|

surfresearch.com.au

cook : polynesian surf-riding, circa 1779 |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

Excerpt

2 : George Gilbert, midshipman 'Resolution'.

Surfboard

Paddling

Kealakekua Bay,

Hawaii.

February, 1779.

Excerpt

3 : David Samwell, Surgeon's Mate, 'Resolution'.

Surf-riding

Kealakekua Bay,

Hawaii.

22nd January,

1779.

Excerpt

4 : James King's Unedited log

Surf-riding

Kealakekua Bay,

Hawaii.

March 1779.

Excerpt

5 : James King's Edited Log

Surf-riding

Kealakekua Bay,

Hawaii, March 1779.

Reproduced in:

Zug, James: The Last Voyage Of Captain

Cook: The Collected Writings of John Ledyard

National Geographic Society, Washington,

D.C., U.S.A., 2005.

On the 17th January, 1779, we entered

our harbour, which was a comodious bay situate nearly in the middle of

the south side of Owyhee, and about a mile and a half deep, the extremes

of the bay distant about two miles.

We entered with both ships, and anchored

in 7 fathoms water about the middle of the bay having on one side a town

containing about 300 houses called by the inhabitants Kiverua, and on the

other side a town containing 1100 houses, and called Kirekakooa.

While we were entering the bay which

they called Kirekakooa after the town Kirekakooa we were surrounded by

so great a number of canoes that Cook ordered two officers into each top

to number them with as much exactness as they could, and as they both exceeded

3000 in their amounts I shall with safety say there was 2500 and as there

were upon an avarage 6 persons at least in each canoe it will follow that

there was at least 15000 men, women and children in the canoes, besides

those that were on floats, swimming without floats, and actually on board

and hanging round the outside of the ships.

The crouds on shore were still more

numerous.

The beach, the surrounding rocks, the

tops of houses, the branches of trees and the adjacent hills were all covered,

and the shouts of joy, and admiration proceeding from the sonorous voices

of the men confused with the shriller exclamations of the women dancing

and clapping their hands, the overseting of canoes, cries of the children,

goods on float, and hogs that were brought to market squalling formed one

of the most tumultuous and the most curious prospects that can be imagined.

NOTES

While James Zug notes in his introduction

(page XXI and following) that Ledyard substantially plagerized several

of the available published accounts of Cook's voyages, this is the only

written report of surfboards ("floats") in use as water transport

on the expedition's initial entry into Kealakekua

Bay, Hawaii, on 17th January 1779.

As such it confirms the illustration by

John Webber,

see below.

Ledyard's estimation of the number of

canoes and their occupants is significantly larger than reported by King:

"about the Resolution 500 Canoes and about the Discovery

475", see below.

Possibly from

Christine Holmes

(editor). Captain Cook's Final Voyage: The Journal of Midshipman George

Gilbert.

: Caliban Books,

Horsham, Sussex. University of Hawaii Press. 1982. Page?

They lay themselves upon it length ways, with their breast about the centre; and it being sufficient to buoy them up they paddle along with their hands and feet at a moderate rate, having the broad end foremost (5); and that it may not meet with any resistance from the water, they keep it just above the surface by weighing down upon the other, which they have underneath them, betweeen their legs. (6)

These pieces of wood are so nicely balanced that the most expert of our people at swimming could not keep upon them half a minuit without rolling off." (7)

NOTES

1.

"have a method of swimming upon a piece of wood"

This reference only

records the use of a surfboard as a mode of transport, as illustrated in

Webber's

illustration

and does not indicate surf-riding activity.

This overwise simple

observation, may however establish a relationship between board paddling

and the development of Polynesian swimming technique - the overarm

stroke with flutter kick.

2. "form of

a blade of an oar"

Indicates the board

was flat and probably possiblyly with a rounded, not a square, nose.

3. "about six

feet in length, 16 inches in breadth at one end and about nine at the other,

tapering

down

These dimensions

are close to Samwell's "a thin board about

six or seven foot long & about 2 (foot) broad "

Dimensions are not

included in either of the published entries attributed to James

King.

Significantly, this

report notes the characteristics of the template, probably 16'' wide near

the nose and a 9'' tail.

4. "four or

five inches thick, in the middle tapering down to an inch at the sides.""

The thickness and

rail taper are also not included in the other reports from the voyage.

The thickness seems

extreme compared with later accounts and to existing examples from the

period.

5. "having

the broad end foremost"

The widest part

of the board is the nose.

6. "They lay

themselves ... betweeen their legs."

A detailed account

of the mechanics of board paddling.

7. "... the

most expert of our people ..."

Patrick Moser noted,

July 2006 (see Correspondence) "This last observation

at leasts suggests that some of Cook's men may have tried paddling (or

surfing?) on these boards themselves."

I would contend

that the report specifically records attempts by members of the crew

to paddle the boards, without success.

The skill of board

paddling is fundamental to successful surf-riding and it is often overlooked

by modern commentators.

The report is also

consistant with Ellis' comment (see Point 5) that

implies the boards have been examined closely and must have been held to

report the weight.

Furthermore, the

sentence also conforms with the relective nature of the account, that probably

indicates it is based on multiple observations.

GEORGE GILBERT

"George Gilbert’s

writing has been lauded as even-handed, even mature, reminiscent of the

“magnificent lack of imagination” displayed by the younger James Cook in

his Endeavour journal.

George Gilbert

joined Captain Cook’s 1776 expedition as a seaman and was promoted to midshipman

during the voyage.

His father

George Gilbert had served as master on the the 'Resolution' for its preceding

voyage to the Pacific, during which time Cook had named Gilbert Island

off the coast of Tierra del Fuego for him. Upon his father’s retirement,

John Gilbert had been replaced as master by William Bligh, later deposed

as captain during the mutiny on the Bounty.

While in his

late teens or early twenties, Gilbert was on the 'Resolution' when Cook

visited Nootka Sound and undertook repairs from late March 1778 until April

27.

His extensive

account of their travels was not included within The Journals of Captain

Cook. Vol. 3. Parts 1 & 2, Resolution and Discovery—as were extracts

from journals by his contemporaries Anderson, Clerke, Burney, Williamson,

Edgar and King—because Gilbert’s 325-page manuscript journal was likely

completed in the early 1780s.

Gilbert’s memoir

was not published until two centuries later, 80 years after a descendant

of Gilbert’s brother, Richard Gilbert, took the manuscript to the British

Museum in 1912.

...

After Cook’s

death, Gilbert transferred to the 'Discovery' under Captain Clerke and

was paid off at Woolwich on October 21, 1780.

He became

fifth lieutenant on the warship 'Magnificent' until 1783.

The year and

nature of his death are not known.

Gilbert’s

original journal is in the British Museum."

2. Following

the posting of Samwell's account to Joe Tabler

at surfbooks.com, I was contacted in July 2006 by Patrick Moser,

Drury University, who provided the complete Gilbert quotation, as posted

above.

Patrick Moser also

provided the date, a probable location and noted ...

This last observation

at leasts suggests that some of Cook's men may have tried paddling (or

surfing?) on these boards themselves.

See Point 7. above,

full email attached below.

Thanks to Patrick

Moser for his substantial contribution to this subject.

"As two or three of us were walking along shore to day we saw a number of boys & young Girls (1) playing in the Surf, which broke very high on the Beach as there was a great swell rolling into the Bay. (2)

In the first place they provide themselves with a thin board about six or seven foot long & about 2 broad (3) , on these they swim off shore to meet the Surf (4) , as soon as they see one coming they get themselves in readiness & turn their sides to it (5) , they suffer themselves to be involved in it (6) & then manage so as to get just before it or rather on the Slant or declivity of the Surf (7), & thus they lie with their Hands lower than their Heels laying hold of the fore part of the board which receives the force of the water on its under side (8) , & by that means keeps before the wave which drives it along with an incredible Swiftness to the shore. (9)

The Motion is so rapid for near the Space of a stones throw that they seem to fly on the water, the flight of a bird being hardly quicker than theirs.

On their putting off shore if they ...

Page 1165

... meet with

the Surf too near in to afford them a tolerable long Space to run before

it they dive under it with the greatest Ease (10)

& proceed

further out to sea. (11)

Sometimes they fail in trying to get before the surf, as it requires great dexterity & address, and after struggling awhile in such a tremendous wave that we should have judged it impossible for any human being to live in it, they rise on the other side laughing and shaking their Locks & push on to meet the next Surf when they generally succeed, hardly ever being foiled in more than one attempt. (12)

Thus these People find one of their Chief amusements (13) in that which to us presented nothing but Horror & Destruction, and we saw with astonishment young boys & Girls about 9 or ten years of age (14) playing amid such tempestuous Waves that the hardiest of our seamen would have trembled to face, as to be involved in them among the Rocks, on which they broke with a tremendous Noise, they could look upon as no other than certain death. (15)

So true it is that many seeming difficulties are easily overcome by dexterity & Perseverance. (16)"

NOTES

1. "a number

of boys & young Girls"

Samwell notes that

surf-riding is a community activity including both sexes and juvenile riders.

He later makes his

remarks more specific, see 13.

2. "a great

swell rolling into the Bay."

Suitable swell conditions

are not consistently available and in this case breaking close to the shore.

3. "a thin

board about six or seven foot long & about 2 (foot) broad "

This dimensions

appear practical and are close to Gilbert's "about six feet

in length, 16 inches in breadth" - see Extract 1.

4. "swim off

shore to meet the Surf "

Paddling out through

the surf line.

5. "in readiness

& turn their sides to it"

The rider's preparation

and positioning for the take-off.

6. "to be involved

in it"

Possibly indicates

a take-off in the white-water or the broken water of a wave.

Technically a wave

of translation.

7. "get just

before it or rather on the Slant or declivity of the Surf"

This appears to

indicate the riders attempt to ride on the sloping wave face, in preference

to the white-water.

declivity : a downward

slope, Macquarie Dictionary (1991).

8. "lie

with their Hands lower than their Heels laying hold of the fore part of

the board which receives the force of the water on its under side"

Classic prone surf-riding

technique.

Possibly indicates

that the rider's feet were raised out of the water.

9. "an incredible

Swiftness to the shore."

The speed of the

riders is often reported by early observers, this may indicate that "swiftness"

was a factor of angling across the wave face and travelling faster than

the wave speed.

Banks (1769) uses

exactly the same expression.

See Banks

: Tahiti 1769 Note 12.

10. "too near

in to afford them a tolerable long Space to run before it they dive under

it with the greatest Ease"

In contemporary

surf-riding terminology, this manoeuvre is known as a 'duck-dive" and was

first illustrated by

Wallis McKay, circa

1874.

Also reported by

Banks,

Note 14.

11. "&

proceed further out to sea."

A continuous process

of wave riding followed by paddling back out through the surf.

12. "Sometimes

they fail in trying to get before the surf, as it requires great dexterity

& address, and after struggling awhile in such a tremendous wave that

we should have judged it impossible for any human being to live in it,

they rise on the other side laughing and shaking their Locks & push

on to meet the next Surf when they generally succeed, hardly ever being

foiled in more than one attempt."

The most dramatic

feature of this account, the sentence may indicate that if the rider is

unable to maintain a position on the wave face ("fail in trying to

get before the surf") they may be caught and enveloped in the white-water

- "in such a tremendous wave ... impossible for any human being

to live in it".

At an extreme (certainly

not fully confirmed by the text), this section could be interpreted see

as the first description of a "tube-ride" or "cover up".

Modern Boogie riders

frequently ride so far back in the curl that the impact zone eventually

propels the rider out the back of the wave - "they rise on the other

side".

Despite Samwell's

practical assessment of the intrinsic danger of the activity ( see Note

14, below), the rider's treat the situation with disdain - "laughing

and shaking their Locks".

13. "Thus these

People find one of their Chief amusements"

Given the generality

of this comment, it may indicate that Samwell had previously viewed

the activity and/or that he had heard other reports by members of the crew.

14. "young

boys & Girls about 9 or ten years of age"

Samwell attempts

to specifically estimate the age of some of the participants, see Note

1.

15. "no other

than certain death."

Certainly for a

18th century European, who probably could not swim, the activity was extreme.

The inherent danger

of the activity is often overlooked by surf-experienced commentators.

16. "So true

it is that ... Perseverance."

Samwell draws a

philosophical conclusion.

DAVID SAMWELL

"David Samwell

sailed on the Third Voyage on the Resolution as Surgeon's mate, later transferring

to the Discovery.

He was born

in Nantglyn, Wales in 1751 and died in London in 1798.

Prior to his

death he had been a surgeon to British troops at Versailles in France.

Samwell kept

a journal on the Third Voyage, which contains one of the most detailed

descriptions of the events surrounding Cook's death.

He was also

a respected poet who wrote verse in English and Welsh and was honoured

at eisteddfods.

There is a

short biography of him in the Dictionary of National Biography (vol.17,

p.732)."

Beaglehole, John

C. (editor) : The Voyage of the Resolution and Discovery 1776 - 1780.

Cambridge Hakluyt

Society, Two Volumes.

Volume 1, page 268.

1967.

Reprinted in Finney,

Ben and Houston, James D. :

Surfing

– A History of the Ancient Hawaiian Sport. 1996. Appendix B. Page

97.

Page 592.

These Plantations

in many places they carry six or seven miles up the side of the hill, when

the woods begin to take place which diffuse themselves from hence to the

heights of the eminences and extend over a prodigious track of ground;

in these woods are some paths of the Natives and here and there a temporary

house or hut, the use of ...

Page 593.

which is this; when a man wants a Canoe he repairs to the wood and

looks about him till he has found a tree fit for his purpose and a convenient

spot for his work; having succeeded thus far, he runs up a house for his

present accommodation and goes to work upon his Canoe, which they in general

compleatly finish before it's moved from the spot where its materials had

birth.

Our people who made excursions about the Country saw many of these

Canoes in different states of forwardness, but what is somewhat singular,

if one of their vessels want repairing she is immediately removed into

the woods though at the distance of 5 or 6 miles.

<...>

These people are exceedingly populous; the day we went first into

Care'ca'coo'ah Bay there were counted about the Resolution 500 Canoes and

about the Discovery 475, a great many of these were large double Boats

carrying ten or twelve Men so that here was a vast concourse of People;

however many of these were assembled from various parts of the Isle, and

some I know came from the Isle of Mow'wee, but the immense number of Men

and women living in the various villages about this Bay surpassed every

idea of populousness I could ever form, and the abundant stock of Children

promised very fairly a plentiful supply for the next Generation.

"But a diversion the most common is upon the Water, where there is a very great Sea, & surf breaking on the Shore.

The Men sometimes 20 or 30 go without the Swell of the Surf, & lay themselves flat upon an oval piece of plank about their Size & breadth (1), they keep their legs close on top of it, & their Arms are us'd to guide the plank, they wait the time of the greatest Swell that sets on Shore, & altogether push forward with their Arms to keep on its top (2), it sends them in with a most astonishing Velocity & the great art is to guide the plank so as always to keep it in a proper direction on the top of the Swell, & as it alters its directn (3).

If the Swell drives him close to the rocks before he is overtaken by its break; he is much prais'd.

On first seeing this very dangerous diversion I did not conceive it possible but that some of them must be dashed to mummy against the sharp rocks, but just before they reach the shore, if they are very near, they quit their plank, & dive under till the Surf is broke, when the piece of plank is sent many yards by the force of the Surf from the beach.

The greatest number are generally overtaken by the break of the swell, the force of which they avoid, diving & swimming under the water out of its impulse.(4)

By such like excercises, these men may be said to be almost amphibious.

The Women could swim off to the Ship, & continue half a day in the Water, & afterwards return.

The above diversion is only intended as an amusement, not a tryal of Skiil, & in a gentle swell that sets on must I conceive be very pleasant, at least they seem to feel a great pleasure in the motion which this Exercise gives. (5)"

NOTES

In the unedited

version, a close reading indicates that King has understood and related

...

1. "an oval

piece of plank about their Size & breadth"

Notes a shaped the

nose and maybe tail, the dimensions are difficult to estimate.

Probably not longer

than the rider's height, this width could vary from 15'' to 20'' for adult

riders.

They may have approximated

six feet long and by eighteen inches wide (6ft x 18'').

2. The

necessary dynamics of wave selection and the critical nature of take-off

positioning ..

"wait the

time of the greatest Swell ...(and) push forward with their Arms to keep

on its top"

3. The necessary

dynamics of positioning the board in the correct planning angle on the

wave face ..

"the great

art is to guide the plank so as always to keep it in a proper direction

on the top of the Swell."

Subsequent accounts

also confirm the neccessity of adjusting the board to the

correct planning angle on the wave face for successful surf-riding.

This was noted by

Blake

(1935, pages 41 - 42. ) and Finney

and Houston (1966, page ?) as strong evidence that the ancient

Hawaiians rode waves, in this respect, in exactly the same manner as (their)

contemporary surf-riders.

4. The method

of negotiating the difficulty of paddling out through the surf...

"the force

of which they avoid, diving & swimming under the water out of its impulse."

5. The excitement

and exhilaration of the activity ....

"they seem

to feel a great pleasure in the motion which this Exercise gives."

JAMES KING R.N.

These extracts,

dated March 1779, are taken from two published versions of the expedition's

log.

For the first account

of a previously unencounted and dynamically difficult activity, the information

of the combined versions is remarkable.

It clearly demonstrates

the powers of observation and critical analysis required by an officer

in the British navy in the 18th century and an appreciation of skilled

maritime activity.

King's account is

probably based on examining the surf-riding on a number of occasions.

It is possible that

on occasion, King's observations were from a boat on the water.

There are significant

differences in the two accounts.

Finney

and Houston (1996) caution that

"... the official

publication ... was heavily edited by ... Douglas ... adding marterial

of his own and from other accounts of the voyage." - Footnote,

Page 32.

Given that the additional

details of the edited version closely correspond with modern surf-riding

experience, in this case the information is unlikely to be from Douglas'

imagination and more likely from other eye-witness sources.

Cook, James and King,

James :

A Voyage to the

Pacific Ocean Undertaken by Command of his Majesty For Making Discoveries

in The Northern Hemisphere Performed Under Captains Cooke, Clerke, Gore

in Years 1776, 1777, 1778, and 1780, being a copious and Satisfactorary

Abridgement.

Douglas, Reverend

John (editor)

G. Nicholl and T.

Cadell, London, page ?. 1784.

Second Edition

A New, Authentic

and Complete Collection of Voyages Round the World, Undertaken and Performed

by Royal Authority. Containing an Authentic, Entertaining, Full, and Complete

History of Capt. Cook's First, Second, Third and Last Voyages

Anderson, George

William (editor).

(London, 1784-1786).

Translations

Neueste Reisebeschreibungen;

oder, Jakob Cook's dritte und letzte Reise . . . in den Jahren 1776 bis

1780. (Nuremberg, 1786). [An example of many translated versions.]

Reprinted in Finney,

Ben and Houston, James D. :

Surfing

– A History of the Ancient Hawaiian Sport. 1996. Chapter 3. Page

32.

The first wave they meet, they plunge under, and suffering it to rollover them, rise again beyond it (3), and make the best of their way, by swimming, out into the sea.

The second

wave is encountered in the same manner with the first ...

As soon as

they have gained by these repeated efforts, the smooth water beyond the

surf, they lay themselves at length on their board, and prepare for their

return.

As the surf consists of a number of waves (4), of which every third is remarked to be always much larger than the others, and to flow higher on the shore, the rest breaking in the intermediate space, their first object is to place themselves on the summit of the largest surge ....

If by mistake

they should place themselves on one of the smaller waves, which breaks

before they reach the land, or should not be able to keep their plank in

a proper direction on the top of the swell,

they are left

exposed to the fury of the next, and, to avoid it, are obliged again to

dive and regain their place, from which they set out. (5)

Those who succeed

in their object of reaching shore, have still the greatest danger to encounter.

The coast

being guarded by a chain of rocks, with, here and there, a small opening

between them, they are obliged to steer their boards through one of these

(6),

or, in case of failure, to quit it, before they reach the rocks, and, plunging

under the wave., make the best of their way back again.

This is reckoned very disgraceful, and is also attended with the loss of the board, which I have often seen, with great horror, dashed to pieces, at the very moment the islander quitted it. (7)"

NOTES

The edited version

notes ...

1. The challenge

of extreme conditions ..

"Whenever

... the impetuosity of the surf is increased to its utmost heights, they

choose that time for their amusement,"

2. "a long

narrow board, rounded at the ends"

Vague and indeterminate

dimensions, but notes shaped the nose and maybe the tail.

3. A sophisticated

method of negotiating the (breaking) wave zone by a co-ordinated submerging

of board and

body through the

base of an approaching wave.

In contemporary

surf-riding this is known as a "duck-dive".

Although commonly

used by body-surfers, it is more difficult when attempted with a board.

"The first

wave they meet, they plunge under, and suffering it to rollover them, rise

again beyond it ..."

4. The recognition

that waves come in 'sets' ...

"As the surf

consists of a number of waves"

5. The difficulties

of miscalculation in wave selection, resulting in "getting it on the head"

...

"by mistake

they should place themselves ..., they are left exposed to the fury of

the next"

6. The potential

danger to the rider and the difficulty in negotiationing a rocky shoreline

to return safely to the beach ...

"The coast

being guarded by a chain of rocks ... they are obliged to steer their boards

through".

7. The

potential danger to the rider and the board if they are separated ...

"the loss

of the board ... dashed to pieces, at the very moment the islander quitted

it."

|

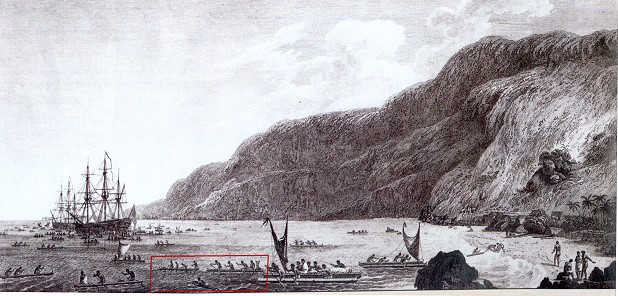

Detail from John Webber : A View of KaraKakooa, in Owyhee. An engraving based on an original drawing at Kealakekua Bay, 1779. Printed in the official account of the voyage, Plate 68. See reference below. |

Resolution

and Discovery, the ships of James Cook's third Pacific expedition,

initially anchored and landed at Waimea River mouth, Kaui on 20th January

1778, staying for four days.

Finney

and Houston (1996), page 31, identify three ancient surf-riding

sites at Waimea River mouth, Kauai.

Departing on 24th

January, the next anchorage and landfall was near Leahi Point on the island

of Nihau on 29th January 1788.

After a further

stay of approximately four days, Cook left on 2nd February 1778 to explore

the North West Pacific.

Finney

and Houston (1996) identify one ancient surf-riding site

near Leahi Point, Nihau, page 31.

Cook's expedition

returned to the Hawaiian Islands on 26th November 1778.

Without landing,

he met with Kalani'opu'u (the king of the island of Hawaii) off the coast

of Maui near Kahului on the following day and subsequently set sail for

the big island.

The prevailing weather

conditions and the failure to locate an anchorage suitable to Cook's requirements,

delayed a landing until 16th January 1789.

The arrival in Kealakekua

Bay, Hawaii was greeted by over a thousand canoes as illustrated by John

Webber's "A View of KaraKakooa, in Owyhee, 17 January 1779."

This is the first

European depiction of a surf-board. See below.

Finney

and Houston (1996) identify one ancient surf-riding site

specifically at Kealakekua Bay, Hawaii.

Furthermore, they

identify another thirty two ancient sites within approximately 30 kilometres

(23 miles) of Kealakekua Bay, pages 28 and 29.

After an extended

stay of nineteen days, the ships left Kealakekua Bay on 4th February 1779.

Unfortunately for

Cook, Resolution's mast broke after two days sailing and he was

forced to return to on the 11th February.

Simmering cultural

differences resulted in a violent confrontation on the 14th February wherein

Cook, and twenty-one others, died.

Command of the expedition

fell to Charles Clerke, previously the captain of the Discovery,

who was able to restore relations.

Clerke determined

that he should continue to fulfil Cook's orders and the expedition left

Kealakekua Bay for the North Pacific on 22nd February, 1779.

The return necessitated

by Resolution's broken mast lasted eleven days, which brings to

a total of thirty days that Lt. King spent in and around Kealakekua Bay,

Hawaii.

The next anchorage

was three weeks later at Waimea Bay, Ohau, on the 27th February, but was

only for one night and they sailed west on the 28th.

Finney

and Houston (1996), page 38, identify one ancient surf-riding

site specifically at Waimea Bay, Ohau.

On the 2nd March

1779, the expedition returned to its previous anchorage at Waimea Bay on

Kaui.

Relations were strained

(mostly due to local problems) and after a stay of six days, Clerke relocated

to the previously used anchorage off Leahi Point, Nihau on the 8th March.

This was the final

landfall in the Hawaiian Islands, a stay of five days.

The expedition departed

for Kamchatka on the 15th March, 1779.

In total the ships

of Cook's third pacific expedition were anchored in Hawaiian waters for

49 days.

The longest was

at Kealakekua Bay, Hawaii (30 days) but much of the return visit would

have been preoccupied with Cook's violent death and its aftermath.

It would appear

that Lt King's observations were most probably at, or around, Kealakekua

Bay.

Note that there

are no reports from Hilo Bay on Hawaii or Wakiki on Ohau, apparently the

two major centres of ancient Hawaiian surf-riding.

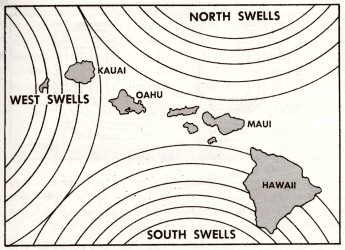

Also note that at

this time of the year the predominant swell direction is the famed winter

swells originating in the North Pacific, and the extended anchorage's were

all on the southern coasts.

Generally, the southern

coasts best surf-riding conditions are with the summer swells from the

southern ocean, although some may also be exposed to winter swell from

the west. See below.

If the Kona coast

surf-riders had been questioned as to the suitability of the conditions,

their response may have translated as approximately ...

The one northern

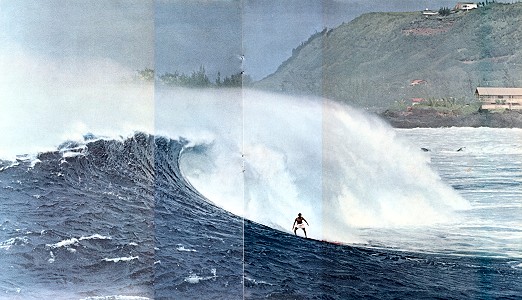

anchorage, at Waimea Bay on the island of Ohau, was only for one night

(27 - 28 February 1779).

Given the modern

reputation of this location for big wave surf-riding at this time of the

year, it appears that Clerke's decision to relocate to Waimea Bay on Kaui

was sensible. See below.

|

Wright (1971) page 9. Illustration by Bill Penarosa |

The one northern

anchorage, at Waimea Bay on the island of Ohau, was only for one night

(27 - 28 February 1779).

Given the modern

reputation of this location for big wave surf-riding at this time of the

year, it appears that Clerke's decision to relocate to Waimea Bay on Kaui

was sensible. See below.

Reference

The above details

of Cook's voyages were largely collated from Robson(2000).

This is a unique

work with a wealth of information in the form of maps, providing a wonderful

geographical context to Cook's voyages that is simply not possible from

written accounts.

Information specifically

relevant to Hawaii was selected from pages 154 to 155, pages 159 to 160

and the maps 3.12, 3.23, 3.24 and 3.25.

The Reports

Three excerpts are

attributed to surgeons - Anderson, Ellis and Samwell.

Two reports are

by naval officers Clerke and King, and one by a midshipman, GeorgeGilbert.

The journalists

served on

The final report,

attributed to King, is a construction by Rev. Douglas and bears little

relationship to King's report in Beaglehole (1967).

The locations are

also diverse

Clerke's report

of canoe surfing from Tahiti

The Format

I have attempted

to note the earliest publication of each extract and any subsequent reproduction.

These are not exhaustive.

The rank of the crew

members is given at the time of their report.

Note that after

Cook;s death there was a re-allocation of duties on both vessels.

I have made an attempt

to note the possible locations of the accounts, essentially by correlating

Finney

and Houston (1966) and Robson(2000).

An extended analysis

is included at Surf-riding Locations.

The quotations have their original spelling and grammar, however I have spaced each sentence to be consistent with my preferred monitor presentation (as illustrated here).

The biographical

notes are brief, with a focus on the the history of the publication.

I would like to

thank Alan Twigg, British Columbia,

for permission to quote from his extensive notes.

Where applicable, I have included some comments noting the research thread.

THE VOYAGES OF

JAMES COOK R.N.

James Cook lead

three scientific and exploratory expeditions to the Pacific Ocean for the

British Navy, from 1768 to 1780.

His achievements

were considerable.

The first voyage

(1768-1771), in the Endeavour, recorded the transit of Venus from

Tahiti, circumnavigated New Zealand and established the extent of the east

coast of Australia.

This largely disproved

a prevalent theory, Terra Australis incognita, of a massive southern

continent - ostensibly to balance those of the northern hemisphere.

The voyage was expertly

recorded (note Cook's superb mapping techniques) and returned a huge collection

of cultural and botanical specimens, largely due to Joseph Banks and Dr

Solander.

These elements were

also features of the subsequent voyages.

The second voyage

(1772 - 1775), in the Resolution accompanied by the Adventure,

firmly located the known islands of the Pacific ocean and discovered several

others.

It was probably

the first voyage below the Antarctic Circle and was terminal for the theory

of Terra Australis incognita.

The voyage emphatically

proved the worth of John Harrison's

maritime chronometer to calculate longitude and set new standards of naval

health care - of four deaths, only one crew member died of sickness.

Cook recognized

Polynesia as a distinct cultural entity and largely defined its massive

spread across the Pacific.

The third voyage

(1776 - 1780), also in the

Resolution but now accompanied

by the Discovery,

failed to locate the North West Passage but in

the process an extensive area of the North Pacific coasts was explored

and mapped.

Further Pacific

islands were discovered, notably the Hawaiian islands, where Cook would

be killed at Kealakekua Bay, Hawai'i on the 14th February 1779.

Command of the expedition

and the Resolution fell to Charles Clerke, the captain of the Discovery

who had sailed with Cook on his previous two Pacific voyages.

Lt. James King of

the Resolution was promoted to first lieutenant.

John Gore, Cook's

first lieutenant who had sailed on the Endeavour, took command of

the Discovery.

Other crew members of the Resolution included artist John Webber and Master William Bligh.

Clerke determined

that he should continue to fulfil Cook's orders and leaving Hawaii in March

1779, the expedition returned to the North Pacific.

Charles Clerke died

at sea on the 21st August 1779 and Gore took command of the Resolution

with King taking command of the Discovery.

Following the return

to England on the 4th October 1780, King was selected to edit the logs

and journals to prepare them for publication.

Reference

The above details

of Cook's voyages were largely collated from Robson(2000).

This is a unique

work with a wealth of information in the form of maps, providing a wonderful

geographical context to Cook's voyages that is simply not possible from

written accounts.

Information specifically

relevant to Hawaii was selected from pages 154 to 155, pages 159 to 160

and the maps 3.12, 3.23, 3.24 and 3.25.

THE PUBLICATION

OF COOK'S JOURNALS

"Usually cited

as the first European to set foot in British Columbia, James Cook posthumously

published the fifth earliest account in English of the first British landing

in British Columbia.

...

The British

Admiralty published an edited account of Cook’s voyages in three quarto

volumes and a large atlas in 1784-1785, now generally known as 'A Voyage

to the Pacific Ocean'.

The journals

were heavily edited by Dr. John Douglas, Bishop of Salisbury.

As commissioned

by the Lords of the Admiralty, Douglas embellished much of Cook’s original

journals with material gleaned from Cook’s officers.

In particular,

Douglas extrapolated from Cook’s reports of ritualistic dismemberment among

the Nootka, beginning the belief that the Indians engaged in cannibalism

when Cook had, in fact, described them as “docile, courteous, good-natured

people.”

Some of the

more sensational revelations added to the text were designed to encourage

the spreading of “the blessings of civilization” among the heathens and

to help sell books.

For almost

200 years Douglas’ version of Cook’s writings was erroneously accepted

as Cook’s own. Cook’s journal, with its bloody ending supplied by James

King, proved popular.

Within three

days of its publication in 1784, the first printing was sold out.

There were

five additional printings that year, plus 14 more by the turn of the century.

Translations

were made throughout Europe.

The original

version of Cook’s journal was edited by J.C. Beaglehole and finally published

for scholars in the 1960s.

It reveals

that Cook was a somewhat dull reporter, more interested in geography than

anthropology.

The profits

from the publication of Cook’s journals went to the estates of Cook, James

King and Charles Clerke (Commander of the Discovery), with a one-eighth

share for William Bligh, master of the Resolution, because his surveying

work was so essential.

The irascible

Bligh wrote in ink on the title page of his own copy, 'None of the Maps

and Charts in this publication are from the original drawings of Lieut.

Henry Roberts, he did no more than copy the original ones from Captain

Cook who besides myself was the only person that surveyed and laid the

Coast down, in the Resolution. Every Plan & Chart from C. Cook’s death

are exact copies of my works.'”

Please pass this along as a response to Geoff Cater on early historical accounts of surfing.

In the course

I teach on surf history and culture (at Drury University), and in an anthology

that I've been putting together based on this course, I've come across

a number of these early accounts by Cook's mariners.

Several (including

the one you cite from David Samwell) can be found in the multi-volume _The

Journals of Captain

James Cook on his Voyages of Discovery_ edited by J.C. Beaglehole (Cambridge

UP, 1955-67).

Samwell's entry dates from January 22, 1779, and so possibly precedes King's, whose description takes place between their arrival on January 18 and their departure in March.

Besides the entries by Joseph Banks on Cook's first voyage (which Joe passed along not too long ago) and the famous description of Tahitian canoe riding by William Anderson (not James Cook) on Cook's third voyage, here are several more that may be of interest.

The earliest reference to surfridng appears to be from Charles Clerke, who took command of the Resolution after Cook's death. When Cook first touched in the Islands in 1778, Clerke registered the following comments at either Waimea, Kauai or Kamalino, Ni'ihau between January 19 and February 2, 1778:

"These People handle their Boats with great dexterity, and both Men and Women are so perfectly masters of themselves in the Water, that it appears their natural Element; they have another convenience for conveying themselves upon the Water, which we never met with before; this is by means of a thin piece of Board about 2 feet broad & 6 or 8 long, exactly in the Shape of one of our bone paper cutters; upon this they get astride with their legs, then laying their breasts along upon it, they paddle with their Hands and steer with their Feet, and gain such Way thro' the Water, that they would fairly go round the best going Boats we had in the two Ships, in spight of every Exertion of the Crew, in the space of a very few minutes. There were frequently 2 and sometimes upon one of these peices of board, which must be devilishly overballasted; still by their Management, they apparently made very good Weather of it."

Also in January

of 1778, William Ellis (Surgeon's Mate) recorded the following entry at

Waimea, Kauai (from An Authentic Narrative of a Voyage Performed by Captain

Cook and Captain Clerke in His Majesty's Ships Resolution and Discovery

(1782))

"Their canoes

or boats are the neatest we ever saw, and composed of two different coloured

woods, the bottom being dark, the upper part light, and furnished with

an out-rigger. Besides these, they have another mode of conveying

themselves in the water, upon very light flat pieces of boards, which we

called sharkboards, from the similitude the anterior part bore to the head

of that fish. Upon these they will venture into the heaviest surfs,

and paddling with their hands and feet, get on at a great rate. Indeed,

we never

saw people so

active in the water, which almost seems their natural element."

In February of

1779 (I'm assuming at Kealakekua Bay), Midshipman George

Gilbert recorded

this observation (from Captain Cook's Final Voyage: The Journal of Midshipman

George Gilbert (1982)):

"Several of those

Indians who have not got Canoes have a method of swimming upon a piece

of wood nearly in the form of a blade of an oar, which is about six feet

in length, sixteen inches in breadth at one end and about 9 at the other,

and is four or five inches thick, in the middle, tapering down to an inch

at the sides.

They lay

themselves upon it length ways, with their breast about the centre; and

it being sufficient to buoy them up they paddle along with their hands

and feet at a moderate rate, having the broad end foremost; and that it

may not meet with any resistance from the water, they keep it just above

the surface by weighing down upon the other, which they have underneath

them, betweeen their legs. These pieces of wood are so nicely balanced

that the most expert of our people at swimming could not keep upon them

half a minuit without

rolling off."

This last observation at leasts suggests that some of Cook's men may have tried paddling (or surfing?) on these boards themselves.

At any rate, the presence of these journal entries (more than have been noted in histories of Surfing) emphasizes (at least to my mind) the great fascination these mariners had with surfboards and surfing. Their detailed accounts of surfboard sizes, shapes, and purpose is an important (and mostly undiscovered) link in why and how surfing manages to survive when so many other native pasttimes did not.

All the best,

Patrick Moser.

Reply

I replied, mostly

detailing historical details that have been added to the above paper.

In response to Patrick's

final paragraph, I wrote ...

At any rate, the presence of these journal entries (more than have been noted in histories of Surfing) emphasizes (at least to my mind) the great fascination these mariners had with surfboards and surfing. Their detailed accounts of surfboard sizes, shapes, and purpose is an important (and mostly undiscovered) link in why and how surfing manages to survive ...

Very interesting ... I can only make some disjointed observations that may relect on this ...

More than a maritime

culture - an aquatic culture.

As mariners, the

journalists had a fascination with all things nautical - there are extensive

accounts that relate to canoes, seamanship and navigation.

Specifically, Cook

was amazed that the Hawaiians were there before he was and was the first

to suggest that Polynesian settlement was the result of extensive voyages

from the west - a feat that preceded his own voyages.

Given that some (unknown

proportion) of the crew could not swim at all (Cook and, I think, King

and note 7. above), Hawaiian familiarity with the ocean, where swimming

was a basic community skill, must have been impressive.

Obscure thought

- Could Cook have saved himself, if he was able to swim?

The origins of modern

swimming are difficult to ascertain - a restricted amount of research has

indicated to me that the development of the common crawl stroke (the Olympic

freesyle) has at least some import from Polynesian, especially Hawaiian,

swimming.

I would propose

that there is a technical relationship between 'native' swimming and board

paddling - the combined overarm stroke and flutter kick.

If this conjecture

has any validity, then (as Hawaiian surf-riding has now expanded across

all the world's oceans) Polynesian swimming has now expanded across the

world's oceans, lakes and swimming pools.

Surf-riding conditions

and locations

Confident of their

skills, the Hawaiians chose the most extreme conditions ( 'great swell'

-Samwell) for their 'diversion'.

Even in Hawaii,

good surf-riding conditions are not consistant, sublime conditions are

rare, large and sublime conditions even rarer.

If Cook had not

had extended stays, or if social relations had been mostly confrontational,

then we may not have these accounts.

However, note that

these accounts of prone riding seem mostly derive from Kealakekua Bay,

Hawaii.

Although this was

probably the most populous area, at this time (winter) the bay was protected

from the prominant swell direction from the north.

A significant number

of Hawaiian legends (see Finney (1996), Chapter 3) indicate that (the now

extinct) Hilo Bay, on the opposite coast of Hawaii, was a centre of surf-riding

excellence and exposed to the winter north swells, but none of the 1779

reports indicate knowledge of this.

The other legendary

centre was Waikiki, Oahu - exposed to the summer south swells and protected

from the north.

Photographic evidence

(Edison, circa 1905) confirms that the surf-riding conditions of Wakiki

for solid wood finless boards can be sublime.

If Cook was searching

for surf, then probably "he really missed it - he should have been there

six months ago!" (paraphasing Brown, 1966).

The wave as icon

For each riding

location ('surf break') there are specific features of paddle-out, take-off

and the general wave characteristics.

For each individual

wave another specific set of variables is operational.

Each wave (an animated

expression of climatic forces?) is structually, aesthetically and temporaly

unique in nature.

An early representation

of the wave as icon is Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) : Under the wave

off Kanagawa c.1825?1831?

The wave as icon

retains its attaction in contemporary times - evidenced by the number of

photographs of riderless wavescapes that are regulary printed.

Surf-riding, wave-riding,

surf-shooting, wave-sliding, he'e nalu

Finney's list of

traditional Hawaiian riding and wave terminology (1996, Appendix A) and

the early written reports appear to confirm that traditional riders transversed

the wave face in the same manner as all subsequent riders.

The mechanics of

this are both highly complex (that is, I don't understand them) and highly

variable.*

For Cook's crew,

surf-riding was like no other previous experienced human activity - it

was unique.

In my opinion it

is still the case that surf-riding is an unique human activity.

*I have made one

(poor) attempt to deal with this problem ...

http://www.surfresearch.com.au/a_surfboard_dynamics.html

The surfboard

The Hawaiians further

advanced their activity by the development of specific craft to maximize

their wave-riding performance.

Board construction

was a combination of highly developed craftsmanship and an access to a

rich source of building materials - specifically the massive koa forests

of the Hawaiian islands.

This is easily seen

in the accounts of the number, the size and the quality of workmanship

of Hawaiian canoes.

The earliest surboards were hand-shaped objects (a sculpture) and despite the application of modern technologies, the basic surfboard retained hand-shaping at least until the end of the twentith century.

when so

many other native pasttimes did not.

Most native pastimes

had some European equivalent - board games, wrestling, running, sailing,

dance.

Hawaiian surf-riding

was a highly developed unique activity - and the waves are still there.

The Reports

Three excerpts are

attributed to surgeons - Anderson, Ellis and Samwell.

Two reports are

by naval officers Clerke and King, and one by a midshipman, GeorgeGilbert.

The journalists

served on

The final report,

attributed to King, is a construction by Rev. Douglas and bears little

relationship to King's report in Beaglehole (1967).

The locations are

also diverse

Clerke's report

of canoe surfing from Tahiti

The Format

I have attempted

to note the earliest publication of each extract and any subsequent reproduction.

These are not exhaustive.

The rank of the crew

members is given at the time of their report.

Note that after

Cook;s death there was a re-allocation of duties on both vessels.

I have made an attempt

to note the possible locations of the accounts, essentially by correlating

Finney

and Houston (1966) and Robson(2000).

An extended analysis

is included at Surf-riding Locations.

The quotations have their original spelling and grammar, however I have spaced each sentence to be consistent with my preferred monitor presentation (as illustrated here).

The biographical

notes are brief, with a focus on the the history of the publication.

I would like to

thank Alan Twigg, British Columbia,

for permission to quote from his extensive notes.

Where applicable, I have included some comments noting the research thread.

THE VOYAGES OF

JAMES COOK R.N.

James Cook lead

three scientific and exploratory expeditions to the Pacific Ocean for the

British Navy, from 1768 to 1780.

His achievements

were considerable.

The first voyage

(1768-1771), in the Endeavour, recorded the transit of Venus from

Tahiti, circumnavigated New Zealand and established the extent of the east

coast of Australia.

This largely disproved

a prevalent theory, Terra Australis incognita, of a massive southern

continent - ostensibly to balance those of the northern hemisphere.

The voyage was expertly

recorded (note Cook's superb mapping techniques) and returned a huge collection

of cultural and botanical specimens, largely due to Joseph Banks and Dr

Solander.

These elements were

also features of the subsequent voyages.

The second voyage

(1772 - 1775), in the Resolution accompanied by the Adventure,

firmly located the known islands of the Pacific ocean and discovered several

others.

It was probably

the first voyage below the Antarctic Circle and was terminal for the theory

of Terra Australis incognita.

The voyage emphatically

proved the worth of John Harrison's

maritime chronometer to calculate longitude and set new standards of naval

health care - of four deaths, only one crew member died of sickness.

Cook recognized

Polynesia as a distinct cultural entity and largely defined its massive

spread across the Pacific.

The third voyage

(1776 - 1780), also in the

Resolution but now accompanied

by the Discovery,

failed to locate the North West Passage but in

the process an extensive area of the North Pacific coasts was explored

and mapped.

Further Pacific

islands were discovered, notably the Hawaiian islands, where Cook would

be killed at Kealakekua Bay, Hawai'i on the 14th February 1779.

Command of the expedition

and the Resolution fell to Charles Clerke, the captain of the Discovery

who had sailed with Cook on his previous two Pacific voyages.

Lt. James King of

the Resolution was promoted to first lieutenant.

John Gore, Cook's

first lieutenant who had sailed on the Endeavour, took command of

the Discovery.

Other crew members of the Resolution included artist John Webber and Master William Bligh.

Clerke determined

that he should continue to fulfil Cook's orders and leaving Hawaii in March

1779, the expedition returned to the North Pacific.

Charles Clerke died

at sea on the 21st August 1779 and Gore took command of the Resolution

with King taking command of the Discovery.

Following the return

to England on the 4th October 1780, King was selected to edit the logs

and journals to prepare them for publication.

Reference

The above details

of Cook's voyages were largely collated from Robson(2000).

This is a unique

work with a wealth of information in the form of maps, providing a wonderful

geographical context to Cook's voyages that is simply not possible from

written accounts.

Information specifically

relevant to Hawaii was selected from pages 154 to 155, pages 159 to 160

and the maps 3.12, 3.23, 3.24 and 3.25.

THE PUBLICATION

OF COOK'S JOURNALS

"Usually cited

as the first European to set foot in British Columbia, James Cook posthumously

published the fifth earliest account in English of the first British landing

in British Columbia.

...

The British

Admiralty published an edited account of Cook’s voyages in three quarto

volumes and a large atlas in 1784-1785, now generally known as 'A Voyage

to the Pacific Ocean'.

The journals

were heavily edited by Dr. John Douglas, Bishop of Salisbury.

As commissioned

by the Lords of the Admiralty, Douglas embellished much of Cook’s original

journals with material gleaned from Cook’s officers.

In particular,

Douglas extrapolated from Cook’s reports of ritualistic dismemberment among

the Nootka, beginning the belief that the Indians engaged in cannibalism

when Cook had, in fact, described them as “docile, courteous, good-natured

people.”

Some of the

more sensational revelations added to the text were designed to encourage

the spreading of “the blessings of civilization” among the heathens and

to help sell books.

For almost

200 years Douglas’ version of Cook’s writings was erroneously accepted

as Cook’s own. Cook’s journal, with its bloody ending supplied by James

King, proved popular.

Within three

days of its publication in 1784, the first printing was sold out.

There were

five additional printings that year, plus 14 more by the turn of the century.

Translations

were made throughout Europe.

The original

version of Cook’s journal was edited by J.C. Beaglehole and finally published

for scholars in the 1960s.

It reveals

that Cook was a somewhat dull reporter, more interested in geography than

anthropology.

The profits

from the publication of Cook’s journals went to the estates of Cook, James

King and Charles Clerke (Commander of the Discovery), with a one-eighth

share for William Bligh, master of the Resolution, because his surveying

work was so essential.

The irascible

Bligh wrote in ink on the title page of his own copy, 'None of the Maps

and Charts in this publication are from the original drawings of Lieut.

Henry Roberts, he did no more than copy the original ones from Captain

Cook who besides myself was the only person that surveyed and laid the

Coast down, in the Resolution. Every Plan & Chart from C. Cook’s death

are exact copies of my works.'”

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

Volume 3

Chapter VII -- General Account of the Sandwich Islands Continued

AJ-130b-0158

Copyright & Access © Copyright 2003 by the Wisconsin Historical

Society (Madison, Wisconsin). For further information see http://www.americanjourneys.org/rights/

Page 145

Swimming is not only a necessary art, in which both their men and women are more expert than any people we had hitherto fees, but a favourite divert on amongst them. One particular mode, in which they sometimes amused themselves with this exercise, in Karakakooa Bay, appeared to us moft perilous and extraordinary, and well deserving a distinct relation.

The surf, which breaks on the coal round the bay, ex tends to the diftance of about one hundred and fifty yards from the shore, within which apace, the forges. of the fea, accumulating from the shallowness of the water, are dated against the beach with prodigious violence. Whenever, from stormy weather, or any extraordinary swell at sea, the impetuosity of the surf is increased to its utmost height, they choose

Page 146

... that time for this amusement, which is performed in the following manner: Twenty or thirty of the natives, taking each a long narrow board, rounded at the ends, set out together from the shore. The first wave they meet, they blunge under, and suffering it to roll over them, rise again beyond it, and make the best of their way, by swimming, out into the sea. The second wave is encountered in the same manner wiht the first; the great difficulty consisting in seizing the proper moment of diving under it, which, if missed, the person is caught by the surf, and driven back again with great violence; and all his dexterity is then required to prevent himself from being dashed against the rocks. As soon as they have gained, by these repeated efforts, the smooth water beyond the surf, they lay themselves at length on their board, and prepare for their return. As the surf sonsists of a number of waves, of which every third is remarked to be always much larger than the others, and to slow higher on the shore, the rest breaking in the intermediate space, their first object is to place themselves on the summit of the largest surge, by which they are friven along with amazing rapidity toward the shore. If by mistake they should place themselves on one of the smaller waves, which breaks before they reach land, or should not be able to keep their plank in a proper direction on the top of the swell, they are left exposed ot the fury of the next, and, to avoid it, are obliged again to dive and regain the place from which they set out. Those who succeed in their object of reaching the shore, have still the greatest danger to encounter. The coast being guarded by a chain of rocks, with, here and there, a small openin between them, they are obliged to steer their board through one of these, or, in case of failure, to quit it, before they reach the rocks,

Page 147

... and, plunging under the wave, make the best of their way back again. This is reckoned very disgraceful, and is also attended with the loss of the board, which i have often seen, with great terror, shred to pieces, at the very moment the islander quitted it. The boldness and address, with which we saw them perform these difficult and dangerous manoeuvres, was altogether astonithing, and is scarccly to be credited.*

An accident of which I was a near spectator, shews at how early a period they are fo far familiarized to the water, as both to lose all fears of it, and to fet its dangers at defiance. A canoe being overset, in which was a woman with children, one of them an infant, who, I am convinced, was not more than four years old, seemed highly delighted with what had happened, swimming about at its case, and playing a hundred tricks, till the canoe was put to rights again.

* and amusement, somewhat similar to this, at Otaheite, has been described Vol II page 150.