surfresearch.com.au

|

surfresearch.com.au

ballantyne : the coral island, 1858

|

R. M. Ballantyne : The Coral Island, 1858.

Ballantyne,

R.M.: The Coral Island.

Dean & Son, London.

circa early 1940s, Number 23 in the Dean's Classics'

series.

Originally published by

T. Nelson and Sons, London, 1858.

Introduction.

Ballantyne, R. M.

(Robert Michael), 1825-1894.

While

Ballantyne did not travel to the Pacific Islands before

writing The Coral Island, the text clearly indicates

that he read extensively on the subject before writing his

classic boy's adventure novel.

This would not

have been evident to most 19th century readers.

Wikipedia

notes: "...because of one mistake he had made in The

Coral Island, in which he gave an incorrect thickness

of coconut shells, Ballantyne would travel all over the

world to gain first-hand knowledge of his subject matter and

to research the backgrounds of his stories."

For his

account of Polynesian surfriding (page 175) he probably read,

at least, the published accounts of Cook's marineers in the

Hawaiian Islands (see Source Documents Hawai'i 1778 and Hawai'i 1789) and Rev.

Ellis' reports from Tahiti and Hawaii (see Source Documents Surf-riding in

the Society and Sandwich Islands).

In particular,

Ballantyne's remarks on swimming and diving (page 174) are

probably derived from Ellis.

It is also

evident that he read Charles Darwin's Journal and Remarks

1832-1835 (published 1839, commonly titled The

Voyage of the Beagle or Journal of Researches)

as Chapter XI's analysis of the volcanic formation of coral

islands has similarities with Darwin's ground breaking

research, see below.

CHAPTER XXV ...Native children's

games somewhat suprising...

Page 174

But the

amusement which the greatest number of the children of both

sexes seemed to take chief delight in was swimming and

diving in the sea, and the expertness which they exhibited

was truly amazing.

They seemed

to have two principal games in the water, one of which was

to dive off a sort of stage which had been erected near a

deep part of the sea, and chase each other in the water.

Some of them

went down to an extraordinary depth; others skimmed along

the surface, or rolled over and over like porpoises, or

diving under each other, came up unexpectedly and pulled

each other down by a leg or an arm.

They never

seemed to tire of this sport, and from the great heat of the

water in the South Seas, they could remain in nearly all day

without feeling chilled.

Many of

these children were almost infants, scarce able to walk; yet

they staggered down the beach, flung their round, fat little

black bodies fearlessly into deep water, and struck out to

sea with as much confidence as ducklings.

The other

game to which I have referred was swimming in the surf.

But as this

is an amusement in which all engage, from children of ten,

to grey-headed men of sixty, and as I had an opportunity of

witnessing it in perfection the day following, I shall

describe it more minutely.

I suppose

it was in honour of their guests that this grand

swimming-match was got up, for Romata came and told the

captain that they were going to engage in it, and begged him

to come and see."

"What sort

of amusement is this surf-swimming?" I inquired of Bill, as

we walked together to a part of the shore on which several

thousands of the natives were assembled.

"It's a very

favourite lark with these 'xtr'or'nary criters,"...

Page 175

... replied

Bill, giving a turn to the quid of tobacco that invariably

bulged out of his left cheek.

"Ye see,

Ralph, them fellows take to the water as soon a'most as they

can walk, an' long before they can do that anything

respectably, so that they are as much at home in the sea as

on the land.

Well, ye

see, I s'pose they found swimmin' for miles out to sea, and

divin' fathoms deep, wasn't exciting enough, so they

invented this game of swimmin' on the surf.

Each man and

boy, as you see, has got a short board or plank, with which

he swims out for a mile or more to sea, and then, gettin' on

the top of yon thunderin' breaker, they come to the shore on

the top of it, yellin' and screechin' like fiends.

It's a

marvel to me that they're not dashed to shivers on the coral

reef, for sure an' sartin am I that if any of us tried it,

we wouldn't be worth the fluke of a broken anchor after the

wave fell.

But there

they go! "

As he

spoke, several hundreds of the natives, amongst whom we were

now standing, uttered a loud yell, rushed down the beach,

plunged into the surf, and were carried off by the seething

foam of the retreating wave.

At the

point where we stood, the encircling coral reef joined the

shore, so that the magnificent breakers, which a recent

stiff breeze had rendered larger than usual, fell in thunder

at the feet of the multitudes who lined the beach.

For some

time the swimmers continued to strike out to sea, breasting

over the swell like hundreds of black seals.

Then they

all turned, and watching an approaching billow, mounted its

white crest, and each laying his breast on the short flat

board, came rolling towards the shore, careering on the

summit of the mighty wave, while they and the onlookers

shouted and yelled with excitement.

Just as the

monster wave curled in solemn majesty to fling its bulky

length upon the beach, most of the swimmers slid back into

the trough behind; others, slipping off their board, seized

them in their hands, and plunging through the watery waste,

swam out to repeat the amusement; but a few, who seemed to

me the most reckless, continued their career until they were

launched upon the beach, and enveloped ill the churning foam

and spray.

One of these

last came in on the crest of the wave most manfully, and

landed with a violent bound almost on the spot where Bill

and I stood.

I saw by his

peculiar head-dress that he was the chief whom the tribe ...

Page 176

...

entertained as their guest.

The

sea-water had removed nearly all the paint with which his

face had been covered, and as he rose panting to his feet, I

recognised, to my surprise, the features of Tararo, my oId

friend of the Coral Island.

CHAPTER XI ... Questions on the

formation of coral islands...

Page 76

Besides

this, I noticed that on the summit of the high mountain,

which we once more ascended at a different point from our

first climb, were found abundance of shells and broken coral

formations; which Jack and I agreed proved either that this

island mnst have once been under the sea, or that the sea

must once have been above the island.

In other

words, that as shells and coral ...

Page 77

... could

not possibly climb to the mountain-top, they must have been

washed upon it while the mountain-top was on a level with

the sea.

We pondered

this very much; and we put to ourselves the question, "What

raised the island to its present height above the sea?"

But to this

we could by no means give to ourselves a satisfactory reply.

Jack thought

it might have been blown up by a volcano; and Peterkin said

he thought it must have jumped up of its own accord!

We also

noticed, what had escaped us before, that the solid rocks of

which the island was formed were quite different from the

live coral rocks on the shore, where the wonderful little

insects were continually working.

They seemed,

indeed, to be of the same material - a substance like

limestone; but while the coral rocks were quite full of

minute cells in which the insects lived, the other rocks

inland were hard and solid, without the appearance of cells

at all.

Our thoughts

and conversations on this subject were sometimes so profound

that Peterkin said

we should

certainly get drowned in them at last, even although we were

such good divers! Nevertheless we did not allow his

pleasantry on this and similar points to deter us from

making our notes and observations as we went along.

R.M. Ballantyne: Wikipedia Bibliography

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Michael_Ballantyne

The Coral

Island: Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Coral_Island

|

|

Ballantyne,

R.M.: The Coral Island.

Dean & Son, London.

circa early 1940s, Number 23 in the Dean's

Classics' series.

Originally published by

T. Nelson and Sons, London,

1858.

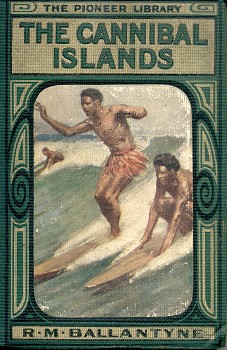

R.M. Ballantyne:

The

Cannibal Islands -

Captain

Cook's Adventures in the South Seas.

Nisbet

and Co. Ltd., 22 Berners Street, London, circa 1880.

Cover

paste down and Frontpiece.

"The Natives Playing in the

Water."

Artist

Unknown.

|

|

surfresearch.com.au

Geoff Cater (2009-2018) :

R.M. Ballantyne : The Coral Island, 1858.

http://www.surfresearch.com.au/1858_Ballantyne_Coral_Island.html