|

surfresearch.com.au

polynesian surfriding : hawaii, 1778 |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

5.1 An early description by Charles Clerke, Captain 'Resolution' (1) recorded at Waimea, Kauai or Kamalino, Ni'ihau between 19th January to 2nd February, 1778 notes:

"...a thin piece of Board about 2 feet broad & 6 or 8 long, exactly in the Shape of one of our bone paper cutters; upon this they get astride with their legs, then laying their breasts along upon it, they paddle with their Hands and steer with their Feet, and gain such Way thro' the Water, that they would fairly go round the best going Boats we had in the two Ships, in spight of every Exertion of the Crew, in the space of a very few minutes." (2)

Although Clerke does

not indicate the use of the boards for surfriding, but rather notes their

effective

use as paddleboards, no doubt they served both purposes.

The use of, even

a small, board is a significant advantage to paddling speed relative to

swimming speed.

Furthermore, employed

as a floatation device a board can significantly reduce fatigue.

Generally, the larger

the volume of a board, the greater the improvement in padding speed and

distance.

Also note that if

the board's volume allows the rider to sit above the water line while stationary,

there is a marked improvement in their field of vision.

A 18th century bone

paper cutter was a thin straight blade with bevelled edges and rounded

at both ends.

Unlike the later

pointed letter opener, the 18th century item was designed to break the

wax that sealed correspondence, and not cut the paper. (3)

In modern parlence,

the shape of a wooden ice-confection stick.

To summarize Clerke's description: a thin timber board about 24'' wide and with length varying between 6 and 8 feet, the template is essentially parrallel with rounded nose and tail.

5.2 A second report describing boards used for paddling is by William Ellis, Surgeon's Mate, 'Discovery', at Waimea, Kauai, January 1778.

"Besides these, they have another mode of conveying themselves in the water, upon very light flat pieces of boards, which we called sharkboards, from the similitude the anterior part bore to the head of that fish." (4)

In contrast to Clerke,

Ellis describes the boards with a a semi-pointed nose, similar to the profile

of a shark's head.

Ellis's comment

on the boards' weight ("very light"), is either based on him personally

handling an example or he has noted a similar report by another crew member.

The boards may have

been built from willi willi (Erythrina sandwicensis) or breadfruit

(ulu)

(Artocarpus incisus).

These timbers will

further discussed at length, below.

5.3

George

Gilbert, midshipman 'Resolution', also observed Hawaiians paddling

boards as an alternative to transportation by canoes.

In February 1779,

Gilbert reported from Kealakekua Bay, Hawai'i:

"Several of those Indians who have not got Canoes have a method of swimming upon a piece of wood nearly in the form of a blade of an oar, which is about six feet in length, sixteen inches in breadth at one end and about 9 at the other, and is four or five inches thick, in the middle, tapering down to an inch at the sides." (5)

Gilbert's description,

while indicating a length at the bottom range of Clerk's account,

varies in the narrow width and a tapered template ("sixteen inches in

breadth at one end and about 9 at the other").

Modern surfboard

designers describe this as a foil template. (6)

The board possibly

features a rounded nose: "in the form of a blade of an oar".

The report of the

board's thickness ("four or five inches thick") is significant and

not indicated in the other contempoary reports.

The convex cross-section,

"tapering down to an inch at the sides", indicates a bevelled rail

-probably not square and possibly either a round or a chine rail. (7)

Subsequent commentators

regularly report this feature and it may be implied by Clerke's "exactly

in the Shape of one of our bone paper cutters", 2.1 above.

.

The account later

implies that members of the crew attempted to paddle the boards, without

success.

"These pieces of wood are so nicely balanced that the most expert of our people at swimming could not keep upon them half a minuit without rolling off." (8)

This is consistant with Ellis' comment (above) that indicates the boards have been examined closely by some crew members and must have been held to report the weight.

5.4

Apart from the written accounts, Cook's artist, John Weber in "A

View of KaraKakooa, in Owyhee" illustrated a Hawaiian paddling

a surfboard for transportation as an alternative to canoes, as described

by Clerke, Ellis and Gilbert, noted above.

An engraving by

W. Byrne, based on an original drawing at Kealakekua Bay, 17 January 1779,

was printed in the official account of the voyage, Plate 68.

The board and paddler

is depicted in the image below, cropped from the much larger work.

|

detail from "A View of KaraKakooa, in Owyhee." John Webber. An engraving based

on an original drawing at Kealakekua Bay, 1779.

|

5.5

The

first report of surfboard riding activity in Hawaii, is by David Samwell,

Surgeon's Mate 'Discovery', at Kealakekua Bay, Hawai'i, dated January

22, 1779.

Samwell describes

the board as:

"a thin board about six or seven foot long & about 2 broad" (10)

This is similar, if a little shorter, to the dimensions as estimated by Clerke, above.

5.6

Another

journal entry descibing board riding is from Kealakekua Bay,

Hawai'i, March 1779, by Lt. James King of "Resolution" .

Following Cook's

death on the 14th February 1779, King was promoted to first lieutenant

and his duties included continuing Cook's log.

King describes the

board as:

"an oval piece of plank about their Size & breadth" (11)

This appears to indicate

a board approximately 6ft long and 20'' wide with a rounded nose and tail

template.

The description

is consistant with that of Clerke, above.

5.7

Following

the return of Cook's third Pacific expedition to England on the 4th October

1780, the Admiralty selected the Reverend John Douglas to edit the logs

and journals to prepare them for publication.

The first edition

was published in 1784. (12)

In an entry for

Kealakekua Bay, Hawai'i, March 1779, a surfboard is briefly described

as:

"a long narrow board, rounded at the ends" (13)

Despite the similarity

in the two surfboard descriptions, there are significant differences between

the two accounts of surfriding activity attributed to James King.

Finney and Houston(1996)

caution that

"... the official

publication ... was heavily edited by ... Douglas ... adding marterial

of his own and from other accounts of the voyage." (14)

5.8

It

should be noted that these reports provide a limitted perspective of Hawaiian

surfing at the time.

Although the reports

only indicate prone surfriding, undoubtedly native skills far surpased

this activity and there was a greater range of board designs than those

observed.

In total, the ships

of Cook's third pacific expedition were anchored in Hawaiian waters for

49 days.

The longest stay

was at Kealakekua Bay, Hawai'i (30 days) but much of the return visit would

have been

preoccupied with

Cook's violent death and its aftermath. (15)

It would appear

that the most observations were probably at, or around, Kealakekua Bay.

Note that there

are no reports from Hilo Bay on Hawaii or Wakiki on Ohau, apparently the

two major centres of

ancient Hawaiian

surf-riding. (16)

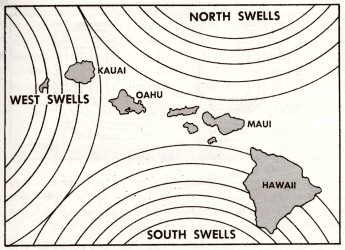

Also note that at

this time of the year the predominant swell direction is the famed winter

swells originating in

the North Pacific,

and the extended anchorages were all on the southern coasts.

Generally, the southern

coasts best surfriding conditions are with the summer swells from the southern

ocean,

although some may

also be exposed to winter swell from the west. (17)

If the Kona coast

surfriders had been questioned as to the suitability of the conditions,

their response may have

translated approximately:

"You really missed it - you should have been here six months ago!" (18)

The one northern

anchorage, at Waimea Bay on the island of Ohau, was only for one night

(27 - 28 February

1779).

Given the modern

reputation of this location for big wave surf-riding at this time of the

year, it appears that

Clerke's decision

to relocate to Waimea Bay on Kaui was sensible.

For a dramatic account of Polynesian sufriding on a coast explosed to seasonal swells, see James Morrison's account on Tahiti in 1788, 3.8.

5.9

It is important to note that all hand shaped surfboards are unique and

any general reports of a board's characteristics as these would not indicate

specific individual features.

Also note that craftsmen

working in timber are likely to be guided to some extent by the specific

chracteristics of a particular tree or piece of timber, for example splits,

knots or woodrot, that may determine a board's dimensions.

Furthermore, board

design could be significantly restricted if, as previously suggested, "the

recycling of damaged canoes into smaller craft may have been practised

in the formative era of ancient surfboard construction". (3.4)

Finally, board design

may fluctuate with local conditions and/or local precedents.

5.10

The

reports by Cook's crew are summarized in the following tables.

| 5.10a

'Paddling' |

|

|

|

|

| Location |

|

|

|

|

| Description |

|

|

|

|

| Length |

|

|

|

|

| Width |

|

|

|

|

| Thickness |

|

|

|

|

| Weight |

|

|

|

|

| Template |

|

|

|

|

| Nose |

|

|

|

|

| Tail |

|

|

|

|

| Rails |

|

|

|

|

| 5.10b

'Surfriding' |

|

|

|

| Location |

|

|

|

| Description |

|

|

|

| Length |

|

|

|

| Width |

|

|

|

| Thickness |

|

|

|

| Weight |

|

|

|

| Template |

|

|

|

| Nose |

|

|

|

| Tail |

|

|

|

| Rails |

|

|

|

5.11

The accounts of Hawaiian surfboards detail four cases of their use for

transportation (Clerke, Ellis, Gilbert and Weber) and three cases of prone

surfriding (Samwell, King and King as edited by Douglas).

Undoubtedly, the

boards observed as 'paddleboards', were also used, if not intended, for

surfriding.

In all cases, the reports refer to adult (on one occassion, tandem) paddlers or riders and those that indicate an empirical length, record a consistent six foot or longer, one indicating a maximum of eight feet.

Three reports indicate

a width of about 24 inches, one at 20 inches.

Since maximum board

width is essentially determined by the width of the paddler's shoulders,

these boards probably fell in the range of 20 to 24 inches.

Two reports indicate

the board is ''thin'' , one as ''flat'' and one notes the

lightweight of the timber.

The latter feature

may indicate the use of willi willi, see below.

The nose is reported

in four accounts as "round", and the tail as "round" in three

accounts.

Samwell's distinct

description of the nose profile as "the similitude the anterior part

bore to the head of that fish (a shark)", resembles some early

examples held by the Bishop Museum.

Ellis implies the

nose and tail have identical profiles, but in the other cases both ends

may be "rounded" but with differrent profiles.

5.12 Gilbert's account contrasts substantially to the other reports yet, as the most detailed, it cannot be discounted.

While the length

conforms to other accounts, the width measurements may be in dispute.

It is difficult

to know whether the 16 inch width ("sixteen inches in breadth at one

end") indicates a measurement at the nose, and the maximum board is

somewhat wider, or 16 inches is the maximum board width.

Certainly the dimensions

("and about 9 at the other") indicate a foiled template which is not

recorded by the other observers.

Gilbert's dimensions

certainly indicate the board in cross-section is convex, at least on one

side if not both.

This feature is

possibly infered by Clerke (3.1) who noted "exactly in the Shape

of one of our bone paper

cutters" (my

emphasis), but is not indicated in the other reports.

A convex cross-section

is a noted feature of many examples of ancient Hawaiian paddles. (see 2.3,

above)

The noteable difference

is the thickness.

Many later reports,

and most known examples, of boards of this length note their thinness,

with measurements of one and a half inches or less. (19)

Gibert's specific

report "four or five inches thick, in the middle, tapering down to an

inch at the sides" , contrasts markedly with (the more the general

term) "thin", as used by Clerke (2.1) and Samwell (2.5).

The difference is

significant and it is hard not to conclude from the sum of the reports

that there are two distinct designs identified.

One design is wide

and thin, the other a narrower and thicker board.

The rationale for two distinct designs may be the result of a number, or a combination, of factors.

i. The specific

chracteristics of a particular tree or piece of timber may determine a

board's dimensions.(2.9)

In this case it

might have been difficult to source trees of desirable width, and the volume

was adjusted by shaping a thicker board.

Alternatively, if

the source timber was a lighter and structually weaker variety than the

common koa (that is willi willi or breadfruit), such a thickness may have

been considered necessary to retain strength.

Furthermore, a lighter

or structually weaker timber may be more susceptible to impregnation by

seawater and a thicker board may have reduced the possibility of wood rot.

ii. board design

may fluctuate with local conditions and/or local precedents. (2.9)

The narrower and

thicker design may have been deemed more suitable to specific wave riding

conditions.

A narrower board

may be more suitable for riding in a prone position, but it is speculation

if the thickness was preferred for waves with a gentle or a steep sloping

face.

Note that later commentators (20) have determined thickness (in excess of three inches) as a distinct feature of the olo board, the largest known design that reportedly extended to 18 feet in length.

Beaglehole,

J.C.: The Life of James Cook.

Stanford University

Press Stanford, California. 1974, page 675.

Original publisher

: A. & C. Black, Ltd. London, 1974.

A further re-allocation

of duties followed the death of Clerke in the Nothern Pacific in August

1879.

Beaglehole:

Cook

(1974),

pages 682-683.

2.

The

(unaccredited) quotation was contributed in a personal email by Patrick

Moser, Drury University, July 2006.

Sincere thanks to

Patrick Moser for his substantial contribution to this subject.

3. Conversation with Scott Carlin, Curator, Vaucluse House, Sydney, March 2006.

4.

Ellis, William : An Authentic Narrative of a Voyage Performed by Captain

Cook and Captain Clerke, in his Majesty's Ships Resolution and Discovery,

During the Years 1776, 1777, 1778, 1779 and 1780; In Search of a North-West

Passage Between the Continents of Asia and America.

Including a Faithful

Account of all their Discoveries, and the Unfortunate Death of Captain

Cook, Illustrated With a Chart and a Variety of Cuts.

G. Robinson, J.

Sewell and J. Debrett, London.

Two Volumes. 1782.

Page?

The quotation was

contributed in a personal email by Patrick Moser, Drury University, July

2006.

Sincere thanks to

Patrick Moser for his substantial contribution to this subject.

The publication

details were prepared by Alan Twigg,

http://www.abcbookworld.com/?state=view_author&author_id=4312

5.

GeorgeGilbert,

quoted in:

Dela

Vega, Timothy T. (editor): 200 Years of Surfing Literature - An

Annoted Bibliography

Published by Timothy

T. Dela Vega.

Produced in Hanapepe,

Kaui, Hawaii. 2004 (ed, 2004), page 15.

Note, however, the

quotation omits the final phrase "to an inch at the sides."

The full quotation

was contributed in a personal email by Patrick Moser, Drury University,

July 2006.

Sincere thanks to

Patrick Moser for his substantial contributions to this subject.

The original quotation

is possibly in

Holmes, Christine(editor):

Captain

Cook's Final Voyage: The Journal of Midshipman George Gilbert.

Caliban Books, Horsham,

Sussex.

University of Hawaii

Press. 1982. Page?

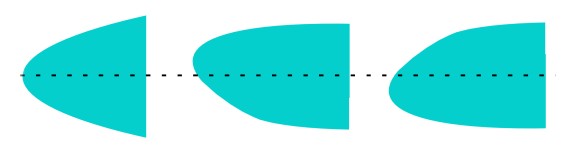

6.

Surfboard

rails, the left and right edges of the board’s template, blend together

the deck and bottom shapes.

Rail shape is basically

determined by the board thickness at any given point and in many examples

the rail profile subtlely varies through a range of shapes longitudinally

from the nose to the tail.

They are the most

difficult feature of surfboard design to describe and/or measure.

There are three

basic rail shapes:

| Square.

Most common on hollow timber boards, c 1935-1955. |

Round.

A continuous curve from deck to bottom. |

Chine*.

Deck and bottom profiles meet at a distinct edge. |

Rail profiles also vary in elevation, relative to the centre of the board's profile between the deck and bottom.

|

Mid

Rail.

|

|

Low Rail. |

7.

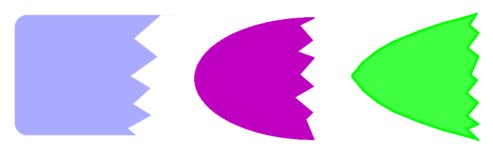

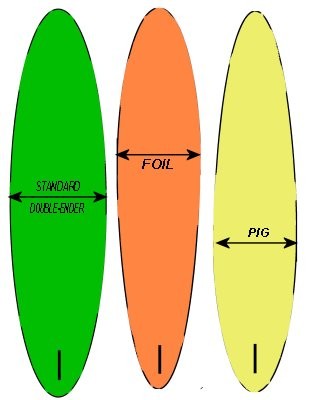

There

are three basic template shapes, essentially determined by the location

of the widest point.

Adjustment of the

wide point varies the ratio of nose area to tail area.

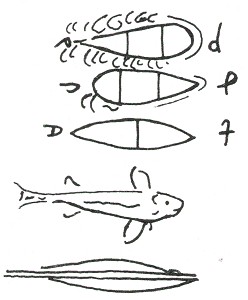

| template /

plan shape / outline / profile

1. The two external curves that proscribe the outer dimensions of a board when viewed in plan, either the deck or the bottom. Standard (or

Common).

Foil.

Pig.

www.surfresearch.com.au glossary |

|

| These three basic

designs were possibly first identified has having different hydrodynamic

proprties by Leonardo da Vinci, circa 1515.

Image right:

From the top: Foil,

Pig and Double-Ender.

|

|

8. Gilbert in Dela Vega et. al: Surf Literature (2004), page 15.

9.

Cook,

James and King, James: A Voyage to the Pacific Ocean Undertaken by Command

of his Majesty For Making Discoveries in The Northern Hemisphere Performed

Under Captains Cooke, Clerke, Gore in Years 1776, 1777, 1778, and 1780,

being a copious and Satisfactorary Abridgement.

Douglas, Reverend

John (editor)

G. Nicholl and T.

Cadell, London, 1784. Plate 68.

The image may also

apear in subsequent editions, see publishing details below, point 10.

The full and/or

the cropped image have been extensively reproduced, including:

Beaglehole,

John C. (editor) : The Voyage of the Resolution and Discovery 1776 -

1780.

Cambridge Hakluyt

Society, Two Volumes.

Volume 1, 1967.

Plate/page???

Finney, Ben and Houston

James D.: Surfing – The Sport of Hawaiian Kings.

Charles E. Tuttle

Company Inc.

Rutland, Vermont

and Tokyo, Japan.1966. Plate 1, between pages 14 and 15.

Margan, Frank and

Finney, Ben R.: A Pictorial History of Surfing.

Paul Hamlyn Pty

Ltd, 176 South Creek Road,

Dee Why West, NSW

2099. 1970. pages 20 - 21.

Young, Nat with McGregor,

Craig: The History 0f Surfing.

Palm Beach Press,

40 Palm Beach Road,

Palm Beach NSW 2108.

1983. page 33.

Lueras, Leonard:

Surfing

- The Ultimate Pleasure.

Workman Publishing

1 West 39 Street

New York, NY 10018. 1984. pages 44 - 45 and 47.

Kampion, Drew:: Stoked

: A History of Surf Culture.

General Publishing

Group

Los Angles. 1997.

Second edition 1998. page 32.

Finney,

Ben and Houston, James D.: Surfing – A History of the Ancient Hawaiian

Sport.

Pomegranate Books

P.O. Box 6099 Rohnert

Park, CA 94927,1996, Appendix B, page 12.

Dela Vega et. al: Surf Literature (2004), page 15.

10.

Quoted

in:

Aughton, Peter :

The

Fatal Voyage - Captain Cook's Last Journey.

Arris Publishing

Ltd. 12 Main Street, Adlestrop, Moreton in Marsh

Gloustershire GL56

0YN. 2005. Pages 146 and 147.

Referenced as "Samwell

page 1164".

11. Beaglehole: Voyages(1967) Volume 1, 1967, page 268.

The quotation is

reprinted in

Finney

and Houston: Surfing (1996) Appendix B. Page 97.

12.

Alan

Twigg details the history of the publication of Cook's journals on his

web page, The British Columbia Bookworld Author Bank:

"The British

Admiralty published an edited account of Cook’s voyages in three quarto

volumes and a large atlas in 1784-1785, now generally known as 'A Voyage

to the Pacific Ocean'.

The journals

were heavily edited by Dr. John Douglas, Bishop of Salisbury.

As commissioned

by the Lords of the Admiralty, Douglas embellished much of Cook’s original

journals with material gleaned from Cook’s officers.

In particular,

Douglas extrapolated from Cook’s reports of ritualistic dismemberment among

the Nootka, beginning the belief that the Indians engaged in cannibalism

when Cook had, in fact, described them as “docile, courteous, good-natured

people.”

Some of the more

sensational revelations added to the text were designed to encourage the

spreading of “the blessings of civilization” among the heathens and to

help sell books.

For almost 200

years Douglas’ version of Cook’s writings was erroneously accepted as Cook’s

own.

Cook’s journal,

with its bloody ending supplied by James King, proved popular.

Within three

days of its publication in 1784, the first printing was sold out.

There were five

additional printings that year, plus 14 more by the turn of the century.

Translations

were made throughout Europe.

The original

version of Cook’s journal was edited by J.C. Beaglehole and finally published

for scholars in the 1960s.

It reveals that

Cook was a somewhat dull reporter, more interested in geography than anthropology."

http://www.abcbookworld.com/

13. Cook and King: Voyage (1784) pages 145 to 147.

A second edition

compiled by another editor followed.

Cook, James and

King, James: A New, Authentic and Complete Collection of Voyages Round

the World, Undertaken and Performed by Royal Authority. Containing an Authentic,

Entertaining, Full, and Complete History of Capt. Cook's First, Second,

Third and Last Voyages.

Anderson, George

William (editor).

(London, 1784-1786).

Several translations

were published, one example being

Neueste Reisebeschreibungen;

oder, Jakob Cook's dritte und letzte Reise . . . in den Jahren 1776 bis

1780.

Nuremberg, 1786.

The quotation is

reproduced in

Finney

and Houston: Surfing (1996) Chapter 3. pages 36-37.

14. Finney and Houston: Surfing (1996) Footnote, Page 32.

15.

Robson,

John: Captain Cook's World - Maps of the life and Voyages of James

Cook R. N.

Random House New

Zealand

18 Polard Road,

Glenfield, Auckland, New Zealand. 2000.

Information specifically

relevant to Hawaii is on pages 154 to 155, pages 159 to 160 and the

maps 3.12, 3.23,

3.24 and 3.25.

This is a unique

work with a wealth of information in the form of maps, providing a wonderful

geographical

context to Cook's

voyages that is simply not possible from written accounts.

16.

Finney

and Houston: Surfing (1996) pages 28 to31.

Eight ancient surfing

locations are identified at Waikiki and Honolulu on Oahu (page 30), seven

at Hilo, Hawai'i (page 28).

17."Winter

(November-February)

swells are born from fierce storms in the north and west Pacific.

These powerful

swells generate strong surf along the NORTH, WEST, and EASTERN shorelines.

...

During summer

months (May-August), waves are generated from storms located in

the south Pacific where winter is in full force.

These warm, blue

swells will cause surf along any shoreline with a southerly exposure."

Wright, Bank (Wright

Jr, Alan B.): Surfing Hawaii

Mountain and Sea

P.O. Box 64 Redondo

Beach, California 90277. 1971 Page 9.

|

Illustration by Bill Penarosa. Wright,

Bank (Wright Jr, Alan B.): Surfing Hawaii

|

Edwards, Phil with

Ottum, Bob: You Should Have Been Here An Hour Ago

- The Stoked

Side of Surfing or How To Hang Ten Through Life and Stay Happy

Harper and

Rowe 49 East 33rd Street New York, NY 10016.1967

19.

Circa 1878, extremely thin boards were noted by John Dean Caton, who estimated

a thickness of "about three quarters of an inch thick."

Caton, John Dean:

Miscellanies.

Houghton, Osgood

& Co. Boston,1880, page 243

20.

The

earliest account that identifies the two distinct surfboard designs (one

"broad

and flat", the other "narrower") is by the native Hawaiian

historian David Malo, circa 1838.

Malo, David: Hawaiian

Antiquities (Moolelo Hawaii).

Bernice P. Bishop

Museum,

1525 Bernice Street,

Honolulu, Hawaii.

Originally composed

between 1835 and 1838.

Translated from

the Hawaiian by Nathaniel B. Emerson, 1889.

First published

1901.

Second Edition:

Special Publication 2, 1951.

Reprinted 1971,

1976, 1980, 1991, 1992, 1997, 2005, page 223.

The two designs are

identified by their Hawaiian names by another native historian John Papa

I'i, circa 1870:

"The 'olo' is

thick in the middle and grows thinner toward the edges."

and

"The 'alaia'

board, ... , is thin and wide in front."

I'i, John Papa: Fragments

of Hawaiian History.

Bernice P. Bishop

Museum,

1525 Bernice Street,

Honolulu, Hawaii. 968117

Originally printed

in a series of articles 1866-1870, written and published in the native

Hawaiian language.

First English translation

printed 1959.

Second printing

1963, Third printing 1973.

Revised edition

1983 as Special publication 70.

Second revised edition

1993. Sixth printing 1995, page 135.

Note that I'i also

identifies a third design ("The 'kiko'o' reaches a length of 12 to 18

feet") although its status is questionable and it may be a long vesion

of the olo.

For an expanded

discusion of John I'i's account, see 7.6 below.

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |