|

surfresearch.com.au

ellis : polynesian surf-riding, 1817-1823 |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

"Born in London of working class

parents in straightened circumstances, he developed a love of plants in

his youth and became a gardener, first in the East of England, then at

a nursery north of London and eventually for a wealthy family in Stoke

Newington.

Being of a religious nature, he

applied to train as Christian missionary for the London Missionary Society

and was accepted.

Ordained in 1815, he was posted

to the South Sea Islands with his wife, leaving England in 1816. They arrived

at Eimeo, one of the Windward Islands, via Sydney and learnt the language

there. During their stay there several chiefs of nearby Pacific islands

who had assisted Pomare in regaining sovereignty of Tahiti, visited Eimeo

and welcomed the LMS missionaries (including John Orsmond and John Williams

and their wives) to their own islands.

All three missionary families went

to Huahine , arriving in June 1818, drawing crowds from neighbouring islands,

including King Tamatoa of Raiatea.

In 1822, William Ellis went on elsewhere

in the Sandwich Islands but in 1825 had to return to England, Mrs Ellis

being in poor health, so took a ship via Hawaii and America."

WIKIPEDIA

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Ellis_(author)

Reference:

Ellis, John Eimeo and Allon, Henry: Life

of William Ellis.

1873.

1823 Tour

The first includes

a brief reference to

"playing in the surf"

- A Journal

of a Tour Around Hawaii, the Largest of the Sandwhich Islands

J.P. Haven and Boston

: Crocker, New York,. 1925. Page 65.

The fourth, published

in 1831, includes a narrative and the first known illustration of

surf-riding.

Dela

Vega (ed, 2004), pages 8, 18 and 19

Ellis may have

been influenced by Lt. King's

reports about surf-riding, first published in 1784, and there are some

close similarities in the accounts.

Strangely, Ellis'

description of the Hawaiians as "a race of amphibious beings" closely

corresponds to King's assesment, but only in the unedited version

(1967), to which we would assume, Ellis would not had access.

He was certainly

aware ot the work of fellow missionary, Charles Stewart.

Stewart's account

of surfriding was published by the same London publisher in 1829.

The two accounts

have some similarities, see Stewart

(1831).

Stewart's work includes

an account in Chapter XI of A Visit to Mr. and Mrs. Ellis,

Pages 232-233?

The Fifth Edition

(Enlarged) of 1839 includes an "Inroduction by the Rev. William

Ellis, from the London Edition'.

Ellis's account is

a finely considered appraisal, probably based on examining the activity

on a number of occasions.

He notes the preference

for selecting a specific location that is most suited to riding and certainly

witnessed the activity in excellent conditions.

This may not always

have been the case for some early accounts of surf-riding.

In assessing early

commentaries, it should be considered that if the reporter had enquired

about the suitability of the conditions, the reply might had included

a remark that translated as approximately "You should have been here yesterday

!".

Early accounts may

also have been restricted by viewing from shore.

Like Lt. King, it

is possible that on occassion, Ellis may have observed the activity from

a boat on the water.

If there were native

Hawaiians surf-riding in large and extreme surf conditions many metres

from the shoreline during the early 19th century, then is unlikely that

this activity could be intelligibly observed and recorded by European visitors.

Waimanu "bird

- water", is located on the north coast of the large island,

Hawai'i.

Finney

and Houston (1999) pages 28 and 29.

William Ellis' report is a trove of detailed description that covers many of the recognised technical features of surf-riding.

Page 223.

(Fare, Huahine, 1817-1822)

Like the inhabitants

of most of the islands of the Pacific, the Tahitians are fond of the water,

and lose all dread of it before they are old enough to know the danger

to which we should consider them exposed.

They are among

the best divers in the world, and spend much of their time in the sea,

not only when engaged in acts of labour, but when, following their amusements.

One of their

favourite sports is the 'horue' or 'faahee', swimming in

the surf, when the waves are high, and the billows break in foam and spray

among the reefs.

Individuals of

all ranks and ages, and both sexes, follow this pastime with the greatest

avidity.

They usually

selected the openings in the reefs, or entrances of some of the bays, for

their sport ; where the long heavy billows of the ocean rolled in unbroken

majesty upon the reef or the shore.

They used a small

board, which they called 'papa fahee' -swam from the beach to a

considerable distance, sometimes nearly a mile, watched the swell of the

wave, and when it reached them, resting their bosom on the short flat pointed

board, they mounted on its summit, and, amid the foam and spray, rode on

the crest of the wave to the shore: sometimes. they halted among the coral

rocks, over which the waves broke in splendid

confusion.

When they approached

the shore, they slid off the board which they grasped with the hand, and

either fell behind the wave, or plunged toward the deep, and allowed it

to pass over their heads.

Sometimes they

were thrown with violence ...

Page 224.

... upon the beach,

or among the rocks on the edge of the reef.

So much at home,

however, do they feel in the water, that it is seldom any accident occurs.

I have often

seen, along the border of the reef forming the boundary line to the harbour

of Fa-re, in Huahine, from fifty to a hundred persons, of all ages, sporting

like so many porpoises in the surf, sometimes mounted on the top of the

wave, and almost enveloped in spray; at other times plunging beneath the

mass of water that has swept in mountains over them, cheering and animating

each other; and, by the noise and shouting they made; rendering the roaring

of the sea, and the dashing of the surf, comparatively imperceptible.

Their surf-boards

are inferior to those of the Sandwich Islanders, and I do not think swimming

in the sea as an amusement, whatever it might have been formerly, is now

practised so much by the natives in the south, as by those in the north

Pacific.

Both were exposed

in this sport to one common cause of interruption; and this was, the intrusion

of the shark. The cry of a 'mao' among the former, and a 'mano' among the

latter, is one of the most terrific they ever hear; and I am not surprised

that such should be the effect of the approach of one of these voracious

monsters.

The great shouting

and clamour which they make, is principally designed to frighten away such

as may approach.

Notwithstanding

this, they are often disturbed, and sometimes meet their death from these

formidable enemies.

(At Waimanu, 1823)

As we crossed

the head of the bay, we saw a number of young persons swimming in the surf,

which rolled with some violence on the rocky beach.

To a spectator

nothing can appear more daring, and sometimes alarming, than to see a number

of persons splashing about among the ...

Page 369

...waves of the sea as they dash on the shore; yet this is the most popular and delightful of the native sports.

There are perhaps

no people more accustomed to the water than the islanders of the Pacific;

they seem almost a race of amphibious beings. (1)

Familiar with

the sea from their birth, they lose all dread of it, and seem nearly as

much at home in the water as on dry land.

There are few

children who are not taken into the sea by their mothers the second or

third day after birth, and many who can swim as soon as they can walk.

The heat of the

climate (2) is, no doubt, one source of the gratification they find in

this amusement, which is so universal, that it is scarcely possible to

pass along the shore where there are many habitations near, and not see

a number of children playing in the sea.

Here they remain

for hours together, and yet I never knew of but one child being drowned

during the number of years I have resided in the islands.

They have a variety

of games, and gambol as fearlessly in the water as the children of a school

do in their play-ground.

Sometimes they

erect a stage eight or ten feet high on the edge of some deep place, and

lay a pole in an oblique direction over the edge of it, perhaps twenty

feet above the water; along this they pursue each other to the outermost

end, when they jump into the sea.

Throwing themselves

from the lower yards, or bowsprit, of a ship, is also a favourite sport,

but the most general and frequent game is swimming-in the surf. (3)

The higher the

sea and the larger the waves, in their opinion the better the sport. (4)

On these occasions they use a board, which they call 'papa hi naru' [papa he'e nalu], (wave sliding-board,) generally five or six feet long, and rather ...

Page 370

... more than

a foot wide, sometimes flat, but more frequently slightly convex on both

sides. (5)

It is usually

made of the wood of the erythrina (6), stained quite black, and preserved

with great care. (7)

After using,

it is placed in the sun till perfectly dry, when it is rubbed-over with

cocoa-nut oil (8), frequently wrapped in cloth, and suspended in some part

of their dwelling-house.

Sometimes they

choose a place where the deep water reaches to the beach, but generally

prefer a part where the rocks are ten or twenty feet under water, and extend

to a distance from the shore, as the surf breaks more violently over these.(9)

When playing

in these places, each individual takes his board, and, pushing it before

him, swims perhaps a quarter of a mile or more out to sea. (10)

They do not attempt

to go over the billows which roll towards the shore, but watch their approach,

and dive under water, allowing the billow to pass over their heads. (11)

When they reach

outside of the rocks, where the waves first break, they adjust themselves

on one end of the board, lying flat on their faces, and watch the approach

of the largest billow; they then poise themselves on its highest edge,

and, paddling as it were with their hands and feet (12), ride on the crest

of the wave, in the midst of the spray and the foam, till within a yard

or two of the rocks or the shore; and when the observers would expect to

see them dashed to pieces, they steer with great address between the rocks

(13), or slide off their board in a moment, grasp it by the middle, and

dive under water (14), while the wave rolls on, and breaks among the rocks

with a roaring noise, the effect of which is greatly heightened by the

shouts and laughter of the natives in the water.

Those who are

expert frequently change their position ...

Page 371

...on the board,

sometimes sitting and sometimes standing erect in the midst of the foam.

(15)

The greatest

address is necessary in order to keep on the edge of the wave: for if they

get too far forward, they are sure to be overturned; and if they fall back,

they are buried beneath the succeeding billow. (16)

Occasionally they

take a very light canoe; but this, though directed in the same manner as

the board, is much more difficult to manage.

Sometimes the

greater part of the inhabitants of a village go out to this sport, when

the wind blows fresh toward the shore, and spend the greater part of the

day in the water. (17)

All ranks and

ages appear equally fond of it.

We have seen

Karaimoku and Kakioeva, some of the highest chiefs in the island, both

between fifty and sixty years of age, and large corpulent men, balancing

themselves on their narrow board, or splashing about in the foam, with

as much satisfaction as youths of sixteen. (18)

They frequently

play at the mouth of a large river, where the strong current running into

the sea, and the rolling of waves towards the shore, produce a degree of

agitation between the water of the river and the sea that would be fatal

to a European, however expert he might be; yet in this they delight: and

when the king or queen, or any high chiefs, are playing, none of the common

people are allowed to approach these places, lest they spoil their sport.

(19)

The chiefs pride

themselves much on excelling in some of the games of their country; hence

Taumuarii [Kaumuali'i], the late king of Tauai [Kaua'i], was celebrated

as the most expert swimmer in the surf, known in the islands. (20)

The only circumstance

that ever mars their pleasure in this diversion is the approach of a shark.

When this happens,

though they sometimes fly in every direc- ...

Page 372

... tion, they

frequently unite, set up a loud shout, and make so much splashing in the

water, as to frighten him away.

Their fear of

them, however, is very great; and after a party return from this amusement,

almost the first question they are asked is, "Were there any sharks?" (21)

The fondness

of the natives for the water must strike any person visiting their islands:

long before he goes on shore he will see them swimming around his ship;

and few ships leave without being accompanied part of the way out of the

harbour by the natives, sporting in the water; but to see fifty or a hundred

persons riding on an immense billow (22), half immersed in spray and foam,

for a distance of several hundreds of yards together, is one of the most

novel and interesting sports a foreigner can witness in the islands.

Page 373

Kukui (Candle nut)

Large quantities

of kukui, or candle nuts, hung In long strings in different parts

of Arapai's dwelling. These are the fruit of the 'aleurites triloba';

a tree which is abundant in the mountains, and highly serviceable to the

natives.

It furnishes

a gum, which they use in preparing varnish for their tapa, or native cloth.

The inner bark

produces a permanent dark-red dye, but the nuts are the most valuable part;

they are heart-shaped, about the ...

Page 374

... size of a

walnut, and are produced in abundance.

Sometimes the

natives burn them to charcoal, which they pulverize, and use in tatauing

their skin, painting their canoes, surf-boards, idols, or drums; but they

are generally used as a substitute for candles or lamps.

When designed

for this purpose, they are slightly baked in a native oven, after which

the shell, which is exceedingly hard, is takeu off, and a hole perforated

in the kernel, through which a rush is passed, and they are hung up for

use, as we saw them at this place.

When employed

for fishing by torch light, four or five strings are enclosed in the leaves

of the pandanus, which not only keeps them together, but renders the light

more brilliant.

When they use

them in their houses, ten or twelve are strung on the thin stalk of the

cocoa-nut leaf, and look like a number of peeled chesnuts on a long skewer.

The person who

has charge of them lights a nut at one end of the stick, and holds it up,

till the oil it contains is consumed, when the flame kindles on the one

beneath it, and he breaks off the extinct nut with a short piece of wood,

which serves as a pair of snuffers.

Each nut will

burn two or three minutes, and, if attended, give a tolerable light.

We have often

had occasion to notice, with admiration, the merciful and abundant provision

which the God of nature has made for the comfort of those insulated people,

which is strikingly manifested by the spontaneous growth of this valuable

tree in all the islands; a great convenicnce is hereby secured, with no

other trouble than picking up the nuts from under the trees.

The tree is large,

the leaves and wood remarkably white; and though the latter is not used

by the Sandwich Islanders, except occasionally in ...

Page 374

... making fences,

small canoes are frequently made of it by the Society Islanders.

In addition to

the above purposes, the nuts are often baked or roasted as an article of

food, which the natives eat with salt.

The nut contains

a large portion of oil, which, possessing the property of drying, is useful

in painting; and for this purpose quantities are carried by the Russian

vessels to their settlements on the north-west coast of America.

Sandal-wood Transport

Page 397

Before daylight

on the 22d, we were roused by vast multitudes of people passing through

the district from Waimea with sandal-wood, which had been cut in the adjacent

mountain for Karaimoku, by the people of Waimea, and which the people of

Kohala, as far as the north point, had been ordered to bring-down to his

storehouse on the beach, for the purpose of its being shipped to Oahu.

There were between

two and three thousand men, carrying each from one to six pieces of sandal

wood, according to their size and weight.

It was generally

tied on their backs by bands made of ti leaves, passed over the shoulders

and under the arms, and fastened across their breast.

When they had

deposited the wood at the store-house, they departed to their respective

homes.

Dela

Vega et. al (2004), page 18, notes:

"page 65. Mentions

the heiau 'Pakiha'...when the King was playing in the surf...'

Does not contain

the chapters and descriptions of the Narrative", noted

below.

2. Narrative of

a Tour of Hawaii, or Owhyhee,with Remarks on the History, Traditions, Manners,

Customs and Language of the Inhabitants of the Sandwich Islands.

H. Fisher &

Son./ P. Jackson, London, 1825-1826.

Second Edition 1827.

Five editions by 1929.

Dela

Vega et. al (2004), page 18, notes the surfing content at "pp. 276-8."

3. Polynesian

Researches, During a Residence of Nearly Six Years in the Society and Sandwich

Islands, Volumes I to III.

Jackson, Fisher

& Son & Co., London, 1829.

Dela

Vega et. al (2004), page 18, notes

"vol I, pp. 223,

305. Ellis descr!bes surf riding in Tahiti and compares them to Hawaiians.

(Quotation)

Noted the Tahitian

surf God was named Huaouri.

Does not include

Hawaiian text."

The second edition

by Jackson, Fisher & Son & Co., London,1831, (Enlarged and Improved)

is available online at googlebooks.com

http://books.google.com/books?id=G-QBtVplc-UC&pg=PA1&dq=William+Ellis

4. Polynesian

Researches, During a Residence of Nearly Eight Years in the Society and

Sandwich Islands, Volumes I to IV..

Fisher, Son and

Jackson, London, 1831.

Dela

Vega et. al (2004), page 19, notes

"vol. IV, pp.

368-72. Hawaiian surfing text from the Narrative.

This edition

introduces, on its title page (See on pg. 8) the first published drawing

of a man standing on a surf- board, by F. Howard.

Both Narrative

and Polynesian Researches have been reprinted several times, and

many do not have the surfing content and etching."

Volume IV published

separately in 1969:

Ellis, Rev.

William: Polynesian Researches: Hawaii

A New Edition, Enlarged

and Improved

Charles E. Tuttle

and Company

Rutland, Vermont

and Tokyo Japan,1969.

Introduction by

Edourad R. L. Doty, 471 pages.

Fourth printing

1979.

Surfriding text

pages 368 - 372.

Surfriding illustration

frontpiece, fold-out map.

Ellis' acount of Surfriding at Waimanu

is reproduced in:

Finney, Ben and

Houston, James D. : Surfing

– A History of the Ancient Hawaiian Sport. 1996.

Appendix C. Pages

98 to 99.

The illustration by F. Howard is reproduced

on the frontpiece.

5. The American Mission in the Sandwich

Islands: A Vindication and an Appeal, in Relation to the Proceedings of

the Reformed Catholic Mission at Honolulu.

1866.

Hosted by the University of Michigan Digital

Library.

http://www.hti.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=moa;idno=AGA4516

|

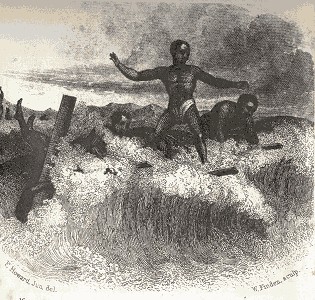

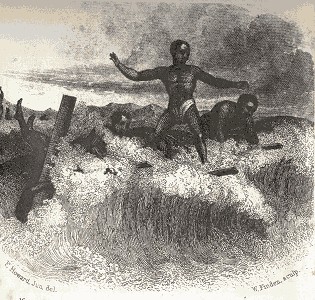

The first reported Western image of surf-riding, it correctly identifies Stance. (23) Illustration (etching) : F. Howard. First published

in

|

2. "The heat

of the climate ..."

The benign weather

conditions of the hawaiian islands were an undoubted contibution to the

development of surf-riding.

In the Modern era,

the general availablity of wetsuits would allow surf-riders to expand their

activity to worldwide climates.

3. " ... the

most general and frequent game is swimming in the surf."

Notes that suf-riding

is the recreation activity of primary significance to Hawaiian culture.

4. "The higher

the sea and the larger the waves, in their opinion the better the sport."

The appeal of the

challenge of extreme conditions confirms Lt.

King's observation, see Notes 5.1.

5. "... a board,

... generally five or six feet long, and rather more than a foot wide,

sometimes flat, but more frequently slightly convex on both sides."

A brief but explicit

description of the average board dimensions and features.

this correponds

with most other early accounts and with examples held by collectors.

See Alaia,

circa 1865.

6. "... erythrina,"

Wiliwili

(Erythrina sandwicensis)

... Although

harder than balsa, the native Hawaiian coral tree called wiliwili also

has a very soft, light wood.

In fact, it

was highly prized by Hawaiians for the outriggers of their traditional

canoes.

Because of

its buoyancy, it was also used for surfboards and fishnet floats.

7. "...

stained

quite black, and preserved with great care."

This confirms later

reports that detail some of the ancient construction techniques.

See Thrum (1896)

: Hawaiian

Surf-riding.

8. "After using

... rubbed-over with cocoa-nut oil."

This probably acts

a timber preservative that helps to prevent the board from taking

water.

Not a reported,

but theoretical proposition - the water repulsion characteristics of the

cocoa-nut oil may have assisted the the rider's grip on the board, similar

to the role of parrafin wax in the modern

era.

9. "... generally

prefer a part where the rocks are ten or twenty feet under water, and extend

to a distance from the shore, as the surf breaks more violently over these."

Recognition that

surf-riding is best attempted at coastal locations with a specific bottom

contours that provide the most suitable wave faces.

Contemporary surf-riders

must note that "a suitable wave face" is an objective function of a boards

planning chacteristics and a subjective function of their skill.

What was a perfect

wave in 6 C.E., may have not so prized two thousand years later.

10. "... a

quarter of a mile or more out to sea."

Given that the riders

are reported to ride back to the beach, this indicates rides of a significant

length.

This is approximately

440 yards or 400 metres.

11. "... watch

their (the waves) approach, and dive under water, allowing the billow to

pass over their heads."

A sophisicated method

of negotiating the (breaking) wave zone by a coordinated submerging of

board and body through the base of an approaching wave.

In contemporary

surf-riding this is known as a "duck-dive".

Although commonly

used by body-surfers, it is more difficult when attempted with a board.

For Traditional

surf-riders the low floatation of their boards (compared with the foam

boards of the Modern era) probably assisted successful completion of this

manouvre.

12. "... paddling

as it were with their hands and feet,"

Paddling in this

manner confirms board length as approximately six feet; that is,

not significantly longer than the rider's body length.

Compare the questionable

report in Thrum

(1886) that has riders paddling 18 feet Olos in this manner.

13. "... steer

with great address between the rocks,"

Although probably

achieved in a prone riding position, this certainly indicates a substanial

level of skill and possibly involves signifiacant changes of direction

("turns").

14. "... slide

off their board in a moment, grasp it by the middle, and dive under water,"

Possibly a unique

report of this technique in this period, it was reinstated to practical

use in the Classical Revival (1906 - 1950).

By the time it was

specifified as a method of dismounting Hollow

boards by John

Bloomfield in 1959 however, the Malibu board was firmly entenched

in Australia and the technique (like much of Bloomfield's book) was obsolete.

See below.

|

- News and Information Bureau. Bloomfield

(1959)

|

16. "The greatest

address is necessary in order to keep on the edge of the wave; for if they

get too far forward, they are sure to be overturned; and if they fall back,

they are buried beneath the succeeding billow."

Given that Ellis

apparently had no personal experience off surf-riding, this is a reasonable,

if slightly obtuse, attempt to decribe the complex dynamics of the take-off.

"to keep on the edge of the wave" probably means to position the board in the curl of the wave for a successful take-off.

" if they get too far forward, they are sure to be overturned" indicates that if the wave face is too steep, the rider will be unable to coordinate the take-off ("free-fall", "pearl", "nose dive" or "go over the falls", generally resulting in a "wipe-out").

"if they fall

back, they are buried beneath the succeeding billow" suggests that

a failure to take-off on a selected wave often means the succeeding wave

will break on them ("getting it on the head").

17. "when the wind blows fresh toward the shore, and spend the greater part of the day in the water." This runs counter to what are commonly considered ideal surf-riding conditions, that is with the wind blowing from the land ("off-shore").

18. "... large

corpulent men, balancing themselves on their narrow board, ... , with as

much satisfaction as youths of sixteen."

This illustrates

that body size may not directly determine the board size, particually if

the rider has substantial experience and skill.

19. "... none

of the common people are allowed to approach these places, lest they spoil

their sport."'

The tabu was probably

invoked to avoid the possibility of commoners coming into physical contact

with members of the royal caste.

20. "The chiefs

pride themselves much on excelling in some of the games of their country;

hence Taumuarii [Kaumuali'i], the late king of Tauai [Kaua'i], was celebrated

as the most expert swimmer in the surf, known in the islands." (19.)

Confirmation that

surf-riding activity was carried out and valued by all levels of Hawaiian

society.

21. "... first

question they are asked is, "Were there any sharks?"

This records the

presence of sharks as the principal danger to surf-riding, the writer having

dismissed the danger of drowning for the natives in the opening paragraphs.

22. "... a

hundred persons riding on an immense billow,"

While probably an

literary exaggeration (100 riders on the one wave?), one hundred riders

at one location may be realistic.

23. The Illustration

Most commonly available

early surf-riding images tend to indicate a realistic attempt to represent

the action of the wave mechanics.

This is often not

the case in general coastal landscapes or seascapes of the period.

Some may indicate

superior conditions by the presence of off-shore winds.

The artist usually attempts to portray the rapid motion of the rider and in most examples there are multiple surfers illustrating various activities - riding in a variety of positions, waiting outside and paddling out.

The artists also correctly note the function of stance - this is particually significant because as far as I can find it is not noted in any of the early written desciptions.

In most cases, but

there are notable exceptions, the artists incorrectly locate the rider

on the back of the wave, as noted by Bolton (1890).

If the image of

the rider was relocated on the wave face (an exercise in cut and paste

?), then possibly the illustration would closely conform to actuality.

circa 1890 ...

Dr. Bolton documented

and photographed surfing, as well as surfed on Niihau.

Of note is that

he noticed; how different surfing actually was from its popular description.

"As commonly described; in the writings of travelers, an erroneous impression is conveyed, at least to my mind, as to the position which the rider occupies with respect to the combing wave."

(Bolton quotes and compares Jarves, Isabella Bird and G. Cummings and points out the impossibility of ttle surf-riders position in Nordhoff's etching.)

"Some pictures,

too, represent the surf-riders on the seaward slope of the wave, in positions

which are incompatible with the results.

I photographed

the men of Niihau before they entered the water; while surf-riding,

and after they came out.

The second

view shows the position taken ... (Photographs i,exhibited)..."

Referred to by Tom Blake in Hawaiian Surfboard (1935) Page ?

Bolton, Dr. Henry

Carrington (1843-1903) : "Some Hawaiian Pastimes"

Journal of

American Folklore Volume 4, Number. 12,

January - March,

1894. Pages 21 to 25.

Originally presented

at the annual meeting 11/28/1890, along with "projections of the original

photographs."

No photographs

in the article.

All of the above

from Dela Vega

(ed, 2004) Page 12.

Works by Rev. William Ellis (1794-1872)

1. A Journal of

a Tour Around Hawaii, the Largest of the Sandwich Islands.

J.P. Haven New York

and Crocker, Boston,1825.

Dela Vega: 200

Years (2004), page 18, notes:

"page 65. Mentions

the heiau 'Pakiha'...when the King was playing in the surf...'

Does not contain

the chapters and descriptions of the Narrative", noted

below.

2. Narrative of

a Tour of Hawaii, or Owhyhee,with Remarks on the History, Traditions, Manners,

Customs and Language of the Inhabitants of the Sandwich Islands.

H. Fisher &

Son./ P. Jackson, London, 1825-1826.

Second Edition 1827.

Five editions by 1929.

Dela Vega: 200

Years (2004), page 18, notes the surfing content at "pp. 276-8."

3. Polynesian

Researches, During a Residence of Nearly Six Years in the Society and Sandwich

Islands, Volumes I to III.

Jackson, Fisher

& Son & Co., London, 1829.

Dela Vega: 200

Years (2004), page 18, notes

"vol I, pp. 223,

305. Ellis descr!bes surf riding in Tahiti and compares them to Hawaiians.

(Quotation)

Noted the Tahitian

surf God was named Huaouri.

Does not include

Hawaiian text."

The second edition

by Jackson, Fisher & Son & Co., London,1831, (Enlarged and Improved)

is available online at googlebooks.com

http://books.google.com/books?id=G-QBtVplc-UC&pg=PA1&dq=William+Ellis

4. Polynesian

Researches, During a Residence of Nearly Eight Years in the Society and

Sandwich Islands, Volumes I to IV..

Fisher, Son and

Jackson, London, 1831.

Dela Vega: 200

Years (2004), page 19, notes

"vol. IV, pp.

368-72. Hawaiian surfing text from the Narrative.

This edition

introduces, on its title page (See on pg. 8) the first published drawing

of a man standing on a surf- board, by F. Howard.

Both Narrative

and Polynesian Researches have been reprinted several times, and

many do not have the surfing content and etching."

Volume IV published

separately in 1969:

Ellis, Rev.

William: Polynesian Researches: Hawaii

A New Edition, Enlarged

and Improved

Charles E. Tuttle

and Company

Rutland, Vermont

and Tokyo Japan,1969.

Introduction by

Edourad R. L. Doty, 471 pages.

Fourth printing

1979.

Surfriding text

pages 368 - 372.

Surfriding illustration

frontpiece, fold-out map.

Ellis' acount of Surfriding at Waimanu

is reproduced in:

Finney, Ben and

Houston, James D. : Surfing

– A History of the Ancient Hawaiian Sport. (1996).

Appendix C. Pages

98 to 99.

The illustration by F. Howard is reproduced

on the frontpiece.

5. The American Mission in the Sandwich

Islands: A Vindication and an Appeal, in Relation to the Proceedings of

the Reformed Catholic Mission at Honolulu.

1866.

Hosted by the University of Michigan Digital

Library.

http://www.hti.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=moa;idno=AGA4516

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

Introduction to Polynesian Researches

Philip Steer

Victoria University April 2004

Introduction

William Ellis was a prominent member

of the London Missionary Society whose experience as a missionary in the

South Pacific and Madagascar provided the basis of several books. He was

born in London on 29 August 1794 and, after joining the London Missionary

Society in 1815, he and his wife lived as missionaries in the Pacific from

1816 until 1825 where his skills were employed as a printer. Returning

to England, he became secretary to the London Missionary Society and through

that role became interested in Madagascar. Following several abortive visits

in the 1850s, he lived in Madagascar from 1861 until 1865 before returning

to England where he died on 9 June 1872. His extensive work, Polynesian

Researches: During a Residence of Nearly Six Years in the South Sea Islands,

was first published in two volumes in 1829 and followed his Narrative of

a Tour through Hawaii, or Owhyee: With Observations on the Natural History

of the Sandwich Islands, and Remarks on the Manners, Customs, Traditions,

History and Language of their Inhabitants (1825), which had run to five

editions by 1828. The later work was republished in four volumes in 1831

under the title of Polynesian Researches: During a Residence of Nearly

Eight Years in the Society and Sandwich Islands, following revision by

Ellis and with the inclusion of Narrative of a Tour, and also ran into

many editions. It is now recognised as one of the earliest and most significant

ethnographic works about the South Pacific.

Some Comments on Polynesian Researches

Ellis’ Polynesian Researches are an attempt to detail his encyclopaedic knowledge of Polynesia, its cultures and the history of missionary endeavour amongst them. Volume One provides an account of the Georgian and Society Islands, beginning with their discovery by Europeans; continuing on to discuss their geography, geology, flora and fauna; before describing their inhabitants, cultural practices and myths. Volume Two describes the establishment of a missionary presence in Tahiti and the changes wrought by that presence, and Volume Three continues the narrative before concluding with a survey of other areas of Polynesia including the Marquesas, Australia and New Zealand. Volume Four describes the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), and Ellis’ participation in an 1823 missionary expedition around the island. Woven throughout are copious descriptions in minute detail of his observations of Polynesian culture and the theological concerns of the missionaries.

In his ‘Preface’, Ellis spells out his rationale for producing such a work. Despite his missionary calling, he regarded it as perfectly consistent with his office, and compatible with its duties, to collect, as opportunity offered, information on various subjects relative to the country and its inhabitants. (I.vi-vii) This perceived compatibility between religious and scientific discourses reflects the need of Victorian Evangelicals to be able to justify their faith in rational terms; as Christopher Herbert asserts, these missionaries were attempting to gather authenticated empirical proof of the proposition that unredeemed human nature is a horrifying mass of lust and wickedness. (159) Ellis writes,

The following work will exhibit numerous facts, which may justly be regarded as illustrating the essential characteristics of idolatry, and its influence on a people, the simplicity of whose institutions affords facilities for observing its nature and tendencies, which could not be obtained in a more advanced state of society.

(I.viii)

Polynesian Researches is intended to depict such “uncivilised” cultures as proof of original sin, both to bolster the credibility of the Christian faith and to demonstrate the need for the radically transformative missionary presence. Yet the ethnocentrism inherent in this view is subverted to some extent precisely by Ellis’ stated desire to preserve a written record of these cultures:

All their usages of antiquity having been entirely superseded by the new order of things that has followed the subversion of their former system…. [T]o furnish, as far as possible, an authentic record of these, and thus preserve them from oblivion, is one design which the Author has always kept in view.

(I.vii-viii)

The desire to preserve them from oblivion by implication acknowledges the validity of those cultures despite their unredeemed status, and as such undermines Ellis’ justification of his own presence. This unresolved paradox ensures that Polynesian Researches continues to be of interest.

The portrait that Ellis paints of the Polynesians is inescapably coloured by his view of their spiritual state, which must balance the demonstration of their unredeemed state with proof that they are not unredeemable. Thus, Ellis’ Tahitians surprise him with their intellect. The Society Islanders are:

[R]emarkably curious and inquisitive, and, compared with other Polynesian nations, may be said to possess considerable ingenuity, mechanical invention, and imitation…. the distinguishing features of their civil polity—the imposing nature, numerous observances, and diversified ramifications of their mythology—the legends of their gods—the historical songs of their bards—the beautiful, figurative, and impassioned eloquence sometimes displayed in their national assemblies—and, above all, the copiousness, variety, precision, and purity of their language, with their extensive use of numbers—warrant the conclusion, that they possess no contemptible mental capabilities.

(I.86)

Most impressive to him is their numeracy, indicative of higher reasoning powers: their extensive use of numbers is astonishing, when we consider that their computations were purely efforts of mind, unassisted by books or figures. (III.169) Nevertheless, such admiration is inevitably overshadowed by their moral failings; in Herbert’s terms, they are stereotypical figure[s] of boundless, exorbitant, uncontrollable desires. (160) Thus their conversation is something the ear could not listen to without pollution, presenting images, and conveying sentiments, whose most fleeting passage through the mind left contamination. (I.98) Worse still, they engage in human sacrifice and while we have been unwilling to believe they had ever been cannibals; the conviction of our mistake has, however, been impressed by evidence so various and multiplied, as to preclude uncertainty. (I.358-9). Symbolising all that must be fought are the Areois caste, a sort of strolling players, and privileged libertines, who spent their days in travelling from island to island, and from one district to another, exhibiting their pantomimes, and spreading a moral contagion throughout society. (I.86) In describing their exploits, Ellis struggles to reconcile the wish to protect his readers with his desire to achieve descriptive totality:

In some of their meetings, they appear to have placed their invention on the rack, to discover the worst pollutions of which it was possible for man to be guilty, and to have striven to outdo each other in the most revolting practices…. I should not have alluded to them, but for the purpose of shewing the affecting debasement, and humiliating demoralization, to which ignorance, idolatry, and the evil propensities of the human heart, when uncontrolled or unrestrained by the institutions and relations of civilized society and sacred truth, are capable of reducing mankind, even under circumstances highly favourable to the culture of virtue, purity, and happiness.

(I.244-5)

The fact that such “revolting practices” can occur within a climate that might be thought to encourage “virtue, purity, and happiness” allows Ellis to reject any notion of the noble savage:

I should not have dwelt so long on the distressing facts that have been given, but to exhibit in the true, though by no means strongest colours, the savage character and brutal conduct of those, who have been represented as enjoying, in their rude and simple state, a high degree of happiness, and cultivating all that is amiable and benevolent.

(I.312)

In this way, the emergent scientific discourse of ethnographic observation is yoked not only to Evangelical theology but also to wider racial debates.

As well as detailing the usages of antiquity, Ellis also narrates a history of cultural contact. His description of the early missionary presence is notable for the recurrent subversion of their expectations. Not only were the missionaries completely dependent upon their Tahitian hosts, but those hosts failed to concede any form of independence or spiritual authority to them:

All that the settlers ever desired was, the permanent occupation of the ground on which their dwellings and gardens were situated; yet, in writing to the Society, in 1804, they remark, in reference to the district, “The inhabitants do not consider the district, nor any part of it, as belonging to us, except the small sandy spot we occupy with our dwellings and gardens; and even as to that, there are persons who claim the ground as theirs.” Whatever advantages the king or chiefs might expect to derive from this settlement on the island, they were not influenced by any desire to receive general or religious instruction.

(II.9-10)

Those gardens became a further symbol of the disruption of their expectations, as the missionaries sought to establish the plants that were to be at the forefront of their civilising efforts. Wheat grew well but produced no grain, while potatoes deteriorated when replanted the next season and Ellis mournfully reports that the coffee and the cashew-nuts were totally destroyed by the goats, which, leaping the fence one day, in a few minutes ate up the plants on which I had bestowed much care. (I.67) The endeavour of learning the local language was another arena that sorely tested their notions of cultural superiority:

[The Missionaries] had no elementary books to consult, no preceptors to whom they could apply, but were frequently obliged, by gestures, signs, and other contrivances, to seek the desired information from the natives; who often misunderstood the purport of their questions, and whose answers must, as often, have been unintelligible to the Missionaries.

(II.115-6)

Nevertheless, Polynesian Researches is testament to the enormous social changes that the missionaries began to achieve once they became established. These began with the destruction of indigenous spirituality, whose physical structures provided the clearest evidence of their former idolatry:

A short time before sun-set, Patii appeared, and ordered his attendants to apply fire to the pile. This being done, he hastened to the sacred depository of his gods, brought them out, not indeed as he had been on some occasions accustomed to do, that they might receive the blind homage of the waiting populace,—but to convince the deluded multitude of the impotency and the vanity of the objects of their adoration and their dread…. Patii tore off the sacred cloth in which they were enveloped, to be safe from the gaze of vulgar eyes; stripped them of their ornaments, which he cast into the fire; and then one by one threw the idols themselves into the crackling flames…. Thus were the idols which Patii, who was a powerful priest in Eimeo, had worshipped, publicly destroyed.

(II.112-3)

Such actions bring the missionaries great joy, but prove to have consequences beyond their expectation. As Ellis describes, The intimate connexion between the government and their idolatry, occasioned the dissolution of the one, with the abolition of the other; and when the system of pagan worship was subverted, many of their ancient usages perished in its ruins. (III.133) This reveals a fundamental difference over the nature of religion between the missionaries and their converts, for to the former it appeared most important to impress the minds of the people with the distinctness of a Christian church from any political, civil, or other merely human institution. (III.57) This is brought to a head when the missionaries are asked to help in the production of a code of laws, a document that essentially amounted to a constitution. Despite apparently resisting the idea, they are ultimately unable to escape it:

During many years of our residence in these islands, we most carefully avoided meddling with their civil and political affairs, except in a few instances, where we endeavoured to promote peace between contending parties. At present, however, it appears almost impossible for us, in every respect, to follow the same line of conduct…. The first code of laws was that enacted in Tahiti in the year 1819; it was prepared by the king and a few of the chiefs, with the advice and direction of the Missionaries, especially Mr. Nott, whose prudence and caution cannot be too highly spoken of, and by whom it was chiefly framed.

(III.137-8)

Such incidents suggest a fluctuation of authority — religious and social — between the two cultures that complicates what at first appearance seems a simple picture of colonialism. As with the image of the first communion, where a lack of wheat means that the bread is substituted with baked breadfruit, the missionaries at times appear threatened with the possibility that they might be changed as much by the encounter as the Polynesians.

Nevertheless, Polynesian Researches also reveals the many-faceted and wide-reaching nature of the conversion sought by the missionaries through the depiction of the means by which this was achieved. Pre-eminent for Ellis are the introduction of written language, and its dissemination through printing:

The use of the press in the different islands, we naturally regard as one of the most powerful human agencies that can be employed in forming the mental and moral character of the inhabitants, imparting to their pursuits a salutary direction, and promoting knowledge, virtue, and happiness. It is not easy to estimate correctly the advantages already derived from this important engine of improvement.

(II.237)

Their use of writing to influence “the mental and moral character of the inhabitants” places the missionaries at the forefront of the colonial endeavour. When the halting means by which they first learnt to communicate with the Tahitians are recalled, it becomes apparent that controlling such an “engine of improvement” enabled a radical change of the missionaries’ status and ability to achieve cultural hegemony. This is illustrated by the changing status of indigenous women, whose newfound literacy is paralleled by a desire to adopt other practices that the missionaries deem appropriate for women:

The females, no longer exposed to that humiliating neglect to which idolatry had subjected them, enjoyed the comforts of domestic life, the pleasure resulting from the culture of their minds, the ability to read the scriptures, and to write in their own language, in which several excelled the other sex; they also became anxious to engage in employments which are appropriated to their own sex in civilized and Christian communities. They were therefore taught to work at their needle, and soon made a pleasing proficiency.

(II.389)

Not only does Ellis associate the propagation of Christianity with the adoption of British culture, but he also demonstrates it to be inseparable from capitalism. He relates that one of the most formidable barriers to their receiving our instructions, imbibing the spirit and exhibiting the moral influence of religion, and advancing in civilization has been a lack of indigenous desire for self-improvement:

The difficulties we encountered resulted not less from the inveteracy of their idle habits, than from the absence of all inducements to labour, that were sufficiently powerful to call into action their dormant energies. Their wants were few, and their desires limited to the means of mere animal existence and enjoyment; these were supplied without much anxiety or effort, and, possessing these, they were satisfied.

(II.279)

The attempts of the earliest missionaries to rouse them from their abject and wretched modes of life, by advising them to build more comfortable dwellings, to wear more decent clothing, and to adopt, so far as circumstances would admit, the conveniences and comforts of Europeans were frustrated by the sheer apathy and lack of concern of their heathen audience. Ellis comments of this, They furnish a striking illustration of the sentiment, that to civilize a people they must first be christianized; that to attempt the former without the latter, is like rearing a superstructure without a foundation. As a consequence, the Tahitian converts are inculcated with a Protestant work ethic to the effect that idleness, and irregular and debasing habits of life, were as opposed to the principles of Christianity, as to their own personal comfort. Furthermore, to ensure its long-term viability they establish consumerism upon the island:

To increase their wants, or to make some of the comforts and decencies of society as desirable as the bare necessaries of life, appeared to us the most probable method of furnishing incitements to permanent industry.

(II.280)

Such confessions illustrate one of the

greatest ironies of Polynesian Researches. While purporting to be an ethnographic

text about the cultures of Polynesia, it demonstrates to an equal degree

the values and assumptions of British culture and one of its means of self-propagation

through the extension of Empire.

Bibliography

Blaikie, W.G. “Ellis, William (1794–1872)”. In Dictionary of National Biography: Volume VI, Drant-Finan. Ed. Leslie Stephen and Sydney Lee. London: Smith, Elder & Co, 1908, pp. 714–715.

Edmond, Rod. “Translating Cultures: William Ellis and Missionary Writing”. In Science and Exploration: European Voyages in the Southern Oceans in the Eighteenth Century. Ed. Margarette Lincoln. Suffolk: Boydell Press, 1998, pp. 149–161.

Herbert, Christopher. Culture and Anomie: Ethnographic Imagination in the Nineteenth Century. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Ellis is a somewhat neglected figure,

but Herbert’s discussion of Polynesian Researches within the wider context

of contemporary Polynesian ethnography is an excellent introduction to

his work and concerns.

Selected Links

J. Paul Getty Museum

Provides a brief biography of Ellis, focusing on his later interest in photography and its relationship to his missionary work, with a link to his photograph, “Madagascar Portrait” (1862). Hosted by the J. Paul Getty Trust.

http://www.getty.edu/art/collections/bio/a2909-1.html

Making of America Books

Online version of Ellis’ The American Mission in the Sandwich Islands: A Vindication and an Appeal, in Relation to the Proceedings of the Reformed Catholic Mission at Honolulu (1866). Hosted by the University of Michigan Digital Library.

http://www.hti.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=moa;idno=AGA4516

Home | Advanced Search | About

© 2007 Victoria University of Wellington

http://books.google.com/books?id=npADAAAAQAAJ&printsec=titlepage&dq=Faahee#PPR4,M1

http://books.google.com/books?id=G-QBtVplc-UC&pg=PA1&dq=William+Ellis

WIKIPEDIA

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Ellis_(author)

William Ellis (1794-1872) was an English missionary and author.

Born in London of working class parents in straightened circumstances, he developed a love of plants in his youth and became a gardener, first in the East of England, then at a nursery north of London and eventually for a wealthy family in Stoke Newington. Being of a religious nature, he applied to train as Christian missionary for the London Missionary Society and was accepted. Ordained in 1815, he was posted to the South Sea Islands with his wife, leaving England in 1816. They arrived at Eimeo, one of the Windward Islands, via Sydney and learnt the language there. During their stay there several chiefs of nearby Pacific islands who had assisted Pomare in regaining sovereignty of Tahiti, visited Eimeo and welcomed the LMS missionaries (including John Orsmond and John Williams and their wives) to their own islands. All three missionary families went to Huahine , arriving in June 1818, drawing crowds from neighbouring islands, including King Tamatoa of Raiatea. In 1822, William Ellis went on elsewhere in the Sandwich Islands but in 1825 had to return to England, Mrs Ellis being in poor health, so took a ship via Hawaii and America. Back in London, Rev. William Ellis became Assistant Foreign Secretary of the London Missionary Society (1830), and then Chief Foreign Secretary. Mrs Elllis died in 1835.

'Life of William Ellis' by John Eimeo Ellis and Henry Allon, 1873

Page 152

... managing of the vessels one

of the most general and important of their vocations.

It also procures no small respect

and endowment lor the 'Tahua tarai vaa', builder of canoes.

'Vaa waa', or 'vakaa', is the name

of a canoe, in most of the islands of the Pacific; though by foreigners

they are uniformly called canoes, a name first given to this sort of boat

by the natives of the Caribean Islands*, and adopted by Europeans ever

since, to designate the rude boats used by the uncivilized natives in every

part of the world.

The canoes of the Society Islanders

are various, both in size and shape, and are double or single. Those belonging

to the principal chiefs, and the public district canoes, were fifty, sixty,

or nearly seventy feet long, and each about two feet wide, and three or

four feet deep; the sterns remarkably high, sometimes fifteen or eighteen

feet above the water, and frequently ornamented with rudely carved hollow

cylinders, square pieces, or grotesque figures, called 'tiis'.

The rank or dignity of a chief was

supposed, in some degree, to be indicated by the size of his canoe, the

carving and ornaments with which it was embellished, and the number of

its rowers.

Next in size to these was the 'pahi',

or war canoe.

I never saw but one of these: the

stern was low, and covered, so as to afford a shelter from the stones and

darts of the assailants; the bottom was round, the upper part of the sides

narrower, ...

Footnote

*After his first interview with

the natives of the newly discovered islands, in the Caribbean sea we are

informed by Robertson, that Columbus retumed to his ship, accompanied by

many of the islanders in their boats, which they called 'canoes',

and though rudely formed out of the trunk of a single tree, they rowed

them with surprising dexterity.

Page 153

and perpendicular; a rude imitation

of the human head, or some other grotesque figure, was carved on the stern

of each canoe.

The stem, often elevated and curved

like the neck of a swan, terminated in the carved figure of a bird's head,

and the whole was more solid and compact than the other vessels.

In some of their canoes, and in

the pahi among the rest, a rode sort of grating, made with the light but

tough wood of the bread-fruit tree, covered the hull of the vessels, the

intervening space between them, and projected a foot or eigh- ...

Image

... teen inches over the outer edges.

On this the rowers usually sat;

and here the mariners, who attended to the sails, took their stations,

and found it much more convenient and secure than standing on the narrow

edges of the canoes, or the curved and circular beams that held them together.

There was a!so a kind of platform

in the front, or generally near the centre, on which the fighting men were

stationed: these canoes were sometimes sixty feet long, between three and

four ...

Page 154

feet deep, and, with their platforms

in front or in the centre, were capable of holding fifty fighting men.*

The vaatii, or sacred canoe, was

always strong and large, more highly ornamented with carving and feathers

than any of the others.

Small houses were erected in each,

and the image of the god, eometimea in the shape of a large bird, at other

times resembling a hollow cylinder, ornamented with various coloured feathers,

was kept in these houses.

Here their prayers were preferred,

and their sacrifices offered.

Their war canoes were strong, well-built,

and highly ornamented.

They formerly possessed large and

magnificent fleets of these, and other large canoes; and, at their general

public meetings, or festivals, no small portion or the entertainment was

derived from the regattas, or naval reviews, in which the whole fleet,

ornamented with carved images, and decorated with flags and streamers,

or various native-coloured cloth, went through their different tactics

with great precision.

On these occasions the crews which

they: were navigated, anxious to gain the plaudits of the king and chiefs,

emulated each other in the exhibition of their seamanship.

The vaati, or sacred canoes, formed

part of every fleet, and were generally the most Imposing in appearance,

and attractive in their decorations.

The peculiar, and almost classical shape or the large Tahitian canoes, the elevated prow and stern, the rude figures, carving, and other omaments, the loose-flowing drapery of the natives on board, and the maritime aspect of their general places of abode, are all adapted to produce a singular effect ...

Footnote

*In Cook's voyages a description

is given of some, one hundred and eight feet long.

Page 155

... on the mind of the beholder.

I have often thought, when I have

seen a fleet of thirty or forty approaching the shore, that they exhibited

no faint representation of the ships in which the Argonauts sailed, or

the vessels that conveyed the heroes of Homer to the Trojan shores.

Every large canoe had a distinct

name, always arbitrary, but frequently descriptive of some real or imaginary

excellence In the canoe, or in memory of some event connected with it.

Neither the names of any of their

gods, or chiefs, were ever given to their vessels; such an act, instead

of being considered an honour, would have been deemed the greatest insult

that could have been offered.

The names of canoes, in some instances,

appear to have been perpetuated, as the king's state canoe was always called

Anuanua, or the rainbow.

The most general and useful kind

of canoe it the tipairua, or common double canoe, usually from twenty to

thirty feet long, strong and capacious, with a projection from the stem,

and a low shield-shaped stern.

These are very valuable, and usually

form the mode of conveyance for every chief of respectability or inftuence,

in the island.

They are also used to transport

provisions, or ot1ler goods, from one place to another.

One of these, in which we voyaged

to Afareaitu soon after our arrival, was between thirty and forty feet

in length, strong, and, as a piece of native workmanship, well built.

The keel was formed with a number

of pieces of tough tamanu wood, 'inophyllum caliophyllum, twelve or sixteen

inches broad, and two inches thick, hollowed on the inside, and rounded

without, so as to form a convex angle along the bottom of the canoe; these

were fastened together by lacings of tough elastic ...

Page 156

... cord, made with the fibres of

the cocoa-nut husk.

On the front end of the keel, a

solid piece, cut out of the trunk of a tree, so contrived as to constitute

the forepart of the canoe; was fixed with the same lashing; and on the

upper part of it, a thick board or plank projected horizontally, in a line

parallel with the surface of the water.

This front piece, usually five or

six feet long, and twelve or eighteen inches wide, was called the 'ihu

vaa', nose of the canoe, and without any joining, comprised the stem, bows,

and bowsprit of the vessel.

The sides of the canoe were composed

of two lines of short plank, an inch and a half or two inches thick.

The lowest line was convex on the

outside, and nine or twelve inches broad; the upper one straight. The stern

was considerably elevated, the keel was inclined upwards, and the lower

part of the stern was pointed, while the upper part was flat, and nine

or ten feet above the level of the sides.

The whole was fastened together

with cinet, not continued along the seams, but by two, or, at most, three

holes made in each ,board, withtin an, inch of each other, and corresponding

holes made in the opposite piece, and the lacing passed through from one

to the other.

A space of nine inches or a foot

was left, and then a similar set of holes made.

The joints or seams were not grooved

together, but the edge of one simply laid on that of the other, and fitted

with remarkable exactness by the adze of the workman, guiided only by his

eye: they never used line or rule.

The edges of their planks were usually

covered with a kind of pitch or gum from the bread-fruit tree, and a thin

layer of cocoa-nut husk spread between them.

The husk of the cocoa-nut swelling

when in contact with water, ...

Page 157

fills any apertures that may exist,

and, considering the manner in which they are put together, the canoes

are often remarkably dry.

The two canoes were fastened together

by, strong curved pieces of wood, placed horizontally across the upper

edges of the canoes, to which they were fixed by strong lashings of thick

coiar cordage.

Illustration: Skreened Canoe.

The space between the two bowsprits,

or broad planks projecting from the front of our canoe, was covered with

boards, and furnished a platform of considerable extent; over this a kind

of temporary awning of platted cocoa-nut leaves was spread, and under it

the passengers sat during the voyage. The upper part of each of the canoes

was not above twelve or fifteen inches wide; little projections were formed

on the inner part of the sides, on which small moveable thwarts or seats

were fixed, whereon the men sat who wrought with the paddle; while the

luggage was placed in the bottom, piled up against the stern, or laid on

the elevated stage between the two canoes.

The heat of the sun was extreme,

and the awning afforded a grateful shade.

Page 158

The rowers appeared to labour hard.

Their paddles, being made of the

tough wood of the hibiscus, were not heavy; yet, having no pins in the

sides of the canoe, against which the handles of the paddles could bear,

but leaning the whole body over the canoe, first on one side, and then

on the other, and working the paddle with one hand near the blade, and

the other at the upper end of the handle, and shovelling as it were the

water, appeared a great waste of strength.

They often, however, paddle for

a time with remarkable swiftness, keeping time with the greatest regularity.

The steersman stands or sits in

the stern, with a large paddle; the rowers sit in each canoe two or three

feet apart; the leader sits next; the steersman gives the signal to start,

by striking his paddle violently against the side of the canoe; every paddle

is then put in and taken out of the water with every stroke at the same

moment; and after they have thus continued on one side for five or six

minutes, the leader strikes his paddle, and the rowers instantly and simultaneously

turn to the other side, and thus alternately working on each side of the

canoe, they advance at a considerable rate. There is generally a good deal

of striking the paddle when a chief leaves or approaches the shore, and

the effect resembles that of the smacking of the whip, or sounding of the

horn, at the starting or arrival of a coach.

They have also a remarkably neat

double canoe, called Maihi, or twins, each of which is made out of a single

tree, and are both exactly alike.

The stem and stern are usually sharp;

although, occasionally, there is a small board projecting from each stem.

These are light, safe, and swift,

easily managed, and seldom used but by the chiefs.

The ...

Page 159

... late king Pomare was fond of

this kind of conveyance.

The single canoes are built in the

same manner, and with the same materials, as the double ones. Their usual

name is 'tipaihoe', and they are more various in their kind than the others.

The small 'buhoe', the literal name

of which is single shell, is generally a trunk of a tree, seldom more than

twenty feet in length, rounded on the outside, and hollow within; sometimes

sharp at both ends, though generally only at the stern.

It is used by fishermen among the

reefs, and also along the shore, and in shallow water, seldom carrying

more than two persons.

The single maihi is only a neater

kind of buhoe.

Chapter VII

Page 160

The 'vaa motu', island-canoe, is

generally a large, strong, single vessel, built for sailing, and principally

used in distant voyages.

In addition to the ordinary edge,

or gunwale, of the canoe, flanks, twelve or fifteen inches wide, are fastened

along their sides, after the manner of wash-boards in a European boat.

The same are also added to double

canoes, when employed on long voyages.

A single vaa is never used without

an outrigger, varying in size with the vessel; it is usually formed with

a light spar of the hibiscus, or of the erythrina, which was highly prized

as an 'ama', or outrigger, on account of its being both light and strong.

This is always placed on the left

side, and fastened to the canoe by two horizontal poles, from five to eight

feet long; the front one is straight and firm, the other curved and elastic;

it is so fixed, that the canoe, when empty, does not float upright, being

rather inclined to the left; but, when sunk into the water, on being laden,

it is generally erect, while the outrigger, which ...

Page 161

... is firmly and ingeniously fastened

to the sides by repeated bands of cinet, floats on the surface.

In addition to this, the island

canoes have a strong plank, twelve or fourteen feet Iong, fastened horizontally

across the centre, in an inclined position, one end attached to the outrigger,

and the other extending five or six feet over the opposite side, and perhaps

elevated four or five feet above the sea.

A small railing of rods is fastened

along the sides of this plank, and it is designed to assist the navigators

in balancing the keel, as a native takes his station on the one side or

the other, to counteract the inclination which the wind or sea might give

to the vessel.

Sometimes they approach the shore

with a native standing or sitting on the extremity of the plank, and presenting

a singular appearance, which it is impossible to behold without expecting

every undulation of the sea will detach him from his apparently insecure

situation, and precipitate him into the water.

Illustration: Single, or Island Canoe.

This kind of canoe (see next page) is principally employed in the voyages which the natives make to 'Tetuaroa', a cluster of islands, five in number, to the north of Tahiti.

In navigating their double canoes,

the natives frequently use two sails, but in their single vessels only

one.

The masts are moveable, and are

only raised when the sails are used.

They are slightly fixed upon a step

placed across the canoe, and fastened by strong ropes or braces extending

to both sides, and to the stem and stern.

The sails were made with the leaves

of the pandanus split into thin strips, neatly woven into a kind of mat-

...

Page 162

... ting.

The shape of the sails of the island-canoes

is singular, the side attached to the mast is straight, the outer part

resembling the seetion of an oval, but in the longest direction.

The other sails are commonly used

in the same manner as sprit or lugger sails are used in European boats.

The ropes from the comers of the

sails are not usually fastened, but held in the hands of the natives. The

rigging is neither varied nor complex ; the cordage is made with the twisted

bark of the hibiscus, or the fibres of the cocoa- nut husk- of which a

very good 'coiar' rope is manufactured.

The paddles of the Tahitians are

plain, having a smooth round handle, and an oblong-shaped blade. Their

canoes having no rudder, are steered by a man in the stern, with a paddle

generally longer than the rest.

In long voyages, ...

Page 163

... they have

two or three steering paddles, including a very large one, which they employ

in stormy weather, to prevent the vessel from drifting to leeward.

Temariotuu,

the god of mariners and pilots, was stated to have made his rudder, or

steering-paddle, from the sacred aito of Ruaioroirai.

The 'tataa',

or scoop, with which they bale out the leakage, is generally a neat and

convenient article, cut out of a solid piece of wood.

Their canoes

were formerly ornamented with streamers of various coloured cloths; and

tufts of fringe and tassels of feathers were attached to the masts and

sails, though they are now seldom used.

A small kind

of house or awning was erected in the centre, or attached to the stern,

to skreen the passengers from the sun by day and the damp by night.

The latter

is still used, though the former is but seldom seen.

They do not

appear ever to have ornamented the body or hull of their vessels with carving

or painting; but, notwithstanding this seeming deficiency, they had by

no means an unfinished appearance.

In building

their vessels, all the parts were first accurately fitted to each other,

the whole was taken to pieces, and the outside of each plank smoothed by

rubbing it with a piece of coral and sand moistened with water; it was

then dried, and polished with fine dry coral.

The wood was

generally of a rich yellow colour, the cinet nearly the same, and a new

well-built canoe is perhaps one or the best specimens of native skill,

ingenuity, and perseverance, to be seen in the islands.

Most of the

natives can hollow out a buhoe, but it is only those who have been regularly

trained to the work, that can build a large canoe, and in this there is

a considerable division of labour ,- some ...

Page 164

... laying down the keel and building

the hull, some making and fixing the sails, and others fastening the outriggers,

or adding the ornaments.

The principal chiefs usually kept

canoe-builders attached to their establishments, but the inferior chiefs

generally hire workmen, paying them a given number of pigs, or fathoms

of cloth, for a canoe, and finding them in provision while they are employed.

The trees that are cut down in the

mountains, or the interior of the islands, are often hollowed out there,

sometimes by burning, but generally by the adze, or cut into the shape

designed, and then brought down to the shore.

Idolatry was interwoven with their

naval architecture, as well as every other pursuit.

The priest had certain ceremonies

to perform, and numerous and costly offerings were made to the gods of

the chief, and of the craft or profession, when the keel was laid, when

the canoe was finished, and when it was launched.

Valuable canoes were often among

the national offerings presented to the gods, and afterwards sacred to

the service of the idol.

The double canoes of the Society

Islands were larger, and more imposing in appearance, than most of those

used in New Zealand or the Sandwich Islands, but not so strong as the former,

nor so neat and light as the latter.

I have, however, made several voyages

in them.

In fine weather, and with a fair

wind, they are tolerably safe and comfortable; but when the weather is

rough, and the wind contrary, they are miserable sea-boats, and are tossed

about completely at the mercy of the winds.

Many of the natives that have set

out on voyages from one island to another, have been carried from the ...

Page 165

... group altogether, and have either

perished at sea, or drifted to some distant island.

In long voyages, single canoes are

considered safer than double ones, as the latter are sometimes broken asunder,

and are then unmanageable; but, even tltough the former should fill or

upset at sea; as the wood is specifically lighter than the water; there

is no fear of their sinking.

When a canoe is upset or fills,

the natives on board jump into the sea, and all taking hold of one end,

which they press down, so as to elevate the other end above the sea, a

great part of the water runs out; they then suddenly loose their hold of

the canoe, which falls upon the water, emptied in some degree of its contents.

Swimming along by the side of it,

they bale out the rest, and climbing into it pursue their voyage.

This has frequently been the case;

and, unless the canoe is broken by upsetting or filling, the detention

is all the inconvenience it occasions.

The only evil they fear in such

circumstance, is that of being attacked by sharks, which have sometimes

made sad havock among those who have been wrecked at sea.

An instance of this kind occurred

a few years ago, when a number of chiefs and people, altogether thirty-two,

were passing from one island to another, in a large double canoe.

They were overtaken by a tempest,

the violence of which tore their canoes from the horizontal spars by which

they were united.

It was in vain for them to endeavour

to place them upright, or empty out the water, for they could not prevent

their incessant overturning.

As their only resource, they collected

the scattered spars and boards, and constructed a raft, on which they hoped

they might drift to land.

The weight of the whole number,

...

Page 166

... who were now ,collected on the

raft; was so great as to sink it so far below the surface, that they sometimes