surfresearch.com.au

the catalogue #600

whaleboats

the catalogue #600

whaleboats

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

surfresearch.com.au

the catalogue #600 whaleboats |

|

| 1945 RAN

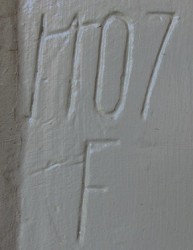

Montagu Whaler #872 and #1107 F 27 ft

|

#600

|

|

Length :

|

27 |

ft |

0

|

inches | L2: | |

|

Width :

|

75

|

inches |

Wide Point :

|

0

|

inches | |

|

Bow :

|

|

inches |

Stern:

|

|

inches | |

|

Draught :

|

17

|

inches |

Transom :

|

0

|

inches | |

|

Nose Lift :

|

inches |

Tail Lift :

|

inches | |||

|

Displacementt :

|

27 | cwt |

Volume :

|

litres | ||

| Weight : | kilos |

| Emblem

of HMAS Queenborough on the bow. 4.5 inch diameter HMAS Queenborough was one of eight Q Class destroyers built for the Royal Navy, commissioned on 30 November 1942. She was transferred on loan from the Royal Navy to the Royal Australian Navy and commissioned as HMAS Queenborough at Sydney on 20 October 1945. On 10 July 1963, she was paid off to the control of the General Manager, Williamstown Dockyard but recommissioned on 28 July 1966, for service as a training ship, before finally decommissioned on 7 April 1972. http://www.navy.gov.au/hmas-queenborough |

|

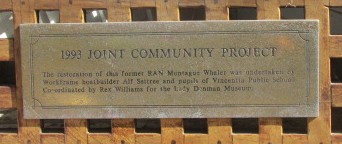

| SIGNAGE Boat 1993 Joint Community Project

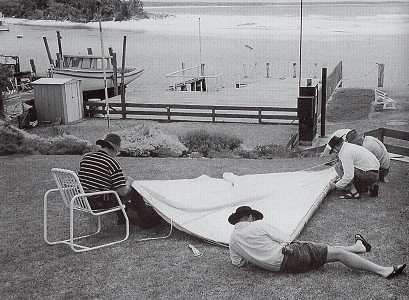

This restoration of this former Montague Whaler was undertaken by Workframe boat builder Alf Settree and pupils of Vincentia Public School Co-ordinated by Rex Williams for the Lady Denman Museum. External

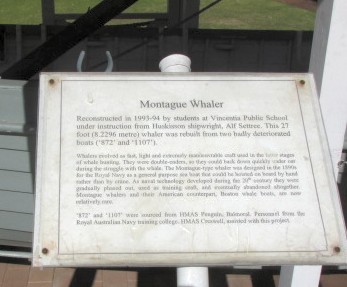

Montague WhalerReconstructed in1993-94 by students at Vincentia Public School under instruction from Huskisson shipwright, Alf Settree. This 27 foot (8.2299 metres) whaler was rebuilt from two badly deteriorated boats ('872' and '1107'). Whalers evolved as fast, light and extremely manoeuvrable craft used in the latter stages of whale hunting. They were double-enders, so they could back down quickly under oar during the struggle with the whale. The Montague-type whaler was designed in the 1890s for the Royal Navy as a general purpose sea boat that could be hoisted on board by hand rather than by crane. As naval technology developed during the 20th century they were gradually phased out, used as training craft, and eventually abandoned altogether. Montague whalers and their American counterpart, Boston whale boats, are now relatively rare. '872' and '1107' were sourced from HMAS Penguin, Balmoral. Personnel from the Royal Australian Navy framing college, HMAS Creswell, assisted with this project.  |

|

|

|

Centreboard

lever

1107 F

|

|

| The Montagu

Whaler was 27ft LOA (Length Over All), although there was a shorter 24ft

version, 6ft 3ins in the beam and with a

draught of 1ft 5ins with the centre-board plate up. It was double ended and constructed in various timbers, depending on the location of manufacture. Some reported timbers include wych or sand elm in England, or mahogany at Malta, elm or mahogany on oak, Mahogany planking on Canadian elm ribs, and in the Far East the boats were built in exclusively of teak. . |

Whaleboat under sail, HMS

Suffork, c1930.

|

| Australia's most significant whaleboat, commanded

by naval surgeon

and explorer George

Bass, entered

Jervis Bay on December 18, 1797. This boat, unlike its predecessors, Tom Thumb and Tom Thumb (II), was not named, but was one of the first vessels built in the colony from local cedar and banksia. Bass wrote that Hunter had only had one boat available and that was the whaleboat ... for coastal exploration it was ideal so long as we did not venture too far from shore. It is variously known as the whaleboat, the Governor's whaleboat, or Bass's whaleboat. Bass arrived in Port Jackson aboard HMS Reliance, under the command of Henry Waterhouse, in September 1795, along with John Hunter, the new governor, midshipman Matthew Flinders, and Bass's assistant, William Martin. Hunter was returning to Australia, having served under Arthur Phillip in the First Fleet, where he was instrumental in the exploration of the colony, culminating in a Chart of the coasts and harbours of Botany-Bay, Port-Jackson and Broken-Bay, as survey'd by Capt.n John Hunter of H.M.S. Sirius. For Bennelong, also aboard the Reliance, his return to his native land was a difficult home-coming. Bennelong and another local Aboriginal, Yemmerrawanne, had sailed to England with Phillip on the Atlantic in 1792, the year after she was the first vessel to shelter in Jervis Bay on her voyage to Port Jackson |

Bass Postage

Stamp

Australia Post, 1966. |

The entrance to Lake Illawarra is dominated by Windang Island, in the local Thurwal language Gang-man-gang, the wreck of a large canoe that had brought the human creatures to this land who became the native animals. They had stolen the canoe from the human creature that was the whale. He had swum desperately after the fugitives but with the destruction of his canoe, the whale now cruised the coastline, blowing water through the gash in his head inflicted in his earlier battle with the starfish. Right: Windang Island and Lake Illawarra Entrance, 2015. 96.5wavefm http://www.wavefm.com.au/ |

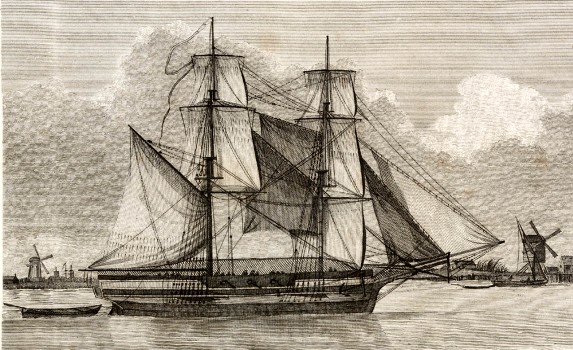

| The Lady Nelson's boat was instrumental in

the exploration of Jervis Bay by Lt. James Grant in March

1801. After waiting outside the heads overnight, Grant sent the first mate in the ship's boat to find a suitable anchorage on the morning of the 11th. On the boat's return, with one of the local Aboriginals, by half-past ten she anchored in four fathoms water, fine sandy bottom. The boats were thereafter extensively employed over the next three days before the Lady Nelson departed early on the 13th March. Pleadon (1990) reports that the Lady Nelson got under way having been towed out of the bay by the ship's boat. |

James Grant: Lady Nelson and ship's boat, Thames, 1799.

|

|

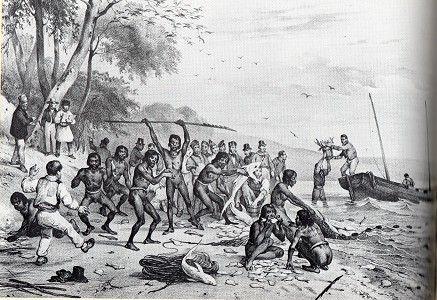

Louis Auguste de

Sainson:

Sharing the catch, Jervis Bay, 1826. Dumont D'Urville: Two Voyages to the South Seas Volume 1: Astrolabe 1826-1829 Translated by Helen Rosenman Melbourne University Press, 1987, facing page 91. At the National Gallery of Australia |

Right: Whaleboat

Elizabeth

under sail off Sam Remo, 1998.

|

|

| History: Whales, Men and Boats | Whaleboat : References, Appendix, Notes |

| Jervis Bay Whaleboat Crew : Project 2015-2019 | JBWC : Information for Members |

Sculpture dedicated to Alf Settree,

1914-1998.

Jervis Bay Maritime Museum, Huskisson. Sculptor: Denis Davis OAM |

|

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |