|

surfresearch.com.au

caton : hilo surf-riding, 1878 |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

Caton's dimensions

are within the range of most other early accounts and correspond with examples

held in contemporary collections.

See Alaia,

circa 1865.

Compare and contrast Thomas W. Knox : Surfing at Hilo, circa 1888.

Although earlier accounts (with judicious reading) imply that the riders slide diagonally across the wave face, this detailed account is notable for the empirical data (by noting the rider's motion relative to the compass points) that dramatically illustrates that the rider is transversing the wave face.

DelaVega

(ed.

2004) notes on page 14 ...

Tom Blake

and Ben Finney referred to Caton's account to show that ancient surfers

sIide waves like we do, "they slid the wave for the same reason we do today;

that is, to get away from the breaking or foaming crest of the wave."

Hawaiian

Surfriders, p. 42. Finney

and Houston (1999)

page ?

Finney

and Houston (1999) note seven ancient surf breaks at Hilo,

Hawai'i.

Page 28.

This transcription

is collated from quotations and discussion in Tom Blake's Hawaiian

Surfriders, pages 41 to 43, and is undoubtedly, incomplete.

The difficulties

in the transcription are most noticeable at the end of the account where

I have attempted to limit the influence of Blake's 20th century perspective.

The wind was

light, but immense seas were rolling in through the broad opening into

the bay in front of which was our place of observation.

On our left

was an area covered with large volcanic rocks, extending for almost half

a mile into the bay.

Near the shore

the tops of many of these appeared above the water when it was still, the

depth of which gradually increased sea-ward.

As the big

seas chased each other in from the open ocean the west end first reached

this rocky bed, and the instant the bottom of the wave met this obstruction,

its rotary motion was checked, and immediately the comb on the top was

formed so that the foamy crest seemed to run along the top of the wave

from west to east, as successive portions of it reached the rocky bottom.

By this, also,

the easterly portion of the wave was also retarded in its progress towards

the shore, while to the west it dashed forward in its unchecked career.

The effect

of this was to bend the wave into a crescent form.

Page 243

On our left,

over the rocky bed, perhaps half a dozen of these huge crested waves would

be chasing each other, the most advanced being the least perfect in form,

till finally they became quite broken down and dissolved into a great field

of white foam, in the midst of which the vast volcanic boulders showed

themselves.

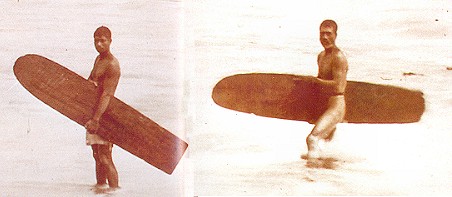

Three bathers

appeared, stripped to their breech-cloths, each with his bathing-board,

which was about three quarters of an inch thick, seven feet long, coffin-shaped,

rounded at the ends, and chamfered at the edges; it was about fifteen inches

wide at the widest near the forward end, and eleven inches wide at the

back end.

When I examined

them carefully after the sport was over, I observed that one of these boards

was considerably warped, but its owner said that did not injure it for

use.

The bathers

started out, their boards under their arms, in this seething sea of foam,

wading among the rocks where only an expert, familiar with the ground,

could avoid being dashed to death in a moment, -sometimes wading, sometimes

swimming, and sometimes stopping on high rocks to steady themselves and

take advantage of the situation, till they reached the regular wave formations,

though these were still badly broken up, when they struck out on their

boards, diving under the waves as they met, making their way rapidly outward

and towards the east end of the breakers.

Here they

remained floating on their boards till an unusually large and regular wave

approached and commenced breaking, its great foaming crest arching over

apparently several feet, the milky foam falling upon the front declivity

of the wave several feet above its base.

This was the

condition desired by the surf-bather.

One instantly

dashed in, in the front of and at the lowest declivity of the advancing

wave, and with a few strokes of hands and feet established his position;

then, without further effort shot along the base of the wave to the eastward

with incredible velocity.

Naturally

he came towards the shore with the body of the wave as it advanced, but

his course was along ...

Page

244

... the foot

of the wave and parallel with it, so that we only saw that he was running

past with the speed of a swift-winged bird.

He kept up

with the progress of the breaking crest which moved from west to east,

as successive

portions of

the rest of the wave took the ground, as I have described.

So soon as

the bather had secured his position he gave a spring and stood upon his

knees upon the board, and just as he was passing us, when about four hundred

feet from the little penisular point where we stood, he gave another

spring and stood on his feet, now folding his arms upon his brest, and

now swinging them about in wild ecstasy in his exhilarating flight.

break

But all this

must be enjoyed rapidly, for scarcely a minute elapsed from the time he

started till he was far away to the right, where he abandoned the exhausted

wave, and with a few vigorous strokes propelled himself into shallow water

and waded ashore with his board under his arm; he came up to us as

calm, at least, as those who had witnessed his wonderful feat.

I have followed

the first who started, without noticing the others, for only thus could

I give a clear idea of the exhibition.

But the others

were not idle in the mean time; the last of the three had taken his wave

before the first had concluded his course, but the progress was so rapid

and the time so short that I glanced at the others and confined my study

to the first.

But these feats

were several times repeated by all the bathers, and thus I was enabled

to make the study much more complete than possible by observing a single

exhibition.

Not every

attempt to take the wave was a success.

Several times

the bathers seemed to be drawn up the front acclivity of the wave till

brought within the reach of the comb, when the attempt was instantly abandoned;

they dove under the wave and soon came up quite beyond it, and waited for

another on which to make the passage.

The bathers themselves were unable to explain what it was that propelled them with such astonishing velocity ...

Page 245

... along

the foot of the wave, and I have conversed with a lawyer of distinction

now practicing in this country, who was born and brought up at Hilo, and

was himself a successful surf bather.

He could only

say that the propulsion was by the action of the water, which, indeed,

was very manifest, but 'how' he would not venture an opinion.

The inclination

of the board to climb up the acclivity - if, indeed, such is the case -

when the wave is rolling towards the bather, and so producing a current

downward, seems contrary to what we should expect.

This propulsion

parallel with the wave, I think, only occurs when a comb is breaking on

the top of the wave, and then it is that the foot of the wave in front

is most distinctly defined, while the unbroken swell is very irregular

and much deformed.

That there

is a rapid current rushing along at the foot of the wave at right angles

to its general course I cannot believe.

A block of

wood thrown in where the bather started would no doubt simply rise up over

it and be left behind to again surmount the succeeding wave, much less

would it dart off almost like a flash and maintain its position in front

of the wave.

The only solution

to the problem which I will venture to suggest is, that by placing the

bathing-board at a certain angle to the direction of the moving water in

the wave an impetus is given to it in a direction not in accord with the

impelling force, as by trimming the sails of a ship, so that the wind will

strike them obliquely the vessel is propelled in a direction different

from the course of the wind.

If the results

were more marked than we should expect from the cause suggested, I may

say that we are not sure that we are acquainted with the force and direction

of all the currents which accompany a wave of the sea.

At all events,

I hope that what I have said will induce others more competent to study

the subject, and give a more satisfactory explanation of the striking facts

which I have detailed.

I do not think

it will prove more difficult of explanation than is the action of the boomerang

from the hands of the Australian native.

|

Caton, John Dean (1812-1895) : Miscellanies Houghton, Osgood & Co. Boston. The Riverside Press, Cambridge. 1880 Chapter XV Surfbathing at Hilo, on the Island of Hawaii. Notes of Travel, 1878. Pages 242 to 245. |

|

|

2. "the breaking

crest, which moved from west to east"

This is the critical

empirical data (by noting the rider's motion relative to the compass points)

that dramatically illustrates that the rider is transversing the wave face.

3. "he

gave a spring, and stood upon his knees upon the board, ... he gave another

spring and stood upon his feet"

Indicates that the

rider stood after first taking a kneeling position.

4. "one and

one-half inches thick, seven feet long, coffin shaped, rounded at the ends,

chamfered (beveled -

Blake) at the edges; about fifteen inches wide at the widest point

near the forward end, and eleven inches wide at the back end."

Caton's dimensions

are within the range of most other early accounts and correspond with examples

held in contemporary collections.

See Alaia,

circa 1865.

This report

also specifically notes the charateristcs of the template - 15'' at the

wide-point and a 11'' pod.

This favorably compares

with 'Resolution'

midshipman, George Gilbert's report circa 1778

...

"16

inches in breadth at one end and about nine at the other; and is four or

five inches thick, in the middle tapering down. " Dela

Vega (ed, 2004) Page15.

5. "stripped

to their breach cloths or malos"

This is consistant

with most contemporary 19th century illustrations.

6. "natives

could not explain why ..."

This indicates the

complexity of breaking wave mechanics and the dynamics of succesful

surf-riding.

Cleary, a failure

to theoretically understand the processes was not a deterent to practical

success.

The theoretical

difficulties are further evidenced by some of Blake's comments.

7. "the

friction of the slippery board against the water is very small"

My physics is a

bit rusty, but I think that the friction on the board is significant -

overwise the board would sink.

More work/thought

required.

8. "to

catch up with the incoming swell ... by paddling the board with the hands

and arms."

One of the most

common misunderstandings by surfriders - technically the wave "catches"

the rider.

Pedant's Corner

: A Technical Anaylsis of the Take-Off

Propulsion is

necessary to achieve the ‘take-off’.

The rider ‘takes

off’ by positioning the board where the angle of the wave face is steep

enough for the board to

achieve minimum

planning velocity.

Since personal surf-craft

cannot normally paddle faster than wave speed, this is a critical calculation.

In this case, the

rider does not ‘catch’ the wave – rather the wave ‘catches’ the rider.

If there is a sense

in which the rider 'catches' the wave, then it is not as in 'catching a

ball' and more like

'catching a (moving)

train'.

As well as paddling

into position, by the rider maximising their paddling velocity, the radical

acceleration to

take-off velocity

is reduced.

For stand-up surf-riders,

the take-off is further complicated by the radical change in position from

prone to

standing.

|

(Bishop Museum) |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

As the big seas chased each other in from the open ocean, the west end first reached the rocky bed, and the instant the bottom of the wave met this obstruction, its rotary motion was checked, and immediately, the comb on the top was formed, so that, the foamy crest seemed to run along the top of the wave from west to east, as successive portions of it reached the rock bottom.

As soon as the bather had secured his position, he gave a spring, and stood upon his knees upon the board, and just as he was passing us, when about four hundred feet from the little peninsula point where we stood, he gave another spring and stood upon his feet (3), now folding his arms upon his breast, and now swinging them about in wild ecstasy, in his exhilarating flight.

Here Blake paraphrases Caton, rather than quote him directly, and I have adjusted the text to highlight what I think is Caton's input ...

... these boards as being about one and one-half inches thick, seven feet long, coffin shaped, rounded at the ends, chamfered (beveled - Blake) at the edges; about fifteen inches wide at the widest point near the forward end, and eleven inches wide at the back end. (4)

... boards of the aliea, or thin design, were usually made of koa or wood of the breadfruit tree.

The surf bathers ... stripped to their breach cloths or malos, before going in the water. (5)

... the natives

could not explain why they were propelled shoreward with such astonishing

speed, nor could I (Mr. Caton) explain it myself (himself),

nor could my (his) friends.

He hoped that

someday, someone would study the question and find an answer to it. (6)

To continue the narrative,

Blake goes on to suggest a, not altogether satisfactory, solution ...

The answer

is relatively simple. Gravity does the trick.

The front

slope of the wave on which one slides presents a down-hill path, while

the friction of the slippery board against the water is very small. (7)

It's the same

as skiing on a snow-covered hill, and there is no doubt as to what makes

one slide down a hill on skis.

However, in

skiing, one can start down hill from a stationary position, while in surfriding

some momentum must first be attained , to catch up with the incoming swell.

2. "the breaking

crest, which moved from west to east"

This is the critical

empirical data (by noting the rider's motion relative to the compass points)

that dramatically illustrates that the rider is transversing the wave face.

3. "he

gave a spring, and stood upon his knees upon the board, ... he gave another

spring and stood upon his feet"

Indicates that the

rider stood after first taking a kneeling position.

4. "one and

one-half inches thick, seven feet long, coffin shaped, rounded at the ends,

chamfered (beveled -

Blake) at the edges; about fifteen inches wide at the widest point

near the forward end, and eleven inches wide at the back end."

Caton's dimensions

are within the range of most other early accounts and correspond with examples

held in contemporary collections.

See Alaia,

circa 1865.

This report

also specifically notes the charateristcs of the template - 15'' at the

wide-point and a 11'' pod.

This favorably compares

with 'Resolution'

midshipman, George Gilbert's report circa 1778

...

"16

inches in breadth at one end and about nine at the other; and is four or

five inches thick, in the middle tapering down. " Dela

Vega (ed, 2004) Page15.

5. "stripped

to their breach cloths or malos"

This is consistant

with most contemporary 19th century illustrations.

6. "natives

could not explain why ..."

This indicates the

complexity of breaking wave mechanics and the dynamics of succesful

surf-riding.

Cleary, a failure

to theoretically understand the processes was not a deterent to practical

success.

The theoretical

difficulties are further evidenced by some of Blake's comments.

7. "the

friction of the slippery board against the water is very small"

My physics is a

bit rusty, but I think that the friction on the board is significant -

overwise the board would sink.

More work/thought

required.

8. "to

catch up with the incoming swell ... by paddling the board with the hands

and arms."

One of the most

common misunderstandings by surfriders - technically the wave "catches"

the rider.

Pedant's Corner

: A Technical Anaylsis of the Take-Off

Propulsion is

necessary to achieve the ‘take-off’.

The rider ‘takes

off’ by positioning the board where the angle of the wave face is steep

enough for the board to

achieve minimum

planning velocity.

Since personal surf-craft

cannot normally paddle faster than wave speed, this is a critical calculation.

In this case, the

rider does not ‘catch’ the wave – rather the wave ‘catches’ the rider.

If there is a sense

in which the rider 'catches' the wave, then it is not as in 'catching a

ball' and more like

'catching a (moving)

train'.

As well as paddling

into position, by the rider maximising their paddling velocity, the radical

acceleration to

take-off velocity

is reduced.

For stand-up surf-riders,

the take-off is further complicated by the radical change in position from

prone to

standing.