morey - weber : surf contests, 1966

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

surfresearch.com.au

morey - weber : surf contests, 1966 |

| Morey, Tom: Surfer Tips Number - How to compete in 1966. | Weber, Dewey: The Makaha Contest is the Worst! |

Alternatively,

his

second innovation, "timed" surfing, had already been used in

Morey's Noseriding

Contest at Ventura in July 1965.

In this contest

the rider was timed by stopwatch while on the front 25% of the

board"

(designated by a coloured deck patch or band), with awards for

the longest

individual ride and the accumulated time over a maximum 14

waves.

In 1966, Morey

substantially

broadened the criteria-"surfers with the most accumulated time

standing

up on the board for wave opportunities will be the winners."

Essentially,

at its

core, this was a paddling contest- the surfer who rode the

longest distance

and was the fastest to paddle back to the take-off zone to

catch another

wave would accumulate the most points.

Incredibly,

from

a 21st century perspective, this approach, without any

consideration of

surfing performance, was regressive.

More

immediately,

it was in marked contrast to the intensive analysis of

performance surfing

currently explored by Australian competitors, the elite of

whom were soon

to arrive in California for the 1966 World Contest.

Perhaps bouyed by the enthusiasm and wide exposure of the earlier noseriding contest, it appears that no American competitor recognised the reactionary element of this format, put into use at the contest and attended. XXXXXXXXXXXX

Dewey Weber's article on Makaha voices many of the ongoing concerns of competition surfers about the structure and format of surfing contests at this time.

South

Africa

Ron Perrott's

article

on South Africa initiated the first major controversy for the

Surfer

staff.

In the body of

the

article, Perrott appeared somewhat apologetic for the policy

of Apartide:

"Half believing

some of the more distorted 'facts' on South Africa prevalent

in Australia,

I was completely unprepared for the friendliness and courtesy

received

from all sections of the community - whether Indian, Bantu or

white South

African." - page 65.

However, one

photograph

and its caption, "Durban's beaches are segregated so this

native youngster

can't join these three surfers ... for a little fun in the

surf" (possibly

added by the editor), produced a unprecedented response.

In susbequent

editions,

a number of readers suggested that rascism was an unsuitable

topic for

a surfing magazine.

Twelve months

later,

this controversy would appear relatively minor, compared to

the response

to We're Tops Now, by Australian, John Witzig.

The article was

originally published, with a far less confronting title, as

Nat

vs. Nuuhiwa ... How Do We Compare?

Surfing

World

Volume

8 Number 4, pages 10 to 13. January 1967.

In 1985, professional surfers buoycotted contests in South Africa in protest at that country's, now repealed, racial legislation.

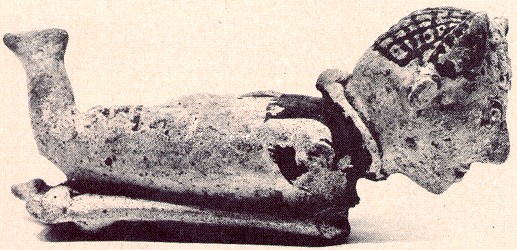

Inca Surfer

The ceramic

figure,

illustrated in the Pipeline column on page 75, has

never been referenced

in any of the subsequent literatue on the origns of surf

riding.

Articles

Rusty Miller

Interview, pages 25-31.

John Pennings:

Big

Drop at Little Avalon, pages 33-35.

Dewey Weber: The

Makaha Contest is the Worst!, pages 57-61.

USSA

1966 Ratings, pages 40-41.

Bill Cleary: Honolulu

Bay, pages 42-49.

Richard

Safaday:

Some

Like It Smooth, pages 54-57.

Extolling the

virtues

of a "smooth style", the article was perhaps a response to the

"aggressive"

style, as said to be promoted by Australian surfers.

Ron Perrott: "Crocodiles,"

Zulus and Surf Suid Afrika, pages 58-65.

Pipeline,

pages 75.

Griffin and

Stoner:

The

Banzia Pipeline, pages 83-90.

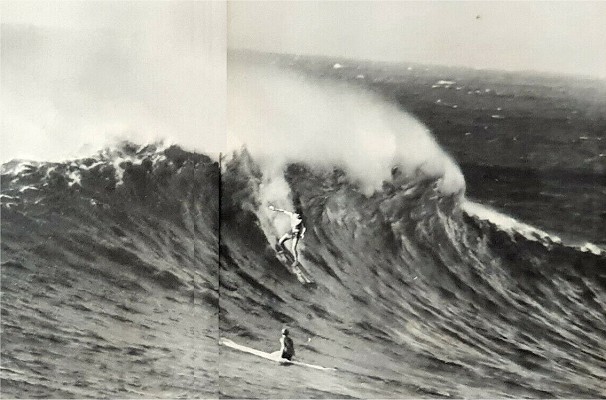

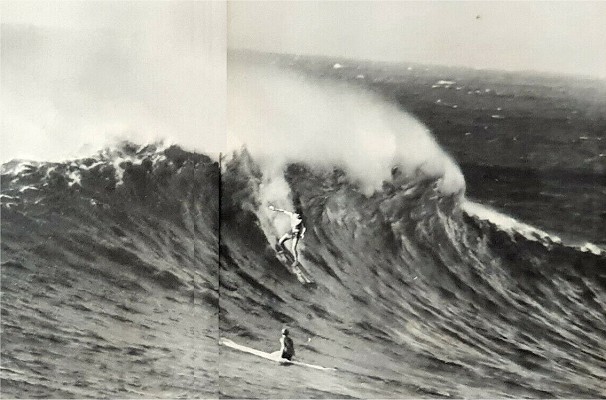

Rusty Miller and windy Sunset

Beach.

|

Page 30 Rusty Miller and Mickey Dora,

Sunset Beach.

|

Page 31  Rusty Miller, Makaha.

|

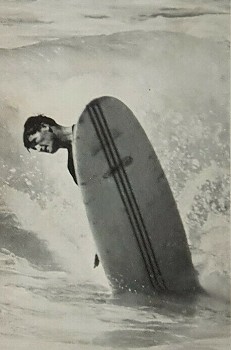

When Dewey

Weber

and the famous Makaha surf first met, it was obvious they

were meant for

each other.

With hot

sectIons

running into flat shoulders, Makaha was ideal for Dewey's

style.

A half dozen

quick steps and he was on the nose blasting through the

curl, and then

with incredible quickness, he was on the tail block jamming

a radical cutback.

Dewey's

reputation

as a hotdogger was already tops when the Makaha

International Contest was

established.

In 1956,

Dewey

first entered as a junior but ran into the kind of bad luck

that frequently

plagues Californians in the Makaha contest. Dewey had caught

his allotted

six waves and the consensus of surfers on the beach was that

the little

hotdogger from the South Bay had won hands down.

His flag

went

up on the beach- indicating that the allotted rides had been

completed-

so Dewey caught the next wave into shore. As he walked up to

the judge's

stand, he was as stunned as anyone to learn that he had BEEN

DISQUALIFIED

FOR RIDING ONE TOO MANY WAVES- the one he took into shore!

But

undaunted,

Dewey, like many top California surfers, returned several

times to the

Makaha contest.

Last year

Dewey

battled his way through the semi-finals into the finals

where he turned

on his famous hot-dogging style.

The

all-Hawaiian

judges picked him eighth.

Dewey has

much

better luck in non-Hawaiian contests and last year finished

fourth in the

United States Surfing Association competition.

Dewey's been

a top performer in major competition for ten years -a record

few other

surfers can match.

So Dewey's

pretty

well qualified to say:

Page 37

Yes, from the viewpoint of the guy out there in the water with the numbered T-shirt, the Makaha contest is the worst in surfing competition: a glaring example why surfing doesn't have the acknowledgment and recognition given other competitive sports on the international sports scene.

The contest

is

fine as a crowd event because that's exactly what it is.

This was

underscored

by a Honolulu newspaper, The Advertiser, that pointed out

during the last

contest that heat winners were the ones, in most cases, who

impressed the

spectators.

Little

mention

was given to the ability or performance shown by the

competitors and, in

fact, the newspaper article focused on incidents that were

"humorous for

the spectators."

This typical

news coverage underscores that crowd-pleasing ability

overshadows wave

ability and performance.

Twenty-four

competitors

jammed into the 30-minute heats pretty well assures the

spectators of humorous

incidents.

Among the

top-notch

competitors who year after year show up at the contest,

there's general

agreement that the regulation rules and scoring methods are

as outmoded

as the old redwood plank of bygone surfing days.

The Makaha

contest

is famous for its judging prejudices and yet year after year

the big name

surfers, and a lot of little name surfers, flock to Hawaii

to sign up for

a competitive meet that is actually detrimental to the

development of surfing.

It's

somewhat

puzzling, but I feel the contest is supported by surfers

strictly out of

enthusiasm for competition as well as the honor, fame and

now fortune that

goes to the winner.

Page 38

Page 39

Take my

case:

I competed last year because I really love surfing

competition and, too,

I felt that by competing I'm more qualified to form opinions

about the

contest and surfing as a whole.

As a

competitor,

Makaha's shortcomings became quite clear, and yet I was able

to see the

great potential of this contest as a truly international

meet.

Certainly I

would

be willing to give my full support if Makaha officials and

the competitors

would get together and- with the help of the United States

Surfing Association

- take advantage of the "opportunity to improve."

But with the

Hawaiian attitude, the chances of this are slim.

Surfing's

changed

an awful lot in the last ten years, and yet the regulations

governing last

year's Makaha championships differed only slightly from

those used in 1956

- the first time I entered the contest.

Some of the

obviously

out-moded regulations have been dropped, but plenty of

outdated principles

and even a few ambiguous rules have been added.

The

regulations

no longer limit the number of waves a contestant may ride,

but the mass

of contestants (last year, 550 signed up) make it virtually

impossible

for anyone contestant to ride "too many waves."

Discontinued,

too,

is the use of distance markers.

However,

distance

is still a key factor in accumulating points from the

judges.

Makaha's

regulauons

were set up thirteen years ago on the premise that big-wave

riding was

the only true test of surfing ability. Rules and scoring

system accommodated

the then prevalent method of scoring surfing contests on

wave size and

points were accumulated on the takeoff and ability to stay

trim with the

emphasis on the distance of the ride.

And so for

thirteen

years the emphasis has stayed on big-wave riding - giving

points for the

height of the wave and the distance of the ride.

Yet most of

the

Makaha competition has been run in small surf, but the

judges' system still

stresses the big wave, and no rules have been set up to

accommodate small

surf experts.

In order to

obtain

points, according to the Makaha rules, a surfer must stay in

the critical

part of the wave (the hook next to the breaking section) at

all times.

This may be

a

logical way to ride a big wave, but it can't be applied to

surf under eight

feet.

In small.

surf

keeping the surfer in the most critical part of the wave

limits his opportunity

to perform.

But any

Makaha

competitor who takes off, trims, limits his maneuvers and

rides all the

way to shore, racks up more points than the surfer who

leaves the most

critical part of the wave by cutting back, climbing,

dropping, even though

this surfer throughout the ride returns again and again to

the critical

portion of the wave.

Wally Froseith clarified, I think, Makaha's judging criteria when he said, "A surfer who catches a wave outside and rides it all the way to the shore definitely has more opportunity to perform and will, on the average get more points."

Wally's

statement

underscores the emphasis placed on distance and also points

out Makaha's

ambiguous judging premises. Officials have never explained,

as far as I

know, how the judges determine if "opportunity to perform"

is present.

And if it

is,

how do the judges determine if the surfer takes full

advantage of this

opportunity to perform?

"MAKAHA BASED ON LUCK"

This is

especially

unfair to surfers, considering there's usually a dozen, even

two dozen,

surfers in the water in each heat.

If a surfer

is

lucky enough to catch the largest wave in a 30-minute heat

and have it

all to himself - ride it all the way to the beach - his

score should not

be based on luck, but rather on his ability in taking

advantage of "the

opportunity to perform."

That is, how

well did the surfer execute his ability on the wave?

Just about

all

the contestants agree, as far as I know, Makaha's emphasis

on height of

wave ridden and the distance of the ride overshadows

contestants' performance

on the wave.

In my

opinion,

a true international champion doesn't purposely place limits

on his ability

to perform.

The

champion,

for my money, is a surfer who displays not only endurance,

judgment and

balance, but also is outstanding in the water.

He's the

surfer

who gets the most out of each and every wave by pushing his

ability to

perform to the fullest.

And so since

the rules at Makaha limit the ability to perform, I don't

feel they produce

a champion in the sporting sense of the

word.

There was

something

new in last year's contest: points were deducted for

unsportsmanlike conduct.

Now no one

can

argue that good sportsmanship has a place in every

competitive sport.

However, the

way this rule was applied at many contestants didn't even

know about it

until after completion of the competitive events.

And it's

still

not clear to me what guide lines were used by the judges in

determining,

in their opinion, what actually was a deliberate lack of

sportsmanship

in the water.

The judges

didn't

define what they meant by unsportsmanlike conduct, but they

still deducted

the points.

In many

cases,

surfers lost points when, attempting to get the most out of

the wave, they

accidentally bumped the rail of another competitor's board.

In the

judges'

opinion, this often was construed as a deliberate act of

unsportsmanlike

conduct and may explain why many surfers from the mainland

and Hawaii were

knocked out early in the contest, even though they showed

excellent ability

to perform- and weren't even aware of any deliberate

unsportsmanlike acts.

Surfing is

progressing,

I think, to the point where it can obtain the recognition

given other competitive

sports.

However,

even

though I'm one of surfing's greatest boosters, I can't

honestly .say that

the sport deserves that recognition now. Every competitive

sport, whether

a team or individual, has a governing body setting forth

uniform rules

and regulations that apply to meets.

And surfing

doesn't

have this.

Even though

the

sport does have such a body - the United States Surfing

Association.

The USSA

has,

and is continuing to make, a needed attempt to standardize

rules and regulations

used in surfing meets, but lack of support, principally by

the surfing

public and contest promoters, has blocked this.

And so it's

impossible

for the USSA to enforce uniform rules at every surfing meet,

whether in

California, Hawaii or New York.

A surfing

competitor

can surf in one contest under one set of rules and then

enter a contest

in another city or state where a completely different set of

rules apply.

This

condition,

I think, is uncommon in any other sport - yet it happens

every day in surfing.

I believe

every

competing surfer wants surfing to be accepted as a

competitive sport.

I know I do,

but we must remember that to reach that degree of

sophistication, surfers

must strive for the quantities and qualities found in other

sports.

We must

learn

to profit from past mistakes, the use of outdated

regulations, poor scoring

systems.

Surfers must

take action to eliminate contests run under rules that

hinder favorable

acceptance of the sport by the general public.

Above all,

we

must keep in mind that blame for badly-run contests such as

Makaha should

not entirely be put upon shoulders of a small group of

officials or sponsors.

We, the

competitors,

share this blame because we let it happen, we were a part of

it - and a

lot of us probably will be part of it again unless it's

changed by us.

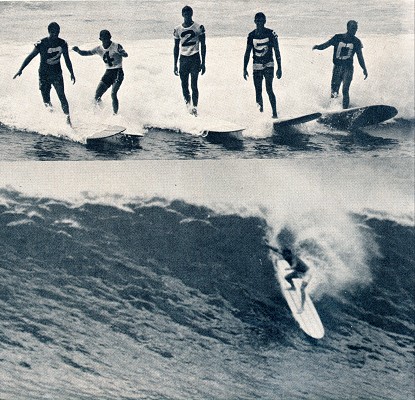

USSA 1966 RATINGS

The 1966

ratings

of the United States Surfing Association mark a milestone in

surfing competition

that probably means the end of contests dominated by just a

few top surfers.

For the

first

time, the USSA has segregated surfers into three categories-

AAA, AA and

A.

This is

similar

to international ski ratings and means that the top

competitors will battle

each other in contests, while lesser-rated surfers will

compete in separate

AA and A heats.

USSA

Competition

Chairman Hoppy Swarts pointed out that not all contests on

the circuit

this year will be segregated.

He said

there

will be a number of open contests where the three categories

will compete

together.

That is, the

AAA, AA and A surfers will be in the same heats.

But details

of

these open contests are still being worked out, Swarts said,

and will be

released later.

Under this

system,

surfers can move up - and also down - the competition

ladder.

For example,

Single A surfers can, by racking up contest points, move up

to AA and even

AAA ratings.

The same

holds

true for AA surfers.

Triple A

surfers

will, of course, have to defend their top position - or drop

back into

the AA or Single A division.

The placings

were computed on how surfers fared in contests in 1964 and

1965.

A two-year

spread

was used so that a top surfer would not lose his position

after merely

one bad contest year.

Here's the

list

for men, women and juniors.

Unfortunately,

space

doesn't permit running the Single A competitors in each

division

as the list runs into hundreds of names.

| MEN'S

TRIPLE

A

1. Rusty Miller 2. Skip Frye 3. Donald Takayama 4. Dewey Weber S. Corky Carroll 6. Rich Chew 7. Joey Cabell 8. Phil Edwards |

9. Steve Bigler 10. Mark Martinson 11. Robert August 12. Mike Doyle 13. Robert Kooken 14. John Peck 1 S. Bobby Patterson 16. Mickey Munoz |

WOMEN'S

TRIPLE

A

1. Joyce Hoffman 2. Joey Hamasaki 3. Nancy Nelson 4. Josette Lagardere 5. Dee Dee Arevalos 6. Margo Scotton 7. Linda Benson 8. Gail Yarbrough (Williams) |

Page 41

| JUNIORS

TRIPLE

A

1. David Nuuhiwa 2. Denny Tompkins 3. Pete Johnson 4. Herb Torrens 5. Mike Stevenson 6. Alf Laws 7. Herbie Fletcher 8. Dale Struble 9. Dru Harrison 10. Dickie Moon 11. Mike Purpus 12.. Bill Gray 13. Greg Tucker 14. Jim Irons 15. Bill Hamilton 16. Steve Schlickenmeyer |

OPEN

TANDEM

1. Mike Doyle 2. Pete Peterson 3. Don Hansen 4. Bob Moore 5. Jack Iverson 6. Mickey Munoz 7. Steve Boehne 8. Hobie Alter 9. Jim Graham 10. Joe Metzger 11. Rusty Miller 12. Corky Carroll 13. Nick Carollo 14. Sam Harwood |

|

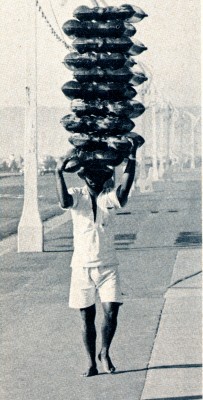

Left:

Page 61 Durban's not always crowded, however, and during April before the July crowds, it frequently looks like this as a native carrying stacked surf riders strolls down an almost deserted main street on the strand. Right:

Durban's beaches are segregated so this native youngster can't join these three surfers strolling along Dairy Beach near the West Street Groyne for a little fun in the surf. |

|

Half

believing

some of the more distorted "facts" on South Africa prevalent

in Australia,

I was completely unprepared for the friendliness and

courtesy received

from all sections of the community - whether Indian, Bantu

or white South

African.

Page 76

LOST

HOOD ORNAMENT DEPT.

Honolulu

police

are trying extra hard to crack the case of the missing

automobile hood

ornament.

Why?

Because the

11-inch,

5-pound statuette was taken from the car of Duke Kahanamoku.

The ornament

depicts Duke riding a surf- board.

A

hundred-dollar

reward, with no questions asked, has been posted for its

return.

The ornament

was torn from the hood of Duke's Lincoln Continental while

the car was

parked for just a few moments near the Edgewater Hotel at

Waikiki Beach.

The Duke,

who

had loaned his car to a friend, was in New York at the time

to appear on

the Ed Sullivan show and attend the opening of the Swimming

Hall of Fame

in Florida.

It's

especially

tragic because the ornament was hand-carved 30 years ago by

an artist now

dead.

There is no

existing

mold.

Commented

the

Duke: "You know, I place great sentimental value on that

statue, perhaps

more than on many of my other awards." Considering all the

baubles, trophies

and medals that Duke picked up as the Island's greatest

surfer, swimmer

and Olympic Champion - that's quite a statement.

The Duke

added:

"I'm sure no surfer or Island fellow took it, because no one

would do such

a thing."

|

Volume 7 Number 2 May 1966. Cover:

Copy

courtesy of

the Graham Sorensen Collection.

Rusty Miller and windy Sunset

Beach.

Page 27. |

|

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |