surfresearch.com.au

fred van dyke : the peril of surf, 1968

fred van dyke : the peril of surf, 1968

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

surfresearch.com.au

fred van dyke : the peril of surf, 1968 |

| Surfing in California, 7 February 1938. | California Surfing, 26 August 1940. | Aquatic Adventure Down Under, 15 September 1958. | Riding the Wild Waves, 24 May 1963. |

| Dick Dale, King of "Surfing Music", August 30, 1963. | Skateboards, June 5, 1964. | Joyce Hoffman-surfing champ, 14 October 1966. | (Surfing Photos), 20 March 1967. |

| Murf the Surf, and jewel robbery, 21 April 1967. | The Peril of the Surf, March? 1968. | Big Surf- Surf pool in Arizona, 6 March 1970. |

| Page 33 |  |

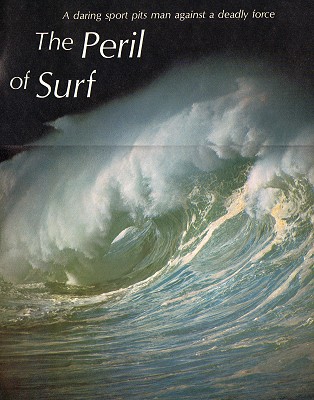

A daring sport pits man against a deadly force The Peril of Surf Photograph by Leroy Grannis, Waimea Bay shore-break. |

|

Page 34

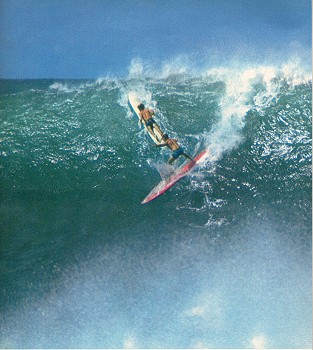

The moment of

exhilaration — and

sometimes disaster

And few sports are more daring than the act of riding this wild and deadly turbulence on a slim board. Surfing requires an amount of insanity ranging from ordinary foolhardiness to the more extreme mental imbalance described on pages 42-47. Racing down the precipice (above) of a crackling, thunderous mountain of water is one of the most exhilarating experiences known to man—and it can sometimes mean engulfing disaster (pages 38-40). On the North Shore of Oahu, Hawaii, where most of these pictures were taken, the surf can attain its greatest power. Only in the past two decades have surfers dared to ride the monster waves of The Banzai Pipeline and some of the other North Shore maelstroms. One of the first, Dick Cross, was overwhelmed by a 30-foot thunderer. His body was never found. As if dropping off

the edge of a precipice, two surfers take the

plunge.

Photograph by Dr. Don James, Waimea Bay. |

|

Page 35

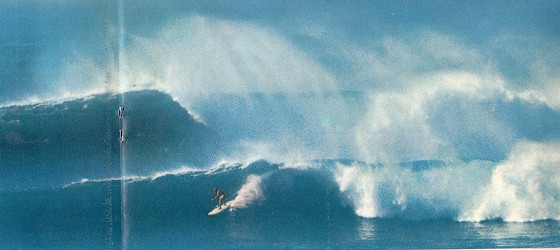

Riding one

in a set of waves (above), surfer risks

inundation by the next.

Photograph by Dr. Don James, Sunset Beach. |

Another

scoots away from a toppling

mountain.

Photograph by Ron Church, Sunset Beach. |

| Pages

36-37 |

|

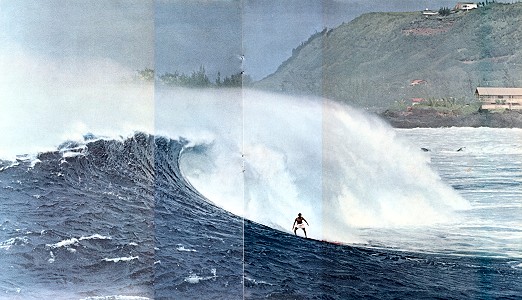

Just

ahead of the mountain crest,

a surfer rides past Waimea's rocky shore. Eddie Aikau, photograph by Dr. Don James. |

|

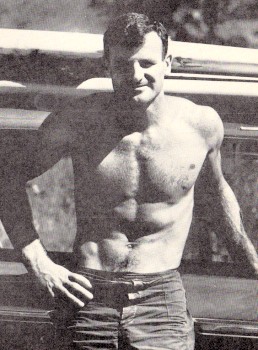

Author

Van Dyke was one of the pioneers in daring

the huge Waimea Bay waves and has been consultant and actor in many surfing movies. He teaches at Punahou School in Oahu, and thus can still surf whenever school is out. [Photograph by George Silk] |

|

Page 47

|

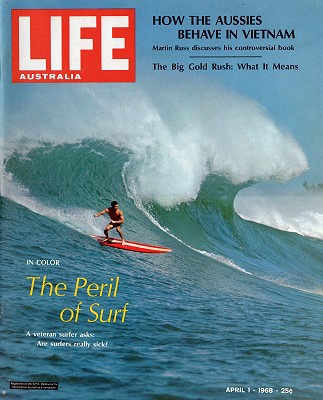

Life

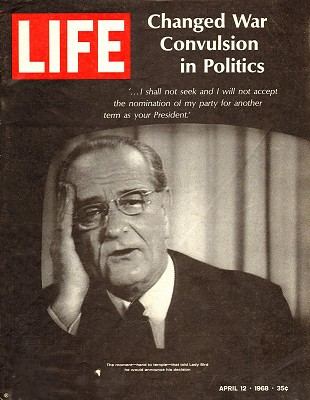

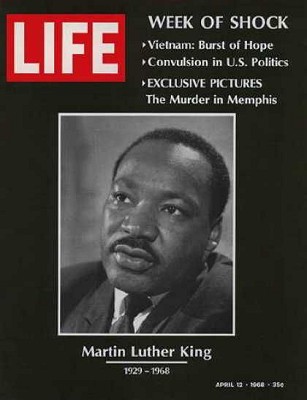

Australia, 1 April 1968. In Color: The Peril of Surf A veteran surfer asks: Are surfers really sick? Cover photograph of Sunset Beach (Waimea Bay?) by Neil Leifer for Sports Illustrated. Note the surfboard wake far inside the surfer on the red board. A second surfer has been cropped out of the shot. Articles in the International edition often appeared in the US edition, usually a week or two before. I cannot confirm if this was the case with this article. Below: Life Magazine 1 April 1968. First cover featuring President Lyndon Johnson, replaced by Dr. Martin Luther King following his assassination. The US edition originally featured President Lyndon Johnson on the cover, announcing that he would not nominate again for the Presidency, but was quickly replaced with a photograph of Dr. Martin Luther King following his assassination. ???? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|