|

surfresearch.com.au

polynesian

surfriding : other islands

|

polynesian surfriding : other islands

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

surfresearch.com.au

polynesian

surfriding : other islands

|

The island

settlement was discovered in 1808 by Captain Folger in the

Topaz, who reported his surprising find

to the British

Admiralty.

However there

was little official interest in pursuing what was now merely

remnants of the mutiny.

Whereas

European influence on Pitcairn was principally evident in a

resurgent Christianity, Polynesian culture

maintained a

strong bond with the ocean, most notably a continuation of

surfboard riding in relatively difficult

conditions.

A number of

vessels visited the island before the Surry in 1821,

when the inhabitants were observed surfing on

small boards.

Crew member,

Dr. Ramsay reported:

"The

Capt returned and told me that after loading the boats

which was done by swimming through the

surf with

the fruit, they to his great astonishment amused

themselves by taking a flat board about 3

feet

long, on the upper side smooth and on the under a ridge

like a keel, and went out on a rock and

waited

till a large breaker came and when the top of it was close

on them, away they went with the

piece of

wood under their belly on the top of this breaker and

directed themselves by their feet into

the

little channel formed by the rocks, so that men the surf

left them they were only up to their knees

in water.

They are

very dexterous in keeping off the rocks which to us would

be inevitable death."

- page 7.

While the

Pitcairn surfboards were built of local timber, the

incorporation of a "ridge like a keel" appears to be

unique and is

not recorded in any of the reports of traditional surfboards

of Tahiti or the Hawaiian Islands.

It appears to

be a design feature intended to give the board directional

stability (commonly known as a fin and

usually

accredited to Tom Blake in 1935), developed by a combination

of the Tahitian native design and the

European

seaman's knowledge of boat building.

Alternatively,

there is a very remote possibility that it was added to give

board structural strength.

In 1823, a

British whaler, Cyrus, left two of her crew on

Pitcairn, John Buffett and John Evans, who provided an

injection of

European influence, but this was minor in comparison to the

significant social dislocation resulting

from the

arrival of Joshua Hill in 1831.

Due to the

pressure of an increasing population on the small island,

several attempts were made to relocate the

inhabitants

before there was a major relocation to Norfolk Island in 1856,

where the descents of the Bounty

mutineers'

continued their enjoyment of surfriding.

Ramsey, Dr.

David: The Scrapbook of the Log of the Ship "Surry",

Pitcairn Island April 1821.

Acquired from

The Pitcairn Islands Study Center : Historic Papers

http://library.puc.edu/pitcairn/studycenter/store/papers.shtml

Dutchman

Jacob Roggeveen, in command of three vessels, was the first

European to sight Rapanui on Easter Day in 1722.

He is said to have reported the islanders "swam out to

the visitors by the thousands, accompanied by small reed

skiffs."

Visiting Rapanui in 1827, Hugh Cuming noted the islanders swimming out to the vessel with supplies for the visitors, principally plantains (bananas), a practice reported on many other Polynesian islands.:

“On

standing into the Bay on the West side of the Island which

appears to be the most highly

cultivated,

we

saw the Natives collected in great numbers on the Rocks

and on nearing the shore

they took

to the Water and swam onboard each person having a small

Net or Basket or a Bunch of

plantians

on his Back for Sale or barter."

These goods were exchanged for fish hooks (made from metal) and timber, indicative of the lack of local resources:

"they where [were] particularly partial to Wood and Fish hooks for one only the[y] gave a Net or Basket full of Fruit or Vegetables."

The islanders' skill at swimming is common to many reports of early European contact across the Polynesian triangle:

"Swimming at which the[y] are very expert as I ever witness'd,"

Without acces to canoes, the Rapanui's had constructed diminutive craft made from small shrubs to assist their swimming in difficult conditions:

"when

the Sea becomes rough which occurd in the afternoon some

of them made use of small Balsas or Bundle of Flags about

2 Feet long, Six Inches thick at one End and tapering to a

point at the other.

this

the[y] place betwixt their legs to assist them in

Swimming"

While the

small "Balsas or Bundle of Flags" were not surfboards, they

were certainly an elementary floatation device of considerable

assistance.

Fischer

comments in his notes on the text:

"Cuming

further notes (MS pp.7-8) how the Rapanui make use of “small

Balsas or Bundle of Flags

about 2 Feet

long” that taper to a point at each end to assist them in

swimming out to the Discoverer,

this pora

(type of raft) was first mentioned by Lisiansky (1814:1:58).

(Footnote) 9.

In footnote 9, Steven Roger Fischer suugests the craft were of Polynesian origin and are not diretly related to the reed boats (pora) as used by ancient Peruvians:

"9. For

a physical description of this raft, see Métraux

(1940:208).

Pora were

also used for surf-riding.

Their use

most likely originated uniquely on Rapanui for want of

appropriate wood to construct

proper

vaka; i.e., they would probably not represent an

importation of similar Peruvian craft, as

Heyerdahl

has repeatedly suggested."

To be sure of a favourable reception they

brought us bananas, sweet potatoes and yams enveloped in

their reeds."

The swimmers also brought Petit-Thouars a most peculiar

wooden image representing a double head without body.

The eyes were inlaid with black obsidian inserted as

pupils into white bone.

Although he did not land, Petit-Thouars sailed close

enough along the coast to notice two types of dwellings.

He described the boat-shaped reed houses as large and

bright when seen from the sea, and added: "One could also

distinguish a very great number of small houses, black and

round like ovens."

| Amongst a plethora of

divergent theories as to the origin of the Easter

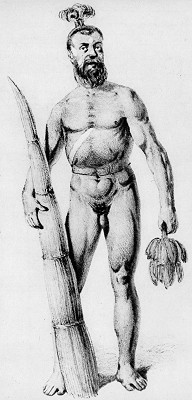

islanders, Hyderdahl noted: Thompson (1906) considered the Polynesians as one of the purest of all known people, and suggested they were Caucasians of the Alpine branch who had learnt the art of seamanship from the Phoenicians before they reached the Persian Gulf and pushed on to Polynesia by way of Sumatra. - Heyerdahl: Easter Island (1989) page 135. Also note: Métraux, Alfred:Ethnology of Easter Island. Bernice P. Bishop Museum Bulletin 160, Honolulu, 1940, page 208. Lisyansky, Yuri: Voyage round the world in the Ship Neva. Lisiansky, London, 1814. A man holding a

small pora on

Easter Island was

shown in an illustration by Radiguet.

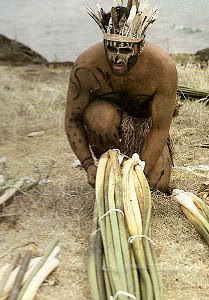

Published in du Dupetit-Thouars: Voyage around the World on the Frigate Venus, Paris, 1841.  Rapanui

islander padles a replica pora, circa 1985.

Heyerdahl: Easter Island (1989) page 21. Construction of replica pora, Rapanui, circa 1985

Heyerdahl: Easter Island (1989) page 21. |

|

|

5.4 Samoa

1861 George Turner : Surf Riding in Somoa. 1866 W. T. Pritchard : Surf Riding in Somoa. 1887. William Brown Churchward: My Consulate in Samoa: A Record of Four Years' Sojourn in the Navigators Islands. R. Bentley and Son, 1887. Reprinted by Southern Reprints, 1987. This work follows the travels of William Brown Churchward who, in 1882, became the British Consul in Apia, Samoa, and deputy commissioner for the western Pacific. It covers much of the history of Samoa over the period as well as covering a range of tropics from pigeon hunting and oratory, to religious rituals and tattooing. https://books.google.com.au/books/about/My_consulate_in_Samoa.html?id=1DpSxgEACAAJ&redir_esc=y Pages 137: On the water, surf riding is greatly in vogue when the sea is in a fit condition ... Page 139: the line of white surf appears to be closely dotted with brown spots, the heads of the bathers; Noted by Bob Green with thanks, 2020. 1901 Also note Dr. Augustin Kraemer: Die Samoa-Inseln Unfortunately the text is in German, the title translates as The Samoa Islands - Draft monograph with special reference to German-Samoa. However, it does include one photograph of surf riding in Samoa on page 401, right. Das Wellenengleitspiel roughly translates as wave play, the term in parentheses (Fa'ase'e) presumably the Samoa name. The image shows a large number of participants, some of whom have short body boards. |

No. 43 Das Wellenengleitspiel

(Fa'ase'e) - cropped. |

In an article for the Journal of Polynesian Society (1902, page 215), S. Percy Smith, detailed the canoes and fishing practices of the Nuie islanders, drawing parallels with other Polynesian craft:

Like all

Polynesians, the Niue people are expert canoe men.

Even to

this day they go in their little canoes right round the

island on fishing expeditions, on the weather side of

which rough seas are experienced.

Every

dark night fleets of canoes are to be seen along the

leeward coast with their bright torches ('hulu') engaged

in catching flying or other kinds of fish,—it is a very

pretty sight to see them.

A canoe

is a 'vaka', as it is in all other parts in some form of

that word; but 'foulua' is also a

canoe,

now applied to ships, which are also called 'tonga'.

The

canoes have outriggers, which are fastened by two arms to

the canoe itself.

The hull

is dug out of a log, with a topside lashed on and enclosed

for a space both fore and aft.

The seams

are caulked with a hard gum called 'pili', and are often

ornamented with shells and a little very rough carving.

The Niue

canoes are more like the 'va'a-alo-atu' or Bonito canoes

of Samoa than any others I have seen, but they are not so

well-finished nor so long.

A Niue

canoe is from 12 feet to 25 feet in length, about 18

inches or 2 feet deep, and somewhat less in width.

They

carry from one to three or four people.

The

outrigger is called a 'hama'; a double canoe is

'vaka-hai-ua', but not now in use.

The

paddles are termed 'fohe', and are shaped as seen in Plate

6.

With

these the canoes can be propelled at a considerable pace,

and they sometimes sail, the sail being a 'la', the mast a

'fane'.

The

natives manage their craft very adroitly in coming onto

the reef in rough weather, for at that time the little

chasms ('ava') in the reef are not available for landing

purposes.

The final comment, "manage their craft very adroitly in coming onto the reef in rough weather", probably indicates some form of canoe surf riding, a familiar practice across Polynesia.

In a section on Amusements (page 217), Smith notes:

"Surf-riding was another amusement, called 'Fakatu-lapa' or 'Fakatu-peau', which again is common to the race everywhere, but seems to have been practised more in Hawaii than elsewhere."

Smith, S.

Percy: Nuie Island and Its People.

Journal of

Polynesian Society, Volume 11, Number 4, 1902, pages

195-218.

| 5.6 Marquesas Islands E. S. Craighill Handy notes: Surf riding (hoko) was a sport for men, women, and children, where there were beaches that made it possible. Surf riders never stood, erect as in Hawaii. The surfboard was called papa a'a tai. Presumably referring to body-surfing, he also notes: Dordillon gives pakoao as a term used for an amusement participated in by two people, one being borne inshore on the crest of a breaker while another person, coming from the shore, passed under him. See Handy, E. S. Craighill: The Native Culture in the Marquesas, 1923. |

Kennedy,

Donald Gilbert: Memoir No. 9. Supplement to the Journal

of the Polynesian Society.

Field

notes on the culture of Vaitupu Ellice Islands.

Journal of

the Polynesian Society, Volume 41, Number 9, 1932, pages

321 to 328.

In 1912, a goup of Ellice islanders demonstrated their surfing skill, and some native traditions, at a Sdydney surf carnival:

A

successful surf carnival was held at North Steyne, Manly

on Saturday afternoon, 28 December 1912.

The

display was witnessed by 15,000 spectators.

...

One of

the prinipal attractions was the presence of a team of

native swimmers from the Ellice Islands.

They

entertained the crowd with their quaint songs and war

dances, combined with clever exhibitions of surf and boat

displays in the breakers.

139.

Sydney Morning Herald 30 December 1913, Daily Telegraph 30

December 1913.

- S&G

Champion: Drowning,

Bathing

and Life Saving (2000) page 177.

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |