracle.

Technically, a

board for successful knee riding must probably be at least

fourteen inches wide for an adult rider.

Boards 14

inches and wider invite the prospect of (limited) riding in

the standing position.

'Resolution'

midshipman George Gilbert (circa 1788), in the first report of

Hawiian surfboard dimensions gave the estimation of 6ft x 16''

with a 9'' tail and 4 1/2'' thick ...

"about

six feet in length, 16 inches in breadth at one end and

about nine at the other; and is four or five inches thick,

in the middle tapering down.'"

De

Vaga (ed, 2004) Page 15.

Regular success at riding in the kneeling position, would confirm the benefits of wider boards and tentative attempts at standing could have encouraged the production of longer boards and further increases in width.

Following the

Primitive era, the Traditional surf-riding

period is characterised by successfully riding in the

kneeling position, with the option to vary the riding position

depending on skill and the wave conditions.

For example

late prone take-off might be followed by kneeling through a

bumpy section, and then standing on the smaller smoother wave

that is closer to shore.

This

possibly equates with the state of surf-riding expertise

around Polynesian settlement of the Hawaiian Islands,

circa 400 - 600 C.E.

In the modern

era short and wide Kneeboards have been specifically designed

to be ridden in the kneeling position.

While

kneeboarders regularly use flippers to propel the board and

assist in take-off, when riding they are tucked under the

rider and play no role in maneuvering the board, apart to

severely restrict the rider to subsequently adjust their

position.

Occasionally,

Rescue or Paddle Boards are ridden in the kneeling position.

These riders

can, like prone and surf ski riders, increase propulsion if

the wave face flattens by using extra paddling strokes and the

technique can be critical in a competitive event.

Extra paddling

strokes, when riding, are used sometimes by kneeboarders, but

this is considered by surfriding aesthetes to be somewhat

lacking in style.

Drop-knee

Although a

specific riding position itself, the Drop-knee is an

essentially a transition positon that allows easy adjustment

from kneeling to either the standing or sitting

positions.

It was probably

a common technique in the period of boards without fins and

some early commentators imply the rider should initiate wave

direction in a prone or kneeling position before standing.

"This

finely-built Hawaiian, ... , caught the breaker he

wanted , and paddling along for a while

rose to

one knee first, then became gradually erect."

Corbett, W.

F. : "Wonderful

Surf Riding : Kahanamoku on the Board - A Thrilling

Spectacle"

The Sun

, Sydney: 24 th December 1914 . Page 6.

Some of Tom Blake’s water shots from the 1930’s show this technique.

The earliest

illustration of drop-knee is probably the cover illustration,

probably by Wallis McKay, of William Charles Stoddard’s Summer

Cruising in the South Seas (1874).

The work also

includes possibly one of the best early illustrations of

surfriding, a highly detailed image denoting several riding

positions, (sitting, drop-knee and standing, but not prone)

stance, duck-diving, waves in sets, off-shore winds and

significant wave height.

This image is reprinted in Lueras, Leonard: Surfing - The Ultimate Pleasure (1984) and the cover on page 50.

Critically

drop-knee surfers demonstrate an individual preference for the

raised leg, regardless of the riding direction, which is

replicated in the alternate standing positions of natural

(left-foot forward) and goofy (right foot forward).

The forward

positioning of the foot aligns the body along the board’s

longitudinal axis, whereas when prone the rider’s weight

(mass?) is distributed squarely across the board.

The dropped

rear leg (knee to toe) provides greater stability on the

board, compared to standing on both feet, and was sometimes

employed by 1960s board riders when negotiating a critical

section.

See Nat Young

at Collaroy photograph in Farrelly, Midget: This Surfing

Life (1965) page 37.

It is a recognised riding position by contemporary (finless) Boogie-board riders.

Sitting

The sitting

position is usually determined by the propulsion method.

These are

paddles (canoes, surfskis, kayaks), oars (surfboats, dorys) or

an motorised power source.

While

affording the same visual field as kneeling, adjustment of the

centre of gravity is limited.

Sitting is the most restictve

position from which to adjust or change the riding position.

For boards and

surf-skis, the position is intrinsically unstable in extreme

conditions.

Surfskis, from

the 1930's, improved control by the use of footstraps and in

circa 1969, Merv Larson in California added a seat belt to the

wave-ski.

On occasion,

the sitting position was used by traditional Hawaiian

surf-riders, see Wallis McKay's illustrations noted

above, and was occassionally used by longboard riders up

to the mid 1960s, its successful application considered a

demonstration of nonchalant skill.

Similar, but

more obscure, is the "Coffin ride".

Also from the

early1960s, it is initiated from the sitting position, whereby

the rider lays on their back with the head towards the tail.

Ideally, the

palms should be held on the chest, mimicking funereal ritual.

Standing

Standing

maximizes the rider’s field of vision and allows the rider

extreme body adjustment to the board’s centre of gravity.

The standing

position also entails the greatest risk of separation from the

board and an increase in danger.

This risk was

was vitually eliminated with the general adoption of the leg

rope (US – surf leash), circa 1977.

Stand-up surfing may have already been a recognised skill by Traditional surf-riders the time of Hawaiian settlement, but the subsequent developments led to a period where riding in the standing position was the dominant feature, Classic surf-riding.

On very rare

occassions, the rider can invert their position and firmly

gripping the rails, stand on their head.

Highly valued

as an example of skill in the early years of the twentith

century, the head stand is now considered an unfunctional

trick.

See photograph

Adrian Curlewis at Palm Beach circa 1935 in Maxwell

(1949) page ?

The biggest

determining factor in surfing performance appears to be the

rider’s skill, and although ‘designed’ to be ridden prone, the

earliest experiments at stand up surfing were probably on what

contemporary surf-riders would recognise as ‘prone or knee

boards'.

It is even

possible that the first experiments at stand-up surfing were

attempted as early as 2000 B.C.E., around the time of the

initial migrations into the Pacific.

|

Kuhio Pier, Waikiki, circa 1962 Photograph by Val Valentine Kelly, facing page 192. |

For Classic

surf-riders, the risk is greatest at take-off,

complicated by a radical change in position from prone to

standing.

This was

usually completed by a two stage process - first onto the

knees and then standing.

An alternative

method, placing one foot forward and balancing on the other

knee (in the Comtemporary era :'drop-knee style") was first

reported in 1912.

"This

finely-built Hawaiian, ... , caught the breaker he

wanted , and paddling along for a while

rose to

one knee first, then became gradually erect."

Corbett, W.

F. : "Wonderful

Surf Riding : Kahanamoku on the Board - A Thrilling

Spectacle"

The Sun

, Sydney: 24 th December 1914 . Page 6.

This alternative may be illustrated in some early Waikiki photographs.

XXX With the arrival in Hawaii, surf-riding development of suitable surf skills and the production of suitable boards, standing became a common riding position.XXXX

Experiments in stand-up surfing led to the development to two techniques, the early adoption of the Stance and a later refinement, the Spring.

The Stance

requires the rider to balance along, and not across, the

centre of the board.

Stance is

indicated by most of the earliest recognised images that

attempt to illustrate surf-riding.

It is not

reported in any of the early written accounts.

Classic

surf-riders are usually either Natural (left foot forward) or

Goofy (right foot forward).

Stance is not

determined by hand preference.

Personal

observation (no empicial data) indicates a ratio of

approximately 60/40 in favour of the Natural stance

surf-riders.

Early

surf-riding images illustrate both Natural and Goofy stances.

Goofy -

adj. 1. foolish or stupid. Macquarie Dictionary(1991).

Blake (1935) does not use the term and indicates

simply "left or right foot forward" - page 89

Muirhead

(1962) uses the term, page 51..

In the weakest

sense, the term has some implication of "not normal".

Also, perhaps a

stronger implication was mitigated by the character of a

popular cultural idenity, Goofy (Mickey Mouse's companion),

who appears in Walt Disney cartoons from circa 1936 to the

present.

There are

probaby cartoon images of Goofy surf-riding - I have no idea

if Goofy is a Goofy.

Stance is the defining characteristic of all the derivative board sports, (Skimboard?), Skateboard, Snowboard, Sailboard, Wakeboard and Kiteboard ; that trace their genesis to Classical surf-riding.

|

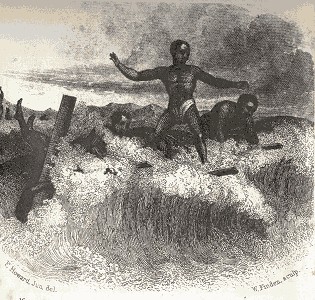

Illustration (etching) : F. Howard. The first reported Western image

of surf-riding, First

published in

|

This technique

is not reported by the earliest recognised commentators

on surf-riding.

They all seem

to indicate that standing followed an adjustment to the

kneeling position.

Blake

(1935) is possibly the earliest report of the spring as an

technique, page 89.

Note however

that in Blake's wave-story he recommends

standing up after turning the board and establishing the

slide.

wave story - a descriptive tale of the dynamics an individual wave and the rider's technique, usually an idealised case for instructional purposes.

Blake adds ...

"Some

prefer to stand up as soon as the wave is caught and steer

the board into that position. "

Given that

Blake is descibing riding boards without fins, this

'preference' would appear to require considerable skill and

was probably only empolyed by experienced riders.

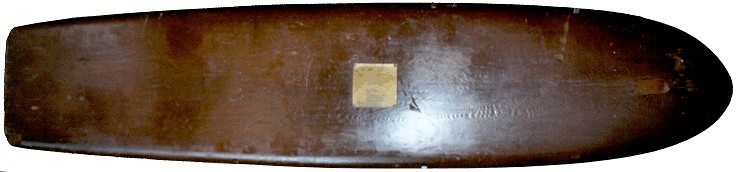

|

Photograph : Tom Blake First printed in National Geographic Magazine May 1935, page 598. Also Blake (1935), with alternative caption. between pages 32 and 33. |

The fin stabntially incresed stability of the new lightweight

construction

Other features

of Modern surfing include a significant increase in the angle

that a board can transverse the wave face.

This was of

particular annoyance to Bob Simmons, whose early designs

were constantly runnining over the, soon to be obsolete,

solid and hollow boards, that drew a much less radical angle.

It was possibly

even more annoying to those riders that the Simmons' crew ran

over.

Despite the

lightweight of the Malibu board, the significantly large

amount of drag provided by the fin made the board extremely

stable.

This ability

not only facilitated extreme adjustments to the centre of

gravity, but also allowed the rider to transverse the length

of the board.

usually for pleasure - mostly surf-riding is essentially for pleasure, but some craft and techniques have special rescue, competitive or commercial application.

By the end of the 20th century,

surf-riding and it's derivative board sports had global

significance.

“Shooting

on a board and in a canoe must have started further back

than body shooting”.

- Duke

Kahanamoku, Interview by W. F. Corbett,

The Sun,

Sydney, Australia, Friday 8th January 1914.

Tom Blake, citing conversations with Duke Kahanamoku, confirms that the 'Crawl' style was an integral part of successful body surfing technique and that it predates recorded history, Hawaiian Surfboard (1935), page 43.

"Duke

Kahanomoku calls attention to the fact that to catch a

wave for "body surfing," in the true Hawaiian manner, it

is necessary to swim before the breaker using the modern

crawl stroke, with a flutter kick.

As a boy,

Duke "body-surfed" and swam the crawl stroke before the

world had a name for it.

Also the

ancient Hawaiians, adapt at "body surfing," swam the crawl

stroke as part of the sport; therefore, the origin of the

so-called new crawl swimming stroke dates back to

antiquity."

In the following paragraph, Blake comes close to presenting a lineal connection between board paddling as a precursor for independent swimming based on a 'Crawl' technique.

"The crawl kick was also used in conjunction with the short three-foot surfboards used at Waikiki beach around the 1903 period."

At the start

of the 20th century, the Polynesian or Native style (often

mis-labeled the Australian Crawl) became the dominant

competitive swimming style, superceding the European

horizontally based Breast stroke and the developing Trudgeon

stroke.

In the 21st cetury, the Polynesian or Native style is used globally.

The report suggests further

consideration.

Firstly, although detailed and

explicit, Thrum's often quoted account of the required religious

ceremony closely resembles those also given for canoe

construction. (Holmes, 1991).

Where such reported ceremonial

actives reserved only for craft that had specific cultural

significance?

Certainly the report by "a native

of the Kona district of Hawaii" is of a long past era.

Thrum's, perhaps, more

realistic comments are usually given less weight by modern

commentators ...

"The uninitiated were naturally

careless, or indifferent as to the method of cutting

the chosen tree."

Were the "uninitiated" those not of

the royal caste, were they a majority?

2. Thrum a also infer that the board

was carved from a single log.

"The tree trunk was chipped

away from each side until reduced to a board approximately

of the dimensions desired (a billet), when it

was pulled down to the beach and placed in in the 'halau'

(canoe house) or other suitable place for its finishing

work. "

billet - Crude timber or polyurethane foam block from which a board is shaped. Common usage ‘blank’.

Thrum's account of the

finishing process that follows does not indicate a curing

period.

While cutting and shaping the board

from freshly cut green timber would be easier work, the result

would probably be a board prone to splitting and warping, as

well as being significanlty heavier than a cured board.

No available surfboard building reference accounts for the need for a curing time.

For canoe construction, Holmes

(1993) notes...

"Menzies observes that rough

hewn canoes, 'after laying some time ... to season, were

dragged down in that state to the seaside to be finished '

". Page 38.

One would expect that successful

surfboard construction would require an intial felling and rough

shaping into a billet, followed by an extended curing period.

Iron Age Observations

"perhaps oak to a desired width

and then making an even plank by using a tool such as a side

axe to remove excess timber would have achieved this. Split

timber is far stronger than sawn wood and would have been

more desirable as a structural material."

Phil Bennett : Bringing

Archaeology to Life: Reconstructing Iron Age Buildings

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/prehistory/ironage_roundhouse_03.shtml

Published: 01-07-2001

"The clencher method of

construction makes a hull very stiff for its weight and

requiring only the simplest tools to build it. An Axe,

wedges for splitting logs, a hammer for clenching nails and

a primitive bow drill are all that are necessary to

construct even the most advanced of the type, the Viking

Longship."

Michael Webb : Clinker Boat

History & Building

http://www.clinkerboat.com/about%20clinker%20boats.html

W.P. Armstrong

http://waynesword.palomar.edu/plsept99.htm

Wiliwili is an extremely upright growing nitrogen-fixing tree that is easily planted from leafless-and-rootless cuttings. Cuttings can be as small as one inch in diameter and one foot tall or as big as one foot in diameter and thirty feet tall or anywhere in between. Depending on what you're wanting to make out of wiliwili will determine what size cutting you choose.

So what can be made out of wiliwili? Here's an abridged list: living fences; fence posts for mounting metal fence or electic fence on; windbreak; posts for holding ridge poles for tarp structures; pin markers; mulch plants for fertilizing orchards and making compost; fodder for four-legged animals; famine food; bead making; etc.

Unlike most branching trees, wiliwili doesn't branch outward, it branches upward, so it maintains a clean compact shape no matter how old it gets. This makes it ideal for so many situations where a horizontally branching tree would get in the way - growing into paths, growing into structures, shading gardens or trees, etc.

Of course one of the best things about wiliwili is how easy it is to plant. Just cut a pencil point on the lower/fatter end of the cutting, shove it in the ground so it stands up and walk away! Over the next months it will start rooting and leafing out, and in less than a year you will have a fully-rooted fertility-factory. It can even be planted in 3 foot tall California Grass with almost no weeding or clearing and then eventually shade the area out, reducing/eliminating the California Grass.

So if you're designing a sustainable orchard and need mulch plants, or need a fast initial windbreak or hedge while your long-term, slower-growing plants mature, or want to build an eco-dwelling, or want to make a pasture and save money on fence posts, or, or, or then wiliwili is probably the plant for you. For hedges and windbreaks and mulch intercropping we recommend planting them on 2 - 3 foot centers in double rows on staggered spacing.

A final note: Wiliwili has very small thorns growing on it's bark. They're not big enough to cut, nor do they form slivers, but if you are handling them a lot or planting them you'll probably want to wear gloves. Otherwise you'll end up with scratches all over your hands. The scratches aren't deep enough to draw blood generally speaking, but they can be annoying for the next few days while they heal.

Gaia Yoga Nursery

http://www.gaiayoga.org/nursery/edible_tropical_plants.html

Last updated Wed, 12 Apr 2006

04:47:45 GMT

Latex: Breadfruit latex has been used in the past as birdlime on the tips of posts to catch birds. The early Hawaiians plucked the feathers for their ceremonial cloaks, then removed the gummy substance from the birds' feet with oil from the candlenut, Aleurites moluccana Willd., or with sugarcane juice, and released them.

After boiling with coconut oil, the latex serves for caulking boats and, mixed with colored earth, is used as a paint for boats.

Wood: The wood is yellowish or

yellow-gray with dark markings or orange speckles; light in

weight; not very hard but strong, elastic and termite

resistant (except for drywood termites) and is used for

construction and furniture. In Samoa, it is the standard

material for house-posts and for the rounded roof-ends of

native houses. The wood of the Samoan variety 'Aveloloa'

which has deeply cut leaves, is most preferred for

house-building, but that of 'Puou', an ancient variety, is

also utilized. In Guam and Puerto Rico the wood is used for

interior partitions. Because of its lightness, the wood is

in demand for surfboards. Traditional Hawaiian drums are

made from sections of breadfruit trunks 2 ft (60 cm) long

and 1 ft (30 cm) in width, and these are played with the

palms of the hands during Hula dances. After seasoning by

burying in mud, the wood is valued for making household

articles. These are rough-sanded by coral and lava, but the

final smoothing is accomplished with the dried stipules of

the breadfruit tree itself.

Purdue University : Center

for New Crops & Plant Products

Morton, J. 1987. Breadfruit. p.

50–58. In: Fruits of warm climates. Julia F. Morton, Miami,

FL.

http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/morton/breadfruit.html

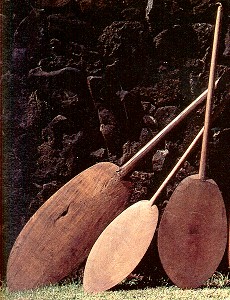

The origin of these boards is speculative, but broken sections from discarded canoes, outrigger floats or paddles (the blades) are possible sources.

| Image right : Hawaiian paddles, circa 1800. Bishop Museum Collection. Holmes (1993) page 59. The paddles (hoe)

held by the Bishop Museum have an average blade (laulau)

length of 23 inches and a width of 12 inches. Note that the paddles were

shaped from on piece of timber and a broken shaft would

render the paddle unusable. See Holmes Chapter 7 : Paddles. |

|

With the development of an adult

surfing culture, prone boards became essential in

acquiring basic surf skills. In the 20th century, the

Paipo has been re-invented several times ...

- the Surf-o-plane,

- the Bellyboard,

- the Kneeboard,

- the Spoon,

- the Coolite

- the Mat,and the most

successful (in sales, performance and safety) Tom Morey's

Booggie Board, 1971.

Further principles were

established...

6. Width is limited to the width of

the ridder's shoulders.

8. The longer the board, the greater

the paddling speed.

9. The lighter the board the greater

the floatation

10. The nose is rounded and turned up

- for cutting and take off

11. The tail is wide and

square.- for maximum planning area and maximum safety.

12. Don't let go of the board.

Dimensions vary between 6 feet and 12 feet in length, average 18 inches in width, and between half an inch and an inch and a half thick. The nose is round and turned up, the tail square. The deck and the bottom are convex, tapering to thin rounded rails. This cross-section would maintain maximum strength along the centre of the board and the rounded bottom gave directional stability, a crucial factor as the boards did not have fins.

Any discussion of the performance capabilities is largely speculation. Contemporary accounts definitely confirm that Alaia were ridden prone, kneeling and standing; and that the riders cut diagonally across the wave. Details of wave size, wave shape, stance and/or manouvres are, as would be expected, overlooked by most non-surfing observers. Most early illustrations of surfing simply fail to represent any understanding of the mechanics of wave riding. Modern surfing experience would suggest that high performance surfing is limited more by skill than equipment. It is a distinct probablity that ancient surfers rode large hollow waves deep in the curl - certainly prone, and on occassions standing.

By 1000 A.D these principles were

confirmed...

13. Large waves are faster than small

waves.- a larger board is easier to achieve take off.

14. Steep waves are faster than flat

waves.- a smaller board is easier to control at take off.

15. Control is more important than

speed

16. Surfboards are precious.

There are no contemporary accounts of how the boards were ridden, but it is most likely that the design was specifically for riding large swells on outside reefs, rather than on breaking or curling waves. In 1961, Tom Blake suggested that the Olo may have been ridden prone.

In the 1920's, Tom Blake and Duke

Kahanamoku reproduced the design in a hollowed version to

radically reduce the weight. See #5xx, below

Surfing's international status was boosted in October 1907 with publication in A Woman's Home Companion (of "A Royal Sport : Surfing at Waikiki" by Jack London. Jack London was a noted travel writer and the article was reprinted as a chapter in his book The Cruise of the Snark, 1911, His enthusistic instuctor was Alexander Hume Ford.

In California the exposure was more direct - George Freeth, considered one of the top riders, was commissioned to demonstate surfriding as a promotion for a land sale at Renaldo Beach in 1907. His enthusiasm and ability encouraged locals to take up the sport, and this was given further impetus with demonstations by Duke Kahanamoku in 1912, both on the West and East coasts. Duke Kahanamoku extended surfing's influence with visits to Australia and New Zealand in 1914-1915.

Surfing was limited to a very small number of native Hawaiians, but increasingly some Europeans became board riding enthusiasts. This was typified by the formation of the Outrigger Canoe Club by Alexander Hume Ford in 1908 at Waikiki. Ford enthusuiastically supported the traditional skills of surfboard riding and paddling outrigger canoes, and was Jack London's instructor.

To encourage young surfer's, entry fees were set at a minimum and boards were supplied for use or purchase ($2.00 in 1909). Developments continued with the appointment of Dad Center as Club Captain and the membership of Olympic swimmer Duke Kahanamoku in 1917.

The formation of the Outrigger

Canoe Club encouraged other surfing clubs, most noteably the Hui

Nui whose members included the Kahanamoku Brothers. Duke

Kanhanmoku is credited with taking the sport to new levels of

performance and with developing the 10 ft board. Using imported

Californian redwood or sugar pine, he made thicker, wider and

longer boards to compensate for the lighter native timbers of

traditional boards. His basic design would be used around the

world for the next 35 years.

This board successfully performed to Blake's expectactions, however the extreme weight was a major difficulty. His first experiment, hollowing out a solid board, had been attempted previously -

"As early as as 1918 Claude

West had experimented to make a hollow board, chippig and

gouging out a solid redwood slab and fitting a small sealed

and screwed deck.

The experiment was not a

success; plywoods were not yet, nor plastic glues, timbers

were sun dried intead of kiln dried as now, and sun-cracks

quickly gaped to let in water.

'Snowy' McAllister of

Manly...also experimented with chipped out boards.

He, too, was unsuccessful,

though he improved on the West model, also steamling the

tail in the hope of gaining more speed."

Maxwell

, pages 239-240.

Probably similar attempts at

hollowing boards had been made by other surfers before Tom

Blake...

however a combination of drilled

holes and extended curing made a noticable difference in

weight

"This

surfboard was sixteen feet long and weight 120 pounds."

Blake,

page 59

Blake also reported the length of

this board as 14 ft 6 inches in 1935, see above.

Nat Young personally interviewed Tom

Blake for his recollections of this period, published in 1983's

The

History of Surfing, and although the length varies

from Blake's 1935 notes, the account is detailed...

" He purchased a solid slab of

redwood 16' long, 2' wide and 4" thick.

It weighed around 150 pounds -

too heavy to be of service as a surfboard, even when shaped.

So to lighten it he drilled

hundreds of holes in it from top to bottom, each hole

removing a cylinder of wood four inches long.

Then he left the holey board

season for a month.

After the wood had fully dried

he covered the top and bottom surfaces with a thin layer of

wood, sealing the holes. I

t finished up 15' long, 19"

wide and 4" thick, looking like a cigar.

It's weight was only 100 lbs,

because it was partly hollow."

Nat

History page 49

The second edition of History of Surfing (1994) is dedicated to Tom Blake who died May 5, 1994, aged 92.

The complete photograph, see below, notes a third length

for this board of 14 ft 6 inches.

There is some confusion as to these

board's actual lengths.

It is possible that the board's

length was reduced between 1926 and 1930, due to modifications

or repairs - it certainly reduced in weight..

The board's paddling performance was demonstrated in 1928 when, after a slow start, Tom Blake emphatically won the 880 yards paddling race at the Pacific Coast Surfing Contest, Balboa, California. Blake, page 59.

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |