|

surfresearch.com.au

renwick : okinuee, 1957 |

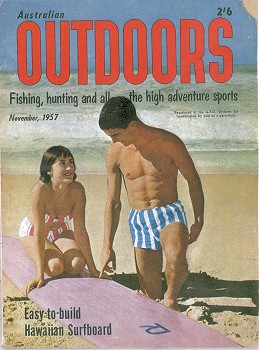

Renwick, Ross: Build yourself an okinuee board.

Australian Outdoors

November, 1957, pages 16 to 21.

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

surfresearch.com.au

renwick : okinuee, 1957 |

Build

yourself an okinuee board

They're

all the rage this surfing season!

The

Hawaiians introduced them to Australia last year, and they

caught on fast.

They're

easy to make, too!

It was late

on

the afternoon of Sunday, November 10, last year, at Avalon

Beach in N.S.W.

An international

surf carnival had just drawn to a fairly drab finish, with

teams from America,

South Africa, New Zealand; Ceylon, Hawaii and Australia

competing.

Most of the

crowd

had left.

A few

stalwarts

stayed to watch the Hawaiians take their peculiar little

surfboards out

through the mountainous seas.

The boards

were

short - 6 ft. shorter than our own 16 ft. boards; and they

were wider -

25", compared to 19" or 20".

Instead of

being

made of hollow plywood construction they were carved from

solid female

balsa.

Over the balsa was a thin fibreglass coating.

Opposed to

our

finless 16 ft. boards they had nine inch fins placed about

two inches from

the tail.

These fins were very similar in shape to the dorsal fin of a

shark.

They were as

different from the popular Australian surfboard as they

possibly could

be.

All who

watched

were sceptical.

Earlier they

had seen crack Hawaiian waterman, Tommy Zahn, reputed to be

a former beau

of Marilyn Monroe, compete disastrously in the surfboard

race.

Zahn was

winner

of a 26-mile board race in Hawaii and was paddling the same

board in the

race at Avalon.

It was 15

ft.

long and similar in shape to one of our racing skis.

Over its

frame

of balsa was stretched light canvas which was impregnated

with fibreglass.

A rudder,

operated

with the feet from the lying position, steered it.

Zahn, a

tremendous

figure of a man, paddled out through the 15 ft. sea lying

down.

Rounding the

buoys and back into the wave area, he lay fifth in a field

of top Sydney

board paddlers. On the front of a big wave the nose of his

board dug in

and he disappeared into the break.

When he

surfaced

his board was smashed beyond repair, slit from end to end.

Amused

Australians,

confident of their own surfting prowess, and fed on the

legend of small,

rolling surfs at Waikiki Beach, nodded condescendingly and

said, "Knew

these boys couldn't handle our big, steep waves".

Avalon had

really

turned it on that day.

A surfboat

guarding

the swimming buoys, and supposedly 150 yards outside the

danger area, had

been hit by a huge wave and swamped, injuring some of the

crew.

Only a

handful

of competitors in the board and ski events had negotiated

the break successfully,

and eventually there had been more swimmers in the board

race than there

had been in the surf race. Few of those who threaded their

way through

the waves on the way out managed to get back to the beach

still attached

to their boards.

In the R.

and

R. event the Hawaiian beltman had failed to reach the buoys.

In surfing

circles

this is the greatest disgrace of all.

Hawaii's

stakes

were low that day.

Now they

were

taking their little balsa surfboards out through the rip in

the centre

of the beach.

A balsa

surfboard!

Very little

lateral

strength!

The thin

fibre

glass covering kept water out of the porous wood, but added

very little

in the day (sic, way) of durability.

Ten feet

long,

or less - not 16 like our own "tooth- pick" boards.

Their twenty

pounds weight was too light for Australian conditions!

Or so we all

thought.

So on the

beach

were about 200 very sceptical, slightly tolerant

Sydney-siders.

Watching the

long, ...

Page 17

... steep

escarpments

of water roll past them were a handful of Hawaii's best

surfboard riders

- not men from placid Waikiki Beach - but from the beaches

of Sunset and

Makaha on the other side of the Island of Oahu.

Beaches

where

the long Pacific swell sometimes rose to an awesome

thirty-five feet before

crashing on to the submerged bombora reefs hundreds of yards

off- shore.

These men

were

used to cracking waves of immense size, cornering their

boards parallel

across the face of the wave and flying, at bullet-like

speed, out into

the calm water on either side.

They could

"zip"

and throw their boards about in a manner Australians,

handicapped by 16

ft. of heavy wood, thought impossible.

First man

on to

a wave was Mike Bright.

Paddling

lying

down, he pushed on to a fifteen foot wave off the baths at

the south end

of Avalon, straight in front of the rocks.

Bright spun

his

board into a corner and in a flash was travelling in a

"parallel zip" across

the face of the wave, heading for the smooth rip water 150

yards away.

The crest

was

curling over him as he shot into the rip and fiicked his

board over the

top of the wave and back out to sea.

Bright had

cornered

150 yards across the front of the wave in 6 or 7 seconds,

during which

time the wave had made very little progress in a shorewards

direction.

Australians on the beach were stunned again and again as the Hawaiians shattered the popular theory that short boards were not good on big waves, and when they finished an hour later not a person had left the beach.

POWER TO

POWER

CORNERING

After the

carnival

I spoke to Greg Knoll (sic, Noll) of the American

surf team, who

said that fifty miles per hour or over was usual in a

parallel corner on

a 15 ft.-plus wave with those boards.

This

involves

what is known as "power-to-power" cornering.

"Power-

to-power"

means the power of the forward motions of the wave, exerted

on the "sideways

falling" motion of the surfboard.

In a normal

comer

this gives the speed of the wave, plus 50 per cent, as the

actual speed

of the corner.

But both

these

factors may vary, particularly the latter - the 50 per cent

- which is

actually the "power-to-power" factor.

The speed of

the wave can vary only within certain limits, but the

"power- to-power"

factor can be constantly changing.

For

instance,

a big southerly sea has good cornering characteristics.

The waves

are

usually not very long but have high peaks, about 20 yards

wide, which break

first. Catching the waves at one of these peaks, the board

is hurled down-wards

as the peak jumps before breaking.

This

original

impetus can add much to the power-to-power ratio.

The Hawaiians demonstrated this at Avalon, where the 16 ft. surfboard lost its glamour position in the ,Australian surfing scene.

INTRODUCTION

OF

SURFBOARD RIDING IN AUSTRALIA

How did this

type of surfboard, which was fairly unsuitable for riding

waves, come to

be accepted by surf-loving Australians?

The trend

away

from good wave boards was started by the champion surfboard

racers of recent

years, who found that the longer, thinner boards were

faster.

Speed

compensated

for loss of manoeuvrability on a wave, and because these men

were all stars,

the general

run

of board riders followed the fashion they set.

However,

many

types of board had been seen on the Australian coast in the

30 odd years

before these came into vogue.

Surfboard

riding

was originally introduced into Australia by an Hawaiian,

Duke Kahanamoku.

Riding the

waves

in Hawaii goes back a long, long time, and many native

legends involve

cracking waves in j or on a various assortment of crafts

(sic, craft).

The Hawaiian

Commercial Advertiser ...

Page 18

... of

April 2,

1868, reports what it describes as "the greatest aquatic

feat in the world".

The hero of

the

story is a man called Huloua, who lived near Ninole, on a

big island of

Hawaii.

On this day

tidal

waves struck the island and Huloua and his wife fled to the

hills.

But Huloua

remembered

he had left his money behind, so he dashed back to his

house, which sat

in the path of the first of the giant waves.

The wave

struck

the house and the angry waters sucked it out to sea with

Huloua still inside.

Miles out to

sea, but undaunted, Huloua wrenched a rafter from the

ceiling (he was a

powerful man) and rode the next wave - a mighty 60-footer -

to the shore,

landing on a hillside where his wife awaited him.

The wave he

rode

is reported to have wiped out four villages and killed over

one hundred

people. With this story in mind, not many would dispute that

Huloua is

the grand daddy of all surf riders, and a good man on a big

wave to boot.

Duke

Kahanamoku,

who could be described as a more modern Huloua, was here in

the summer

of 1915, fresh from Olympic swimming triumphs.

When the

Duke

arrived Australians had mastered only the art of body

shooting.

Nothing

successful

had been done on a board, although a few attempts had been

made to master

the tricky sport.

Kahanamoku

carved

a huge lump of Australian sugarpine into the shape of a

surfboard, 9 feet

long, 25 inches wide and weighing 95 pounds.

When he had

finished

the board he promised the locals at Freshwater an exhibition

one Saturday.

On the day

the

Duke was accompanied by three Australian board riders, Geoff

Wylde, "Busty"

Walker and Claude West.

All four

left

the beach together, but the Duke had caught four waves

before any of the

Australians got out, and when they did, they saw Kahanamoku

standing backwards

and waving to them as he disappeared shorewards on a huge

wave.

|

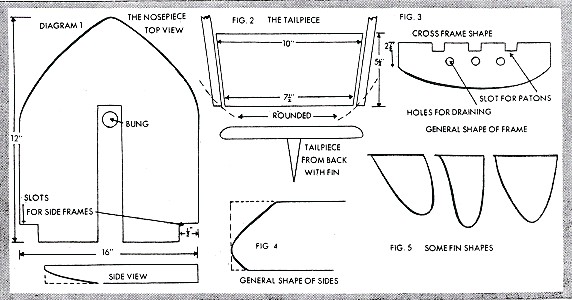

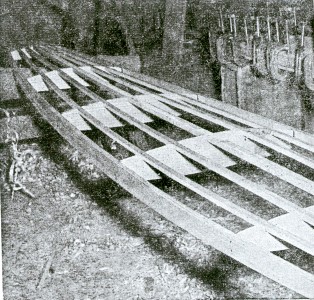

Note the cross frames supporting four horizontal stringers (sic, five longitudinal?). The cross frames are for general frame strength, while the stringers support the ply. |

Kahanamoku

impressed

that day with his skill and daring, a new aspect of surfing

was revealed.

The

possibility

of riding the waves on a piece of wood had seemed remote

before, but was

now very feasible.

The movement

towards surfboards in Australia had started.

When

Kahanamoku

left, West, Wylde and Walker started experimenting in shapes

of boards

and techniques of riding the waves.

They were

joined

by others and a number of solid boards were constructed.

These boards

varied from 6 ft. (minimum) to 9 ft. 6 ins. (maxi- ...

Page 19

... mum)

and weighed

upwards of 75 Ibs.

The board,

which

hardly floated at all, were pushed on to many a fine wave

and Australian

surfboard riders became known among the best in the world.

But these

solid

boards floated low in the water - in most cases completely

under the surface

- and it was a strong man who could push his board on to a

wave before

the wave broke.

It was

tremendously

hard to get them out through a big sea, but once on a wave,

they gave an

"armchair" ride.

But catching

the waves in dangerous spots such as bomboras, where one

mistake on the

part of the rider or an inadequacy in the design of the

board could mean

possible death, these boards were useless.

So just

before

the war, when Fitz Lough started building hollow boards,

things really

began moving. Lough was the pioneer of hollows and built a

board 11 to

12 feet long and curled up at the front like a snow ski.

Waves could

now

be caught much farther out then before and every aspect of

board riding

was made simpler.

Boards

floated

higher, became longer, and acquired more glide.

A new era

was

beginning.

Down south

at

Maroubra a strong board movement was growing led by Lew

Adler, and it was

from here that many champion board riders came.

Also

building

"hollows" was Fred Hoinville of Bondi, who organised the

since discontinued

Australian Surf Board Association.

Hoinville

built

a parallel-sided board - dreadful on any waves, big or

small.

It was about

this time, just before the war, that a noticeable evolution

away from good

wave boards began.

The

champion paddlers

in board races found that a deep-sided hollow board, which

was more buoyant,

could get out more easily.

Boards

became

longer but narrower - first 14 ft., then 15, then 16.

After the

war

a new crop of surf-minded Australians inherited the long

boards.

There were

still

brilliant riders.

Men like Bob

Evans of Queenscliff and Roger "Hellfire" Duck of Manly

cracked the awesome

North Steyne bombora (sic, more commonly known as the

Queescliff Bombora),

while "Bluey" Mays of Bondi threw his board about in

hurricane seas.

But the

sixteens

were still difficult boards to handle well, and the number

of very good

riders was limited.

With the

evolution

away from these long boards comes one big advantage -

manoeuvrability.

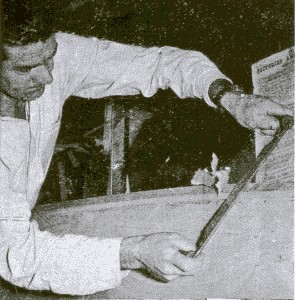

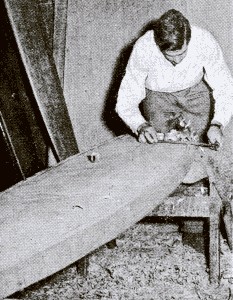

Gordon Woods using a spokeshave to round the sides. |

Rounding the sides of the board is a fairly important job, and takes some time. |

MAIN APPEAL

OF

THE SHORT BOARDS

The main

appeal

of the Hawaiian- type board, apart from manoeuvrability,

lies in the fact

that it has facilitated a previously difficult facet of the

sport - cornering.

Cornering

means

traversing across the face of the wave along the beach

instead of towards

it.

When the

wave

is about to break the board is straightened so that it can

be ridden through

the white water and up to the beach.

The

straightening

of the board can be extremely difficult for the sixteen

footer, and at

best, takes a matter of seconds.

An Okinuee

can

be flicked through a ninety degree turn and straightened

even while the

wave is curling over the board.

Alternatively

it

can be flicked up and over the wave and back out to sea

again before

the wave breaks.

STANDING

POSITION

ON BOTH BOARDS

On a sixteen

foot board the standing position varies from about 4 ft.

from the back

of the board on a small wave to a matter of inches from the

back of the

board on a large wave.

This means

that

the rider has between 12 and 15 feet of board in front of

him to control.

Particularly

in a large surf there is always the danger of the board

digging into the

front of the wave or becoming uncontrollable.

At increased

speeds in corners this foot- age builds up air-resistance

and fans up and

down in an alarming manner.

As a sixteen

footer has high flat sides which will not settle into the

wave it is comparatively

slow in corners.

Also, as

mentioned

before, difficult to straighten up when the critical

"breaking" time comes.

On an

Okinuee

the legs are placed farther apart and the normal standing

position is very

little distance behind the centre of the board.

In a

position

between three and four feet from the tail (which is only 6

feet from the

front) the board can be swiftly turned and easily controlled

in a parallel

corner.

The whole

side

of the board "grooves" into the wave and extra speed is

obtained by moving

towards the front.

On big waves

the front foot can be as close as two feet from the very

front of the board

- in complete ...

Page 20

...

contrast to

the 16 ft. board.

In the

coming

season Australians will be thrilled and amazed by the

spectacles created

by these new Okinuee boards.

A HOLLOW

HAWAIIAN

BOARD?

After the

Hawaiians

had impressed everybody with the shape and design of their

board a problem

presented itself to the board builders in Sydney - balsa.

The Hawaiian

boards were solid balsa - 10 feet long, 2 feet wide, and

from 4 to 6 inches

deep.

This much

balsa,

if it were available ; would have cost £60 in Australia.

With no

other

wood as suitable a number of experiments took place with

hollow boards.

The

intention

was to copy the shape and fiotation of the solid balsa

Hawaiian board.

Douglas

Jackson

and David Lyall of Bilgola Surf Club were the first to

launch a short

board.

Their boards

were about eight feet long, looked and fioated like a door,

but were good

performers on a wave.

They were

hard

to get out and the corners of their square front constantly

dug into the

water.

Sitting out

the

back waiting for waves was both an un-nerving and cold

pastime as the board

floated about six inches under the water.

But in a

corner

they were fast, though not as fast as a balsa board, and

they were manoeuvrable

enough to be very encouraging.

Then a

month after

the Hawaiian surf team had gone home well-known board rider,

Gordon Woods

of Bondi, turned out a beautifully moulded hollow board,

which at first

glance looked exactly the same as its balsa counterpart.

He had not

only

copied the shape, he had improved upon it in many respects.

Gordon had

bought

one of the three Hawaiian Balsa boards which were left here,

and studied

its shape carefully.

The board he

made was faster and had better flotation than the balsa one,

it would catch

a wave sooner and was not very much heavier.

Its

performance

on a wave was terrific, although the balsa board was a

little more comfortable.

Gordon had

proved

that an Australian-built 10 foot board, copying the Hawaiian

shape, was

comparable

with

the Hawaiian one.

So much so

that

he has already received two orders from Honolulu.

Ten feet was

found to be a good, all-purpose size, but a shorter board is

more manoeuvrable,

though slower to paddle.

And "slower

to

paddle" means that waves are harder to catch.

You'll have

to

decide for yourself what size suits you best.

Keep in mind

that only a few inches in length make a big difference.

| Then

a month

after the Hawaiian surf team had gone home well-

known board rider, Gordon

Woods of Bondi, turned out a beautifully moulded

hollow board, which at

first glance looked exactly the sarme as its balsa

counterpart.

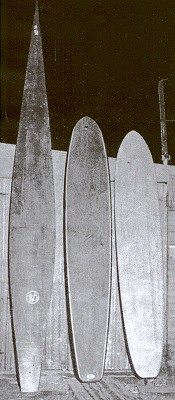

He had not only copied the shape, he had improved upon it in many respects. Gordon had bought one of the three Hawaiian Balsa boards which were left here, and studied its shape carefully. The board he made was faster and had better flotation than the balsa one, it would catch a wave sooner and was not very much heavier. Its performance on a wave was terrific, although the balsa board was a little more comfortable. Gordon had proved that an Australian-built 10 foot board, copying the Hawaiian shape, was comparable with the Hawaiian one. So much so that he has already received two orders from Honolulu. Ten feet was found to be a good, all-purpose size, but a shorter board is more manoeuvrable, though slower to paddle. And "slower to paddle" means that waves are harder to catch. You'll have to decide for yourself what size suits you best. Keep in mind that only a few inches in length make a big difference. The three different

types of board mentioned in the story.

|

|

THE NOSE

BLOCK

The

nose-block

is made of three inch deep maple (see diag. 1).

The slots on

the side are for the side frames, while the slot down the

centre is for

draining and placement of the bung.

The

nose-block

is simply cut to shape, as in top elevation diagram.

Shaping of

under-side

is not done until the board is practically finished.

THE TAIL

PIECE

The tail

piece

is also made of three inch maple (see diag. 2).

There are no

slots in this section as the side frames fit around it, not

into it.

THE SIDE

FRAMES

These are of

three inch by 1/2 inch maple and their length determines the

total length

of the board. Using a waterproof glue, they are first glued

...

Page 21

... and

nailed

into the slots on the nose piece.

Then they

are

glued and nailed around the sides of the tail piece.

All nails

used

in the construction of the board must be copper.

When the

glue

has set the back corners of the tail piece are rounded.

By virtue of

the shape of the nose and tail block the board will now have

fallen into

shape, close to what it will be when it is finished.

Final shape

is

now determined by the placing of the cross- frames.

Four

cross-frames

for a 10 foot board should be enough.

The board

should

be thickest about four feet from the nose so the longest

cross-frame is

put in here. Total thickness, including i inch shaped side

pieces, should

be about 23 inches to 24 inches at this point.

The

cross-frames

are equally spaced along the board.

They have

slots

cut in the top of strengthening stringers, and are bored for

the purpose

of

drainage

(see

diag. 3). Three or four stringers may be used, and it is

recommended

that

they run the

whole length

of the board; that is, from the nose piece to the tail

piece.

They need

not

be very thick - certainly no more than ~ inch.

See photos

for

positions of stringers and frames.

These show

four

stringers but three will be enough for an average-sized

person.

THE PLYWOOD

.

The frame is

now ready for the plywood - 1/4 inch three-ply.

The top of

the

board is planed and the plywood is glued and nailed.

Plywood must

always be nailed from the centre to the nose, both sides

together - then

from the centre to tail.

The top ply

is

put on first so that the frame will not warp when the curved

bottom is

placed.

A hole for

the

bung is now drilled through the top ply.

It may be

left

as it is or a metal bung may be mounted.

ATTACHING

THE

BOTTOM

Because the

base

will be curved a slight angle must be planed on to the side

frames to receive

it neatly.

This angle

can

be checked by the cross-frames, as it will correspond with

them.

Nail again

from

the centre.

Excess ply

must

now be planed off and the frame and ply is ready to receive

the shaped

edge strip. This strip is , inch by three inch maple, and

must be glued

on.

If a sash

clamp

is not available it can be lightly nailed, the nails being

removed after

the glue is dry. When the glue is dry this strip is

shaped-by spokeshave

or plane - so that it is curved (as in diag. 4) with a

fairly sharp edge

towards the bottom of the board.

The

underside

of the nose is now planed (as in fig. 1) so that the front

of the board

will cut through the water more neatly and not throw a

spray.

Now all

that remains

to be done is to fix the fin about two inches from the tail.

The fin

should

be about 8 inches high and can be mounted with fibre glass,

as firmly as

possible (see diag. 5 for shape).

General

sandpapering

and varnishing or painting should now finish the board.

At least

four

coats of varnish or two coats of paint are recommended.

The board is

then ready.

Now it's up

to

you but keep in mind that only constant practise will make

you a board

rider.

Handling the

shorter boards is quite similar to handling the conventional

style board,

although there are a few variations.

One thing

the

rider will notice as soon as he mounts the Okinuee is the

increase in manoeuvrability

and speed.

He'll have

to

make a whole revaluation of his board riding technique.

He must

remember

not to sit so far back on the board that the nose is

completely out of

the water. The correct position is at that point on the

board where the

rider's weight just lifts the nose from the water.

As a wave

builds

up behind, give three or four very hard paddles, then slide

to the back

of the board, to keep the nose from digging in at the bottom

of the wave.

The best

place

for beginners to learn is in rips where waves sometimes do

not break.

They must

remember

never to learn in the vicinity of a sandbank for it is on

these sandbanks

that waves dump.

When you

decide

the time has come to stand up on the board, do so as quickly

as possible.

Don't try

and

balance on the way up.

Get to your

feet

and then worry about balance.

If you

happen

to falloff, make sure you go to the side of the board not to

the front.

And don't

forget

that oniy practice makes good riders.

| He'll have to

make a whole revaluation of his board riding

technique.

He must remember not to sit so far back on the board that the nose is completely out of the water. The correct position is at that point on the board where the rider's weight just lifts the nose from the water. As

a wave builds

up behind, give three or four very hard paddles,

then slide to the back

of the board, to keep the nose from digging in at

the bottom of the wave.

Without the fin,

the board will skid and skitter about in the

water.

|

|

|

Australian Outdoors November, 1957, pages 16 to 21 . |

|

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |