surfresearch.com.au

|

surfresearch.com.au

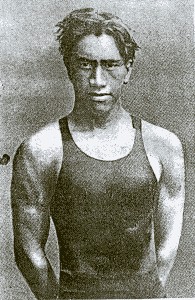

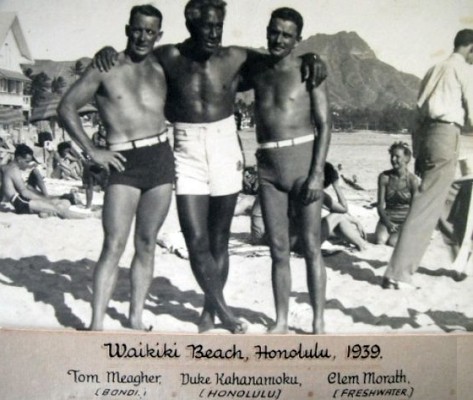

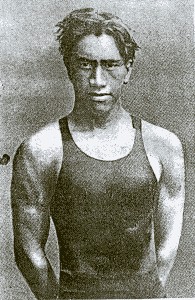

surfer : duke

kahanamoku

|

Duke

Kahanamoku

(1890 - 1968)

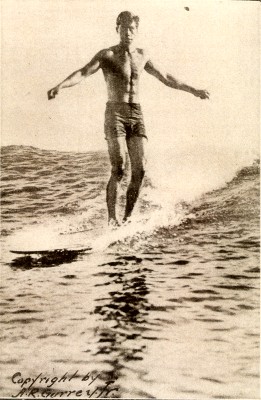

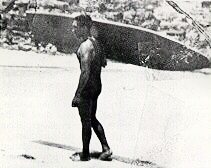

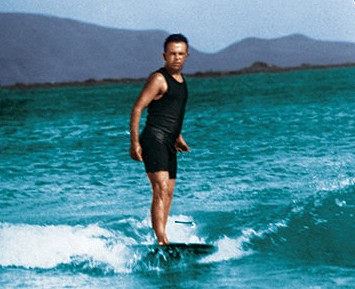

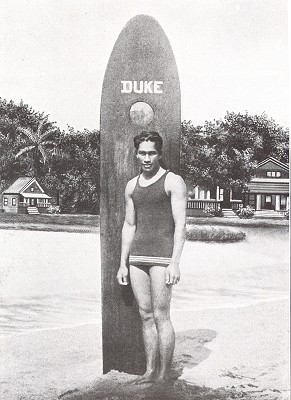

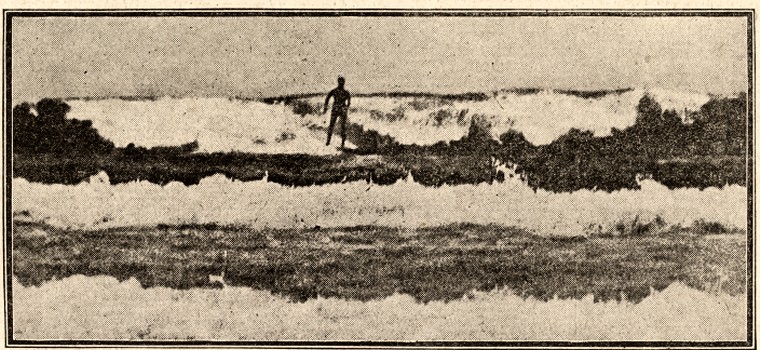

Duke Kahanamoku at Waikiki, 1910.

Selected items

from:

Newspaper

Menu : Surf and Surf-Bathing. Overview.

Following the

formation of the Outrigger Canoe Club in 1908 and the

acquisition of beach front property, its activities dominated

surf riding at Waikiki.

Among its

innovations were the Clark Cup contests, surf-board and

outrigger canoe riding competitions to be held in conjunction

with arrival of Frank C. Clark's cruise ship the Arabic

on two visits to Honolulu on the23rd January and 12th February,

1910

The first Clark

contest was plagued by a small swell and a brisk off-shore wind

and the surf riding competitions postponed.

Preparations for

the second Clark Cup included the construction of an Outrigger

Club float for the Floral Parade and the interest of a film

crew, led by M. Bonvillain of Pathe Freres, Paris

To assist in

shooing film of the contest, K.O. Hall &Son.provided

galvanised iron piping for a platform in the surf zone, which

was erected with considerable difficulty.

Bonvillain shot

some preliminary scenes of junior Outrigger members collecting

their boards from the grass houses and paddling out next to the Moana pier, these

included Lionel Steiner, Harold Hustace, Marston Campbell Jr.

and "Duke."

This is the

earliest report of Duke Kahanamoku in the Hawaiian press.

For images, See

DeLaVega: Surfing

in Hawaii (2011) page 70.

The February

contest was also to include a swimming race between the teams of

the Outrigger Club and the Diamond Head Athletic Club.

The Outrigger

team was Ben Vincent, Alfred Young, Cooper, Harry Steiner, Evans

and "Rusty Brown, captain.

The D. H. A. C.

was represented by D. Center, Glirdler, Duke, L. Cunha, C.

Oss, and Archie Robertson, captain.

Note that the

same report lists David Center and Duke Paua (in the B team, the

"Strawberry crew") as crews of Outrigger canoes in the six

paddle race.

At this time,

club membership appears flexible, with some competitors changing

from club to club or holding multiple memberships.

This regatta was

also plagued by a lack of swell and many events were cancelled.

In August, the

Promotion Committee considered several poster designs for the

upcoming floral parade.

The submitted

works were considered inappropriate, the press in stronger

words, described them as "the three atrocities."

One member

suggested an alternate design based on the image of a surf

rider, "which has been displayed here as an advertisement,"

which

was well received

by the committee.

This was,

presumably, the photograph of Duke Kahanamoku, taken and by A.

R. Gurrey Jr. and used in promoting his photographic studio.

A. R. Gurrey Jr.

published his widely reproduced company logo featuring Duke

Kahanamoku surfing at Waikiki in the Evening Bulletin

of 23rd

November, and two

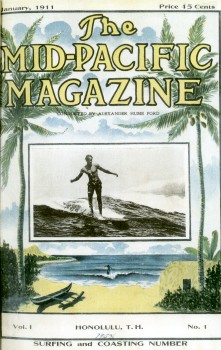

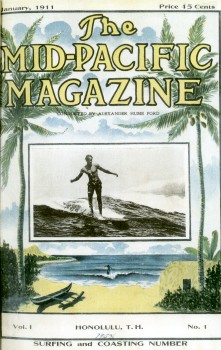

weeks later the newspaper announced the release of Alexander

Hume Ford's Mid-Pacific Magazine.

On 164 glossy

pages with halftone photographs, it represented a "high

standard in the printer's art" and it was claimed that it

would appear

simultaneously in

London, Boston, New York, San Francisco and Sydney.

1911

By the

end of 1910, Duke Kahanamoku had established a

reputation as one of Waikiki's leading expert surfboard

riders, such that the initial edition of Ford's Mid-Pacific

Magazine featured the first of a two-part

account of surfing, accredited to Duke Paoa, "the

recognized native Hawaiian champion surf rider."

The article was in fact written by Ford

The

introduction to the article noted:

"Duke

Paoa was born on the island of Oahu, within sound of

the surf, and has spent half of his waking hours from

early childhood battling the waves for sport.

He is

now 21 years of age, and is the recognized native

Hawaiian champion surf rider.

Duke

and the members of the Hui Nalu, an organization of

professional surfers at Waikiki, have supplied the

material for this article on the national sport of

Hawaii."

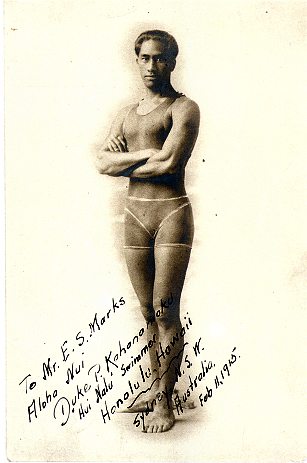

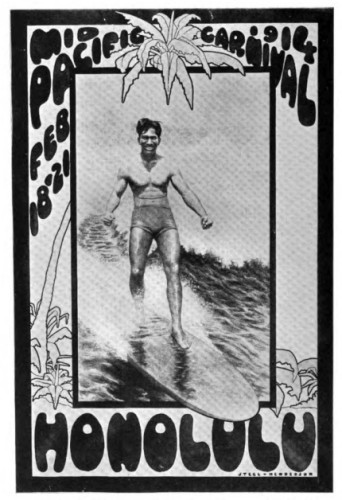

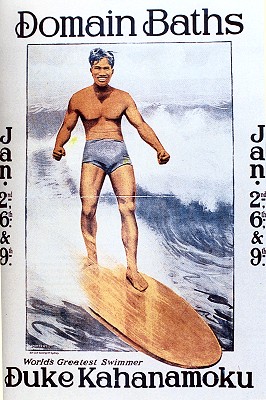

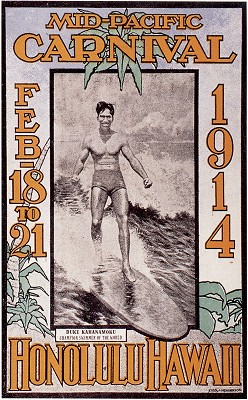

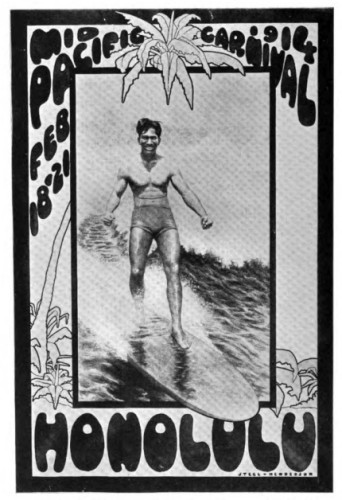

Significantly, the cover featured a photograph by

A.R. Gurrey of Duke

at Waikiki.

The image was also used to advertise Gurrey's

photographic studio in Honolulu and an illustration

based on the photograph was later used to promote

the Mid-Macific Carnival

(1914) and Duke's Australian tour in 1915.

|

|

The article

was supplemented by several surfboard riding photographs,

probably by the prolific A. R. Gurrey, and given the inclusion

of an article on Skiing in Australia by Percy

Hunter, it is likely that copies of the magazine were

available across the Pacific in Australia.

If a copy came

into the possession of one of the small number of Sydney

surfers, largely centred at Manly Beach, who were beginning to

experiment with Hawaiian type boards, then it would have been

highly prised and eagerly shown around that group.

See Kahanamoku, Duke Paoa: Riding the Surfboard.

The

Mid-Pacific Magazine, Honolulu, Volume 1, Number 1,

January,1911, page 3.

Around the middle

of the year, the Hui Nalu, described as "Waiklki rowers and

swimmers, composed chiefly of Hawaiians," was admitted to

the local branch of the A.A.U.

This new club was

largely an offshoot or a faction of the Outrigger Club, those

previously identified as Outrigger members included Duke Kahanamoku, Vincent

Genoves, Kenneth Winter and Curtis Hustace.

On the 5th

August, the Hui Nalu added twelve new members, making a total of

27.

E. K. Miller, W.

H. King and R. W. Foster were elected as their delegates to the

A.A.U.

The establishment

of the Outrigger Club, with its prime focus on contests in the

surf at Waikiki, allowed the wide program of events that

previously comprised the earlier Waikiki Regattas to be

diversified.

The rowing and

sailing races moved to the more suitable flat water of the

harbour and the swimming events, now under the auspices of the

A.A.U., to the slips between the docks where the length of the

course could be effectively measured.

The program for

the upcoming aquatic meet was released on the 8th August,

initially to be at the Bishop slip.

As the dock was

being used commercially on the day of the event, it was moved to

the Alakea slip.

.

Entrants from the

various clubs included Geo. Freeth and L. Cunha (Healani);

D. Center (Myrtle); and D. P. Kahanamoku and Vincent Genoves

(Hui Nalu).

Freeth's

eligibility was questioned, but after meeting with John Soper,

his application to join the A.A.U. was accepted.

The program did

not include a swimming team from the Outrigger Club, one

reporter suggesting that "the members got cold feet as soon

as the entry list of the Hui Nalus was scanned."

It later

transpired that the club had intended to enter a team, but due

to misadventure, if not "treachery", the correct documents were

not lodged before the official closing time.

Circumstantial

evidence suggested the involvement of the Hui Nalu in the

matter.

While the press

report suggested that disgruntled Outrigger members might

console themselves with that evening's moonlight dance in the

club's lanai, elsewhere on the same page it was noted that the

Hui Nalu club was "at present giving more attention to

swimming than dancing."

Any questionable pre-contest manoeuvres by the

Hui Nalu proved to be unnecessary, and the club emphatically

dominated the swimming races on the 12th

August.

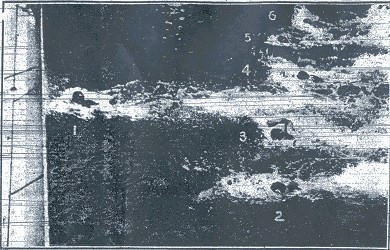

In excellent

conditions, the "water was as calm as a mill pond," Vincent

Genoves won the 440, the 880 yards and one mile and Duke

Kahanamoku won the 50, 100 and 220 yards events.

In addition,

Kahanamoku broke world record times for the 50 and 100 yards.

In a sudden leap

to international fame, the press noted that at the time Duke was

"not well known among the people of Honolulu, but is

remembered by many tourists who have visited Hawaii and taken

a dip in the surf of Waikiki."

As Hawaii's first

event sanctioned by the A.A.U., considerable care was taken to

correctly measure the course before the carnival and the events

were timed by several officials.

Due to some

cynicism as to the validity of these record breaking swims, the

course was re-measured the following day by a surveyor.

It was later

reported that it was, in fact, longer by one and a half feet;

however the records were not officially recognised at the time.

In a regular

column, Honolulu Newsletter published in the Maui

News in August, Oscar Brenton reviewed the failure

of the Outrigger Club to enter a team in the recent swim meet.

He implied that

the club, under the direction of Ford, had alienated a number of

junior members with its rigorous interpretation of amateur

status.

This probably

stemmed from the rejection of a motion to allow the payment of

juniors for providing canoe surfing services, passed at the AGM

on 15th February 1910.

As Duke

Kahanamoku "happens to get his livelihood making surfboards

and occassionally taking tourists canoing at so much a head",

under the rule he was unable to compete "for the Clark cups,

or anything else under the auspices of the Outriggers."

It is likely that

this dispute over the definition of amateur status within the

Outrigger Club significantly contributed to the formation of the

Hui Nalu in mid 1911.

Twelve months

later, the reasons for the defection of some Outrigger members,

notably Duke Kahanamoku, to the Hui Nalu were still considered a

mystery by most in Honolulu.

In July

1912, a reporter for the Honolulu Star-Bulletin

stated "many know, but more do not and the writer of

this is with the latter."

With an element

of regret, the article noted that it "would have been a good

thing from the point of view of the promoter of tourist travel

to the islands" for the international reputations of Duke

and the Outrigger Club to have been combined.

The regatta day

planned for the 12th September was to take place in Honolulu

harbour for a series of races for barges, ship's boats, shore

boats, whaleboats, and modern and old canoes.

There were also

sailing races for boats and canoes.

A barge race was

competed by groups of local government workers as Federal,

Territorial, or County Employees.

Visiting crews

included those of the Resolute, the Patterson,

and the Robert Searle.

Competing clubs

included the Healani Boat Club, the Myrtle Boat Club, the

Puunene Athletic Club, the K. A. C. Seniors, the Outrigger Club,

and the Hui Nalu.

The Hui Nalu

secured the A, Prince Kuhio's canoe, previously

used by the Kona paddlers, to compete in the six and four-paddle

canoe races.

Crew members

included lngworth, Duke Kahanamoku, O'Sullivan, Archie

Robertson, and Vincent Genoves.

They won both

canoe events, placing ahead of the Kamehameha's and the

Outrigger in the six paddle, and beating the K. A. C. Seniors in

the four-paddle race.

The event was

well attended with most support for the Healanis and the

Myrtles, but there were also a significant presence of the "black

and gold" for the Puunene Athletic Club and the "blue"

of the Hui Nalu.

The autumn of

1911 provided large waves at Waikiki.

At the end of

September canoe and board riders rode surf, said by experienced

elders, to be "higher today than at any time in the last nine

years."

Another

substantial swell arrived in November, which persisted for

several days and at one point was large enough to keep the local

fishing fleet at home.

1912

The New Year saw

steps to secure funds to send Duke Kahanamoku to the

mainland to take part in the Olympic trials.

About $230 was

already collected but the trip would require at least $1000, and

"an extra five hundred wouldn't hurt a little bit."

The reporter

noted the need of a manager/coach to avoid "the

wiles and wrinkles of important amateur athletic competitions"

and warned that suggestions by George Freeth that Duke seek

employment in California may prove detrimental to his amateur

status.

The Hui Nalu Club

arranged a dance on Saturday, January 27, at the Young roof

garden

Tickets were $4

each, the proceeds going to the Duke traveling fund.

At the time

swimming was the club's main focus, the press noting the "Hui

Nalu is not a rowing club at present."

In the first week

of February, Frederick Shaffer, a crewman of the visiting

cruiser Colorado, drowned at Waikiki while attempting to

rescue a woman in difficulties.

Shaffer's

companion and the woman were in turn rescued by the Outrigger's

youngest and most recent member, thirteen-year-old Ralph

Williams, Alexander Hume Ford and Duke Kahanamoku.

Williams and

Kahanamoku used their surfboards and Ford had grabbed in the

smallest outrigger canoe available.

Despite an

extensive search by Hui Nalu members and a search party raised

from the Colorado, Shaffer's body was not recovered that

day.

Ford later noted

that the Waikiki boys had regularly performed rescues, " the

Hustace boys with a score of life savings."

During the

following week, Duke Kahanamoku and Vincent Genoves gave

a free swimming exhibition in the Bishop slip before about 200

(?) spectators.

Although neither produced record breaking times,

they gave respectable performances under less than ideal

conditions.

At Waikiki, in

a response to calls for an improvements to beach safety,

The Outrigger Club announced its members would man a patrol

during the tourist season.

Duke Kahanamoku

and Vincent Genoves, accompanied by Lew G. Henderson and "Dude"

Miller departed Honolulu on the 7th February to compete in the

U.S. trials for the 1912 Olympic games.

At the dockside,

members of "the Hui Nalu gave their club yell, a

quintette club sang 'Aloha Oe,' Berger's band struck up 'Auld

Lang Syne.'"

The Hawaiian

Star printed a letter on 12th March from Dr. A. E.

Friesel to his brother, a local athlete, with an account of the

Olympic trials in Chicago.

He noted that

Genoves was severely disadvantaged by the short course tank

which required numerous turns, losing "one and one-half to

two yards on every turn," and failed to qualify.

The tank was less

of a problem for Duke Kahanamoku, in "the finals he won the

fifty yards and the 100 yards by about two feet each" and

he was selected for the U.S.A. team to swim in Stockholm.

Emphasising

Hawaii's status as a U.S. territory, "Duke was brought out

wrapped in the American flag."

Friesel requested

that his brother send him an autographed copy of "one

of those large photos showing him (Duke) standing on

his head on a surf board" to be framed for his office.

On the

mainland, Kahanamoku competed in a series of competitions and,

as of 22nd March, he had won every race he entered, with the

exception of one event at the Pittsburgh Athletic Club where he

retired from the race with cramps,

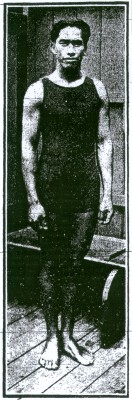

Described as 21

years old, six foot and 185 pounds, in particular, the press

noted "his style is different from anything ever seen before

in this country."

In interviews

Duke accredited his swimming success to his surf riding

experience at Waikiki.

Despite the years

of strenuous publicity by A.H. Ford to give the Outrigger Club

an international profile, its fame was now rivalled by "the

Hui Nalu ('Ocean Wave' Club) of Hawaii."

In mid May,

Waikiki experienced a large swell and "an unusually large

number of surf board riders were in evidence," while on

shore, a benefit dance was arranged by the Hui Nalu Club

to raise funds for Duke Kahanamoku's trip to the Olympic Games

in Stockholm.

Set for Saturday,

May 25, it was to be held at the Outrigger Club "and tickets

will be sold at 50 cents each."

After a complex

series of events and negotiations, Duke Kahanamoku won the 100

meters swimming finals at Stockholm on the 10th July, 1912.

After setting an Olympic record of 62 2-5

seconds in the heats (ratified after a protest from Germany),

Kahanamoku and the other American qualifiers, failed to appear for

their semi-final due to confusion about the schedule.

After meetings with the Olympic officials and the consent of the

qualified competitors from Australasia (a

combined team from Australia and New Zealand) and

Germany, a repercharge heat was run and two Americans, Duke and Kenneth Hustagh, advanced to the final.

Kahanamoku placed

first with Cecil Healy, representing Australasia, second;

Hustagh was third, followed by Germany's K. Bretting and W.

Ramme.

Australia's

champion, William Longworth, although qualifying for the

final, was too ill to compete.

The complications

in running the event were compounded by difficulties in

communication and it wasn't until six days later that the Honolulu

Star-Bulletin was able to announce Duke's victory

and world record.

Apart from an

outstanding athletic performance, Duke's "style" also made an

impression.

During the games,

James H. Randall, the San Francisco Call's

correspondent in Stockholm observed that he was " the talk

of the town today, not only for what he does, but for the

easy, nonchalant way in which he does it."

Furthermore, the

generous approval by the Australasian and German competitors to

a rescheduling of the semi-finals was highlighted by Dagens

Nyheter, the Olympic Games' special paper.

On 10th July, it

stated "the whole world of sport will ring with applause for

your sporting action in permitting the semi-flnal of the 100

metres to be re-swum."

Apart from Cecil

Healy's extensive career as a competitive swimmer he was also a

leading member of the Manly Surf Club, one of the four clubs

then operating on Manly Beach, Sydney's closest equivalent to

Waikiki.

Healy was, no

doubt, aware of the surfboarding exploits of Tommy Walker of the

neighbouring Seagulls Club and of Duke's surfing reputation..

As such, he had a

bond with Kahanamoku that was rare in Stockholm, and later was

one of the principal figures in issuing an invitation for Duke

to tour of Australia.

In the southern

summer of 1941-1915, he reported on the Kahanamoku tour as a

journalist for The Referee and was directly

involved in the Sydney surfboard riding exhibitions.

Following his

success at Stockholm, the Hawaiian Gazette

reported on the19th July that Duke Kahanamoku would tour Europe

and the United States, before a scheduled return to Hawaii on

the 23rd August.

Meanwhile,

preparations were under-way to honour him, "the gift

probably to take the form of a house and lot, in addition to a

purse."

It printed

selected excerpts from some of Duke's letters back home and

suggested that he would return via "Atlantic City where the

crowds will see him on the surf board."

Duke Kahanamoku

arrived in Atlantic City on 10th August, New York's The

Evening World reporting that "he brought

with him two of the surf riding boards used by the Hawaiians."

The boards were

forwarded from Honolulu directly to the East coast, possibly to

the care of George Macfarlane or the Henderson family, awaiting

his arrival.

The article also

noted that "the City Commisson forbids the use of boards in

the ocean, but has granted him permission to employ the surf

runners two hours a day."

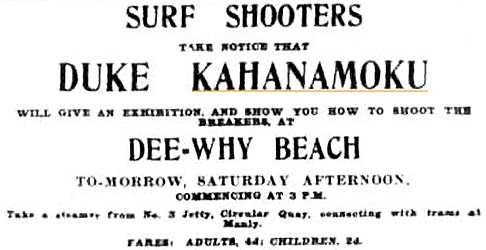

Atlantic City was

not the only civic authority to restrict surfboard use; in March

1912, the NSW Government enacted an ordinance giving local

inspectors power "to order bathers to refrain from

surf shooting, whether with or without a surfboard, where the

practice was likely to endanger or inconvenience other

bathers."

Both cases

indicate that these regulations were in response to the

activities of local surfboard enthusiasts.

Furthermore,

another report of Duke surfing at Atlantic City noted that his

board was "longer than the boards seen here."

Of course, this

was not the first appearance of Hawaiian surfboard riders on the

East coast.

Kahanamoku was

preceded by a group of surfing musicians, "the Hawaiian

quintette", who were booked to perform at Atlantic City

and Ashbury Park, N.J., in July 1910.

At Ashbury Park,

their board riding, "skimming on the crest of a wave for

hundreds of feet", was admired and copied by some locals,

with limited success.

Duke later wrote

to his father that he was "having a great time ... riding

the surf ... thousands of people were on the Million Dollar

Pier."

The New

York Herald of 16th August reported that his

appearances in Atlantic City had immediate impact.

It noted that "amateur

surf

riders here ... have provided themselves with surf boards,"

presumably larger designs than those previously used, and

"a new impetus has been given to surf riding and boys and

men may be seen at any hour of the day when the tide is just

right for the fun trying their skill striding in with the

waves."

His

upcoming itinerary included appearances at Ocean City, New

York, Philadelphia, and San Francisco.

Interviewed at

the end of September, following his return to Sydney from

the 1912 Olympic Games, the manager of the swimming team, Mr. A.

C. W. Hill, raised the prospect of a tour of Australia by "the

brilliant American sprint swimmer Duke Paoa Kahanamoku."

This was only one of the numerous invitations to

Duke following his Olympic success and the Australian tour would

not eventuate until the southern summer of 1914-1915.

Edward Rayment,

the director of the New South Wales Immigration and Tourist

Bureau, visited Hawaii in October 1912 on his way to London to

relieve Percy Hunter, who was to return to Sydney, via Honolulu,

"arriving here during February and remaining for carnival

week."

He was given the

standard tourist treatment including an "afternoon surfing

in canoes and watching the Hawaiian boys and Outrigger members

disporting themselves on the surfboards."

At the Outrigger

Club, Rayment met with Duke Kahanamoku and reiterated Hill's

invitation to visit to Australia.

Later that month

in Sydney, Hill reported to a meeting of the NSW Association

that he had approached several international champions in

Stockholm about their availability to tour Australia, and Duke

Kahanamoku was the most enthusiastic.

The association

resolved to apply to the Australian Swimming Union for power to

extend a formal invitation.

Although the

invitation was for a series of swimming exhibitions, "Merman,"

the natatorial correspondent for the Daily Telegraph,

commented:

"Should

Kahanamoku come to Sydney (he is claimed to be the world

champion surf-shooter in Honolulu), he will surely astonish

local surfers with his evolutions in the breakers."

Preparations were well under way in Honolulu in

December for the Mid-Winter Carnival, the program was to feature

"the Landing of Kamehameha the Great", accompanied by a

large fleet of canoes, at Waikiki.

He was to arrive

on a traditional double war-canoe, requiring Prince

Kalanianaole's canoe and one other to be brought from Kailua,

Hawaii.

At Waikiki, they

were to be "lashed together by a Hawaiian who did the same

for those in the Bishop Museum."

Other events

included surf riding and canoe races, in particular "Duke

Kahanamoku will be a star attraction la the surfing and

swimming performances."

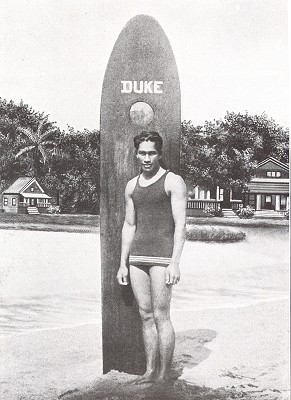

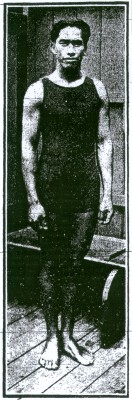

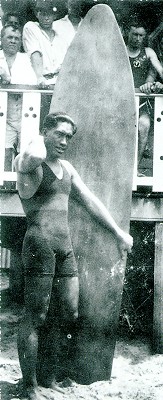

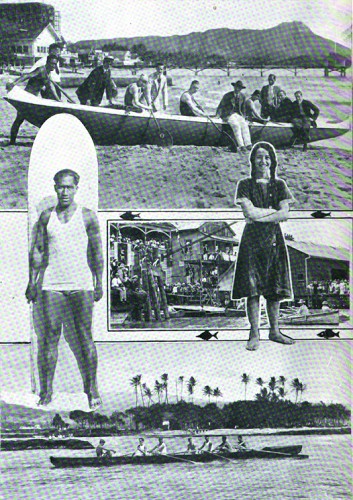

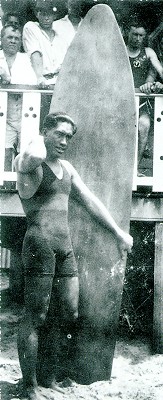

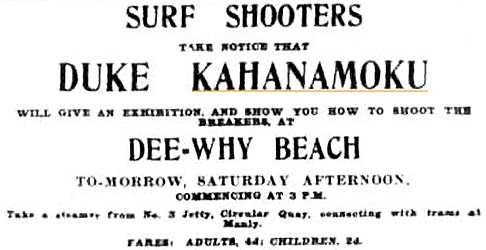

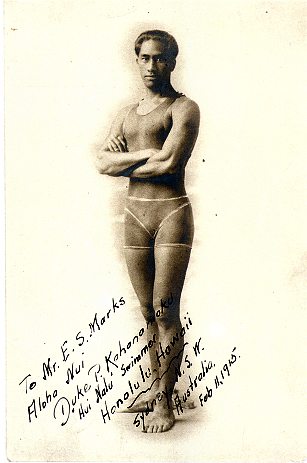

Circa 1912, Aloha

from

Hawaii, a publication produced to promote the developing

tourist industry, included an image (often reproduced) of

Duke and his board on the beach at Waikiki.

|

"DUKE"KAHANAMOKU

The

Hawaiian Swimmer

World

record holder 100 metres,

Time

1 min. 2 3/5 secs.

DUKE KAHANAMOKU -

The Champion Swimmer of the World.

Island Curio Co.: Aloha from

Honolulu.

The Island Curio Company, Honolulu,

T. H., circa 1912.

Note that

the nose template is standard for the majority of solid

timber boards of this period, and is in marked contrast

to the first board (the Freshwater board) he shaped in

Australia in 1914.

|

The

Daily Telegraph

30th October, 1912,

page ?

|

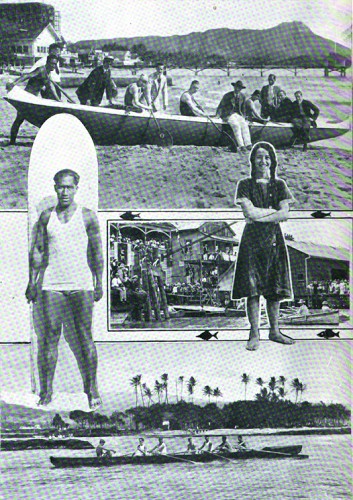

Subsequent editions of The Mid-Pacific

Magazine continued to feature articles and

photographs of surfboard and outrigger canoe surfing in Hawaii

(and other Pacific islands) with the December issue of

including a photograph of Duke surfing at Waikiki.

|

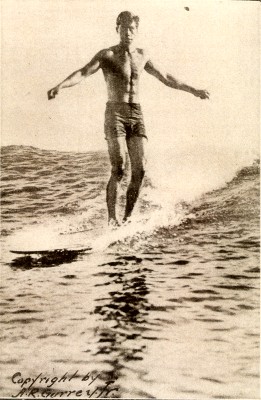

Duke Paoa

Kahanamoku,

Hawaii's Champion Swimmer of the World.

Copyright

by

A. R. Gurrey Jr.

The

Mid-Pacific Magazine

Published

by Alexander Hume Ford,

Honolulu,

Territory

of Hawaii,

Volume

4, Number 5,

December,1912,

unpaginated.

Note that

in this image Duke Kahanamoku is riding in "goofy"

stance (that is right foot forward), whereas subsequent

photographs indicate his stance as "natural" (left foot

forward).

Either

the image was flopped from the negative, or more likely,

he reversed his stance for the benefit of the

photographer.

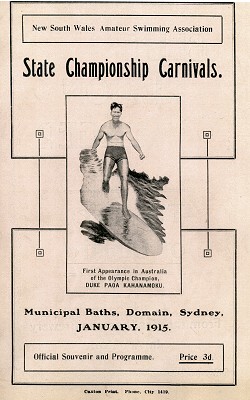

This

photograph, although in natural stance, was later

adapted as the template for an illustrated poster for

the Mid-Pacific Games of 1912.

This

poster was then appropriated by the NSW Amateur Swimming

Association to promote their series of swimming

carnivals in Sydney in 1915.

See below.

|

1913

On 29th January

1913, the Honolulu Star-Bulletin was quick to

pour scorn on a recent story in the opposition Advertiser,

later widely repeated, pro-ported to record "Duke

Kahanamoku's terrific battle with a high-powered, man-eating

eel."

Under the

sub-heading "Quick, Officer, the Padded Cell," the

HS-B reporter interviewed the Duke who confirmed

that there was a confrontation, that is "Duke was nipped by

a small eel when he stuck a finger into a crevice in the

coral."

The original

story was repeated in the Long Beach Press on 29

January, 1913.

The HS-B

also included an interview from the San Francisco Call

of the recent return from Hawaii of "the winner of the

Call's girl wage earner beauty contest," who included

Duke Kahanamoku amongst several gentlemen with whom she was

romantically linked.

At the beginning

of February The Salt Lake Tribune published an

extensive and flamboyant article on Duke Kahanamoku who "Made

the Fastest Swimmers of the World Look Foolish at the

Stockholm Olmypiad, Was Reared in the Surf of His Island Home

and as a Boy Dodged Sharks for Sport."

It was accredited

to Jim Nasium, "Copyright by The Philadelphia. Inquirer Co.",

and was reproduced in several other mainland papers.

Accompanied by

two photographs of Duke, there was also a dramatic surfboard

riding illustration, copied from the cover of John R. Mustek's Hawaii

- Our New Possesion, published in 1897.

Two weeks later

the Honolulu Star-Bulletin reproduced selections

from the Nasium article, identifying it as "a Sunday story

in the Philadelphia Enquirer," and made light of the

stories of shark dodging, the headline reading "Hold on

tight, This story makes Duke Kahanamoku's giant eel look like

a bait worm."

Towards the end

of May, at the request of a visiting team of Australian

cricketers, Duke Kahanamoku gave his first swimming

exhibition since his return to Honolulu.

Held off the

Moana Hotel pier, the event was a casual affair with no starters

or timers, Duke demonstrating his style and skill in company of

a number of locals.

Before starting,

he posed for more than half an hour at the request of tourists

and local photographers.

Afterwards Duke

took some of the visitors from "Kangarooland" into the

surf in one of three large canoes manned by the Hui Nalu, while

other club members gave exhibitions of surf riding.

The cricketers

expressed a desire to see the champion swimmer compete in

Australia, a prospect that was regularly canvassed in their

national press.

In Honolulu on

the 17th June, a morning paper (The Adveriser

?) reported that Duke Kahanamoku was considering an

offer to appear in vaudeville, reputedly at $1000 a week.

The claims were

emphatically rejected by Duke in the afternoon edition of the Honolulu

Star-Bulletin, and he made it clear that there was

no prospect of him turning professional.

He indicated that his prime focus was on the

upcoming swimming events in California, and the day before he had

collected "his special surfing

board" from Waikiki in anticipation of

riding it at Long Beach.

Duke also

expressed an ambition to surf on the beaches of Florida, but

noted few people visit the resorts there "in the baking hot

summer months and the big hotels are virtually closed until

late in the fall."

On the 18th June,

a team of seven Hawaiian swimmers, including Duke Kahanamoku,

left for San Francisco on the Wilhelmina to compete at

the Sutro Baths on the 4th July.

Led by William

T.Rawlins, their arrival was eagerly anticipated and there were

suggestions that further swimming events may be arranged in Los

Angles and surf riding at Long Beach, "where the breakers

usually are heavy and suitable for this kind of sport."

Before competing at the Los

Angeles Athletic Club on the evening of the 11th July, at

the

invitation of Pete Lenz, captain of the Long Beach high school

swimming team, the visiting Hui Nalu squad spent several hours

at Long Beach.

Here, "they

couldn't resist the surf and the Duke gave a thrilling

exhibition of surfboard riding" before a crowd of

"thousands."

After the day's

surfing, Kahanamoku easily won his swimming events that night.

Manager Rawlins

and the majority of the Hui Nalu team; H. W. D. King, Lukelai

Kaupiko, D. Keaweamahi, H. Kahele, C. W. Hustace, Frederick

Wilhelmn and J. B. Lightfoot; returned to Honolulu from

California aboard the Sierra on the 21st July.

Duke Kahanamoku

was to return "in about a week" and Robert Kaawa was

reported to have "yielded to the lure of the footlights and

will go into vaudeville."

Rawlins detailed

Duke Kahanamoku's success in California to the local press.

Apart from his

expected victories, he won the the fifty-yard breast-stroke "

though he has never practiced that style" and in a race

against California's Ludy Langer over three-quarters of a mile,

despite not contesting the distance before, he bested Langer's

record by two and a half minutes.

During the tour,

Curtis Hustace and Duke gave a surfriding exhibition at Venice

where "Hustace came in on the surf -board standing on his

head about twenty times, and twenty thousand people went

wild."

The San

Francisco Call advertised Duke Kahanamoku's final

mainland appearances would be at the Casino Natatorium, Santa

Cruz, on the 26th and 27th July .

The event was

said to include "all the crack swimmers and divers of the

coast, in races, high and fancy diving, surf riding."

The Maui

News of the 9th August reported another invitation

for Duke Kahanamoku to tour Australia with an offer "to pay

the expenses of Duke, his manager and trainer."

It was suggested

that a tour could start with within a month.

Furthermore, the

article commented on the swimming skills of the Solomon

Islanders, "where the great Wickman came from,"

particularly the women, of whom it was said "would

swim circles around anything Honolulu has so far produced."

Crucially,

demonstrating the dispersion of the "crawl" style across the

Pacific, they noted "the famous Duke kick is native, not to

say indiginous (sic), to that section of the world and

the women all use it."

The "great

Wickam" was Alick Wickham, originally from the British

Solomon islands, who was a leading competitor in the Sydney

swimming fraternity and was often accredited with developing the

"Australian Crawl" with the Cavill family in the late 1890s.

In 1949, Wickham

was accredited by C.B. Maxwell with shaping the first surfboard

in Australia around the turn of the century.

She noted that

the board was not a success- it was hand carved from a piece of

driftwood found on Curl Curl beach and sank.

During 1903 he

set a world record for 50 yards and equalled the Australian

record for 100 yards at Farmer's Rushcutter Bay Baths, Sydney.

In 1905 Wickham

led the "Manly Ducks", a team that "performed

exhibitions of fancy diving and swimming," the other

members were A. Rosenthall, L. Murray, H. Baker, and C. Smith.

Harold Baker

later identified Wickham, along with "(Cecil) Healy,

the Martins, Colquhoun-Thompson, Read, F. C. ('Freddie') Williams,

and (Charlie) Bell", as one of "our best

(surf) shooters" (bodysurfers).

Healy and Wickham

were both members of the Manly Surf Club, and Wickham was one of

Cecil Healy's strongest competitors in the lead up to his

selection to the Australasian team for the 1912 Olympic Games.

In 1918, Wickham,

then aged 33 and appearing under the name "Prince Wickyama,"

set a the still-standing world's record by diving from

a height of 205ft 9in. into the Yarra River at Deep Rock Baths,

Melbourne.

The feat was

nearly fatal, and Wickham was hospitalised for several days.

Wickham was not

the first, or the last, Pacific islander to have a significant

influence on Australian swimming and surf-riding.

Body-surfing was

introduced at Sydneys' Manly Beach in the 1890s by Tommy Tana, a

native of the island of Tana in Vanuatu (then the New Hebrides).

His style was

studied and copied by Manly swimmers, notably Eric Moore, Arthur

Lowe and Freddie Williams, who was considered to be the first

local to master the sport.

On the 18th

September, Mr. W. W. Hill, the Australian Swimming Union

secretary, announced that Duke Kahanamoku would visit Australia

to compete in Sydney and Brisbane at the 1913-1914 national

championships

W. T. Rawlins,

president of the Hui Nalu Club, had recently written to Hill

confirming Duke's enthusiasm to tour and noted that on the

recent San Francisco trip "he broke many records, among them

the 100yds record held by your Wickham."

Rawlins wrote

that, following another visit to California in October, "we

will start for Sydney the first week in November."

This tour was

formally cancelled in a cable to the the A.S.U. on the 4th

December.

Mr. W. W. Hill,

in his role as secretary of the New South Wales Rugby Union, was

invited to referee several games in California during October

1913.

These included an

annual match between the University of California and Stanford

University, and matches played by the touring New Zealand "All

Blacks" against the All-American team and California

University.

Returning via

Honolulu in December, he contacted Duke Kahanamoku "in

regard to a visit to Australia," however, Duke was

currently unavailable due to "private business" commitments.

While at Waikiki,

Hill "mastered the art of surf-board riding, and canoeing in

front of the wave."

Hill noted that "the

Hawaiian Athletic Union wants to send a team to Australia next

season."

On the last day

of the year, the Sydney Morning Herald published

an extensive article on Waikiki and Duke Kahanamoku, apparently

based on a recent interview by a visiting Australian, perhaps

W.W. Hill.

It detailed the

Waikiki beach-front, the surfing conditions, and board and canoe

riding, followed by a brief description and biography of Duke

with a list of his five current world records.

While he was

always willing to demonstrate his swimming technique, "when

asked how he 'kicked,' Duke was quite at a loss to explain;

and he finally gave it up, and said he did not know, but just

kept going naturally."

Informed of the

nature of the harbour pools in Sydney, Kahanamoku "was

surprised to hear of the enclosed baths, as, like all

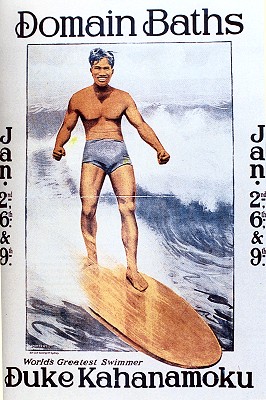

the natives, he has no fear of sharks."

Indicating that

an Australian tour was confirmed for the next December (1914),

the journalist suggested that the climate, the water

temperature, and the 100 metres straight-away course of the

Domain baths would see Duke swim times "even faster in

Sydney than he has done hitherto."

1914

In January, the

Hui Nalu Club, "of which Duke Kahanamoku, world's champion,

is a member," announced plans for a clubhouse at Waikiki.

As a fund-raiser,

the club membership was preparing for two performances of "The

Hui Nalu Follies," to be presented at the Honolulu

Opera House.

The Follies were

held on the 12th and 13th February and the press reported

that it was crowd had "an evening of riotous fun,"

with one of the most popular numbers being a dance by Duke

Kahanamoku partnered by Ned Steel, "dressed like an

up-to-date chorus lady."

At a swimming

carnival at Honolulu at the end of February, Duke won all his

events except for the 50-yard -race, where he was unexpectedly

defeated by Bob Small, of California.

However, Kahanamoku's main rival on the day was

George Cunha of the Healani team, who would later accompany Duke

on the Australian tour.

Around this time, Reg "Snowy" Baker, who

competed across range of sports including swimming and was later a

sports promoter, wrote from Honolulu that he "had the pleasure

of a long yarn with the world's champion swimmer, Duke

Kahanamoku."

He commented on Duke's athleticism, pleasant demeanour, swimming

technique, an enthusiasm for motor-bikes, and his anticipation of

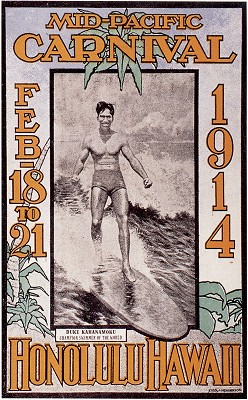

the visit "our great country."

Baker also noted that the carnival there was promoted by

"life-like pictures of Kahanamoku shooting on a surf board;" the

same poster would be reproduced for the Sydney carnivals.

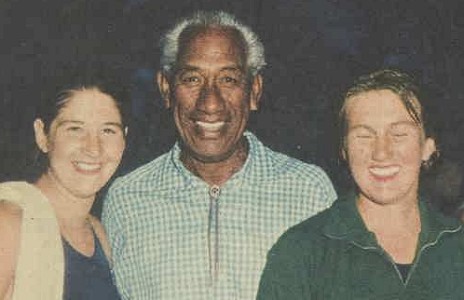

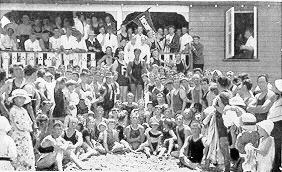

|

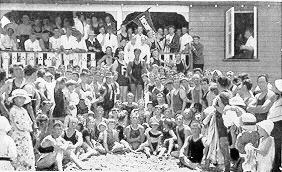

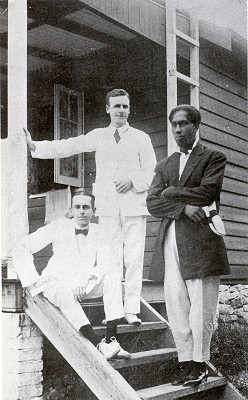

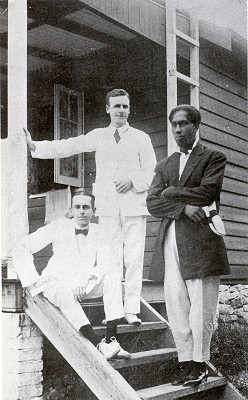

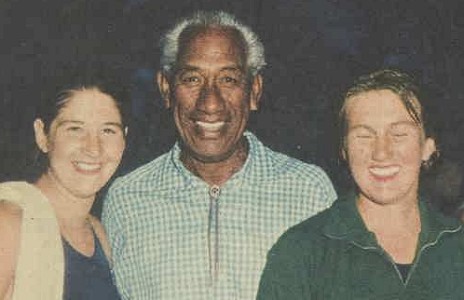

Monday

14th December 1914: Arrival in Sydney.

Duke

Kahanamoku , accompanied by 19 year old surfer/swimmer

George Cunha and manager Francis Evans, arrived in Sydney

on RMS Ventura.

Despite a delay due to rough seas outside the Heads, a

large number of officials, press and public were at the

wharf when the steamer docked after a two week voyage from

Honolulu.

The officials included E.S. Marks and W.W. Hill, who as

the secretary of the Australian Swimming Union and had met

with Duke twelve months earlier in Honolulu to advance

preparations for the tour.

Sydney's premier athletic track is named after former Lord

Mayor of Sydney, E.S. Marks who won over forty trophies as

an athlete between 1888 and 1890. He was a founding member

of the North and East Sydney Amateur Swimming clubs, Manly

Surf Club; and the New South Wales Amateur Swimming

Association, and a touring manager for the Australian team

at the 1912 Olympics.

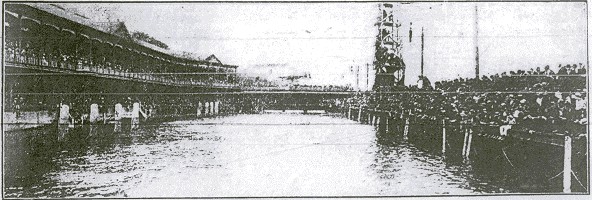

DUKE KAHANAMOKU

The fastest swimmer in the

world, photographed

at

the Sydney Domain Baths two

hours after his arrival in Sydney.

GEORGE CUNHA, SECOND ONLY TO

KAHANAMOKU AS SWIMMER IN HAWAII.

He secured second place in most

of the Pacific Coast Championships, and can do

100yds in 57sec.

He is one of the Honolulu party

now in Sydney.

Photographs: The Referee, 16

December 1914, page 11.

|

|

After the touring party travelled to their

accommodation at the Oxford Hotel, they inspected facilities at

the Domain Pool and then attended an official reception at the

Hotel Australia.

Cecil Healy, now a journalist for the Referee, Sydney’s

premier sporting publication, missed the ship’s arrival but

attended the evening reception.

At the Stockholm Olympics in 1912, Healy had placed second

to Duke in the 100 metres sprint.

Tuesday

15th December 1914: Tour schedule to include

surf-riding?

The Sydney Morning Herald detailed Duke’s

tour schedule, beginning with a series of swimming

carnivals at The Domain Pool in Sydney on 2nd, 6th and 9th

January and followed by carnivals in several towns in

Queensland.

On returning to Sydney “the Swimming Union will probably

in arrange for a surf display, when the champion will be

seen on the surf-board.

Matters in this direction have not yet been finally

arranged."

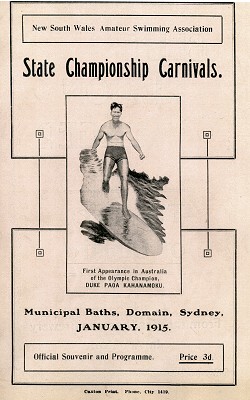

The Swimming Union contributed to growing expectations for

a surf display by promoting the swimming events with a

dramatic illustration of Duke surfing at Waikiki.

Copied from the previous year's poster for the Mid-Pacific

Carnival, an illustration base on a 1911 photograph by

A.R. Guery, it also graced the official

program's cover.

Mid-Pacific Carnival

Kampion:

Stoked (1997) page

38, credited to Bishop Museum.

|

|

|

Wednesday 16th December 1914:

Coogee Carnival, Surfboard Ban? A Board to be Shaped?

Duke Kahanamoku attended the annual Randwick versus Coogee Club

carnival at the Coogee Aquarium Baths.

The competitors included Cecil Healy, A. W. Barry, L. Boardman, T.

Adrian, and W. Longworth and “Miss Fanny Durack gave

an exhibition swim of 200 yards.”

Fanny Durack was another competitor at the Stockholm in 1912, the

first Australian woman to win an Olympic gold medal in a swimming

event.

In the press, the front page of The Referee featured

Cecil Healy’s report of Duke’s arrival and the “magnificent

reception (where he) managed to get a chance to shake hands and

have a chat with him.”

Of course, the outbreak of the war in Europe, with the first

contingent of ANZAC troops already embarked, tended to overshadow

the celebrations.

One of the speakers, H. Y. Braddon, noted that while there ”seemed

to a desire to put off carnivals and similar events, owing to the

war, ... it was a good thing to hold them, as they meant work for

someone.”

Healy questioned Duke on his visit to the Domain Pool (“just fine,

and the water's great") and asked:

" ‘Did you bring your surf board with you?'’, to which he replied:

'Why no, we were told the use of boards was not permitted in

Australia.'

Evidently noticing the look of keen disappointment on my face, he

quickly added 'But I can easily make one here'.

This information, I am sure, both swimmers and surfers will be

delighted to be acquainted with, as holding out prospects of the

acquirement of the knack of manipulating them."

The supposed ban on surfboards in Sydney was reported by American

journalist and enthusiastic (self) promoter, Alexander Hume Ford,

a principal character, along with George Freeth, in Jack London's

celebrated account of surf riding at Waikiki, A Royal Sport,

in 1907.

Following a visit to Australia in the summer of 1907-1908, Ford

published an article in The Red Funnel, an early

tourist magazine, where he claimed that at Manly Beach he “wanted

to try riding the waves on a surf-board, but it was forbidden.”

While surfboard use had been regulated for the safety of

body-surfers on Sydney’s beaches since March 1912, it was not

prohibited.

On returning to Honolulu in 1908, Ford was integral in the

founding of the famous Outrigger Canoe Club at Waikiki on prime of

beach front property, an idea possibly influenced by observing the

beginnings of the first surf life saving clubs while in Sydney.

Thursday 17th December 1914: Competition,

Beaches, and the Needs of a Waikiki Beachboy.

By the end of the week, the arrival of Duke Kahanamoku in Sydney

had been noted by newspapers from Townsville to Perth, including

The Farmer and Settler, The Australian Worker, and The Catholic

Press.

While Duke had few official engagements in the weeks leading up to

his first swimming carnival scheduled for 2nd January, there were

a number of important developments.

Firstly, Francis Evans and NSW Swimming officials were busy

conducting negotiations for Duke‘s appearance at a number of

carnivals in Melbourne.

Whereas the Victorian Association had previously declined

involvement in the tour, with the wide-spread publicity, it was

now seriously reconsidering its position.

Secondly, given the results, it is likely that Duke and George

Cunha did some training to prepare for the swimming competitions.

However, any sessions were probably in the early morning, to avoid

onlookers, and could have been at any one of a number of suitable

local pools.

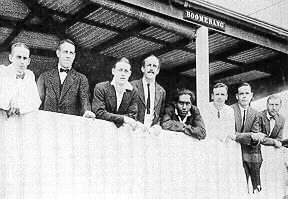

Also, at some point Duke crossed the harbour, presumably on one of

the ferries of the Manly and Port Jackson Company, and became

acquainted with the beaches of Sydney’s north shore, in particular

Freshwater and the Boomerang camp.

Most importantly, Duke was without a surfboard, a ukulele and some

poi.

Friday 17th - Tuesday 21st December 1914:

Duke’s Freshwater Board

Duke shaped his famous Freshwater board during the first week of

his arrival in Sydney, at some time between 17th and 21st

December.

In many contemporary articles the width and length are often

reported incorrectly, and errors appear in many subsequent

accounts.

For example, Nat Young (1979-2003) records the length as 3.6 m (or

11 ft 10’’). Also note that some have asserted that Duke shaped a

concave section in the bottom, a feature that is not, however,

evident.

The actual dimensions are 8 foot 6.5 inches long, 23 inches wide

and 2.75 inches thick, with a weight of 78 pounds.

All reports indicate the timber as sugar pine (Pinus

lambertiana), a substitute for the significantly lighter

Californian redwood as “a properly seasoned piece of that

particular timber, sufficiently long, could not be procured in

Sydney,” at short notice.

As a result the board was considerably heavier than normal, which

Duke suggested was a disadvantage as his Waikiki board “as a rule

weighs less than 25lb.”

The weight was not the only distinctive feature, the nose template

is unusual and it was not replicated on the boards shaped in

Australia following Duke’s departure.

The template was probably not cut by Duke, Reg Harris (1961)

suggesting that the billet was donated by a timber firm, George

Hudson’s, who “did the rough cutting to Duke’s instructions then

he finished off the finer designing of the bottom of the board.”

Although Hudson's apparently had several timber yards in Sydney,

the principle premises were at Blackwattle Bay, Glebe, and it is

the most likely source of the billet and the initial cutting of

the template by an experienced tradesman.

In the haste to produce a board, the template may not have been

cut exactly to Duke’s instructions.

However, whatever its deficiencies, the board’s status is assured

as Duke generously accepted it in the spirit of aloha and was

happy to use it, apparently, at all his surf riding exhibitions in

Sydney.

Either at Hudson’s or, more likely, after the board was

transported across the harbour, Duke rough-shaped the bottom and

rails with the tools at hand, ideally a small adze and a draw

knife.

He then would have finished it with various grades of sandpaper

and sealed the board with a coat of a natural oil or marine

varnish.

Although by this time a number of surfboards had been built in

Sydney, notably by Les Hinds of North Steyne, this was the first

by a professional shaper.

Given his impeccable credentials, any who witnessed the craftsman

at work were accorded a rare honour.

The board was finished, and even perhaps test ridden at

Freshwater, by the 21st December 1914.

This is simply based on the assumption that whoever placed an

advertisement with the Sydney Morning Herald on

that day did so only with the certain knowledge that the board,

and rider, were ready.

The next morning the Herald announced:

“The New South Wales Swimming Association has arranged for a

display by Duke Paoa Kahanamoku at Freshwater on Wednesday

morning, at 11 o'clock.

The famous swimmer will give an exhibition of breaker shooting and

board shooting.“

Acknowledgement

My sincere thanks Eric Middledorp, the board's custodian at the

Freshwater SLSC, for his dedication and invaluable assistance.

Eric has overseen the recent excellent restoration and enhanced

presentation of Duke’s board, in addition to supervising the

shaping of an active replica.

Saturday 19th December 1914: The Sydney vs.

Melbourne Carnival

Duke, probably accompanied by George Cunha and Francis Evans,

attended his second Australian carnival at the Domain Pool on

Saturday 19th as a spectator.

His attendance at the carnival does not eliminate this day for the

shaping of the Freshwater board, but makes it very unlikely.

The carnival was the annual swimming competition between the

“crack” swimmers from Sydney and Melbourne, with the honours going

to Sydney on this occasion.

On show were Boardman, A. W. Barry, and Tommy Adrian from

Sydney, all potential Duke rivals.

The performance of Ivan Stedman from Melbourne was impressive and

he was seeded into the heats for the first Kahanamoku carnival on

the 2nd January 1915.

This further increased the interest of Victorians in the tour, and

gave Francis Evans and the NSW Association additional leverage in

the negotiations with Melbourne’s swimming officials, now keen to

secure dates for Duke’s appearance in their city.

The word “carnival’ was very apt, swimming races were only the

central feature of a program that regularly included diving

competitions and displays, novelty events, and, occasionally,

musical entertainment.

In the springboard diving at this carnival, Barry was second to

Melbourne’s L. Grieve.

Very popular with the public, the carnivals were a significant

source of income for the amateur Associations, and in this

instance, the cost of the Kahanamoku tour was to be covered by the

gate receipts.

The cost was considerable: steamship from and return, via New

Zealand, to Honolulu, two months first-class hotel accommodation,

transport and all incidentals, for three.

In making the bookings the negotiations could be protracted, the

managers seeking suitable discounts or extras in respect of the

fame of their client, or quickly and amicably arranged by swimming

or surfing enthusiasts or through an “old-boy-network.”

The expenditure incurred by the NSW Swimming Association, or the

income generated by the Kahanamoku tour has never been, even

vaguely, estimated.

In this era, swimming races could be chaotic, with large numbers

of swimmers and often with cases of interference.

Concerned that such problems may detract from the importance of

the upcoming Kahanamoku carnivals, in a letter to the Sydney

Morning Herald, “Swimmer” proposed a novel solution:

“A new scheme might also be tried by roping the course as in foot

running, where each competitor has his own track.”

Sunday 20 December 1914: Not Manly (but

Freshwater?) and the ukulele.

During the first week in Sydney, Duke shaped his board and visited

north of the harbour, in particular, Boomerang, one of several

basic shacks built on the frontal sand dune at Freshwater Beach

shortly after the turn of the century.

It was now owned by Donald McIntyre, a founding member Freshwater

Life Saving Club, who had served as club secretary, and now held

that office for the New South Wales Surf Bathing Association

Given his appearances at carnivals and social events, Duke’s

visits may have been short, but as with the construction of the

board, there was certainly at least one fleeting visit between the

17th and 21st December 1914.

As discussed above, the Sydney Morning Herald announcement

of the 22nd could only have been made once the board was finished

and Duke had tested the waves at Freshwater, with or without the

board, but probably both.

The most likely scenario is one visit to shape, varnish and body

surf, with a return a couple of days later to test-ride the board.

While Freshwater was a surfboard riding beach, it was clearly

second to Manly.

As clearly stated in the official 1910-1911 NSW Surf Bather's

Guide, Manly is “the original home of the surf bather.”

Whereas Freshwater had one surf life saving club, by 1914

Manly had four.

Most had some connections back to the harbour side Manly Swimming

Club, formed in 1905, whose objectives included “proficiency in

life-saving on the Ocean Beach.”

The first club on the beach-front was the the Manly Surf Club,

with its star Olympic swimmer, current journalist and soon-to-be

Duke competitor, Cecil Healy.

This was followed by North Steyne Life Saving Club, with surfboard

shaper, Les Hinds, and C. D. Paterson, serving as president of

both North Steyne and the Surf Bathing Association of New South

Wales.

Claims that Paterson brought, or procured, or was gifted, a

full-size surfboard from Hawaii, sometime between 1908 and 1912,

have never been substantiated.

Several accounts note that the board was unable to be mastered by

the locals; which, in light of other evidence, appears highly

unlikely; and was then retired to the family home as an ironing

board, which appears to be a fable.

Next was the Manly Life Saving Club with Fred Notting, a pioneer

of canoe surfing, which was later to influence, and be eclipsed

by, Harry McLaren’s surf-ski, first tested in the surf at Port

Macquarie in the mid-1920s.

The most recent club was the South Steyne Life Saving Club, with

W. H. Walker as the honourable secretary, a position he had held

in the now defunct Manly Seagull Surf and Life Saving Club, who

had their “membership restricted to residents of Manly.”

The Seagulls had started at the same time as Manly LSC, both

recruiting disaffected members from Manly Surf, which refused to

register with the newly formed state body.

Besides W. H., the Walkers (some of the connections are unclear)

were a prominent force in the surf along Manly Beach.

As well as George and Monty Walker, of Manly, there was Tommy

Walker of the Seagulls and Yamba.

Tommy did travel to Waikiki, did buy a surfboard there, did bring

it back to Australia, and by 1912 was able to ride it upright like

the Hawaiians, both on his feet and on his head.

In early 1912, Tommy Walker, on his “Hawaiian surfboard” and Fred

Notting, “in his frail canoe, The Big Risk" gave demonstrations at

carnivals at Freshwater and Manly.

They repeated these the following summer, however, this time Fred

was “accompanied his dog, Stinker.” In the early 1920's, Russell

Henry 'Busty' Walker, following Fred Notting, was invaluable as a

judge at the buoys at Manly Surf Carnivals and around the same

time, W, H. Walker’s son, Ainslie "Sprint" Walker, introduced

board riding to Torquay.

Tommy Walker was an inspiration to other locals and in early 1913,

while enacting another ineffective ban, one Manly Councillor

claimed to have “seen no fewer than 10 surfboards in the thick of

bathers,” but “Dumper, an old hand on the board,” later suggested

this was a considerable exaggeration.

The next summer records the first surfboard injury in Australia,

not surprisingly at Tommy Walker’s, second home, Yamba, and later

the same year Harald Baker crowned “young Walker the surf

board king."

With board riding “a practice at Manly for some years past ...

Young McCracken is (Tommy Walker’s) closest rival,” followed by G.

H. Wyld of Manly and “Champion Sprinter Albert Barry.” In the new

year both Wyld and Barry were to compete against Duke in the pool.

Baker, an outstanding swimmer and a captain of the Maroubra Surf

Club, considered “Miss (Isma) Amor is the best lady exponent so

far,” a view supported by other accounts.

As well as Manly and Freshwater, by the winter of 1914, surfboards

were known to be in use at Coogee, Maroubra and Cronulla.

With the status of Manly as Surfboard-City, why did Duke go

to Freshwater?

Donald McIntyre accommodated Duke in a shack at Freshwater, while

he could have, more comfortably, done so at his family home, of

the same name, in Manly.

And if not the McIntyre residence, there were undoubtedly several

other families in the village who would have warmly welcomed their

visitor.

In the lead-up to the tour, Manly’s Cecil Healy was an

enthusiastic champion of Duke, devoting considerable column space

to his achievements in the pool and strongly encouraged the

staging of surf-riding exhibitions.

At the end of November, three weeks before Duke’s arrival, Healy

wrote that the North Steyne Surf Club had initiated negotiations

with the NSW Swimming Association for Duke to “give a display of

surf-board shooting at its carnival, to take place about the

middle of December.”

A precedent was set, and a brisk exchange of opinions and options

between managers and officials would play out over the following

weeks.

By the 21st Duke had his surfboard and by the 19th he had a

ukulele, just in time to perform several numbers, with Cunha and

Evans, at the dinner party following the Sydney-Melbourne

Carnival.

“The three visitors were delighted when the instrument was

produced ... procured in Sydney through the courtesy of George

Walker, Manly.”

This was not the first exchange of important gifts between the

Walkers and Duke Kahanamoku.

In notes prepared for, but not used by, C. Bede Maxwell in her Australians

Against the Sea (1949), the talented Palm Beach board rider

and the president of the Surf Life Saving Association of Australia

from 1933 to 1974, Adrian Curlewis, recalled that Duke’s

Freshwater board was handed over to George and Monty Walker of

Manly.

Later, “because of the fine work Claude West had done in

popularising surfboard riding, (they) eventually gave it to Claude

West, and he still has it, a prized possession.”

At the end of the1930s, Harry McLaren’s surf ski made its first

excursion outside Australia when “the Walker Brothers sent a surf

ski to Duke Kahanamoku at Honolulu and members of the Australian

Pacific Games Team which visited Honolulu in 1939 say Duke was

often seen paddling around on his ‘ski from Australia’.”

Brief footage from around this time of Duke riding the ski at

Waikiki, while standing with two women passengers and a beach-boy

steering at the tail, is remarkable.

Monday 21st December 1914: A tour

of the South Coast, meanwhile, Freshwater contacts the SMH.

The highlight of the day for the Kahanamoku party was intended to

be a motor-tour of the South Coast.

However, while they were in transit, a brief conversation with Sydney

Morning Herald by someone from the Freshwater club

would prove to have significant ramifications.

This would suggest that the board was already completed at least

the day before, Sunday 20th.

The touring party consisted of Duke, George Cunha and Francis

Evans with representatives of the Association and friends

including swimmers Freddie Williams, Jack Longworth, Redmond

Barry, and Miss Fanny Durack.

The “South Coast” was probably the road from Stanwell Park,

possibly going as far as Bulli and the cars were provided “by

Messrs. Phiffer, M’Lachlan, Sam Smith, and F. Stroud.”

The day served as trial-run for Mr. Stroud of the Cronulla Club,

some members of which were known to have experimented with

surfboards.

Stroud was one of the drivers who transported the Hawaiian

swimmers from Sutherland station to Audley on 7th February, before

they proceeded to Cronulla by ferry for their last appearance in

the Australian surf.

While Manly had a long history as a tourist attraction, ideally by

the ferry from Circular Quay, the northern beaches were slower to

develop. Just far enough away from Manly to avoid the scrutiny of

the officials who were charged with enforcing bathing

restrictions, Freshwater’s other attractions were cheap

real-estate, protection from the prevalent summer Nor-Easter, and

an escape from the “suburbanites.” (For east coast surfers, this

often indicates residents of any suburb located to the west of

their own; invert this for west coast surfers).

Fred Notting, in an early example of “surf rage,” recalled the

days of his youth:

"We used to abuse the living daylights out of those we brought in

(rescued).

Put them off coming back to 'Freshie' pretty often. Suited us!"

Freshwater demonstrated its support for surfboard riding as early

as 1911, the club secretary, W. R. Waddington, wrote to the local

council to protest against the imposition of a ban and applied

“for authority to regulate the use of surf boards on Freshwater

Beach.”

Although a ban “would deprive many of the members and visitors of

the full enjoyment of the exhilarating surf,” the council

“unanimously agreed not to permit the use of the boards at

Freshwater.”

As in many cases of prohibition, the ban was impossible to

rigorously enforce, and complaints about surfboards to the press

and the passing of council motions continued.

Boomerang, was owned by Donald McIntyre, a founding member

Freshwater Life Saving Club, who had served as club secretary, and

now held that office for the New South Wales Surf Bathing

Association.

Recall that the current president of that body was C. D. Paterson,

who was also president of North Steyne.

For Duke, staying at Boomerang provided relatively secluded access

to the sea to become familiar with Australian conditions.

It was probably also a respite from the consistent attention of

fans and the press.

The rudimentary facilities of the shack may have replicated his

early days at Waikiki, but, this may, or may not, have been an

attraction.

Over the past two years Duke had visited the largest cities of

North America and Europe, and, in comparison, the facilities on

the tour of Australia were probably fairly average.

New Zealand was still to come.

As North Steyne had already made an approach about hosting a

surfboard riding exhibition by Duke well before his arrival, the

prospect such an event was likely to be raised with some of the

other Sydney clubs.

Of course any appearance would have to be with the consent of the

Swimming Association and at a suitable time in the schedule.

Don McIntye, distinctive in a white suit, is prominent in many of

the photographs, indicative of his central role in organising the

exhibitions and over-seeing Duke’s needs at Freshwater. These

duties may have included contacting the Sydney Morning

Herald on this day with the details of an exhibition

by Duke to be held in two days time.

However, regardless of who made the call, the situation was only

made possible courtesy of W. H. Hill, undoubtedly the prime

conduit in securing Duke’s appearance at Freshwater.

As the secretary of the Australian Swimming Association, Hill was

privy to all the plans and deals in organising the tour, beginning

twelve months earlier when he meet with Duke, and negotiated and

his management, in Honolulu.

Secondly, he was a founding member of the Freshwater club, serving

as the “starter” at the inaugural carnival in 1909, and familiar

with the aims and available resources of the club. Aware that an

exhibition on one of Sydney’s beaches was a realistic possibility,

Hill was keen to secure the event for his club, and the prospect

of shading their rivals over the hill, North Steyne, was a further

encouragement.

If any more incentive were necessary, the fact that North Steyne

was the club of C. D. Paterson, Hill’s president at the NSW Surf

Bathers Association, possibly added a personal element. W. W. Hill

had recognised that the club which first presented Duke in

Australia would achieve incontestable prominence in surfboard

riding, a view that has proved to be remarkably accurate.

Within the first days of Duke being in the country, Freshwater a

club had probably already made an arrangement directly with

Francis Evans, possibly at his suggestion, in the belief that this

would be independent of any contract with the Swimming

Association.

However, as it was likely that the date of the surfing exhibition

was initially unspecified; as it would, at the least, depend on

procuring a suitable board; the speed in which the first

exhibition was arranged may have surprised Hill, along with

many others.

The Hawaiian managers were familiar with such difficulties, and

the income generated by Duke’s surfing, initially surfboard

shaping but also exhibitions, was a consistent threat to his

amateur status as an Olympic swimmer in the eyes of US

authorities.

In 1922, his endorsement for Velspar marine varnish raised the

amateur issue once more some for American administrators.

As noted above, any appearance by Duke would require the consent

of the NSW Swimming Association and at a suitable time in the

schedule, and the will of the board would prevail, although they

also recognised the need to negotiate a suitable compromise.

Tuesday 22nd December: Surfboard Exhibitions Announced.

This morning the Sydney Morning Herald announced :

“The New South Wales Swimming Association has arranged for a

display by Duke Paoa Kahanamoku at Freshwater on Wednesday

morning, at 11 o'clock.

The famous swimmer will give an exhibition of breaker shooting and

board shooting."

As discussed above, this information could only have been passed

to the Herald for publication on the previous day (Monday, 21st)

and once Duke had shaped his board and assessed the Freshwater

surf as suitable.

The notice undoubtedly originated from Don McIntyre, secretary of

the Freshwater L.S.C., however a proxy may have made the contact

with the Herald.

At the Freshwater club on Tuesday morning, in eager anticipation,

the members would have been busy preparing for the next day’s

events, with realistic expectations of a considerable crowd.

However, when the officials of the NSW Swimming Association became

aware of the event, there was consternation. In their view, the

announcement clearly contravened their contract with Duke,

specifying his first public appearance in Sydney as 2nd January.

While the managers and officials were under considerable pressure,

the swimmers were probably largely shielded from most of the

contractual intricacies, and Duke could have been relatively

relaxed.

In respect of the upcoming exhibition, by now he had several years

of experience in appearing before the public, both at swimming and

board riding events.

On the surfboard he had competed and given exhibitions many times

in Hawaii and had demonstrated his skills on both coasts of the

United States.

While the waves of Freshwater were definitely different from those

of Waikiki, Duke had undoubtedly encountered similar conditions,

perhaps worse, at some of the beaches of North America.

Of all the officials, it is to be expected that the pressure on W.

H. Hill was extreme.

While he was likely the initial contact between Duke’s management

and the Freshwater club, as secretary of the Swimming Association

he was now required to protect, and enforce if necessary, the

terms covering their considerable investment.

The accusations, condemnations, and negotiations continued all

day, and only on the following morning was the difficulty finally

resolved. To his credit, Hill probably had a major role in

negotiating the alternative proposal that was accepted, if

somewhat reluctantly, by all the interested parties.

That is, except a hugely disappointed public.

It appears that Duke Kahanamoku did not meet with Australia’s best

board rider, Tommy Walker, in the summer of 1914-1915, as he had

probably steamed north to work at Yamba before Duke arrived in the

country.

In a remarkable case of coincidence, on the very day the Duke

notice was published in the Sydney Morning Herald , the Clarence

and Richmond Examiner reported that the program for the Yamba Surf

Life-saving Brigade Carnival, scheduled for New Year's Day, was to

include:

“An exhibition of shooting the breakers with the aid of a board is

to be given by Mr. T. Walker, who has had considerable experience

on other well-known beaches.”

Fortunately for the Yamba club, the announcement of Tommy’s Yamba

exhibition did not embroil it in a series of complex machinations

between managers and officials, such as was now taking place in

Sydney.

Wednesday 23nd December: The Exhibition that

Wasn’t.

Having read or heard of the Herald’s announcement published

yesterday, the vast majority of the spectators making their way to

Freshwater on this morning were completely unaware of the general

consternation behind the scenes.

Even most of the locals and club members were probably only aware

of rumours of certain difficulties.

Although only two sentences, the announcement built on a swell of

anticipation as Duke’s surfing skills had been highlighted in many

of the articles appearing in the lead-up to the tour. Furthermore,

it is possible that some copies of posters, prepared by the

Swimming Association to promote Duke’s appearance at the Domain

Pool in January, were already in limited circulation.

These featured an impressive illustration of Duke riding his

surfboard at Waikiki. It is reasonable to assume that these were

highly collectable, and they may have often disappeared

mysteriously when posted in a public place.

The design was lifted directly from the poster for the Mid-Pacific

Carnival at Honolulu in early 1914.

However, for the Domain poster the illustration had been

hand-coloured.

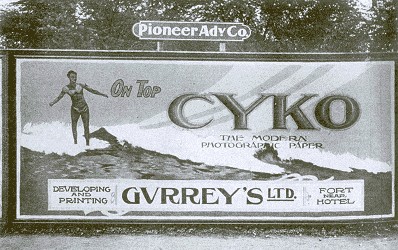

It was based on a photograph by A. R. Gurrey Jr., taken in 1910

and, thereafter, it was extensively reprinted or referenced. Its

first commercial appearance was on a large bill board advertising

“CYKO, The Modern Photographic Paper,” available from Gurrey's

Developing and Printing, Honolulu.

In 1911, the photograph was on the front cover of the first

edition of Alexander Hume Ford’s The Mid-Pacific Magazine.

That is, the Alexander Hume Ford who surfed with Jack London

in1906, was told surfboard riding was banned in Sydney in 1907,

and then returned to Waikiki to help found the Outrigger Canoe

Club in 1908.

Sydney’s response of to the announcement was swift and one

journalist suggested that the crowd that morning at Freshwater

numbered almost 3000.

(To this day, well-meaning and enthusiastic journalists greatly

over-estimate the number of spectators at a surfboard riding

events)

The crowd was to be severely disappointed and by 11 o’clock, it

was clear that the there would be no surfboard riding to be seen

today.

By the evening, the news of the cancelled exhibition was all over

the Sydney, as reported by W. F. Corbett in the later editions of

The Sun. Corbett noted that the Swimming Association confirmed

that Duke's" first appearance in public will take place at the

Domain” and it was “controlling his visit to this country.”

Furthermore, “the announcement of any other arrangement with

Kahanamoku as the central figure has not that body's authority."

A week later in The Referee, Cecil Healy suggested

that, rather than an uncomfortable conflict between the Swimming

Association and Freshwater, the postponement of the event was the

result of a simple miscommunication.

Healy seemed to imply that the event had been organised jointly by

the Association and Freshwater, and their intention was to present

a strictly “a private exhibition” for the press.

The announcement forwarded to the Herald, and presumably to the

other newspapers, was meant to encourage it to send a reporter,

and not intended for publication.

This is highly plausible, the only difficulty being that as it

appeared several days after the crisis had passed.

As such, Healy had the benefit of hind-sight and this explanation

may have served to dispel any residual ill-feelings, at least

between the officials and managers.

Whatever the facts, this was of little consolation for an

inconvenienced and disappointed public.

The use of the word “postponement” by Healy was critical.

Corbett’s article had strongly implied that the situation was

emphatically resolved, and any appearance by Duke before the

swimming carnivals was virtually impossible.

The negotiations probably continued well into the morning.

As the announcement had appeared in Tuesday’s Herald, the option

of submitting a retraction that afternoon, to be published on the

Wednesday morning, does not appear to have been considered.

The compromise position was to first, cancel today’s event.

Secondly, without any public announcement, another exhibition was

scheduled for the following day.

And finally, a public exhibition at Freshwater was to be held on

the morning of 10th January, with possibly a visit to Manly in the