|

surfresearch.com.au

ancient hawaiian surfboards: 1940 |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

Tom

Blake (1902-1982?)

probably compiled some of his academic research for the book

at the Bishop

Museum, Honolulu following his restoring the museum's two

large olo boards,

circa 1925. (5)

His historical

account

of the constuction and use of ancient Hawaiian surfboards

identifies and

extensively quotes from several of the sources discussed

above.

Despite access

to

the exensive resources of the Bishop, some of the earliest

material, for

example the accounts by Cook's crew (see part 2), probably was

not available.

Unlike

previous commentators

(6),

Tom Blake's analysis was assisted by an wealth of practical

surfriding

experience (7), evident in Blake building and riding a

reproduction

of an ancient design. (8)

An adult

'convert'

to surfriding (9), Blake enthusiastically promoted the

activity

in the press (10), print (11) and importantly,

water photography.

(12)

His enthusiasm

was

further fuelled, but not dominated by, a commericial interest

apart from

the financial benefits of of publication (13),

principally the sale

of his surfboard designs.14

In some

repects,

this enthusiasm may have led Blake to over-state or embellish

his work.

Surfriding was

a

royal ancient Hawaiian sport, however it was not the

only one (15)

and

it was not the exclusive preserve of the nobility as in some

european contexts.

(16)

Tom Blake

attended

High School but did not attend colledge to complete his

education.(17)

It is likely

that

Blake had copies or access to a significant number of

surfriding articles

published in Hawaiian newspapers, several of which he wrote

himself. (18)

These may

contain

some of the original sources later included in The

Hawaiian Surfboard,

along with selections from Blake's articles. (19)

It is also

possible

that Bishop Museum staff were able to direct Blake in locating

suitable

sources.

In his account

of

restoring Paki's boards, Tom Blake writes of consultations

with "Mr.

Bryan, curator of the museum' (20)

While Tom Blake

did not read Hawaiian, no doubt some Bishop Museum staff were

available

to translate any early documents written in the native

language, post 1800.

(21)

Blake

initially approached

the National Geographic Magazine in 1930 with a

x,000 word

article and a selection of surfriding photographs.

While the

editor

was interested in the images, the article was rejected and a

2,000 word

alternative requested. (22)

In 1930 Tom

Blake

published the first of two magazine articles (23),

probably culled

from his original draft intended for the National

Geographic.

(24)

Both the

articles

would later be incorporated into The Hawaiian Surfboard.

(25)

Apparently the

second

article forwarded to the National Geographic was

not acceptable

either, although a selection of the photographs, with Blake's

explanatory

captions, was eventually printed in May 1935. (26)

The editor was

able

to link Blake's photographs with another article on American

aviatrix

Emelia Earhart's stop-over in Hawaii on her attempt at

crossing the

Pacific.

The surfriding

images

included one with Earhart riding in a canoe.(27)

While some of

the

published images dated back to before 1930, this was certainly

a comtemporary

photograph.

6.2

The

first chapter is a compliation and analysis of ancient

Hawaiian legends

with a surfriding theme, although there are numerous

digressions on associated

topics.

If this style

was

carried over from the article prepared for the National

Geographic,

it might be one of the reasons for that document's rejection.

On page 18,

Blake

identifies two ancient surfboard designs by quoting Fornander

(5.9).

(22)

Blake notes

that

the two designs, apart from the variation in structural

features, are intended

for different surfriding conditions.

"This passage (Fornander) shows the different boards best suited to different kinds of waves." (23)

He developes this basic report into detailed descriptions, apparently collated from various sources.

"The

alaia

as the thin board was called, ranged from a few feet, a

child's size, to

about twelve feet long for adults.

The

larger

one being about one and one half inches thick through the

center, levelling

off on both top and bottom to about one-quarter inch at

the edges.

<...>

The

comparatively

small size of the alaia board made it easy to handle in

such waves.

It was

made

of the hardwood of the koa and breadfruit tree.

The Olo, indicating the longer boards, was of wili wili wood, a porus light wood like balsa, in fact, wili wili is Hawaiian balsa, just as koa is Hawaiian mahogany, of which there are sixty-seven different kinds in the world." (24)

Blake's

rigorous

distinction between the timbers suitable for each design may

be contradicted

by Ellis' (3.5) report of 1825:

"a board

...generally

five or six feet long ... usually made of the wood of the

erythrina (willi

willi)" (25)

He argues strongly, for boards of considerable length, that structual limitations of willi willi timber were a major factor in adopting the thick design.

"An alaia designed board of wili wilIi would not be strong enough, therefore, the Olo type was about six inches thick maximum, down the center of the board, and made of convex top and bottom so the edges beveled off to about one-half inch all around." (26)

The two olo examples held by the Bishop museum are examined and Blake appears to concede that as they are made of koa, there is apparently confict with the analysis above.

"The

Hawaiian

chief, Pakai, was a famous surf rider around the 1830

period.

His two

great

surfboards are now in the Bishop Museum.

Although

these

two boards are of Olo design, long and thick, and of heavy

koa wood, I

feel that koa was second choice for the making of this

long board.

Wili

wilIi

being generally used.' (21)

Olo boards

were made

of willi willi, unless they were made of something else. (22)

To confuse the

issue

further, Blake subsequently claims exclusive royal use for the

willi willi

olo board.

I also believe that while the wili wili board of Olo design was reserved for the use of the chiefs, the koa board of Olo design was not restricted to the alii (chiefs), but was for general use because of the scarcity of wili wili wood and plentiful occurrence of koa." (23)

The koa wood olo boards require Blake to substantially modify Thrum*'s emphatic1896 report (see 5.2)

"It is well known that the olo was only for the use of the chiefs" (24)

A detailed discussion of the olo board's riding charareterics are discussed later in Blake's book (and in this paper).

"How the Olo long board was especially adaptable to the swells or unbreaking wave, will be clearly brought out in a later discussion on modern surfing." (25)

In contrast to Blake's somewhat unsatisfying account of the olo board, the reported response from Duke Kahanamoku is probably closer to the mark.

"Duke

Kahanamoku's

answer to the reason for the old wili wilIi boards being

reserved for the

chiefs is that it was a very scarce and valuable wood.

Therefore,

the

chiefs had wili wili boards for the same reason that a man

has a Rolls-Royce

automobile today, that he is wealthy and can afford it." (26)

6.3

On

page 30 Blake investigates the religious ceremonies

associated with

surfboard construction, first outlined by Thrum* in 1896.

Note that it

has

been previously argued that Thrum's* account bears significant

similarities

to accounts of ceremonial rites identified with ancient

Hawaiian canoe

building, see 5.2.

His inital

assumption

is probably correct, to a degree:

"The routine of surfboard making was similar, no doubt, if the board belonged to a chief, to that of canoe building." (27)

At best, these

rites

would only apply to a small percentage of all boards ever

constructed.

Futhermore, to

assume

an equality of status between the surfboard and the canoe in

ancient Hawaiian

culture is questionable.

Despite the

ancient

Hawaiian's committment to surfriding documented in their

legends, certainly

the canoe held the premier position in this maritime culture.

Blake selectively quotes David Malo to illustrate the canoe building process.

"Malo

says:

' The building of a canoe was an affair of religion.

They took

with them to the mountains as offerings, a pig, coconuts,

kuma (red fish),

and awa.

Having

come

to the tree they sacrificed these things to the gods with

incantations

and prayers and there they slept.

The

kahuna

alone planned out and made the measurements for the inner

parts of the

canoe.

The

inside

was finished off by means of the adze (made of lava or

other stones).

The

ceremony

of lolo?, was consecrating the canoe, in which the diety

was again approached

in prayer.

This was

done

often after the canoe had returned from an excursion at

sea.' " (35)

As noted in

3.5,

given the status of Malo's account as from one who grew up

under the tradional

culture and its early composition, it is important what he did

not say

about surfboards.

In an extensive

list of 30 items ranked in importance, tilted The

Valuables and Possessions

of the Ancient

Times

(Chapter

22, Pages 76 to 81), he does not specifically include

surfboards.

Canoes are

rated

very highly (points 7 and 8), immediately following items of

royal or religious

significance,

Malo provides a

six page account of the construction process and the

accompanying religious

ceremonies, from which Blake selectively quotes.

6.4 Blake returns to ancient board design on page 30, with a quotation credited "Kealakakua Bay ... of 1783 vintage, by Ellis, Captain Cook's historian." (37) and he concludes :

"The

boards

used by these natives were undoubtedly of the aleia or

thin type.

The Olo,

or

long thick board, would not be practical on so short a

surf, and rocky

a shore.

The long

surf

and unbroken swells are better suited to the Olo board." (38)

Blake might

also

have noted that the report is from a southern coast in the lee

of the prevailing

swells.

For a detailed

discussion

of the location of Cook's reports, see 2.8.

A further

quotation

by "Archibald Campbell, in his work, Voyage Around the

World,

1806-1812" (39) follows without discussion

or analysis,

see 3.1.

Another

quotation,

credited as by "Ellis, in a work of 1823 ", is an

edited version

of the Rev. William Ellis' account

of surf-riding

at Waimanu, published 1831. (40)

See 3.5

Note that the

quotation

does not include Ellis' report, noted above 6.2, that appears

to conflict

with his analysis.

"a board ...generally five or six feet long ... usually made of the wood of the erythrina (willi willi)" (41)

It is

possible, but

unlikely, that the full text was not available to him.

Blake directs

his

comments to Ellis' account of juvenile surfriders and the

drying, oiling

and storage of the board:

"I can

say

that many children, boys of about eight years old, can

ride the waves on

a surfboard.

True,

they

stay near shore, but master the same technique as their

older brothers.

The great

regard of the ancient Hawaiian for his surfboard,

displayed by his care

in drying and oiling it and even wrapping it in 'tapa and

hanging it in

his house, gives some idea of the value and high place the

surfboard had

in his life." (42)

6.5

Next, Blake quotes the full entry by Malo on surfboards (43)

and

emphasises his historical significance.

" the

work

of Malo, the Hawaiian historian, with translations by

Emerson.

Malo was

born

in 1793, was known to be writing in 1832, and died in

1853.

An

honest,

conscientious writer, he devotes but a short chapter to

surf riding as

practiced by the old Hawaiians.

However,

his

work is invaluable in building the chain of surfboard

customs." (44)

Blake notes Emerson's objection to the extreme length of "four fathoms or even longer" suggested by Malo, and suggests a plausible interpretation.

"Emerson found him over

estimating

distances or sizes on two occasions.

I believe Malo meant yards when

he used fathoms.

How many of you know how long a

fathom is? Six feet." (45)

Emerson's notes do refer to this one

case

of over-estimating, Blake must have identified another instance

somewhere

in the book.

Blake's suggestion appears

reasonable,

the adjusted lengths attributed to Malo would then cover a range

of 3 feet

to longer than 12 feet, however full agreement probably requires

further

evidence.

Blake's analysis of design features

of

the olo board, previously established by reference to Fornander

circa 1910

(5.9 ), is now 'confirmed' by Malo circa 1839 and once again the

status

of Paki's boards is apparently side-lined.

"Malo's statement that a

'narrower

board was made from the wili wili,' bears out my theory that

the Olo, or

long type board, was not usually made of the hardwoods from

koa and breadfruit

trees, but of the soft, light wood of the wilIi wili tree.

Those koa boards of chief

Paki's

in the the Bishop Museum, are really a bit too heavy,

although handling

well in the water, and riding the big swells in a good

manner.

I choose, for the big waves, a

hollow

board weighted with lead to make it steady. I find seventy

pounds a good

weight for a hollow board for big surf." (46)

6.6

The notes confirm Blake's extensive experiments with these

designs, apparently

building and riding a reproduction model in the process of

developing his

hollow designs. (47)

A detailed account of the restoration

of Paki's boards follow, an unprecedented and unique opportunity

for Blake's

research. (48)

It is reproduced here in full:

"I

recently

had the privilege, and hard work, of restoring Paki's

museum boards to

their original condition.

For

twenty

years or more they had been hanging or tied with wire

against the stone

wall on the outside of the museum, covered with some old

reddish paint

and rather neglected.

My

inquiries

into the art of surfriding disclosed to me the the true

value of these

two old koa boards. They are the only two ancient

surfboards of authentic

Olo design known to be in existence today.

I made an

appeal to Mr. Bryan, curator of the museum, to restore the

boards to their

former unpainted finish and begged a more worthy location

for their display

in the museum.

Permission

was

refused by the directors on the grounds that I might

injure the evident

antiquity of Paki's boards.

After two

years, I made a second appeal, and was granted permission

to restore them

and given promise of a more suitable location inside the

building to keep

them.

In the

restoration

of Paki's old boards, I discovered that they are

undoubtedly much older

than anyone suspected.

In fact,

they

were probably already antiques when Paki acquired them.

I shall

give

my reasons for this inference.

Underneath

the

old red paint was several coats of blue paint. and

underneath, that

were hard layers of a sand colored paint, and underneath

that in many spots

was marine deck seam compound filling in worm eaten parts

of the board.

On the

largest

board, the tail, in part, was rebuilt of California

redwood to give the

board its original shape.

Paki,

according

to Stokes, was born on Molokai in 1808, and lived until

1855.

It was

probably

around 1830 when Paki was man enough to handle these big

boards.

The old

whaling

ships were sometimes seen in Honolulu harbor then and the

several kinds

of paint beneath the old red surface, also the ship's deck

seam compound

and redwood tail patch were available even before 1830.

Therefore,

I

assume that Paki dug up these two fine old discarded

worm-eaten boards,

had the redwood patch put on one, the deck caulking

compound and paint

on both, and painted them, so he could use them himself.

In their

restored

condition, the worn holes and patches show clearly under

the varnish finish.

Two fine

examples

of a now extinct design are these two old board on which

Chief Paki once

rode the Kalahuewehe surf at Waikiki.

It is

said

that Paki would not go surfriding unless it was too stormy

for anyone else

to go out.

His

reputation

of going out only in big surf is the natural thing when a

man gets beyond

his youth. Today, it takes big waves to get the old timers

out on their

boards." (49)

Blake's

estimated

history of Paki's boards indicates their construction

possibly pre-dates

Cook's visits in 1778 and 1779.

Elements of

Blake's

reconstructed board history appear to parallel in detail and

date a first

person report by Chester Lyman from Waikiki in 1846. (50)

See 4.2

Blake

undoubtedly

did not identify this account, it is inconceivable he would

not have used

it if available.

Specifically,

Lyman

notes:

"The

young

chiefs are all provided with surfboards, which are kept in

the house above

mentioned.

They are

from

12 to 20 feet long, 1ft wide, & in the middle 5 or 6

inches thick,

thinning towards the

sides

&

ends so as to form an edge.

Some of

these

have been handed down in the royal family for years, as

this is the royal

bathing place." (51)

Lyman

describes the

thick olo board (although the narrow width is unusual), makes

the earliest

assocciation between this design and Hawaiian royalty and

identifies Waikiki

as a royal surfing location.

Unfortunately,

he

does not identify the timber used to build these boards or

their relative

weight.

Blake's

assumption

"that Paki dug up these two fine old discarded worm-eaten

boards"

appears a weaker, if more dramatic, option to Lyman's reported

"handed

down in the royal family for years".

Lyman

continues:

"None of these belonging to Kamehameha 1st are now left, but one used by Kaahumanu & others belonging to other distinguished Chiefs & premiers are daily used" (52)

Malcom Gault

Williams

notes Kaahumanu (1768-1832) was the favorite wife of the noted

surfrider

Kamehameha the Great (1753?-1819) and served as regent from

1824 to1832

(53)

Lyman's claim

that

one of the boards was "used by Kaahumanu"

would possibly

date the board's construction around 1800-1810, likely her

mature surfriding

years, but it may be older.

He also notes:

"according to ... I'i, they liked to surf Kooka, a break located at Pua'a, in north Kona"(54)

I am unable to identify the specific island or the location in Finney and Houston (1996). (55)

6.7 Blake extensively quotes, and occassionally paraphrases, John Caton's report from Hilo in 1880 (see 4.9) between pages 41 and 42 to forceably argue that ancient Hawaiians:

"slide

the

wave to get away from the break"

and

"stood

upon

the surfboard in olden times just as we do today" (56)

Although some

earlier

accounts, with judicious reading, imply that standing riders

slid diagonally

across the wave face, this detailed account is notable

for the empirical

data (by noting the rider's motion relative to the compass

points) that

dramatically illustrates that the rider is transversing the

wave face.

Until this

point

the paper has successfully avoided discussing the complex

nature of surfboard

riding mechanics.

Suffice it say,

Blake's histrorical analysis confirming that ancient Hawaiians

rode waves

transversely while standing is correct.

It may be

possible

to extend Blake's argument to more extreme conclusions.

(57)

Blake writes:

"Caton describes these boards as being about one and one-half inches thick, seven feet long, coffin shaped, rounded at the ends, chamfered (beveled) at the edges; about fifteen inches wide at the widest point near the forward end, and eleven inches wide at the back end." (58) page 42

Blake's commentary claims the boards are constructed of koa (Acacia koa) or breadfruit (ulu) (Artocarpus incisus), but is unclear if this is further paraphasing Caton or Blake's conclusion.

"Clearly, boards of the aliea, or thin design, were usually made of koa or wood of the breadfruit tree." (59)

His conclusion, with or with-out confirmation by Caton, is

probably

correct.

His comparison of Caton's alaia with the boards of his day is

difficult

to resile with the performance of contemporary (2007) surfboards.

"At

Waikiki,

today, a board of the above dimensions is used only by

children up to twelve

years old. (60)

Blake notes that Caton (probably for the first time in surfriding literature) raises the question of how surfboards "work" or, more formally, the dynamics of surfboard mechanics.

"Caton found the natives could not explain why they were propelled shoreward with such astonishing speed, nor could Mr. Caton explain it himself, nor could his friends. He hoped that someday, someone would study the question and find an answer to it." (61)

Blake writes

that

"the

answer is relatively simple" (62),

however the opposite

is the more likely case.

There are

several

"simple" difficulties with Blake's analysis.

"Gravity

does

the trick.

The front

slope of the wave on which one slides presents a down-hill

path, while

the friction of the slippery board against the water is

very small." (63)

The friction

on the

board on the water is significant - overwise the board would

sink.

Futhermore the

friction,

or controlled drag, allows the rider to control the board and

maintain

direction.

"It's

the same

as skiing on a snow-covered hill, and there is no doubt as

to what makes

one slide down a hill on skis.

However,

in

skiing, one can start down hill from a stationary

position, while in surfriding

some

momentum

must

first be attained , to catch up with the incoming swell.

This is

accomplished

by paddling the board with the hands and arms." (64)

- Blake(1935)

page 43.

The notion

that the

rider must "catch up with the incoming swell ... by

paddling the board

with the hands and arms" is a common misunderstanding,

even by some

experienced surfriders.

Technically the

wave "catches" the rider.

While the wave

face

("slope") is an essential component of successful

surfriding, the

analysis does not account for wave speed, wave height or the

complex conical

shape of the breaking wave (which is different from a

white-water wave-

"a wave of translation").

Blake does not

explain

the unique dynamics of transversing of the wave face, which he

has previously

established on pages 41 and 42. (65)

6.8

The

next section is of historical interest, its impact stretching

beyond surfboard

design

A discussion of

body surfing technique paraphrases Duke Kahanamoku:

"Duke

Kahanomoku

calls attention to the fact that to catch a wave for "body

surfing," in

the true Hawaiian manner, it is necessary to swim before

the breaker using

the modern crawl stroke, with a flutter kick.

As a boy,

Duke 'body-surfed' and swam the crawl stroke before the

world had a name

for it.

Also the

ancient

Hawaiians, adapt at "body surfing," swam the crawl stroke

as part of the

sport; therefore, the origin of the so-called new crawl

swimming stroke

dates back to antiquity.

The crawl

kick was also used in conjunction with the short

three-foot surfboards

used at Waikiki beach around the 1903 period." (66)

page 43

Essentially,

the

argument proposes a direct relationship between ancient prone

board propulsion

and the 'modern' swimming style identified by swimming

commentators as

the Crawl. (67)

The argument is

a strong one. (68)

Simple

observation

demonstrates the overarm action of board paddling is exactly

the motion

of the Crawl swimming stroke, likewise the 'flutter-kick'

corresponds

directly the method used by prone board riders.

The swimming

stroke

is essential for successful bodysurfing, which undoubtedly

pre-dates European

exploration of the Pacific.

6.9

Blake

quotes from an 1891 article by Dr. Henry Bolton based on

his research,

surfing photography and personal surfriding experience on

Niihau.

Originally

presented

as a lecture with "projections from the original

photographs" in

1890, the text quotes and compares Jarves, Bird and Cummings.

(69)

It is presently

unclear if Blake is directly quoting Boulton, or Boulton

quoting his sources.

"In

1891, Bolton

wrote: 'The sport of surf riding, once so universally

popular, and now

but little seen.'

As seen

on

the Island of Niihau, Bolton describes surf riding:

'Six

stalwart

men assembled on the beach, bearing with them their

precious surfboards.

These

surfboards,

in Hawaiian, 'papahee- nalu,' or 'wave sliding boards,'

are made from the

wood of the veri veri (willi willi), or

breadfruit 'tree.

They are

eight

or nine feet long, fifteen to twenty inches wide, rather

thin, rounded

at each end, and carefully smoothed.

The

boards

are stained black, are frequently rubbed with coconut oil,

and are preserved

with great solicitude, sometimes wrapped in cloths.

Children

use

smaller boards.'

...

Here we

find

the same kind of surfboard, the aliea type used in Niihau,

as seen by Caton

in Hawaii, at the other end of the group of Hawaiian

Islands." (70)

While Blake's

conclusion

that the boards are "aliea type" is correct, note one

of the suitable

timbers for this design is "veri veri" - possibly willi

willi.

If so, this is

in

apparent contradition with Blake's contention:

"An alaia designed board of wili wilIi would not be strong enough" (71)

6.10 Thrum's* article is extensively quoted, cited by Blake as a reliable source:

"In the

'Hawaiian

Annuals', published in 1896, is an account of ancient

surfriding, prepated

by a native of the Kona district of Hawaii, familiar with

the subject.

The

valuable

work was translated by Nakoina, a former surfrider.

I feel

this

to be the finest contribution on old surfriding in

existence and am sure

the 'native from Kona' knew the art of surfriding well." (72)

Following Thrum's* report on staining and oiling of the finished surfboard, Blake quotes Emerson's (or Alexander's) notes to Malo's account of canoe building, but ommits the writer's personal contribution:

"I can vouch for it as an excellent covering for wood." (73)

Blake adds an oral report of a sealing process, apparently not recorded in any surfboard or canoe building context.

"I am

told

by Cottrell (74), who saw the performance, that a

surfboard made

of wili wili wood was buried in mud, near a spring, for a

certain length

of time to give it a high polish.

I should

say

that the mud entered the porous surface of the wilIi wili

board acting

as a good 'filler' for sealing up the surface.

When the

board

was then dried out the mud surface became hard and was

polished and oiled

to a fine waterproof finish." (74)

At first

glance this

seems a practical and relatively easy waterproofing process.

Indeed, a

smooth

surface approaching the finish of the modern fibreglassed

board might be

possible.

However, with

some

reflection the question of 'grip' arises, particularly if the

board was

to be ridden in a standing position.

Surely, before

the

application of parrafin wax circa 1935 (75) a suitable

compromise

between a smooth shape and fine timber grain providing a

suitable friction

with the rider was necessary.

6.11 Unlike this paper, Blake finds only one fault with Thrum's* analysis, the extreme width of "two or three feet wide".

"I can

detect

only one error in the work.

That

writer

says the Olo board of wili wili was 'two or three feet

wide.'

This

makes

the board too wide to paddle comfortably and also too wide

to give a good

performance.

The width

of the Olo board was from one to two feet wide, instead of

from two to

three." (76)

While this objection is valid (see 5.2), the following inference is confusing:

"I also infer, from that error, the writer to be unfamiliar with the wiIi wili, or chief's board." (77)

If Thrum* is "unfamiliar

with

the wili wili, or chief's board", then not "only one"

but

all the details relating to this design are questionable.

It is dificult

to

see how Blake's subsequent conclusions can be supported in

this context,

however he does indicate a contemporary case in conflict with

the general

consensus.

"It is

also

evident from his writing that the Olo, or long thick

board, was not made

of koa and ulu, but of only wili wili.

Therefore,

Paki's

boards of Olo design and made of koa are an exception and

not the

rule.

They

really

are too heavy to please the average surfrider.

On the

other

hand, we have today an enthusiastic and skillful surf

rider, Northrop Castle,

who has a board weighing more than either of Paki's.

Castle's

board

weighs about two hundred pounds, and he likes it." (78)

6.12Blake's next reference is unclear in its source and its importance.

"In the

American

Anthropologist, 1889, ...

Andrews (79)

gives the names Olo and wili wili, for a "very thick

surfboard made of

wili wili," and o-ni-ni as a "kind of surfboard," also

"pa-ha" as a name

for a surfboard.

In

Andrew's

mind there evidently was established the belief that the

wili wili wood

was the accepted wood for making the Olo or long thick

surfboard." (80)

If the

reference

is the Hawaiian Dictionary of 1880, then the entries are

probably sourced

from any number of the earlier accounts of surfriding.

It is unlikely

Andrews

devoted a great deal of thought in determining the timber

suitable for

Olo construction.

Similarly,

Blake

quotes Brigham (5.1) to support his thesis. (81)

As previously

discussed

(5.1), only Brigham's description of the common surfboard is

based on observation

and the notes on the Olo and on reported dimensions are likely

drawn from

Malo.

Blake's

conclusion

overstates the case.

"There again, we have an entirely different writer, who actually says that the Olo, or narrow board, was made of the light wili wilIi wood and up to eighteen feet in length." (82)

6.13 Hawaiian Surfboard has a selection of photographs, the third set between pages 48 and 49, includes Jacques Arago's (engraving by Alphonse Pellion) :"The Houses of Kraimokou, circa 1819" with a caption by Blake (83), discussed in 3.7 above.

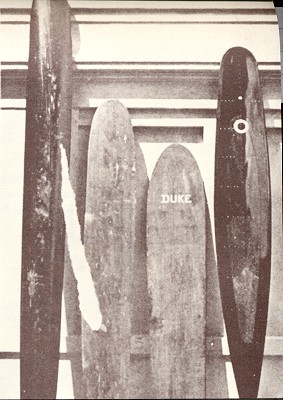

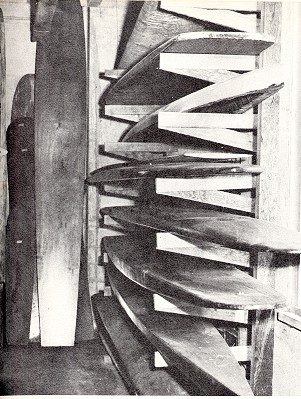

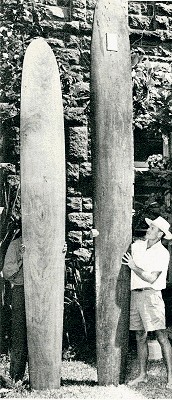

| This

third set also

includes a photograph of a selection of four

surfboards, image right.

Unfortunately the printed image crops the tails of all the boards and the nose of Paki's board. The white scar on the left appears to be damage to the page in the book from which this 1983 edition was copied. (84) Although

only two

of the boads are ancient, the comparsion between the

relative weights of

the boards is informative.

|

|

6.14

In

Chapter 4, "Modern surfriding", on page 59, Blake returns

to the

subject of ancient surfboards as previously promised, see 6.2

above. (86)

Quoting from one of his previously

published

magazine article (87), Blake

writes of his

recreation and testing the ancient olo design.

"In

another

magazine, 'The Pan Pacific', an article called 'Surf-

riding- The Royal

and Ancient Sport', by this writer, discloses the motif (sic?)

for trying to change the then popular and satisfactory

type of surfboards.

Written

in

1930, the article reads in part:

'Strange

as

it may seem, three old-style Hawaiian surfboards of huge

dimensions and

weight have hung on the walls of the Bishop Museum -in

Honolulu for twenty

years or more without anyone doing more than wonder how in

the world these

great boards were used, and were they not too long and

heavy to be practicable;'".

"I too,

wondered

about these boards in the museum, wondered so much that in

1926 I built

a duplicate of them as an experiment, my object being to

find not a better

board, but to find a faster board to use in the annual and

popular surfboard

paddling races held in Southern California each summer.

This

surfboard

was sixteen feet long and weight 120 pounds" (88)Page

59.

After detailing the success of the board in paddling races, a significant wave riding characteristic of the design is noted.

"What

pleases

me most is the way the board can catch the ground swells

on the reef so

much farther out to sea than the ordinary surfboard.

So my

faith

in the ideas of the old Hawaiians has been rewarded by the

performance

of a board designed by them thousands of years ago." (88)

Page 59-60

Blake had

shown that

boards of ancient olo dimensions did have a practical use,

specifically

riding waves with a gentle sloping face.

For the next

twenty

years Tom Blake's hollow board, derived from these

experiments, was a world

wide popular alternative to the solid wood board (which

closely resembled

the ancient alaia). (90)

An (obsure)

reference

dates the last of the olo riders as around the turn of the

century.

"I have

some

notes relative to the 1900 period written by Wm. A.

Cottrell (91),

one of the early surfriders at Waikiki.

He says:

"Princess

Kaiulaini was an expert surf rider around 1895 to 1900.

She rode

a

long Olo board made of wiIi wili.

She

apparently

was the last of the old school at Waikiki.' " (92) Page 60

Reprinted in

1983

by Bank Wright as

Blake, Tom: Hawaiian

Surfriders

1935

Mountain and

Sea

Publishing, Box 126 Redondo Beach California 90277 1983

Embossed hard

cover

with adhesive image.

DeLa Vega

(2004) notes "Joel Smith's edition was used to create

these plates.",

page 38.

2. "Blake's

work

has been extensively quoted by many subsequent surfing

historians

and journalists."

To detail a

complete

inventory would be pointless - almost every surfing book or

surfing magazine

article that discusses ancient Hawaiian surfing either quotes

Blake directly

or his sources.

The following

works,

excluding those of Ben Finney detailed below, are readily

available.

Nat, Warshaw,

Lueras,

Carroll,

Also Lynch:

Blake

1, 2 & 3.

3. Ben

Finney

originally prepared his research for a masters thesis in

anthropology.

The quality of

his

work has set the benhmark for all following historians of

surfriding.

Finney, Ben: Surfing

in

Ancient Hawaii

The Journal

of

Polynesian Society

December 1959

Volume

68 Number 4 pages 327 - .347.

Finney, Ben: The

Development

and Diffusion of Modern Surfing

The Journal

of

Polynesian Society

December

1960

Volume 69 Number 4 pages 314 - .331

Finney, Ben

and Houston,

James D. : Surfing – The Sport of Hawaiian Kings

Charles

E.

Tuttle Company Inc.

Rutland,

Vermont

and Tokyo, Japan. 1966.

Second printing

196?, Third printing 1971.

Finney, Ben

and Houston,

James D. : Surfing – A History of the Ancient Hawaiian

Sport

Pomegranate

Books

P.O. Box

6099

Rohnert Park, CA 94927. 1996

Soft

cover,

117 pages, 20 b/w photographs, 24 b/w illustrations,

Appendices,

Notes, Bibliography.

4. Blake,

Tom:

Hawaiian Surfriding

Nothland

Press,

Flagstaff,Arizona, 1961

Soft cover, 41

pages

- without page numbers.

5. Lynch,

Gary

and Gault-Williams, Malcom:

Tom Blake :

The

Uncommon Journey of a Pioneer Waterman

Published

by the Croul Family Foundation

Corona

del

Mar, California. 2001. Page ?

6. Note Thrum's native reporter as the one possible example, but untestable.

7. Blake contest record

8. Blake pages ?

9. Lynch and Gault-Williams: Op. cit., Chapter 1

10. Lynch and Gault Williams, clipps files

11. The above books, plus a series of design articles in magazines, almost certainly with Blake's input.

12. National geographic 1935.

13. "a

commericial interest" , apart from the possible

financial benefits

of publication.

Most authors

hope

for some financial return from their work, even if sales only

indicate

a public interest.

The publishers

of

the various surfriding articles in Hawaiian newspapers, which

are unfortunately

not available for this paper, possibly had some commercial

interest in

promoting Hawaii as a tourist destination.

In Blake's case, it appears the financial rewards from The

Hawaiian

Surfboard were not great.

The initial printing was hard cover with a dust jacket, followed

by

an imprinted cloth cover (probaly original without the dust

jacket) and

two editions in tapa cloth dust jackets..

Lynch and

Gault

Williams, pages?

14. This is

indicated

with Chapter 4 of HS.

Also see

Lynch

and Gault Williams, pages?

Garry Lynch

interviewed

Tom Blake in at Washburn, Wisconsin, on 16th April 1989.

Blake's

comments

included this assessment of the success of his commerical

surfboard building

ventures:

"And I never did make any money on it.

When royalties would mount up to thirty-forty dollars, or

maybe a hundred, I'd take out a few boards and use them for

myself, or

give them to friends.

That's the way it was then."

Garry Lynch: Tom

Blake

Interview, Washburn, Wisconsin,16th April 1989.

Notes forwarded

by Garry Lynch, with many thanks, by email, April 2007.

15. Sleding, qualifies. see Buck and Finney?

16.

European royal

sports Falcons, Hounds, Yatching, ???

In Japan,

there were even strict restrictions on who could hunt

which sorts of animals

and where, based on rank within the samurai class

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Falconry

17. Lynch and Gault Williams

18. The

emphasis

on scripture by Protestant missionaries saw the rapid

development of a

written Hawaiian language to provide translated Biblical

texts.

By the late

1800s,

the written Hawaiian language had expanded into cultural and

commerical

life.

Isabella L.

Bird

reported in 1873:

"There are

four

newspapers: the Honolulu Gazette, the Pacific Commercial

Adverttser, Ka

Nupepa Kuokoa (the ''Independent Press "), and a lately

started spasmodic

sheet, partly in English and partly in Hawaiian, the Nuhou

(News)."

Bird,

Isabella

L.: Six Months in the Sandwich Isles

John Murray,

London,

1875. Pages 179.

DelaVega notes numerous articles.

19. This would be an interesting exercise, unfortunately I currently do not have access to the original articles.

20. Blake (1935): Op. cit., Page 37.

21. In

response

to an inquiry as to whether Tom Blake could read Hawaiian,

Garry Lynch

replied:

"Tom

only

knew a few Hawaiian words and phrases.

He was

constantly

in touch with the people at the Bishop and all others who

had information

and could translate any information that was out there.

He knew most

of the scholars at the time."

Garry Lynch: email correspondence, April 2007.

With thanks for the contribution.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

16. Fornander,

Abraham:

Forlander Collection of Antiquities and Hawaiian Folk Lore

: Translations by Thomas G. Thrum.

Bishop Museum

Press,

Honolulu, 1919-1920.

Memoirs of the

Bernice

Pauahi Bishop Museum, Volumes 4, 5 and 6.

DeLa Vega

(2004) notes "Tom Blake considered this collection one of

the most comprehensive

looks at the legends and chants of ancient Hawaii.",

page 19.

Unfortunately,

Blake's

quotation is the only copy of this report currently located

for this paper.

Blake: Op.

cit.,

Page 16

.

The quotation,

fully

discussed at 5.9, is:

'Here are

the

names of that board and the surfs.

The board is

alaia, three yards long.

The surf is

kakala,

a curling wave, terrible, death dealing.

The board is

Olo, six yards long.

The surf is

opuu,

a non-breaking wave, something like calmness."

17. Blake: Op. Cit., Page 16.

18.Blake: Op. Cit., Page 16.

19. Ellis: Op.Cit.,

20. Blake: Op. Cit., Page 16.

21. Blake: Op. Cit., Page 16.

22. Drift logs!!!

23. Blake: Op. Cit., Pages 16-17.

24. Thrum:

Op.

Cit.,

Finney and

Houston:

Op. Cit., Page 102.?

25. Blake: Op. Cit., Page 17.

26. Blake:

Op. Cit., Page 17.

37. I

am unable

to identify the published source of this quotation.

It is

obviously

an edited and rewitten version of King, as edited by Douglas,

see 2.7.

The source is

possibly

(as suggested by Blake) is a history of the voyage

written by "Ellis"

and published in 1783, the original report (or reports)

certainly dated

1778-1779.

It may be an

official

publication, hurried into print to maximise sales.

The report

cleary

is not a first person account and is basically

King/Douglas.

It has not been

considered previously as a reputable report.

Blake's quoted

text

reads

"Native men,

and women alike, enjoyed it.

In

Kealakakua

Bay (Hawaii) the waves broke out about one hundred and fifty

yards.

Twenty or

thirty

natives, each with a narrow board with rounded ends, would

start out together

from the shore and battle the breaking waves to a point out

beyond.

The surfers

would

then lay themselves full length upon the boards and prepare

for the swift

return to shore, They would throw themselves in the crest of

the largest

wave, and be driven towards shore with amazing rapidity.

The riders

must

ride through jagged opening in the rocks, and, in case of

failure, be dashed

against them."

38. Blake: Op. Cit., Page 30.

39.Archibald

Campbell,

in his work, Voyage Around the World, 1806-1812"

"They often

swam

several miles offshore, to ships, sometimes resting upon a

plank shaped

like an anchor stock -and paddling with their hands, but

more frequently

without any assistance what- ever. Although sharks are

numerous in those

waters, I never heard of any accident from them, which, I

attribute to

the dexter- ity with which they avoided their attacks."

40. Ellis,

Rev.

William: Polynesian Researches, During a Residence of

Nearly Eight

Years in the

Society and

Sandwich

Islands, Volumes I to IV..

Fisher, Son and

Jackson, London, 1831. Pages 368 to 372.

Reproduced in

Finney, Ben and

Houston, James D.: Surfing – A History of the Ancient

Hawaiian Sport.

1996.

Appendix C.

Pages

98 to 99.

Blake's

(edited)

quoted text reads:

"There are

few

children who are not taken into the sea by their mothers the

second or

third day after their birth, and many can swim as soon as

they can walk."

I can say

that

many children, boys of about eight years old, can ride the

waves on a surfboard.

True, they stay near shore, but master the same technique as

their older

brothers.

The great

regard

of the ancient Hawaiian for his surfboard, displayed by his

care in drying

and oiling it and even wrapping it in tapa and hanging it in

his house,

gives some idea of the value and high place the surfboard

had in his life."

41. Ellis: Op.Cit.,

42. Blake: Op. Cit., Page 30.

43. Malo, Op. Cit.,

44. Blake: Op. Cit., Page 30.

45. Blake: Op. Cit., Page 30.

46. Blake: Op. Cit., Page 30.

47. Lynch and Gault-Williams: Op. Cit., Page

48. Tom

Blake

is often credited with many notable achievements - the hollow

board, the

water-proof camera housing, the torpedo buoy, and others.

His work on the

ancient boards of the Bishop Museum definitely qualifies him

as the "Father

of surfboard restorers".

49. Blake: Op. cit., Pages 37 - 38.

51. Lyman,

Chester

S. (1814-1890): Around The Horn To The Sandwich Islands

And

California 1845

-1850.

New Haven: Yale

University Press 1924) Chapter II, page 73.

Travel diary in

1846 notes.

Quoted in

DelaVega

(ed, 2004): Op. cit., page 22

51. Lyman:

Op

Cit., Travel diary in 1846 notes. Chapter II, page 73.

Quoted in

DelaVega

(ed, 2004): Op. cit., page 22

52. Lyman:

Op

Cit., Travel diary in 1846 notes. Chapter II, page 73.

Quoted in

DelaVega

(ed, 2004): Op. cit., page 22

53. Gault Williams: Op. cit., page 181.

54. Gault

Williams: Op. cit., page 181.

The reference

in

I'i is

page?

55.

Finney

and Houston : 1996. Pages

Reproduced in

Gault Williams:

Op. cit., Pages 55 to 62.

56. Blake: Op. cit., Page 42.

57. Also tubed, certainly prone. Rode large waves.

58. Blake: Op. cit., Page 42.

59. Blake: Op. cit., Page 42.

60. Blake: Op. cit., Page 42.

61.Blake: Op. cit., Page 42.

62.Blake: Op. cit., Page 42.

63.Blake: Op. cit., Pages 42- and 43.

64.Blake: Op. cit., Page 43.

65. see Surfboards Dynamics

66. Blake: Op. cit., Page 43.

67. There is some dispute amoung swimming commentators as to the origin of the Crawl as illustrated by the commonly used alternatives: 'the American Crawl' or 'the Australian Crawl'.

68. List alternative claiments.

Note Polynesian connection to Australia,

69. DelaVega (ed, 2004): Op. cit., page 12

70. Blake: Op. cit., Page 44.

71. Blake: Op. Cit., Page 16.

73. Malo: Op. Cit., Pages 133 and 134.?

74. Blake:

Op. Cit., Pages 45 and 46.

No idea who

Cottrell

is.

75. A

claim

for the first use of parrafin wax was made by Alfred E Gallant

(Letters,

Longboard

Magazine, USA, 1999).

Post 1935, he

noticed

the grip of his damp feet after his mother recently applied

floor wax.

She then

advised

use of paraffin sealing wax for his surboard.

76.Blake: Op. cit., Page 47.

77.Blake: Op. cit., Page 47.

78.Blake: Op. cit., Page 47.

79.

Andrews,

Noted in

dela

Vega

80.Blake: Op. cit., Page 48.

81.

Blake's

quotation reads

"Brigham, in

Preliminary Catalogue, says: 'Surfboards were usually made

of koa, flat

with a slightly convex surface, rounded at one end, slightly

narrowing

towards the stern, where it was cut square.

Sometimes,

the

'pa-pa' (surfboard) was made of a very light wi Ii wili and

then made;ooQ1Q.

(narrow).

In size,

they

varied from three to eighteen feet in length and from eight

to ten inches

in breadth, but some of the ancient boards were said to have

been four

fathoms long."

Blake: Op.

cit.,

Page 48.

82. Blake: Op. cit., Page 48.

83. Blake's

caption

reads

" ...the

surfboard

of wili wili wood was reserved for the Chiefs. ..

The oldest

picture

of a surfboard in existence.

From a

drawing

by a French artist Pellion in 1819.

The man in

the

picture is evidently a Hawaiian Chief because of his helmet

and feather

cape.

The woman in

the picture is pounding tapa of which they fashioned their

simple clothes.

The great

size

of the surfboard lying in the yard is in keeping with Chief

Paki's museum

boards. -Photo by Baker "

Blake: Op.

cit.,

Illustrations, Third set, between pages 48 and 49, Plate 4.

84. Blake:

Op. cit., Illustrations, Third set, between pages 48 and

49, Plate

? ,

For 1983

publishing

details, see Endnote 1 above.

85.

86.

87.

88.Page

59-60

89. Possibly

Knute

Cottrell, a comtemporary of Duke Kahanamoku and a founding

member

of the Hui Nalu

club, circa

1908.

90. Page

60

ordinary

surfboard.

So my faith in the ideas of the old Hawaiians has been

rewarded by the

performance of a board designed by them thousands of years

ago.

"Dad Center,

kamaina and famous surf rider, says that when he was a boy

on the Island

of Maui, a native took a long board out in storm surf and

rode the swells

till they broke near shore. So there we have a complete

substantiation

of what the museum type board suggests. Dad continues, 'That

was in the

'90's and was about the finish of the long board on that

island. They were

occasionally used, however, more as a novelty at Waikiki,

until around

1900.

I "Around

1900

the art of surfriding was almost obsolete. Even at Waikiki

beach there

was very little as most people lived in Honolulu and it was

difficult to

get to Waikiki. Interest revived and in 1907 a group of

prominent men,

led by Alexander Hume Ford, organized and formed the

Outrif{ger Canoe Club.

The

charter

reads:

'We wish to have a place where surfboard riding' may be

revived and those

who live away from the water front

may keep

their

surfboards. The main. object of this club being. to give an

added and permanent

attraction to Hawaii and make

the Wajkiki

beach

the home of the surfrider'."

I have some

notes

relative to the 1900 period written by Wm. A. Cottrell, one

of the early

surfriders at Waikiki.

Possibly

Knute

Cottrell, a comtempoary of Duke Kahanamoku, and founding

member of

the Hui Nalu club, circa 1908.

He says:

"Princess

Kaiulaini was an expert surf rider around 1895 to 1900. She

rode a long

010 board made of wi Ii wili. She apparently was the last of

the old school

at Waikiki.

"About 1903

we

used a short board a few feet long, rather thin and wide,

like a washboard.

From 1903 to 1908 marks the true revival of the sport.

encouraged by the

following old timers: Wm. Dole, Dudie ¥iller. Duke

Kahanamoku, Harold

Castle, Geo. Freeth. Dad Center, Kauha, Ho1stein, Jordan,

Lishman, Atkin-.

son, "Steamboat" Bill, Winter, Brown. Kaupipko, Mahelona,

Kea- wamaki,

May, Curtiss, Hustace, Roth, Aurnolu and McKenzie. Some of

these men are

riding today. Many of the above men were members of ,the

first club, called

the 'Waikiki Swimming Club'; the charter members were Duke

Kahanamoku,

Knute Cot- rell, and Ken Winters. This club was an incentive

which influenced

the foundation of the Outrigger Canoe Club in 1907 and the

Hui Nalu along

about the same time."

Page 60.

Reprinted in

1983

by Bank Wright as

Blake, Tom: Hawaiian

Surfriders

1935

Mountain and

Sea

Publishing, Box 126 Redondo Beach California 90277 1983

Embossed hard

cover

with adhesive image.

DeLa Vega

(2004) notes "Joel Smith's edition was used to create

these plates.",

page 38.

2. Blake,

Tom:

Hawaiian Surfriding

Nothland

Press,

Flagstaff,Arizona, 1961

Soft cover, 41

pages

(without page numbers), 58 black and white plates, 3 black and

white ???

3. Blake's

work

has been extensively quoted by many subsequent surfing

historians.

To detail a

complete

inventory would be pointless - almost every book or magazine

article that

discusses ancient Hawaiian surfing either quotes Blake

directly or his

sources.

The following

works

(excluding those of Ben Finney) are readily available.

Nat, Warshaw,

Lueras,

Carroll,

4. Ben

Finney

originally prepared his research for a masters thesis in

anthropology.

The quality of

his

work has set the benhmark for all following historians of

surfriding.

Finney, Ben: Surfing

in

Ancient Hawaii

The Journal

of

Polynesian Society

December 1959

Volume

68 Number 4 pages 327 - .347

Finney, Ben: The

Development

and Diffusion of Modern Surfing

The Journal

of

Polynesian Society

December

1960

Volume 69 Number 4 pages 314 - .331

Finney, Ben

and Houston,

James D. : Surfing – The Sport of Hawaiian Kings

Charles

E.

Tuttle Company Inc.

Rutland,

Vermont

and Tokyo, Japan. 1966.

Second printing

196?, Third printing 1971.

Finney, Ben

and Houston,

James D. : Surfing – A History of the Ancient Hawaiian

Sport

Pomegranate

Books

P.O. Box

6099

Rohnert Park, CA 94927

Soft

cover,

117 pages, 20 b/w photographs, 24 b/w illustrations,

Appendices,

Notes, Bibliography.

5. All

reproduced

text is in Bell 14 point and not in quotation marks or

italics.

My text is in

Arial

12 point.

For screen

clarity,

the reproduced text and my own work has been adjusted to my

standard online

format.

Paragraphs are

indicated

by a spaced line (replacing indentation) and each sentence

takes a new

line.

Page 17

1. Fornander,

Abraham:

Forlander Collection of Antiquities and Hawaiian Folk Lore

: Translations by Thomas G. Thrum.

Bishop Museum

Press,

Honolulu, 1919-1920.

Memoirs of the

Bernice

Pauahi Bishop Museum, Volumes 4, 5 and 6.

DeLa Vega

(2004) notes "Tom Blake considered this collection one of

the most comprehensive

looks at the legends and chants of ancient Hawaii.",

page 19.

2. "alaia,

three yards long"

One yard equals

three feet, 36 inches or 92 cm.

The reported

alaia

is approximately 9 feet or 275 cm long.

This conforms

with

existing examples of the board.

3. "kakala,

a curling wave, terrible, death dealing."

The wave is

characterised

by its steep face and hard breaking curl.

It is typically

found in the common beach break.

4. "Olo,

six yards long."

One yard equals

three feet, 36 inches or 92 cm.

The reported

Olo

is approximately 18 feet or 550 cm long.

This reasonably

conforms with two know existing examples of the board, hower

both are in

koa wood..

5. "opuu,

a non-breaking wave, something like calmness."

The wave is

characterised

by its gentle sloping face.

A noted feature

of surfing conditions at Waikiki, Ohau, it is favoured by

canoe surfers.

6. "This

passage

shows the different boards best suited to different kinds of

waves."

Although this

is

generally correct, the performance of any surfboard is a

function of the

rider's statue and skill.

7. "The

alaia

as the thin board was called, ranged from a few feet, a

child's size,

to about twelve feet long for adults."

Buck (1959)

notes

"The Bishop Museum collection consists of 25 boards ranging

from

a child's board of breadfruit wood (Bishop Museum

catalogue number

C. 5966), 34.25 inches long, weighing 2 pounds 10 ounces to

a modern

redwood board, 17 feet 2 inches long, weighing 174 pounds."

Page 384.

While Blake

chiefly

characterises the alaia as "the thin board" with a

wide range of

lengths and widths,

Buck

(1957) and Finney (1959) make a

distinction based on riding position - prone

("body-board') or standing

models ("true surfboards"), based largely on length.

Buck (1957)

page

384

Finney

(1959)

pages 331 and 333.

This

distinction

presents several difficulties.

1. Firstly, it

requires

the observer to determine the riding position of any

particular board based

on their surf riding experience.

As noted above,

the performance of any surfboard is a function of the rider's

statue and

skill.

2. While early

reports

indicate that solid board riders did ride in the standing

position, it

is unclear if this was practised as an exclusive preference.

The ancients

may

have ridden a particular wave in a variety of positions -

prone, kneeling,

drop-knee, sitting and standing - adjusting to changes in the

wave's shape

and velocity.

3. There is no

such

distinction in the early literature.

Commentators,

such

as Malcom Gault-Williams (2005) have used the term paipo

(page 95) to indicate prone boards, but this word does not

appear in any

list of ancient Hawaiian words.

See Finney

and

Houston (1996) Appendix A, pages 94 to 96.

4. The

principal

feature for a board to be ridden in a standing position is

possibly the

width.

5. All these

commentators

fail to note the major advantage of a board with larger volume

- a significant

improvement in padding speed and distance.

It is probably

reasonable

to assume that, regardless of the statue and skill of the

rider, that smaller

boards were mostly used at surfing breaks close to shore,

while larger

boards had the potential to ride waves breaking a

considerable distance

from shore.

8. "The

larger

one being about one and one half inches thick through the

center, levelling

off on both top and bottom to about one-quarter inch at the

edges."

This indicates

that

the maximum thickness for the alaia was one and one half

inches, considerably

thinner than all subsequent surfboard designs.

9. "The

kakala,

indicates a wave that steepens up and crashes over the

shallow coral."

As noted, this

type

of wave is typically found in the common beach break.

Surfing breaks

occuring

on coral reefs are generally limted to equatorial regions.

10. "koa" (Acacia

koa)

Tommy Holmes'

authorative

work, The Hawaiian Canoe (1981, 1993), writes

extensively about

koa and its use of by ancient Hawaiian canoe builders.

Significant

sections

are of interest in a discussion of ancient Hawaiian

surfboards.

Holme's work is

fully referenced, however his notes are not included in this

paper.

Holmes, Tommy :

The

Hawaiian Canoe - Second Edition

Editions

Limited,

PO Box 10558 Honolulu, Hawaii 96816.

First Edition

1981.

Second Edition 1993. Second Printing 1996.

Koa

A

magnificent and totally unexpected gift awaited discovery by

the settlers

reaching Hawai'i.

The

islands

were blessed with extensive forests of what would come to be

called

koa, trees of extraordinary size that were found nowhere

else in the world.

These

trees

would provide wood of remarkable durability out of which the

Hawaiian

would shape his canoes.

For

some

1500 years the Hawaiian people lived in delicate balance

with their

environment, the trees they used being replaced by natural

regeneration.

Contact

with

the west shattered this fragile balance; in the span of a

few decades

koa began a radical decline that has continued even to the

present day.

"Their

huge trunks and limbs cover the ground so thickly that it is

difficult

to ride through the forest, if such it can be called,"

writes E.F. Rock

in 1913 of a once beautiful koa forest in Kealakekua, South

Kona.

Rock,

a

botanist, goes on to note of this macabre forest scene that

"90 per cent

of the trees are now dead, and the remaining 10 per cent in

a dying condition."

In

1779,

a little over one hundred and thirty years before Rock's

observations,

Lt. Charles Clerke who was with Captain Cook tells of

wandering through

the koa forest above Kealakekua: "Some of our Ex- plorers in

the woods

measured a tree 19 feet in the girth and rising very

proportionably [sic]

in its bulk to a great height, nor did this far, if at all,

exceed in stateliness

many of its neighbours; we never before met with this kind

of wood."

Similarly,

Archibald

Menzies in 1792 describes the same area: "The largest trees

which

compose this vast forest I now found to be a new species of

mimosa [koa].

..I measured two of them near our path one of which was

seventeen feet

and the other about eighteen feet in circumference, with

straight trunks

forty or fifty feet high. ..as we advanced, the wood was

more crowded with

these trees than lower down where both sides of the path had

been thinned

of them by the inhabitants."

Page

Acacia

koa, once undisputed monarch of the forests of Hawai'i,

probably evolved

from seeds hitchhiking to Hawai'i in the bowels of some

storm-blown bird

or through some other capricious act of the winds and seas.

In

an

environment that was comparatively free of competitors and

predators,

koa proliferated to where it was once-after 'ohi'a- the

second most common

forest tree in Hawai'i.

It

has

been estimated that today there is standing probably not

much more

than ten percent of the amount of koa that existed at the

time of Cook's

arrival; presently non-native species make up the majority

of the forests

of Hawai'i.

Page

Koa

sometimes reaches massive proportions.

Tall,

straight

koa trees up to 20 feet in circumference were seen by a

number

of Europeans visiting Hawai'i in the late 1700's and early

1800's.

One

legend

reputes a koa tree with a straight trunk as high as 120

feet, and

Emerson notes ten men were required to encompass another

mammoth koa tree

from

which a canoe was to be hewed. Though these dimensions are

probably exaggerated,

there undoubtedly were some quite large koa trees.

Straight

trunks

in excess of 70 feet were not unheard of; and while never

plentiful,

one can still find today an occasional 50- t060-foot

straight-trunked koa

tree.

In

1977

a 62-foot log was felled in the Honomalino forest above

Kona, from

which a ten-man, 58-foot canoe has been made.

Of

old,

certain areas such as the mountains above Hilo and Kona and

the slopes

of Haleakala produced such an abundance of high quality

canoe logs that

a very disproportionate amount of the total number of canoes

throughout

the islands came from these sites.

At

Keauhou

Ranch on the island of Hawai'i there stands what is

considered

to be the largest koa tree in the world. Its trunk measures

some 12 feet

in diameter and 371/2 feet in circumference.

Though

the

trunk only rises about 30 feet before branching, its topmost

branches

tower 140 feet above the ground.

The

tree

is probably four hundred to five hundred years old.

Page

Koa

For Canoes

Early

Hawaiians,

and canoe builders in particular, possessed an especially

detailed

knowledge of differing physical characteristics of woods,

primarily of

Acacia koa.

In

the

absence of modern-day botanical classification techniques,

the canoe

builder devised his own very sophisticated system for

classifying koa.

Through

analysis

of a tree's trunk shape and dimensions, bark, grain, and

branching

patterns, a canoe builder was able to identify each koa tree

as being of

a certain type.

Beyond

the obvious gross physical characteristics of a koa tree,

the ancient canoe

builder was most concerned with the grain, for well he knew

that each tree

possessed distinct grain characteristics. While today's

botanist will tell

you that Acacia koa is Acacia koa, he will observe that

there is, besides

the more obvious differences in physical characteristics, a

remarkable

range in the density from one tree to the next, and from one

stand to the

next.

The

density

of koa ranges from a low of about 30 pounds per cubic foot

to a

high of 80 pounds per cubic foot.

In

some

cases there will even be a significant range of grain

density within

the same tree.

It

was

apparently this maverick and obscure feature of koa wood

that most

plagued the canoe builder.

Page 29

While

the Hawaiian did not think in terms of pounds per cubic

foot, he did develop

a system of grain classification that was for all practical

purposes comparable

to a botanist's grain density scale.

Low

density

koa (roughly 30 to 45 pounds per cubic foot) was to the

canoe builder

generally soft, lightweight, and yellowish.

He

called

it koa la' au mai' a (banana- colored koa) and valued it for

its

lightness as wood for paddles, but rarely used it for

canoes.

Another

name

for this type of koa wood was koa' awapuhi, literally,

"ginger koa,"

which was regarded as female by the Hawaiians.

Mid-range

density

koa (40 to 60 pounds per cubic foot), reddish to brown, was

overwhelmingly

favored for making canoes, primarily because of its

durability, and strength-to-weight

relationship. Koa at the high end of the density range (60

to 80 pounds

per cubic foot) was almost black in color and extremely

heavy.

The

wood

of this type of tree was called koa 'i'o 'ohi'a (hard

'ohi'a-like

grain) and was usually avoided for canoes because the wood

was heavy and

hard to work.

On

the

occasion when a canoe was made of this kind of koa it was

said that

it "will never lose its heaviness until. it is smashed."

This

contrasts

to the typical koa canoe that over the years loses weight

due

to water loss from the wood.

Noting

the

tendency of koa to crack and check, canoe builder Z.P.K.

Kalokuokamaile

said that the canoe maker of old had "to be very careful for

the grain

of some trees lie [sic] all in the same direction."

(Note that one

would

expect "the tendency for koa to crack and check" to be

an important

concern to the builder using this timber for surfboards, it is

not mentioneed

in any of the traditional sources.)

Further

identification of a tree was made through its bark.

Unfortunately,

only

two types are recorded.

Kaekae

was

a whitish bark that generally covered a tall, handsome tree,

indicating

a straight grain of the la' au mai' a variety.

This

type

of tree, according to Kalokuokamaile, made "a very light

canoe and

floats well after it is built and put into the sea."

Maua

on

the other hand, was a dark red bark that typically sheathed

the tough,

heavy, black-grained ~i'o 'ohi'a, of which "the grain of the

wood twists

forward and back.

This

is

hard to make into a canoe."

Trunk

shape

and dimensions, and branching patterns provided the canoe

builder

with his most common means of identifying different types of

koa.

Holmes then

records

a list of twenty-one terms still known that were used in

identifying koa

wa'a (koa for canoes).

Page 30

10. "breadfruit tree."(ulu) (Artocarpus incisus)

11. "wili wilIi wood" (Erythrina sandwicensis)

In a section titled Other Woods, Holmes discusses the use of breadfruit and willi willi in canoe building.

Fornander

notes that besides koa, "three other kinds of wood were used

in the olden

time for building canoes, the wiliwili, kukui (candle-nut

tree), and ulu

(breadfruit tree).

The

wiliwili

is yet being used.

The

kukui

is not much seen at this time.

The

ulu

is used for repairing a broken canoe

"

Handy comments that the early Hawaiian settlers found kukui

"to be one

of their most valuable assets, perhaps the chief of which

lay in the fact

that the trunks of large trees could be hollowed into superb

canoe hulls."

Soft,

light

and easily worked, breadfruit, kukui and wiliwili were

especially

favored as play or training canoes particularly for young

aspiring canoeists

or women.

The

"baby"

or training canoes rarely exceeded 20 feet in length and

usually

were in the 10 to 15 foot range.

Of

the

light woods, breadfruit was apparently least used; not only

was the

breadfruit tree fairly rare and needed as a food source, the

one variety

available to the Hawaiians was usually unsuitable in girth

and height for

making canoes.

Holmes'

comments

probably account for the restricted use of breadfruit for

surfboard building,

certainly for larger boards.

Of

wiliwili,

Fornander notes that "it was also made into canoes, provided

a tree large enough to be made into a canoe can be found;

but it is not

suitable for two or three people, for it might sink in the

sea.

But

it

must not be finished into a canoe while it is green; leave

it for finishing

till it has seasoned, then use it."

The essential

requirement

that the timber be seasoned before finishing is not reported

in any of

the accounts of early surfboard construction.

Emerson

says

of softwood wiliwili canoes that: "If not sufficiently

durable and

resistant to the powerful jaws of the shark, they were at

least easily

manipulated and very buoyant, and made a cheap and on the

whole a very

serviceable canoe for ordinary purposes."

Degener,

in

his book Flora Hawaiiensis, noted that in the early

part of this

century canoes of wiliwili were not in "favor because of the

belief that

sharks preferred to follow this particular wood." The

limited literature