surfresearch.com.au

r.c. pennie : why gays don't surf, 1981.

r.c. pennie : why gays don't surf, 1981.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

surfresearch.com.au

r.c. pennie : why gays don't surf, 1981. |

|

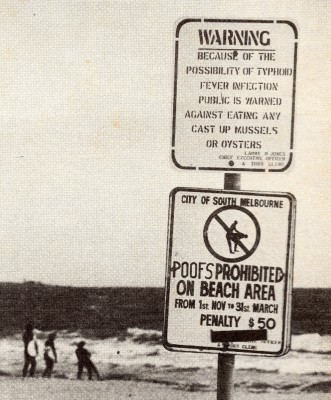

Why

Gays Dont Surf- or do they?

By R.C. Pennie Clustered together like archetypal chickens in

a barnyard coop, the half-naked, sun-bronzed group

of young men constantly eye the scene and

continually evaluate the competition.

Highly aware of each other and of the

special bond which membership in their

predominantly male group allows them, they share a

sense of community and social identity distinctly

different from

that experienced by other males their age. Sexual

overtones dominate the group, but sexual

segregation is a highly ingrained social norm.

They relegate women to an inferior status, and for the most part, these young men appear to prefer the company of other young men. No, these people are not members of the gay community who cruise the Hollywood discos in search of the ultimate orgasm. Rather, they are members of the surfing community who cluster together on Southern California beaches in quest of the ultimate wave. Both the gay community and the surfing community have much in common. Each practices sexual segregation — gays primarily for sexual reasons, and surfers merely because they consider women inadequate on the waves. Same-sex bonding which goes beyond simple friendship, but which is not necessarily overtly sexual, is rampant among both groups. Both gays and surfers place an unfortunately strong accent upon the "advantages" of youthfulness, and both place an over-emphasis upon the physical and material worlds. |

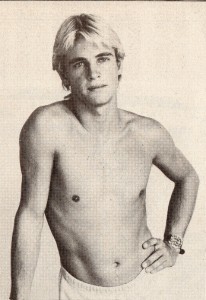

Photo

Pennie

|

|

Selling

With Surfing

Mark Coleman- Centrefold

Mark

Coleman

Photographs

by Paul Ryan

|

|

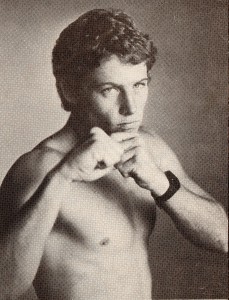

Peter Phelps, page 21. |

|

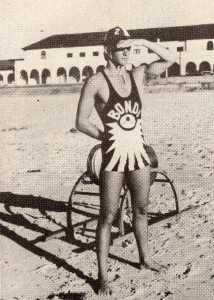

| Photograph: Bill Bachman Tracks May, 1982, page 2. |

|

Tracks Number 124 January 1981. Understanding the New Materials. By Bob MacTavish Windsurfing - Are you ready for it? By Bob MacTavish Why Gays Don't Surf- or do they? By R.C. Pennie |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|