|

surfresearch.com.au

e.k.

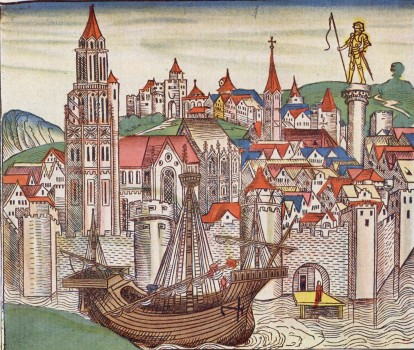

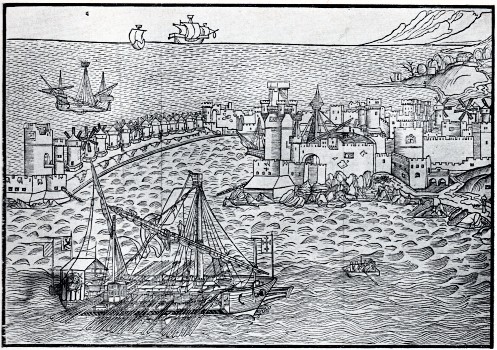

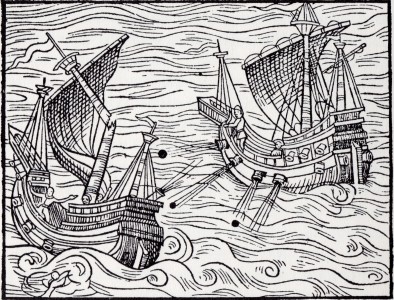

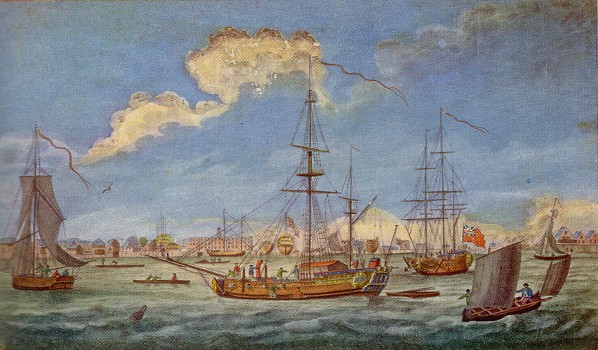

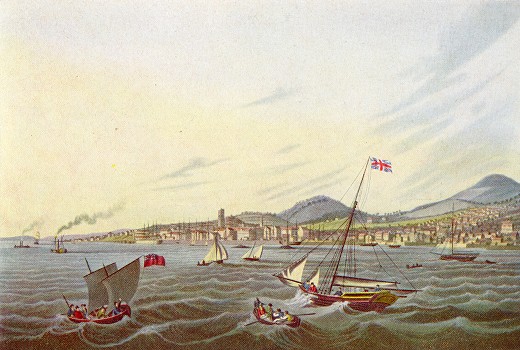

chatterton : old ship prints, 1927

|

E. Kebel Chatterton : Old Ship Prints, 1927.

Extracts from

E. Kebel Chatterton: Old Ship Prints,

John Lane The Bodley Head Limited, London, 1927.

Spring Books, Dury House, London, 1965.

Introduction.

Edward Keble Chatterton (10 September 1878 – 31 December 1944) was a prolific writer who published around a hundred books, pamphlets and magazine series, mainly on maritime and naval themes.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Keble_Chatterton

The illustrations are only attributed in the preface as "courteously reproduced" from the collections of several companies and individual collectors.

Edward Keble Chatterton (10 September 1878 – 31 December 1944) was a prolific writer who published around a hundred books, pamphlets and magazine series, mainly on maritime and naval themes.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Keble_Chatterton

The illustrations are only attributed in the preface as "courteously reproduced" from the collections of several companies and individual collectors.