surftrdrarch.com.au

|

surfresearch.com.au

jack london : a royal sport,

1907-1911

|

Jack London : Riding the

South Sea Surf, 1907 - A Royal Sport, 1907.

London, Jack:

Riding the South Sea Surf

The Woman's Home Companion,

October 1907.

The Joys of the Surf-Rider, Pall

Mall, 1908.

A Royal Sport

The Cruise of the Snark.

Macmillan and Company, New York, 1911.

Project Gutenberg

http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/2512

Introduction

The renowned

novelist, Jack London, on his first visited Honolulu in

June1904, as benefiting his status, was taken for a canoe ride

at Waikiki.

At this point, in

a letter to his future wife, he merely noted that he had bathed

at Waikiki.

London was far

more impressed with surfing on his return three years later.

Jack London,

his wife Charmian, and crew sailed the yacht Snark into

the harbour at Honolulu sometime in late May 1907, a short

time after the arrival of professional journalist, Alexander

Hume Ford.

Ford was a

widely travelled who, like London, had previously

visited Hawaii.

On this visit

London was far more enthusiastic about surfing, Ford was

enthusiastic.

Their stays

were brief, but their impact was huge with both promoting

surfriding in widely circulated articles.

Central in

their writing was George Freeth, lauded as "probably the

most expert surf board rider in the world" and who "has

probably done more to revive the wonderful art of the

ancient Hawaiians here at home than any other one person."

London 's

landmark article, "Riding the South Sea Surf",

appeared in the October 1907 edition of the widely

circulated The Woman's Home Companion.

The article was

written in the first weeks of June, several months before

publication, and London's copy was probably already on its way

to the Home Companion editor before Freeth was

profiled by Ford in the Honolulu press at the end of the

month.

Although a

Honolulu paper announced the article's publication, and

printed excepts, on 7th October, the Snark had

reportedly left from Hilo on that same day and it is possible

that London did not see it in print until he returned to San

Francisco.

The article

was subsequently reprinted in England by Pall Mall

magazine the following year and excerpts appeared in daily

papers around the world.

In 1911 it was

included in a collection of London's writings from the Pacfic,

Voyage of the the Snark, under the chapter

heading "A Royal Sport", by which the article is now

commonly known.

Overview

The preface quotes from Mark Twain's account of

1872, London clearly implying that his essay examines the claim

that "none but natives ever master the art of surf-bathing

thoroughly."

While Twain's observation may have

been largely correct in 1872, since 1890 the number and

skills of haole surfers had steadily increased, and by

1907 the relative merits of native and

haole surfers was an ongoing discussion on the beach at

Waikiki.

London begins

"That is what it is, a royal sport for the natural kings of

the earth."

Here, "royal"

appears to imply "regal" or "stately", and the article does

not specically denote the role of the ancient Hawai'ian

royalty in surfing's heritage.

On the shores

of Waikiki, a scene dominated by the "majestic surf," he

observes a native Hawa'iian, a "Kanaka," who

rides a breaker for a quarter of a mile to the beach.

In a flamboyant

description, this surfboard rider is "a Mercury" who

has "mastered matter and the brutes and lorded it over

creation," more an Olympic god than an earthly king, a

role that London himself seeks to emulate.

The next

paragraphs detail a scientific explanation of the motion of

ocean waves and an explanation of the dynamics of surf riding.

The concept

that the water in an ocean wave does not move but rather is

the result of a circular motion, which when interrrupted

results in breaking surf, was probably enlightening to the

general reader, but the scientific community had been studying

this phenomena for a century

The first wave

theory was proposed by Franz

Gerstner of Czehoslovakia in 1802, followed by

experiments in Germany with the first wave tank by the Weber

brothers in 1825.

By 1867 wave

motion theory was noted in books about water sports, one such

work a likely source for London.

He also

describes waves of translation, broken waves where the water

does move shoreward, and the difficulties they pose to the

surfrider.

The analysis

of the dynamics of surfing is insightful in attempting to

describe the concept of triming, where the board's position

relative to the wave face appears both stationary and moving -

"you keep on sliding and you'll never reach the bottom."

He suggests

that board speed equals wave speed.

While this is a

necessary, or minimal, condition for successful wave riding,

London does not consider one of surfriding's exciting

attractions - that surfboards often travel faster than wave

speed.

In his first

attempts at prone surfing with a small board at Waikiki,

London unsuccessfully attempts to emulate a number of juvenile

natives, before taking instruction from Alexander Hume Ford.

A. H. Ford is a

recently arrived surfriding enthusiast, by implication "a

strong swimmer" who London credits with prodigious

atheletic ability.

In a matter of

weeks since arriving on Oahu and without the benefits of

instruction, Ford has mastered prone surfing and, after

purchasing a "man's sized" board, is now riding

standing and sharing waves on the outer reefs with George

Freeth.

In contrast, a

year later Ford would recall that he "learned the from the

small boys of Waikiki" and that it took "four

hours a day to the sport for nearly three months."

Furthermore,

one of the Snark crew, Martin Johnson, also tried his

"luck at surf-board riding" while on Oahu.

Johnson's

attempts were rudimentary, and he noted that surf riding "is

said to be one of the greatest sports in the world, but ...

it takes several months, at the least, really to learn it."

He echoed Mark

Twain's view, adding "Let me say here that it is my honest

belief that only the native Hawaiians ever really learn the

trick in all its intricacies," this, in an apparent

contradiction of Ford's assessment, "despite the fact

that, at several contests held, white men have come out

victorious."

Ford lends his

large board to London for a prone surfing lesson, and in half

an hour he is successfully catching waves and has advanced

to "leg-steering" to change the board's

direction, particularly useful in avoiding other bathers.

The next day

Ford takes London to the "blue water " of the outer

reefs where he is introduced to George Freeth and rides prone

on his "first big wave."

Evidently,

London had no difficulty in previously obtaining a small board

and Ford is, likewise, able to procure another suitable large

board for the second day's surfing.

While Freeth is

clearly experienced and willing to offer useful advice, London

does not otherwise directly assess his surfing skill.

.

London's

enthusiasm gets the better of him and four hours later he

returns to the beach with a severe case of sunburn.

Reports in the

Honolulu press suggest that this was in the first week of

June.

The article

concludes with London dictating from his bed and resolving to

ride standing, like Ford and Freeth, before leaving Hawai'i. .

|

Publication,

1907-1911.

Jack London's account of

surfboard riding was first published in The

Woman's Home Companion in October 1907.

Written from his bed on the

Waikik beachfront in early June 1906, it appeared in

print just as he was about to depart Hawai'i for the

South Seas.

Titled Riding the South

Sea Surf, the article was prefaced with a

quotation from Mark Twain from Roughing It (1872)

and the text was formatted with sub-headings.

An

edited version of the essay, with some introductory

comments and the omissions indicated, was published in

Honolulu by the Hawaiian Star in

October, 1907.

A

sub-title questioned whether London had achieved his

goal of riding upright before departing Waikiki.

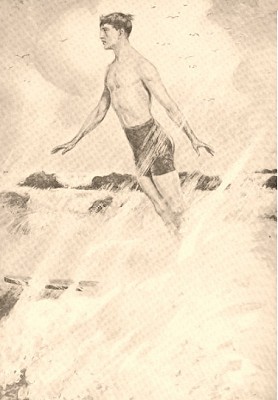

The second printing was in Pall

Mall in 1908, under the title The Joys

of the Surf-Rider, without the quotation from

Twain.

It had different sub-headings

and included an illustration by P.F.S. Spence.

Another

edited version, accredited to Pall Mall and

with its title, was printed in Brisbane by the Queenslander

in November 1908.

In 1911 it was reprinted as A

Royal Sport, a chapter in The Cruise of the Snark, a collection of essays

separately published between 1908 and 1910..

Here it had neither the quote

from Twain, the sub-headings, nor the illustration.

|

London,

Jack:

The Cruise of the Snark.

Macmillan

and Company,

New York, 1911

|

Patrick Moser also notes some minor

adjustments to the text, basically two instances of changing the

word "black;" once to to "brown" and once to "brown

and golden."

Moser: Pacific Passages

(2008), page 335.

There is, however, an additional paragraph in Chapter IV that

describes "a Kanaka on a surf-board,"

with similar imagery as the

full account in Chapter VI, see Aside,

below.

The Compound edition, below, reproduces

the quote from Mark Twain, the sub-headings in brackets: {Pall

Mall, 1908} and [Snark, 1911], and the

illustration.

The

Cruise of the Snark, 1911.

Introduction

The book tells

the story of the Snark's Pacific voyage, composed

largely from of a collection of essays, previously published in

a variety of periodicals.

A Royal Sport,

Chapter VI, was pubished in The Woman's

Home Companion (1907) and Pall Mall (1908),

see above.

The Lepers of

Molokai first appeared as articles in The Woman's

Home Companion(1908) and the Contemporary

Review (1909).

Other essays

possibly appeared in the Pacific Monthly and Harper's

Weekly.

London

takes inexperienced crew, including his wife, Charmain

across the Pacific, with visits to Hawai'i, the Solomon

Islands, Western Samoa, the Marquesas, and Tahiti.

Due to illness

(?), London abandoned the voyage and traveled from the

Solomons to Australia by steamer in November, 1908.

On his

recovery, the London's returned to California.

Overview

Establishing

the book's aquatic theme, the opening sentence is "It

began in the swimming pool at Glen Ellen."

Throughout

there

are numerous references to sea and swell condtions and several

descriptive passages of the beach at Waikiki.

As well as the dramatic account of

surfriding in Chapter VI, there is also a similarly enthusiastic

report of speed sailing in an outrigger canoe at Raiatea in

Chapter XII.

In several places, London's

narrative appears to be at odds with the recollections of

others; his visit to Molokai, his nautical skills, the role of

Charmian, and in the account of surfboard riding.

Whereas London

accredits A.H. Ford with mastering surfboard riding in a

matter of weeks and without the benefits of instruction, Ford

himself later wrote that he "learned from the small boys

of Waikiki" and that it took "four hours a day to

the sport for nearly three months."

Chapter VII, The

Lepers

of Molokai, was first published in the Woman's

Home Companion in early 1908; the introduction

noting that London had "risked his neck at surf-board

riding and forced his way into the forbidden district on

Molokai."

In a letter to

the Hawaiian Gazette in April, a correspondent

complained that "London did not force himself into the

settlement, as everyone here well knows, but went under

official escort, and as for the risk he took with his neck

at Waikiki, it is the same risk that every ten-year-old boy

in the Islands takes and enjoys."

London details

the difficulties of navigation in Chapter XIV, The Amateur

Navigator, and problems with the Snark's engines

in Chapter IX, A Pacific Traverse.

Joe Dunn, an

experienced boatswain, joined the crew for the voyage from

Honolulu to Hilo.

Interviewed in

San Francisco in late 1907, he recalled that "during the

trip everybody acted as navigator ... but most of the time

it was Mrs. London in bloomers."

Furthermore, he

considered the yacht's engines completely unsuitable, and

noted that there was "a gasoline engine to hoist the

anchor, (but) Dunn says that he could lift the

little anchor with one hand."

References

1872 Mark Twain : Roughing It.

1908 Jack London : Aloha Oe.

1908 Alexander Hume Ford : Riding

Breakers.

1908 Alexander Hume Ford : A Boy's

Paradise in the Pacific.

1913 Martin Johnson : Through

the South Seas with Jack London.

1917 Charmian London : Surfriding at Waikiki

1907-1917.

The Esoteric Curiosa: Knowledge

Is Power: The Joys of the Surf-Rider, Pall

Mall Magazine, 1908, pages.

Illustration: P.F.S. Spence: "A young god bronzed with sunburn."

http://theesotericcuriosa.blogspot.com.au/2012/09/surfing-royal-sport-as-described-by.html

wikikipedia

Jack London

Jack London Web Page

P.F. S.

Spence, (1868-1933)

Australia,

Fox, Frank.

painted by

Spence, P. F. S.,

London,

Black, 1910.

Legislative

Assembly, NSW Parliament House, Sydney.

Portrait of Sir

George Didds (Premier) by P.F. S. Spence, (1868-1933)

CHAPTER I — FOREWORD

It began in

the swimming pool at Glen Ellen.

Between

swims it was our wont to come out and lie in the sand and

let our skins breathe the warm air and soak in the sunshine.

Roscoe was a yachtsman.

I had

followed the sea a bit.

It was

inevitable that we should talk about boats.

We talked

about small boats, and the seaworthiness of small boats.

We instanced

Captain Slocum and his three years' voyage around the world

in the Spray.

We asserted

that we were not afraid to go around the world in a small

boat, say forty feet long.

We asserted

furthermore that we would like to do it.

We asserted

finally that there was nothing in this world we'd like

better than a chance to do it.

...

CHAPTER II — THE INCONCEIVABLE AND MONSTROUS

And in the

end we sailed away, on Tuesday morning, April 23, 1907.

We started

rather lame, I confess.

We had to

hoist anchor by hand, because the power transmission was a

wreck.

Also, what

remained of our seventy-horse-power engine was lashed down

for ballast on the bottom of the Snark.

But what of

such things?

They could

be fixed in Honolulu, and in the meantime think of the

magnificent rest of the boat!

It is true,

the engine in the launch wouldn't run, and the life-boat

leaked like a sieve; but then they weren't the Snark;

they were mere appurtenances.

The things

that counted were the water-tight bulkheads, the solid

planking without butts, the bath- room devices—they were the

Snark.

And then

there was, greatest of all, that noble, wind-punching bow.

We sailed

out through the Golden Gate and set our course south toward

that part of the Pacific where we could hope to pick up with

the north-east trades.

CHAPTER IV — FINDING ONE'S WAY ABOUT

...

So the Snark started on her long voyage without a navigator.

We beat

through the Golden Gate on April 23, and headed for the

Hawaiian Islands, twenty-one hundred sea-miles away as the

gull flies.

And the

outcome was our justification.

We arrived.

And we

arrived, furthermore, without any trouble, as you shall see;

that is, without any trouble to amount to anything.

...

As I write these

lines I lift my eyes and look seaward.

I am on the

beach of Waikiki on the island of Oahu.

Far, in the

azure sky, the trade-wind clouds drift low over the blue-green

turquoise of the deep sea.

Nearer, the

sea is emerald and light olive-green.

Then comes the

reef, where the water is all slaty purple flecked with red.

Still nearer

are brighter greens and tans, lying in alternate stripes and

showing where sandbeds lie between the living coral banks.

Through and over and out of these wonderful colours tumbles

and thunders a magnificent surf.

As I say, I

lift my eyes to all this, and through the white crest of a

breaker suddenly appears a dark figure, erect, a man-fish or a

sea-god, on the very forward face of the crest where the top

falls over and down, driving in toward shore, buried to his

loins in smoking spray, caught up by the sea and flung

landward, bodily, a quarter of a mile.

It is a Kanaka

on a surf-board.

And I know

that when I have finished these lines I shall be out in that

riot of colour and pounding surf, trying to bit those breakers

even as he, and failing as he never failed, but living life as

the best of us may live it.

And the

picture of that coloured sea and that flying sea-god Kanaka

becomes another reason for the young man to go west, and

farther west, beyond the Baths of Sunset, and still west till

he arrives home again.

...

And we learned

well, better than for a while we thought we had.

At the

beginning of the second dog-watch one evening, Charmian and I

sat down on the forecastle-head for a rubber of cribbage.

Chancing to glance ahead, I saw cloud-capped mountains rising

from the sea.

We were

rejoiced at the sight of land, but I was in despair over our

navigation.

I thought we

had learned something, yet our position at noon, plus what we

had run since, did not put us within a hundred miles of land.

But there was

the land, fading away before our eyes in the fires of sunset.

The land was

all right.

There was no

disputing it.

Therefore our

navigation was all wrong.

But it wasn't.

That land we

saw was the summit of Haleakala, the House of the Sun, the

greatest extinct volcano in the world. It towered ten thousand

feet above the sea, and it was all of a hundred miles away.

We sailed all

night at a seven-knot clip, and in the morning the House of

the Sun was still before us, and it took a few more hours of

sailing to bring it abreast of us.

"That island

is Maui," we said, verifying by the chart.

"That next

island sticking out is Molokai, where the lepers are.

And the island

next to that is Oahu.

There is

Makapuu Head now.

We'll be in

Honolulu to-morrow.

Our navigation

is all right."

CHAPTER V — THE FIRST LANDFALL

Twenty-seven

days out from San Francisco we arrived at the island of

Oahu, Territory of Hawaii.

In the early

morning we drifted around Diamond Head into full view of

Honolulu; and then the ocean burst suddenly into life.

Flying fish

cleaved the air in glittering squadrons.

In five

minutes we saw more of them than during the whole voyage.

Other fish,

large ones, of various sorts, leaped into the air.

There was

life everywhere, on sea and shore.

We could see

the masts and funnels of the shipping in the harbour, the

hotels and bathers along the beach at Waikiki, the smoke

rising from the dwelling-houses high up on the volcanic

slopes of the Punch Bowl and Tantalus.

The

custom-house tug was racing toward us and a big school of

porpoises got under our bow and began cutting the most

ridiculous capers.

The port

doctor's launch came charging out at us, and a big sea

turtle broke the surface with his back and took a look at

us.

Never was

there such a burgeoning of life.

Strange

faces were on our decks, strange voices were speaking, and

copies of that very morning's newspaper, with cable reports

from all the world, were thrust before our eyes.

Incidentally,

we

read that the Snark and all hands had been lost at

sea, and that she had been a very unseaworthy craft anyway.

And while we read this information a wireless message was

being received by the congressional party on the summit of

Haleakala announcing the safe arrival of the Snark.

...

It was the

Snark's first landfall—and such a landfall!

For twenty-

seven days we had been on the deserted deep, and it was

pretty hard to realize that there was so much life in the

world.

We were made

dizzy by it.

We could not

take it all in at once.

We were like

awakened Rip Van Winkles, and it seemed to us that we were

dreaming.

On one side

the azure sea lapped across the horizon into the azure sky;

on the other side the sea lifted itself into great breakers

of emerald that fell in a snowy smother upon a white coral

beach.

Beyond the

beach, green plantations of sugar-cane undulated gently

upward to steeper slopes, which, in turn, became jagged

volcanic crests, drenched with tropic showers and capped by

stupendous masses of trade-wind clouds.

At any rate,

it was a most beautiful dream.

The Snark

turned and headed directly in toward the emerald surf, till

it lifted and thundered on either hand; and on either hand,

scarce a biscuit-toss away, the reef showed its long teeth,

pale green and menacing.

Abruptly

the land itself, in a riot of olive-greens of a thousand

hues, reached out its arms and folded the Snark in.

There was no

perilous passage through the reef, no emerald surf and azure

sea— nothing but a warm soft land, a motionless lagoon, and

tiny beaches on which swam dark-skinned tropic children.

The sea had

disappeared.

The Snark's

anchor

rumbled the chain through the hawse-pipe, and we lay without

movement on a "lineless, level floor."

It was all

so beautiful and strange that we could not accept it as

real.

On the chart

this place was called Pearl Harbour, but we called it Dream

Harbour.

CHAPTER VI — A ROYAL SPORT

Riding the South Sea

Surf, 1907.

The Joys of the Surf-Rider - How I

Mastered a Splendid Sport, 1908.

This

transcription compounds the first three editions of the

article:

1. Riding the South

Sea Surf, Woman's Home Companion, 1907.

Only this edition had the preface by Mark Twain from

Roughing

It (1872), reproduced below.

The sub-headings

only appear, and vary, in the the magazine editions,

here indicated as (1907)

2. The

Joys of the Surf-Rider - How I Mastered a Splendid

Sport, Pall

Mall, 1908.

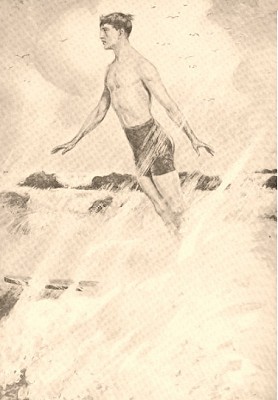

The illustration by P.F.S.

Spence only

appeared in this edition, its sub-headings

indicated as (1908)

3.

A Royal Sport, The Cruise of the Snark, 1911.

The

two adjustments in the text of the 1911 edition, noted by Patrick Moser (2008), are enclosed

in [brackests].

|

P.F.S.

Spence :

A

young god bronzed with sunburn.

|

CHAPTER VI — A ROYAL SPORT, 1911.

Riding

the South Sea Surf, 1907.

The Joys of the Surf-Rider - How I Mastered a

Splendid Sport, 1908.

I tried

surf-bathing once, subsequently, but made a failure of

it.

I got the board placed right,

and at the right moment, too; but missed the connection

myself.

—The board struck the shore in

three quarters of a second, without any

cargo, and I struck the bottom about the same time,

with a couple of barrels of water in me.

None but natives ever master

the art of surf-bathing thoroughly.

That is what it

is, a royal sport for the natural kings of earth.

The grass

grows right down to the water at Waikiki Beach, and within

fifty feet of the everlasting sea.

The trees

also grow down to the salty edge of things, and one sits in

their shade and looks seaward at a majestic surf thundering

in on the beach to one's very feet.

Half a mile

out, where is the reef, the white-headed combers thrust

suddenly skyward out of the placid turquoise-blue and come

rolling in to shore.

One after

another they come, a mile long, with smoking crests, the

white battalions of the infinite army of the sea.

And one sits

and listens to the perpetual roar, and watches the unending

procession, and feels tiny and fragile before this

tremendous force expressing itself in fury and foam and

sound.

Indeed, one

feels microscopically small, and the thought that one may

wrestle with this sea raises in one's imagination a thrill

of apprehension, almost of fear.

Flying Through Air (1908)

Why, they

are a mile long, these bull-mouthed monsters, and they weigh

a thousand tons, and they charge in to shore faster than a

man can run.

What chance?

No chance at

all, is the verdict of the shrinking ego; and one sits, and

looks, and listens, and thinks the grass and the shade are a

pretty good place in which to be.

A Master of the Bull-Mouthed Breaker (1907)

And

suddenly, out there where a big smoker lifts skyward, rising

like a sea-god from out of the welter of spume and churning

white, on the giddy, toppling, overhanging and downfalling,

precarious crest appears the dark head of a man.

Swiftly he

rises through the rushing white.

His black

shoulders, his chest, his loins, his limbs—all is abruptly

projected on one's vision.

Where but

the moment before was only the wide desolation and

invincible roar, is now a man, erect, full-statured, not

struggling frantically in that wild movement, not buried and

crushed and buffeted by those mighty monsters, but standing

above them all, calm and superb, poised on the giddy summit,

his feet buried in the churning foam, the salt smoke rising

to his knees, and all the rest of him in the free air and

flashing sunlight, and he is flying through the air, flying

forward, flying fast as the surge on which he stands.

He is a

Mercury— a black [brown] Mercury.

His heels

are winged, and in them is the swiftness of the sea.

In truth,

from out of the sea he has leaped upon the back of the sea,

and he is riding the sea that roars and bellows and cannot

shake him from its back.

But no

frantic outreaching and balancing is his.

He is

impassive, motionless as a statue carved suddenly by some

miracle out of the sea's depth from which he rose.

And straight

on toward shore he flies on his winged heels and the white

crest of the breaker.

There is a

wild burst of foam, a long tumultuous rushing sound as the

breaker falls futile and spent on the beach at your feet;

and there, at your feet steps calmly ashore a Kanaka, burnt

[black] golden and brown by the tropic sun.

Several

minutes ago he was a speck a quarter of a mile away.

He has

"bitted the bull-mouthed breaker" and ridden it in, and the

pride in the feat shows in the carriage of his magnificent

body as he glances for a moment carelessly at you who sit in

the shade of the shore.

He is a

Kanaka—and more, he is a man, a member of the kingly species

that has mastered matter and the brutes and lorded it over

creation.

How I Came to Tackle

Surf Riding (1907)

And one

sits and thinks of Tristram's last wrestle with the sea on

that fatal morning; and one thinks further, to the fact that

that Kanaka has done what Tristram never did, and that he

knows a joy of the sea that Tristram never knew.

And still

further one thinks.

It is all

very well, sitting here in cool shade of the beach, but you

are a man, one of the kingly species, and what that Kanaka

can do, you can do yourself.

Go to.

Strip off

your clothes that are a nuisance in this mellow clime.

Get in and

wrestle with the sea; wing your heels with the skill and

power that reside in you; bit the sea's breakers, master

them, and ride upon their backs as a king should.

What Is A Wave? (1908)

And that is

how it came about that I tackled surf-riding.

And now that

I have tackled it, more than ever do I hold it to be a royal

sport. But first let me explain the physics of it. A wave is

a communicated agitation.

The water that composes the body of a wave does not move. If

it did, when a stone is thrown into a pond and the ripples

spread away in an ever widening circle, there would appear

at the centre an ever increasing hole.

No, the water that composes the body of a wave is

stationary.

Thus, you may watch a particular portion of the ocean's

surface and you will see the sane water rise and fall a

thousand times to the agitation communicated by a thousand

successive waves.

Now imagine this communicated agitation moving shoreward.

As the bottom shoals, the lower portion of the wave strikes

land first and is stopped.

But water is fluid, and the upper portion has not struck

anything, wherefore it keeps on communicating its agitation,

keeps on going. And when the top of the wave keeps on going,

while the bottom of it lags behind, something is bound to

happen.

The bottom of the wave drops out from under and the top of

the wave falls over, forward, and down, curling and cresting

and roaring as it does so.

It is the bottom of a wave striking against the top of the

land that is the cause of all surfs.

But the

transformation from a smooth undulation to a breaker is not

abrupt except where the bottom shoals abruptly.

Say the bottom shoals gradually for from quarter of a mile

to a mile, then an equal distance will be occupied by the

transformation.

Such a bottom is that off the beach of Waikiki, and it

produces a splendid surf- riding surf.

One leaps upon the back of a breaker just as it begins to

break, and stays on it as it continues to break all the way

in to shore.

Just what Surf Riding Means (1907)

- A Simple Outfit (1908)

And now to

the particular physics of surf-riding.

Get out on a flat board, six feet long, two feet wide, and

roughly oval in shape.

Lie down upon it like a small boy on a coaster and paddle

with your hands out to deep water, where the waves begin to

crest. Lie out there quietly on the board.

Sea after sea breaks before, behind, and under and over you,

and rushes in to shore, leaving you behind.

When a wave crests, it gets steeper. Imagine yourself, on

your hoard, on the face of that steep slope.

If it stood still, you would slide down just as a boy slides

down a hill on his coaster.

"But," you object, "the wave doesn't stand still."

Very true, but the water composing the wave stands still,

and there you have the secret.

If ever you start sliding down the face of that wave, you'll

keep on sliding and you'll never reach the bottom.

Please don't laugh.

The face of that wave may be only six feet, yet you can

slide down it a quarter of a mile, or half a mile, and not

reach the bottom. For, see, since a wave is only a

communicated agitation or impetus, and since the water that

composes a wave is changing every instant, new water is

rising into the wave as fast as the wave travels.

You slide down this new water, and yet remain in your old

position on the wave, sliding down the still newer water

that is rising and forming the wave.

You slide precisely as fast as the wave travels.

If it travels fifteen miles an hour, you slide fifteen miles

an hour.

Between you and shore stretches a quarter of mile of water.

As the wave travels, this water obligingly heaps itself into

the wave, gravity does the rest, and down you go, sliding

the whole length of it.

If you still cherish the notion, while sliding, that the

water is moving with you, thrust your arms into it and

attempt to paddle; you will find that you have to be

remarkably quick to get a stroke, for that water is dropping

astern just as fast as you are rushing ahead.

Blows From A Breaker (1908)

And now for

another phase of the physics of surf-riding.

All rules have their exceptions.

It is true that the water in a wave does not travel forward.

But there is what may be called the send of the sea.

The water in the overtoppling crest does move forward, as you

will speedily realize if you are slapped in the face by it, or

if you are caught under it and are pounded by one mighty blow

down under the surface panting and gasping for half a minute.

The water in the top of a wave rests upon the water in the

bottom of the wave.

But when the bottom of the wave strikes the land, it stops,

while the top goes on. It no longer has the bottom of the wave

to hold it up.

Where was solid water beneath it, is now air, and for the

first time it feels the grip of gravity, and down it falls, at

the same time being torn asunder from the lagging bottom of

the wave and flung forward.

And it is because of this that riding a surf-board is

something more than a mere placid sliding down a hill. In

truth, one is caught up and hurled shoreward as by some

Titan's hand.

My Ignominious Failure (1907)

I deserted

the cool shade, put on a swimming suit, and got hold of a

surf-board. It was too small a board.

But I didn't know, and nobody told me. I joined some little

Kanaka boys in shallow water, where the breakers were well

spent and small—a regular kindergarten school.

I watched the little Kanaka boys.

When a likely-looking breaker came along, they flopped upon

their stomachs on their boards, kicked like mad with their

feet, and rode the breaker in to the beach.

I tried to emulate them.

I watched them, tried to do everything that they did, and

failed utterly.

The breaker swept past, and I was not on it.

I tried again and again.

I kicked twice as madly as they did, and failed.

Half a dozen would be around.

We would all leap on our boards in front of a good breaker.

Away our feet would churn like the stern-wheels of river

steamboats, and away the little rascals would scoot while I

remained in disgrace behind.

Lessons From An Expert (1908)

I tried for

a solid hour, and not one wave could I persuade to boost me

shoreward.

And then arrived a friend, Alexander Hume Ford, a globe

trotter by profession, bent ever on the pursuit of

sensation.

And he had found it at Waikiki.

Heading for Australia, he had stopped off for a week to find

out if there were any thrills in surf-riding, and he had

become wedded to it.

He had been at it every day for a month and could not yet

see any symptoms of the fascination lessening on him.

He spoke with authority.

"Get off

that board," he said.

"Chuck it away at once.

Look at the way you're trying to ride it.

If ever the nose of that board hits bottom, you'll be

disembowelled.

Here, take my board.

It's a man's size."

I am always

humble when confronted by knowledge.

Ford knew.

He showed me how properly to mount his board.

Then he waited for a good breaker, gave me a shove at the

right moment, and started me in.

Ah, delicious moment when I felt that breaker grip and fling

me.

On I

dashed, a hundred and fifty feet, and subsided with the

breaker on the sand.

From that moment I was lost.

I waded back to Ford with his board.

It was a large one, several inches thick, and weighed all of

seventy-five pounds.

He gave me advice, much of it.

He had had no one to teach him, and all that he had

laboriously learned in several weeks he communicated to me

in half an hour.

I really learned by proxy.

And inside of half an hour I was able to start myself and

ride in.

I did it time after time, and Ford applauded and advised.

For instance, he told me to get just so far forward on the

board and no farther.

But I must have got some farther, for as I came charging in

to land, that miserable board poked its nose down to bottom,

stopped abruptly, and turned a somersault, at the same time

violently severing our relations.

I was tossed through the air like a chip and buried

ignominiously under the downfalling breaker.

And I realized that if it hadn't been for Ford, I'd have

been disembowelled.

That particular risk is part of the sport, Ford says.

Maybe he'll have it happen to him before he leaves Waikiki,

and then, I feel confident, his yearning for sensation will

be satisfied for a time.

I Save a Life (1907) -

A Life In Danger (1908)

When all is

said and done, it is my steadfast belief that homicide is

worse than suicide, especially if, in the former case, it is

a woman.

Ford saved me from being a homicide.

"Imagine your legs are a rudder," he said.

"Hold them close together, and steer with them."

A few minutes later I came charging in on a comber.

As I neared the beach, there, in the water, up to her waist,

dead in front of me, appeared a woman.

How was I to stop that comber on whose back I was?

It looked like a dead woman.

The board weighed seventy-five pounds, I weighed a hundred

and sixty-five.

The added weight had a velocity of fifteen miles per hour.

The board and I constituted a projectile.

I leave it to the physicists to figure out the force of the

impact upon that poor, tender woman.

And then I remembered my guardian angel, Ford.

"Steer with your legs!" rang through my brain.

I steered with my legs, I steered sharply, abruptly, with

all my legs and with all my might.

The board sheered around broadside on the crest.

Many things happened simultaneously.

The wave gave me a passing buffet, a light tap as the taps

of waves go, but a tap sufficient to knock me off the board

and smash me down through the rushing water to bottom, with

which I came in violent collision and upon which I was

rolled over and over.

I got my head out for a breath of air and then gained my

feet.

There stood the woman before me.

I felt like a hero.

I had saved her life.

And she laughed at me.

It was not hysteria.

She had never dreamed of her danger.

Anyway, I solaced myself, it was not I but Ford that saved

her, and I didn't have to feel like a hero.

And besides, that leg-steering was great.

In a few minutes more of practice I was able to thread my

way in and out past several bathers and to remain on top my

breaker instead of going under it.

"To-morrow,"

Ford said, "I am going to take you out into the blue water."

I looked

seaward where he pointed, and saw the great smoking combers

that made the breakers I had been riding look like ripples.

I don't know what I might have said had I not recollected

just then that I was one of a kingly species.

So all that I did say was, "All right, I'll tackle them

to-morrow."

The Wonderful Hawaiian Water (1907)

The water

that rolls in on Waikiki Beach is just the same as the water

that laves the shores of all the Hawaiian Islands; and in

ways, especially from the swimmer's standpoint, it is

wonderful water.

It is cool enough to be comfortable, while it is warm enough

to permit a swimmer to stay in all day without experiencing

a chill. Under the sun or the stars, at high noon or at

midnight, in midwinter or in midsummer, it does not matter

when, it is always the same temperature—not too warm, not

too cold, just right. It is wonderful water, salt as old

ocean itself, pure and crystal-clear. When the nature of the

water is considered, it is not so remarkable after all that

the Kanakas are one of the most expert of swimming races.

Triumph At Last (1908)

So it was,

next morning, when Ford came along, that I plunged into the

wonderful water for a swim of indeterminate length. Astride

of our surf-boards, or, rather, flat down upon them on our

stomachs, we paddled out through the kindergarten where the

little Kanaka boys were at play.

Soon we were out in deep water where the big smokers came

roaring in.

The mere struggle with them, facing them and paddling

seaward over them and through them, was sport enough in

itself.

One had to have his wits about him, for it was a battle in

which mighty blows were struck, on one side, and in which

cunning was used on the other side—a struggle between

insensate force and intelligence.

I soon learned a bit.

When a breaker curled over my head, for a swift instant I

could see the light of day through its emerald body; then

down would go my head, and I would clutch the board with all

my strength.

Then would come the blow, and to the onlooker on shore I

would be blotted out.

In reality the board and I have passed through the crest and

emerged in the respite of the other side.

I should not recommend those smashing blows to an invalid or

delicate person.

There is weight behind them, and the impact of the driven

water is like a sandblast.

Sometimes one passes through half a dozen combers in quick

succession, and it is just about that time that he is liable

to discover new merits in the stable land and new reasons

for being on shore.

Out there

in the midst of such a succession of big smoky ones, a third

man was added to our party, one Freeth.

Shaking the water from my eyes as I emerged from one wave

and peered ahead to see what the next one looked like, I saw

him tearing in on the back of it, standing upright on his

board, carelessly poised, a young god bronzed with sunburn.

We went through the wave on the back of which he rode.

Ford called to him.

He turned an airspring from his wave, rescued his board from

its maw, paddled over to us and joined Ford in showing me

things. One thing in particular I learned from Freeth,

namely, how to encounter the occasional breaker of

exceptional size that rolled in. Such breakers were really

ferocious, and it was unsafe to meet them on top of the

board.

But Freeth showed me, so that whenever I saw one of that

calibre rolling down on me, I slid off the rear end of the

board and dropped down beneath the surface, my arms over my

head and holding the board.

Thus, if the wave ripped the board out of my hands and tried

to strike me with it (a common trick of such waves), there

would be a cushion of water a foot or more in depth, between

my head and the blow.

When the wave passed, I climbed upon the board and paddled

on.

Many men have been terribly injured, I learn, by being

struck by their boards.

The Trick is "Non-Resistance" (1908) - The

Secret:

Non-Resistance (1908)

The whole

method of surf-riding and surf-fighting, learned, is one of

non-resistance.

Dodge the blow that is struck at you.

Dive through the wave that is trying to slap you in the face.

Sink down, feet first, deep under the surface, and let the big

smoker that is trying to smash you go by far overhead.

Never be rigid.

Relax.

Yield yourself to the waters that are ripping and tearing at

you.

When the undertow catches you and drags you seaward along the

bottom, don't struggle against it.

If you do, you are liable to be drowned, for it is stronger

than you.

Yield yourself to that undertow.

Swim with it, not against it, and you will find the pressure

removed.

And, swimming with it, fooling it so that it does not hold

you, swim upward at the same time.

It will be no trouble at all to reach the surface.

The man who

wants to learn surf-riding must be a strong swimmer, and he

must be used to going under the water.

After that, fair strength and common-sense are all that is

required.

The force of the big comber is rather unexpected.

There are mix-ups in which board and rider are torn apart

and separated by several hundred feet.

The surf-rider must take care of himself.

No matter how many riders swim out with him, he cannot

depend upon any of them for aid.

The fancied security I had in the presence of Ford and

Freeth made me forget that it was my first swim out in deep

water among the big ones.

I recollected, however, and rather suddenly, for a big wave

came in, and away went the two men on its back all the way

to shore.

I could have been drowned a dozen different ways before they

got back to me.

The Penalties Of Sunburn (1908)

One slides

down the face of a breaker on his surf-board, but he has to

get started to sliding. Board and rider must be moving

shoreward at a good rate before the wave overtakes them.

When you see the wave coming that you want to ride in, you

turn tail to it and paddle shoreward with all your strength,

using what is called the windmill stroke. This is a sort of

spurt performed immediately in front of the wave. If the

board is going fast enough, the wave accelerates it, and the

board begins its quarter-of-a-mile slide.

A Gleam of Success - and the Price (1907)

I shall

never forget the first big wave I caught out there in the

deep water.

I saw it coming, turned my back on it and paddled for dear

life.

Faster and faster my board went, till it seemed my arms

would drop off.

What was happening behind me I could not tell.

One cannot look behind and paddle the windmill stroke.

I heard the crest of the wave hissing and churning, and then

my board was lifted and flung forward.

I scarcely knew what happened the first half- minute.

Though I kept my eyes open, I could not see anything, for I

was buried in the rushing white of the crest.

But I did not mind.

I was chiefly conscious of ecstatic bliss at having caught

the wave.

At the end, of the half-minute, however, I began to see

things, and to breathe.

I saw that three feet of the nose of my board was clear out

of water and riding on the air.

I shifted my weight forward, and made the nose come down.

Then I lay, quite at rest in the midst of the wild movement,

and watched the shore and the bathers on the beach grow

distinct.

I didn't cover quite a quarter of a mile on that wave,

because, to prevent the board from diving, I shifted my

weight back, but shifted it too far and fell down the rear

slope of the wave.

It was my

second day at surf-riding, and I was quite proud of myself.

I stayed out there four hours, and when it was over, I was

resolved that on the morrow I'd come in standing up.

But that resolution paved a distant place.

On the morrow I was in bed.

I was not sick, but I was very unhappy, and I was in bed.

When describing the wonderful water of Hawaii I forgot to

describe the wonderful sun of Hawaii.

It is a tropic sun, and, furthermore, in the first part of

June, it is an overhead sun.

It is also an insidious, deceitful sun.

For the first time in my life I was sunburned unawares.

My arms, shoulders, and back had been burned many times in

the past and were tough; but not so my legs.

And for four hours I had exposed the tender backs of my

legs, at right- angles, to that perpendicular Hawaiian sun.

It was not until after I got ashore that I discovered the

sun had touched me.

Sunburn at first is merely warm; after that it grows intense

and the blisters come out.

Also, the joints, where the skin wrinkles, refuse to bend.

That is why I spent the next day in bed.

I couldn't walk.

And that is why, to-day, I am writing this in bed.

It is easier to than not to.

But to-morrow, ah, to-morrow, I shall be out in that

wonderful water, and I shall come in standing up, even as

Ford and Freeth. And if I fail to-morrow, I shall do it the

next day, or the next.

Upon one thing I am resolved: the Snark shall not

sail from Honolulu until I, too, wing my heels with the

swiftness of the sea, and become a sun-burned, skin-peeling

Mercury.

CHAPTER VII—THE LEPERS OF

MOLOKAI

CHAPTER VIII—THE HOUSE OF

THE SUN

CHAPTER IX—A PACIFIC TRAVERSE

Sandwich

Islands to Tahiti.—There is great difficulty in making this

passage across the trades. The whalers and all others speak

with great doubt of fetching Tahiti from the Sandwich

islands. Capt. Bruce says that a vessel should keep to the

northward until she gets a start of wind before bearing for

her destination. In his passage between them in November,

1837, he had no variables near the line in coming south, and

never could make easting on either tack, though he

endeavoured by every means to do so.

...

We sailed

from Hilo, Hawaii, on October 7, and arrived at Nuka-hiva,

in the Marquesas, on December 6. The distance was two

thousand miles as the crow flies, while we actually

travelled at least four thousand miles to accomplish it,

thus proving for once and for ever that the shortest

distance between two points is not always a straight line.

Had we headed directly for the Marquesas, we might have

travelled five or six thousand miles.

...

I have

forgotten to mention that the seventy-horse-power gasolene

engine, as usual, was not working, and that we could depend

upon wind alone. Neither was the launch engine working. And

while I am about it, I may as well confess that the

five-horse-power, which ran the lights, fans, and pumps, was

also on the sick-list. A striking title for a book haunts

me, waking and sleeping. I should like to write that book

some day and to call it "Around the World with Three

Gasolene Engines and a Wife." But I am afraid I shall not

write it, for fear of hurting the feelings of some of the

young gentlemen of San Francisco, Honolulu, and Hilo, who

learned their trades at the expense of the Snark's engines.

...

Then there

was the fishing. One did not have to go in search of it, for

it was there at the rail. A three-inch steel hook, on the

end of a stout line, with a piece of white rag for bait, was

all that was necessary to catch bonitas weighing from ten to

twenty-five pounds. Bonitas feed on flying-fish, wherefore

they are unaccustomed to nibbling at the hook. They strike

as gamely as the gamest fish in the sea, and their first run

is something that no man who has ever caught them will

forget. Also, bonitas are the veriest cannibals. The instant

one is hooked he is attacked by his fellows. Often and often

we hauled them on board with fresh, clean-bitten holes in

them the size of teacups.

...

But it is

the dolphin that is the king of deep-sea fishes. Never is

his colour twice quite the same. Swimming in the sea, an

ethereal creature of palest azure, he displays in that one

guise a miracle of colour. But it is nothing compared with

the displays of which he is capable. At one time he will

appear green—pale green, deep green, phosphorescent green;

at another time blue—deep blue, electric blue, all the

spectrum of blue. Catch him on a hook, and he turns to gold,

yellow gold, all gold. Haul him on deck, and he excels the

spectrum, passing through inconceivable shades of blues,

greens, and yellows, and then, suddenly, turning a ghostly

white, in the midst of which are bright blue spots, and you

suddenly discover that he is speckled like a trout. Then

back from white he goes, through all the range of colours,

finally turning to a mother-of-pearl.

For those

who are devoted to fishing, I can recommend no finer sport

than catching dolphin.

...

The

dolphins, which remained with us over a month, deserted us

north of the line, and not one was seen during the remainder

of the traverse.

...

We made our

easting, worked down through the doldrums, and caught a

fresh breeze out of south-by-west. Hauled up by the wind, on

such a slant, we would fetch past the Marquesas far away to

the westward. But the next day, on Tuesday, November 26, in

the thick of a heavy squall, the wind shifted suddenly to

the southeast. It was the trade at last. There were no more

squalls, naught but fine weather, a fair wind, and a

whirling log, with sheets slacked off and with spinnaker and

mainsail swaying and bellying on either side. The trade

backed more and more, until it blew out of the northeast,

while we steered a steady course to the southwest. Ten days

of this, and on the morning of December 6, at five o'clock,

we sighted land "just where it ought to have been," dead

ahead. We passed to leeward of Ua-huka, skirted the southern

edge of Nuka-hiva, and that night, in driving squalls and

inky darkness, fought our way in to an anchorage in the

narrow bay of Taiohae. The anchor rumbled down to the

blatting of wild goats on the cliffs, and the air we

breathed was heavy with the perfume of flowers. The traverse

was accomplished. Sixty days from land to land, across a

lonely sea above whose horizons never rise the straining

sails of ships.

CHAPTER X—TYPEE

To the

eastward Ua-huka was being blotted out by an evening rain-

squall that was fast overtaking the Snark. But that little

craft, her big spinnaker filled by the southeast trade, was

making a good race of it. Cape Martin, the southeasternmost

point of Nuku-hiva, was abeam, and Comptroller Bay was

opening up as we fled past its wide entrance, where Sail

Rock, for all the world like the spritsail of a Columbia

River salmon-boat, was making brave weather of it in the

smashing southeast swell.

...

But we were

more interested in the recesses of Comptroller Bay, where

our eyes eagerly sought out the three bights of land and

centred on the midmost one, where the gathering twilight

showed the dim walls of a valley extending inland. How often

we had pored over the chart and centred always on that

midmost bight and on the valley it opened—the Valley of

Typee. "Taipi" the chart spelled it, and spelled it

correctly, but I prefer "Typee," and I shall always spell it

"Typee." When I was a little boy, I read a book spelled in

that manner—Herman Melville's "Typee"; and many long hours I

dreamed over its pages. Nor was it all dreaming. I resolved

there and then, mightily, come what would, that when I had

gained strength and years, I, too, would voyage to Typee.

...

Abruptly,

with a roar of sound, Sentinel Rock loomed through the rain

dead ahead. We altered our course, and, with mainsail and

spinnaker bellying to the squall, drove past. Under the lea

of the rock the wind dropped us, and we rolled in an

absolute calm. Then a puff of air struck us, right in our

teeth, out of Taiohae Bay. It was in spinnaker, up mizzen,

all sheets by the wind, and we were moving slowly ahead,

heaving the lead and straining our eyes for the fixed red

light on the ruined fort that would give us our bearings to

anchorage. The air was light and baffling, now east, now

west, now north, now south; while from either hand came the

roar of unseen breakers. From the looming cliffs arose the

blatting of wild goats, and overhead the first stars were

peeping mistily through the ragged train of the passing

squall. At the end of two hours, having come a mile into the

bay, we dropped anchor in eleven fathoms. And so we came to

Taiohae.

In the

morning we awoke in fairyland. The Snark rested in a placid

harbour that nestled in a vast amphitheatre, the towering,

vine-clad walls of which seemed to rise directly from the

water. Far up, to the east, we glimpsed the thin line of a

trail, visible in one place, where it scoured across the

face of the wall.

...

Of all

inhabitants of the South Seas, the Marquesans were adjudged

the strongest and the most beautiful. Melville said of them:

"I was especially struck by the physical strength and beauty

they displayed . . . In beauty of form they surpassed

anything I had ever seen. Not a single instance of natural

deformity was observable in all the throng attending the

revels. Every individual appeared free from those blemishes

which sometimes mar the effect of an otherwise perfect form.

But their physical excellence did not merely consist in an

exemption from these evils; nearly every individual of the

number might have been taken for a sculptor's model."

Mendana, the discoverer of the Marquesas, described the

natives as wondrously beautiful to behold. Figueroa, the

chronicler of his voyage, said of them: "In complexion they

were nearly white; of good stature and finely formed."

Captain Cook called the Marquesans the most splendid

islanders in the South Seas. The men were described, as "in

almost every instance of lofty stature, scarcely ever less

than six feet in height."

...

CHAPTER XI—THE NATURE MAN

...

The years

passed, and, one sunny morning, the Snark poked her nose into

a narrow opening in a reef that smoked with the crashing

impact of the trade-wind swell, and beat slowly up Papeete

harbour. Coming off to us was a boat, flying a yellow flag. We

knew it contained the port doctor. But quite a distance off,

in its wake, was a tiny out rigger canoe that puzzled us. It

was flying a red flag. I studied it through the glasses,

fearing that it marked some hidden danger to navigation, some

recent wreck or some buoy or beacon that had been swept away.

Then the doctor came on board. After he had examined the state

of our health and been assured that we had no live rats hidden

away in the Snark, I asked him the meaning of the red flag.

"Oh, that is Darling," was the answer.

And then

Darling, Ernest Darling flying the red flag that is

indicative of the brotherhood of man, hailed us. "Hello,

Jack!" he called. "Hello, Charmian! He paddled swiftly

nearer, and I saw that he was the tawny prophet of the

Piedmont hills. He came over the side, a sun-god clad in a

scarlet loin-cloth, with presents of Arcady and greeting in

both his hands—a bottle of golden honey and a leaf-basket

filled WITH great golden mangoes, golden bananas specked

with freckles of deeper gold, golden pine-apples and golden

limes, and juicy oranges minted from the same precious ore

of sun and soil. And in this fashion under the southern sky,

I met once more Darling, the Nature Man.

...

CHAPTER XII—THE HIGH SEAT OF ABUNDANCE

...

The Snark was

lying at anchor at Raiatea, just off the village of Uturoa.

She had arrived the night before, after dark, and we were

preparing to pay our first visit ashore. Early in the morning

I had noticed a tiny outrigger canoe, with an impossible

spritsail, skimming the surface of the lagoon. The canoe

itself was coffin- shaped, a mere dugout, fourteen feet long,

a scant twelve inches wide, and maybe twenty-four inches deep.

It had no lines, except in so far that it was sharp at both

ends. Its sides were perpendicular. Shorn of the outrigger, it

would have capsized of itself inside a tenth of a second. It

was the outrigger that kept it right side up.

I have said

that the sail was impossible. It was. It was one of those

things, not that you have to see to believe, but that you

cannot believe after you have seen it. The hoist of it and

the length of its boom were sufficiently appalling; but, not

content with that, its artificer had given it a tremendous

head. So large was the head that no common sprit could carry

the strain of it in an ordinary breeze. So a spar had been

lashed to the canoe, projecting aft over the water. To this

had been made fast a sprit guy: thus, the foot of the sail

was held by the main-sheet, and the peak by the guy to the

sprit.

It was not

a mere boat, not a mere canoe, but a sailing machine. And

the man in it sailed it by his weight and his

nerve—principally by the latter. I watched the canoe beat up

from leeward and run in toward the village, its sole

occupant far out on the outrigger and luffing up and

spilling the wind in the puffs.

"Well, I

know one thing," I announced; "I don't leave Raiatea till I

have a ride in that canoe."

A few

minutes later Warren called down the companionway, "Here's

that canoe you were talking about."

Promptly I

dashed on deck and gave greeting to its owner, a tall,

slender Polynesian, ingenuous of face, and with clear,

sparkling, intelligent eyes. He was clad in a scarlet

loin-cloth and a straw hat. In his hands were presents—a

fish, a bunch of greens, and several enormous yams. All of

which acknowledged by smiles (which are coinage still in

isolated spots of Polynesia) and by frequent repetitions of

mauruuru (which is the Tahitian "thank you"), I proceeded to

make signs that I desired to go for a sail in his canoe.

His face

lighted with pleasure and he uttered the single word,

"Tahaa," turning at the same time and pointing to the lofty,

cloud- draped peaks of an island three miles away—the island

of Tahaa. It was fair wind over, but a head-beat back. Now I

did not want to go to Tahaa. I had letters to deliver in

Raiatea, and officials to see, and there was Charmian down

below getting ready to go ashore. By insistent signs I

indicated that I desired no more than a short sail on the

lagoon. Quick was the disappointment in his face, yet

smiling was the acquiescence.

"Come on

for a sail," I called below to Charmian. "But put on your

swimming suit. It's going to be wet."

It wasn't

real. It was a dream. That canoe slid over the water like a

streak of silver. I climbed out on the outrigger and

supplied the weight to hold her down, while Tehei

(pronounced Tayhayee) supplied the nerve. He, too, in the

puffs, climbed part way out on the outrigger, at the same

time steering with both hands on a large paddle and holding

the mainsheet with his foot.

"Ready

about!" he called.

I carefully

shifted my weight inboard in order to maintain the

equilibrium as the sail emptied.

"Hard

a-lee!" he called, shooting her into the wind.

I slid out

on the opposite side over the water on a spar lashed across

the canoe, and we were full and away on the other tack.

"All

right," said Tehei.

Those three

phrases, "Ready about," "Hard a-lee," and "All right,"

comprised Tehei's English vocabulary and led me to suspect

that at some time he had been one of a Kanaka crew under an

American captain. Between the puffs I made signs to him and

repeatedly and interrogatively uttered the word SAILOR. Then

I tried it in atrocious French. MARIN conveyed no meaning to

him; nor did MATELOT. Either my French was bad, or else he

was not up in it. I have since concluded that both

conjectures were correct. Finally, I began naming over the

adjacent islands. He nodded that he had been to them. By the

time my quest reached Tahiti, he caught my drift. His

thought-processes were almost visible, and it was a joy to

watch him think. He nodded his head vigorously. Yes, he had

been to Tahiti, and he added himself names of islands such

as Tikihau, Rangiroa, and Fakarava, thus proving that he had

sailed as far as the Paumotus—undoubtedly one of the crew of

a trading schooner.

CHAPTER XIV—THE AMATEUR NAVIGATOR

There are

captains and captains, and some mighty fine captains, I

know; but the run of the captains on the Snark has been

remarkably otherwise. My experience with them has been that

it is harder to take care of one captain on a small boat

than of two small babies. Of course, this is no more than is

to be expected. The good men have positions, and are not

likely to forsake their one-thousand-to-

fifteen-thousand-ton billets for the Snark with her ten tons

net. The Snark has had to cull her navigators from the

beach, and the navigator on the beach is usually a

congenital inefficient—the sort of man who beats about for a

fortnight trying vainly to find an ocean isle and who

returns with his schooner to report the island sunk with all

on board, the sort of man whose temper or thirst for strong

waters works him out of billets faster than he can work into

them.

The Snark

has had three captains, and by the grace of God she shall

have no more. The first captain was so senile as to be

unable to give a measurement for a boom-jaw to a carpenter.

So utterly agedly helpless was he, that he was unable to

order a sailor to throw a few buckets of salt water on the

Snark's deck. For twelve days, at anchor, under an overhead

tropic sun, the deck lay dry. It was a new deck. It cost me

one hundred and thirty-five dollars to recaulk it. The

second captain was angry. He was born angry. "Papa is always

angry," was the description given him by his half-breed son.

The third captain was so crooked that he couldn't hide

behind a corkscrew. The truth was not in him, common honesty

was not in him, and he was as far away from fair play and

square-dealing as he was from his proper course when he

nearly wrecked the Snark on the Ring- gold Isles.

...

The Snark

sailed from Fiji on Saturday, June 6, and the next day,

Sunday, on the wide ocean, out of sight of land, I proceeded

to endeavour to find out my position by a chronometer sight

for longitude and by a meridian observation for latitude.

...

Then, to the

south, Aneiteum rose out of the sea, to the north, Aniwa,

and, dead ahead, Tanna. There was no mistaking Tanna, for

the smoke of its volcano was towering high in the sky. It

was forty miles away, and by afternoon, as we drew close,

never ceasing to log our six knots, we saw that it was a

mountainous, hazy land, with no apparent openings in its

coast-line. I was looking for Port Resolution, though I was

quite prepared to find that as an anchorage, it had been

destroyed. Volcanic earthquakes had lifted its bottom during

the last forty years, so that where once the largest ships

rode at anchor there was now, by last reports, scarcely

space and depth sufficient for the Snark. And why should not

another convulsion, since the last report, have closed the

harbour completely?

I ran in

close to the unbroken coast, fringed with rocks awash upon

which the crashing trade-wind sea burst white and high. I

searched with my glasses for miles, but could see no

entrance. I took a compass bearing of Futuna, another of

Aniwa, and laid them off on the chart. Where the two

bearings crossed was bound to be the position of the Snark.

Then, with my parallel rulers, I laid down a course from the

Snark's position to Port Resolution. Having corrected this

course for variation and deviation, I went on deck, and lo,

the course directed me towards that unbroken coast-line of

bursting seas. To my Rapa islander's great concern, I held

on till the rocks awash were an eighth of a mile away.

...

I confess I

thought so, too; but I ran on abreast, watching to see if

the line of breakers from one side the entrance did not

overlap the line from the other side. Sure enough, it did. A

narrow place where the sea ran smooth appeared. Charmian put

down the wheel and steadied for the entrance. Martin threw

on the engine, while all hands and the cook sprang to take

in sail.

A trader's

house showed up in the bight of the bay. A geyser, on the

shore, a hundred yards away; spouted a column of steam. To

port, as we rounded a tiny point, the mission station

appeared.

"Three

fathoms," cried Wada at the lead-line. "Three fathoms," "two

fathoms," came in quick succession.

Charmian

put the wheel down, Martin stopped the engine, and the Snark

rounded to and the anchor rumbled down in three fathoms.

Before we could catch our breaths a swarm of black Tannese

was alongside and aboard—grinning, apelike creatures, with

kinky hair and troubled eyes, wearing safety-pins and

clay-pipes in their slitted ears: and as for the rest,

wearing nothing behind and less than that before. And I

don't mind telling that that night, when everybody was

asleep, I sneaked up on deck, looked out over the quiet

scene, and gloated—yes, gloated—over my navigation.

CHAPTER XV—CRUISING IN THE SOLOMONS

...

|

Nakuina, Emma

Metcalf:

Hawaii, Its People

and Their Legends.

Hawaiian

Promotion Committee, Honolulu, H.T., 1904.

|

Appendix

Johnson,

Martin: Through the South Seas with Jack London

T.W.

Laurie, London, 1913.

Internet

Archive

http://archive.org/details/throughsouthseas00johnrich

|

|

Page 90

I myself

spent a couple of days in Honolulu at this period, doing

some special camera work, and trying my luck at surf-board

riding.

This is said

to be one of the greatest sports in the world, but as it

takes several months, at the least, really to learn it, I

can hardly testify as to that.

But I do

know that I was nearly drowned, and managed to swallow a few

quarts of salt water before the fun wore off.

Jack stayed

at it for some time, and got so sunburned that he was

confined to his bed.

Let me say

here that it is my honest belief that only the native

Hawaiians ever

Page 91

really

learn the trick in all its intricacies, despite the fact

that, at several contests held, white men have come out

victorious.

surfresearch.com.au

Geoff Cater (2012-2017) :

Jack London : Cruise of the Snark, 1911.

http://www.surfresearch.com.au/1911_London_Royal_Sport.html

Johnson, Martin: Through the South Seas with

Jack London

T.W. Laurie, London, 1913.

Internet Archive

http://archive.org/details/throughsouthseas00johnrich

Page 90

I myself spent a couple of days in Honolulu at this period,

doing some special camera work, and trying my luck at surf-board

riding.

This is said to be one of the greatest sports in the world, but

as it takes several months, at the least, really to learn it, I

can hardly testify as to that.

But I do know that I was nearly drowned, and managed to swallow

a few quarts of salt water before the fun wore off.

Jack stayed at it for some time, and got so sunburned that he

was confined to his bed.

Let me say here that it is my honest belief that only the

native Hawaiians ever

Page 91

really learn the trick in all its intricacies, despite the

fact that, at several contests held, white men have come out

victorious.

Peeps At Many Lands: Australia

Frank Fox

Illustrator: Percy F. S. Spence (etc.)

Adam and Charles Black, London, 1911

Page 23

Few European or American children can enjoy such sea[23] beaches

as are scattered all over the Australian coast. They are beautiful

white or creamy stretches of firm sand, curving round bays,

sometimes just a mile in length, sometimes of huge extent, as the

Ninety Miles Beach in Victoria. The water on the Australian coast

is usually of a brilliant blue, and it breaks into white foam as

it rolls on to the shelving sand. Around Carram, Aspendale,

Mentone and Brighton, near Melbourne; at Narrabeen, Manly,

Cronulla, Coogee, near Sydney; and at a hundred other places on

the Australian coast, are beautiful beaches. You may see on

holidays hundreds of thousands of people—men, women, and

children—surf-bathing or paddling on the sands. It is quite safe

fun, too, if you take care not to go out too far and so get caught

in the undertow. Sharks are common on the Australian coast, but

they will not venture into the broken water of surf beaches. But

you must not bathe, except in enclosed baths in the harbours, or

you run a serious risk of providing a meal for a voracious shark.

Sharks are quite the most dangerous foes of man in Australia.

There have been some heroic incidents arising from attacks by

sharks on human beings. An instance: On a New South Wales beach

two brothers were bathing, and they had gone outside of the broken

surf water. One was attacked by a shark. The other went to his

rescue, and actually beat the great fish off, though he lost his

arm in doing so. As a rule, however, the shark kills with one

bite, attacking[24] the trunk of its victim, which it can sever in

two with one great snap of its jaws.

Children on the Australian coast are very fond of the water. They

learn to swim almost as soon as they can walk. Through exposure to

the sun whilst bathing their skin gets a coppery colour, and

except for their Anglo-Saxon eyes you would imagine many

Australian youngsters to be Arabs.

Facing Page 73

SURF-BATHING—SHOOTING THE BREAKERS

Project Gutenberg

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/25976/25976-h/25976-h.htm#beach