surfresearch.com.au

|

surfresearch.com.au

paul gartner

: surfboard riding hints, 1937

|

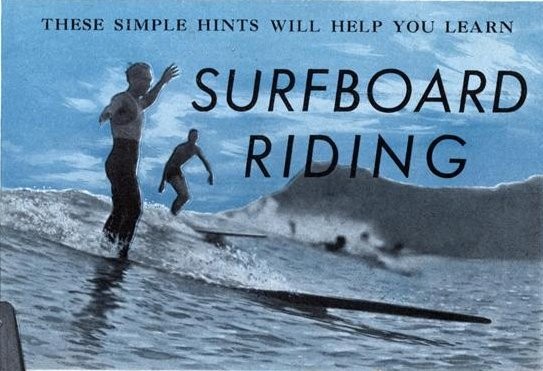

Paul

W.

Gartner : These simple hints will help you learn Surfboard

Riding, 1937.

Gartner, Paul W.:

: These simple hints will help

you learn Surfboard Riding

Popular Science

Volume 131 Number 1, July 1937

Modern Mechanix Blog

http://blog.modernmechanix.com/issue/?pubname=PopularScience&pubdate=7-1937

Introduction

Page 24

|

WHERE the sea

throws itself shoreward in smooth, powerful swells,

you will find the wave riders— bronzed, muscular

swimmers who have studied well the whims of Father

Neptune and know how to hitch their buoyant surfboards

to the bounding water.

Their shouts ring out

above the thunder of breakers, as they stand upright

on the polished planes of wood and rocket along on the

forward slope of a swiftly advancing wave.

Merely to witness a

masterful performance of wave riding imparts some of

the delicious thrill known to these aquatic

artists.

And, if you are at all

addicted to water sports, you will feel a commanding

urge to duplicate their feats.

Before you do, however,

it will be well to learn from the beginning some of

the fine points in the ancient art of hitching a

ride on the waves.

Most surfboards range

from ten to twenty-one feet in length, by eighteen

to twenty-four inches in width, and weigh anywhere

between thirty and 165 pounds, depending upon the

material and type of construction.

For wave riding,

preference is given the shorter board, generally

under thirteen or fourteen feet, since it is more

easily handled.

Boards of greater length

are usually to be associated only with veteran

riders, who are likely to own a number of surfboards

of varied design.

The longest boards,

twenty or more feet in length and only eighteen

inches in width, are used more for paddling races

than for actual surf riding.

|

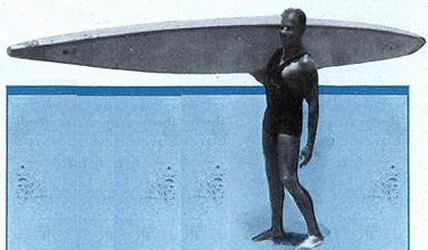

[Above:] Cigar shaped boards of

the air-chambered design.

The longer board is used

principally for paddling races.

Choose your

board according to your size and weight.

A youngster

may find an eight-foot board quite adequate, while a tall,

200-pound man may have his best success with an

air-chambered board not shorter than twelve feet.

The average

person will not be making a mistake if he practices with a

surfboard somewhere between ten and twelve feet long,

approximately twenty-two inches wide, and weighing not more

than fifty pounds.

In this

classification you have a choice between the traditional

ten-foot board, usually built of light balsa wood, and the

|

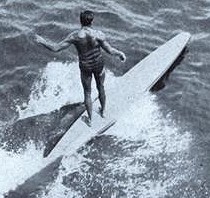

Most paddlers stroke

simultaneously. as shown below.

In

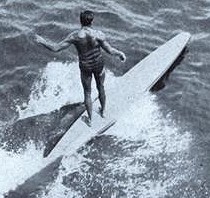

the photograph at the left, note the sideways

standing position,

which

permits the weight to be shifted easily to the

front or back of the surfboard.

|

| Page

25 [By Paul W. Gartner}

more

modern cigar-shaped board, which contains an air

chamber throughout its entire length.

Once

you have selected a good surfboard, it is advisable

that you first become a competent paddler.

Prone

upon your stomach, balance your weight on the board

so that the deck is almost level with the

water.

A

choppy surface will require a slight uptilt to the

bow.

Now,

arch your back and raise your shoulders with face

forward, and start to stroke with extended arms, as

though they were the oars of a boat.

Most

paddlers, especially beginners, prefer to stroke

simultaneously with both arms, although an

alternating, over-arm stroke, similar to that used

in swimming the crawl, also can be employed.

It

is interesting diversion, too, to paddle

Indian-style on the knees, or in a sitting position.

|

In tandem riding, the "passenger"

rides

In tandem riding, the "passenger"

rides

in

front of the steersman.

|

But whatever

the method, the stroke is made with the wrist and arm tensed,

and fingers cupped together.

Relax as the

arm is being carried forward.

On the hollow

racing boards, practiced paddlers can sprint at approximately

twice the speed of champion swimmers.

Distance also

is possible on the paddle board.

Beach guards

of Santa Monica, Calif., recently paddled from the mainland to

Santa Catalina Island, a distance of more than twenty-six

miles, in less than six hours.

The paddle

board also suggests adventure on lakes and broad rivers.

When resting,

merely sit upright on the board, astraddle near the point of

balance.

When

paddling, you have two methods of guiding your thin craft.

To negotiate

a slight curve, it is necessary only to vary the power of

your strokes, or to dip one hand shallowly as you increase

the force of the other.

But in order

to turn sharply, it may be advisable to drag one foot as

well.

To rest, sit straddle

of the bouyant

board.

|

Most buoyant boards will carry two

persons on a favorable surface, and you and a

companion may paddle tandem fashion, timing your

strokes rhythmically like members of a rowing

crew.

The

more experienced person should ride behind and

act. as steersman.

The

paddle board can be used to advantage in

accomplishing a water rescue, particularly where

a swimmer has become tired and is unable to

return to shore without assistance.

Should

the subject be helpless, it is recommended that

you sit astraddle the board when attempting to

drag his weight into an advantageous position.

The

beginner should exercise caution when taking a

surfboard through the breakers.

Always

keep the bow headed squarely into the incoming

waves, and time your progress so that the

curling water will not crash down upon

you.

You

may buck through breakers that are largely

spent, but watch out for those which still have

a forceful rumble.

Where

waves are breaking is the real danger

zone.

|

When

attempting to pass a breaker at “this point, it generally is

advisable to slip from your board and, holding it firmly by

the stern, drive it deeply into the rolling water, ducking as

the crest of the wave sweeps over you.

Should you

happen to lose hold of your craft, remain submerged until the

breaker has passed, and even then come up with your arms above

your head.

Strong men

have been knocked unconscious when struck by a runaway

surfboard.

Now that you

have become familiar with the buoyant surfboard, you must

learn to judge waves.

Except when

swells are uncommonly high and steep, the best point to catch

a wave is just outside the area where local breaks begin.

Where there

are shoals you will find the first crests of white water.

Heavy ground

swells generally run in series, and most riders prefer to let

the first one or two go by, since the later waves usually are

smoother and better for riding.

It is the

habit of these largest waves first to break locally, and the

white crests will gain breadth in accordance with the

shallowing water.

It is on this

smooth “shoulder” beside the foam that surfboards slide to the

greatest advantage.

In hitching to

a wave, it is important that you keep your board at right

angles to the advancing slope of water.

Keep well back

on your water sled, so that the bow will ride fairly high,

particularly if the wave is steep.

Try to paddle

at approximately

Continued page 111.

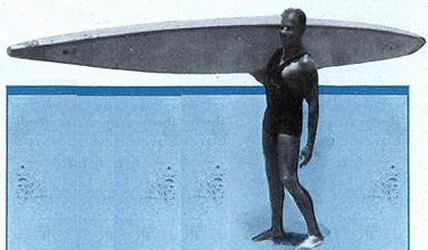

The light hollow surfboard is

easily carried on the shoulder.

The light hollow surfboard is

easily carried on the shoulder.

At

the left, four riders have caught a wave and are

are seen in the art of rising to their feet.

|

|

Page 111

Continued

from page 25.

|

In rescuing a swimmer , it is

best

to straddle the board

while

dragging his weight.

|

the speed of the

swell.

As the stern lifts, throw your weight slightly

forward in order to gain a final impetus for the

slide.

If all is well, you now will start to glide down the

slope of water, just as a toboggan speeds down an

icy hillside.

Once under way at a

pace that drives wind and spray whistling by your

ears, your first maneuver is to “slide,” or angle to

one side, away from the break of the wave.

This may be accomplished simply by shifting your

weight and, if the board fails to respond instantly,

using a foot as a rudder.

Failure to come into a slide sometimes causes a

board to dive, especially on steep waves.

On this initial ride you probably will be content to

maintain a prone position, but continued practice

will eventually find you standing on the speeding

plane.

Many riders come to

their feet in a single movement, holding the board

steady with their hands.

The beginner, however, probably will feel more

secure if he first draws his knees beneath him.

An erect wave rider generally has one foot slightly

in advance of the other, in some cases standing

almost sidewise to the direction of travel.

Like a tight-wire artist, you may have to use your

arms vigorously in balancing.

|

GUIDE your

sensitive craft by shifting your weight from side to side.

If the bow

appears to be dropping, take a short step backward to alter

your balance slightly. Conversely, a

step or jump forward will tend to lower the bow and send you

farther down the slope of the wave.

A zigzag course can be maintained by careful steering.

Expert wave riders have been known to dart in and out among

the mussel-crusted pilings of a pier while standing erect

and steering solely by balance.

At length, you

approach shallowing water and the point where all waves must

break.

To prevent any

mishap in the breakers you will “cut out.”

Step well back

on your board and, as the bow lifts, lean sharply to one side.

This will

allow the wave to pass on beneath you.

Once you have

escaped a wave, however, be quick to paddle seaward again,

lest you be mauled by the following breaker.

Sometimes a rider is able to survive the break and continue

his ride clear to the glistening sand, but no matter how

experienced he may be, there always is considerable danger

when passing the break.

Short rides

can be had on waves that already have broken. In fact, this

elementary form of surf riding has a considerable following,

especially among younger swimmers and persons with small,

improvised boards.

In catching a

half-spent breaker, keep well back on your board and paddle

strongly as the water rolls against you.

Sometimes you

may be carried to the beach.

On

the greater swells before the break, tandem riding is

gaining popularity.

The

additional weight makes a wave more difficult to

catch, and a steeper slope is preferable.

The

steersman, who rides behind, first rises to his feet,

and then assists his companion to an upright position

very close to him.

A

sturdy rider sometimes is able to hold a passenger on

his shoulders.

Those

who have years of wave-riding behind them are able

to perform sensational feats on the speeding

surfboard.

It

is not unusual to see a man balancing on his head

and hands while the craft is in full swing.

Others

are able to ride backward, turning around by a

single quick movement.

Two

persons riding parallel may change boards in

midflight.

Such

trick riding requires a smooth, clean wave.

Another

stunt that catches the eye of the visitor is

free-board aquaplaning.

As

practiced on the hollow board, the rope attached to

the power boat is held in the hands of the rider,

who maintains his position on the board solely by

the friction of his feet on the smooth

surface.

Sharp

turns with the free board are deadly, but in case of

a spill you still will have your craft near at hand

for support, even though the boat speeds on.

|

Here

the swimmer

is

paddled ashore.

|

IN “BODY

SURFING”—riding waves without a board—the technique varies

from that practiced on the surfboards.

Although

very steep swells may be taken in this manner, most body

surfers elect to catch a wave just as it is breaking and

then travel with their heads and shoulders just ahead of the

“suds.”

Where the

breakers are not strong, you may find it a help to kick the

feet while under way, or to bend one or both legs at the

knees.

Some “body

surfers” prefer to extend their arms forward, but you will

note that under most circumstances the most proficient

performers will keep their arms close to their sides.

This

position allows the chest, which is the body’s region of

greatest buoyancy, to be as far as possible in advance of

the rolling water.

And now, as

we rest upon our surfboards, awaiting a green swell which

moves silently toward us, let us hail the cradle of the wave

rider — Hawaii.

May we

salute, also, that ancient island conquerer, King Kamehameha

I.

Legend tells

us that, even when old in years, he was a skillful wave

rider.

But surely

no man is old who can hitch his surfboard to the untamed

waves.

To him, and

to those other sunny-souled people of the islands, let us be

grateful for at least one secret of prolonging youth.

surfresearch.com.au

Geoff Cater

(2000-2013) : Paul Gartner : Surfboard Riding Hints, 1937.

http://www.surfresearch.com.au/1937_Gartner_PopSc_July.html