Riding

the Surfboard

By DUKE PAOA

(Duke Paoa was born on

the island of Oahu, within sound of the surf, and has spent half

of his waking hours from early childhood

battling the waves tor sport.

He is now 21 years of age, and is the

recognized native Hawaiian champion surf rider.

Duke and the members of the Hui Nalu,

an organization of professional surfers at Waikiki,

have supplied the material for this

article on the national sport of Hawaii.)

These photographs

of Surfriding are from the negatives of Alfred R.

Gurrey, Jr.,

and some of the results of

three years work in surf

photography.

It necessitated going right out

against the incoming surf, right at its height,

and meant invariably a swamping of

the canoe and soaking for all in it.

Mr. Gurrey felt amply repaid for his

day's outing if at the end of the day he

returned with his camera and one

unspoiled negative out of twelve.

Would you like to stand like a god before the crest of a

monster billow, always rushing to the bottom of a hill and

never reaching its base, and to come rushing In for half a

mile at express speed, in graceful attitude, of course,

until you reach the beach and step easily from the wave to

the strand?

Find the locality, as we Hawaiians did, where the rollers

are long in forming, slow to break, and then run for a great

distance over a flat, level bottom, and the rest is

possible.

Perhaps the ideal surfing stretch in all the world is at

Waikiki beach, near Honolulu, Hawaii.

Here centuries ago was born the sport of running foot races

upon the crests of the billows, and here bronze skinned men

and

women vie today with the white man for honors in aquatic

sports.

There are great, long, regular, sweeping billows, after a

storm at Waikiki, that have carried me from more than a mile

out at sea right up to the beach; there are rollers after a

big kona storm that sweep across Hilo Bay, on the Big Island

of Hawaii, and carry native surfboard riders five miles at a run, and on the

Island of Niihau there are even more wonderful surfboard

feats performed.

A surfboard is easy to make.

Mine is about the size and shape of the ordinary kitchen

ironing board.

In the old days the natives were wont to use cocoanut logs

in the big surf off Diamond Head, and sometimes six of them

would come in standing on one log, for, of course, the

bigger and bulkier the surfboard the farther it will go on

the dying rollers; but

it is harder to start the big board, and, of course, on the

big logs one man, the rear one, always had to keep lying

down to steer the log straight with his legs.

At Waikiki beach, Queen Emma, as a child, had a summer home,

and always went out surfing with a retainer, who stood on

the board with her.

Today it is seldom that more than one person comes in before

the wave on a single board, although during the past year

some seemingly wonderful feats have been attempted.

I have tried riding in standing on a seven-foot board with a

boy seated on my shoulders, and now I find it not impossible

to have one of my grown companions leap from his board,

while it is going full speed, to mine, and then clamber up

and twine his legs about my neck.

Lately I have found a small boy, part Hawaiian, who will

come in with me on my board, and when I stand, he stands on

my shoulders, and even turns round.

To quote from Alexander Hume Ford, editor of the Mid-Pacific

Magazine, who organized the Surf riders Club at Waikiki:

Surfboard riding is an art easy of accomplishment to the few

and difficult to the many.

It is at its best when the rollers are long in forming, slow

to break, and, after they do, run for a great distance over

a flat, level bottom, such as the coral beds at Waikiki,

which is perhaps the all-year-round ideal surfboarding bit

of water in the whole world. There are three surfs at

Waikiki: the "big surf" toward Diamond Head, in front of Queen

Liliuokalani's summer residence, where the most expert surfboard riders and the native boys disport

themselves; the "canoe" surf, nearly in front of the Moana Hotel, where the

majority of those who stand on the board dispute rights with

the outrigger canoes that come sliding in from a mile out at

sea before the monster rollers; and the beginners, or

cornucopia surf- a series of gentle rollers before the

Outrigger Canoe

Club's grounds and the Seaside Hotel.

Here, as a rule, beginners learn the art of balancing on the

board.

The water for several hundred yards out is but waist deep,

so that the mallhini [sic] (new-comer) can stand beside his board, wait

for a wave, give his board a forward push, jump on, and race

in toward the beach before the foaming crest.

He quickly learns, lying down, to guide the board by moving

his legs, like a rudder, from one side to the other.

There is nothing difficult in mastering this portion of the

art or surfing, but out in the deepwater it is quite another

proposition. There you have no foothold from which to gain a

start, which must now be given the board by the power of the

hands.

It is half a mile out to

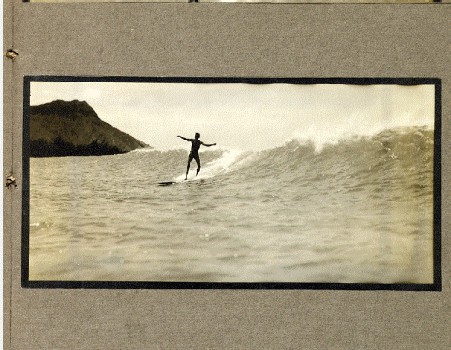

Page 14

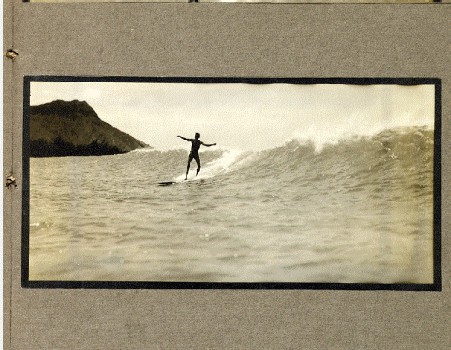

ON THE CREST.

Copyrighted by A. R. Gurrey, Jr |

|

the big waves, or "nalu nui," and a long

"hoe,' as the overhand windmill stroke that takes you out is

termed.

The intending surfer launches his board by grasping it in

both hands by the edges, so that it balances, rushes down

the slightly sloping beach, and throws himself upon the

board as he casts it upon the waters with a forward movement

that gives it a good start and sends it beyond the first row

of little breakers.

Then begins that constant, steady, windmill movement of the

arms, the hands acting as paddles, and the six or seven-foot

plank

of light wood swiftly glides out to sea.

To the beginner the exercise soon tires to exhaustion; the

neck and back ache, and the points of the ribs that touch

the board seem to cut through the flesh.

Perseverence, however, overcomes all obstacles, and after a

few days new muscle is developed and the stiffness is

forgotten.

Out in the deep surf, the board goes outward under the

waves, a diving tip being given the board just as it bucks

each on rushing breaker.

Once out where the waves foam, the surfer sits on his board,

which, of course, sinks until only an inch or so of the tip

is above water, and waits for the wave.

Several may pass, then afar off he notices the one he wants.

It is coming onward, a great, green roller with a ridge of

almost imperceptible spray along its entire length.

This is the wave that will curl and break to perfection,

then rush on for hundreds of yards - a Niagara of foam.

The line of surfers prepares, and as the base of the

mountain of water reaches them, there is vigorous and deft

paddling with all the strength that skill can put into

trained arms, and the great effort is made.

Some rise rapidly to the crest of the billow and sink behind

it; they have lost the wave.

Others keep down in the hollow just before the wall of

green.

It breaks, and these fortunates are lost in the foam, rise

through it, standing on their board, are lifted to the top

of the white crest, and by skillful balancing, and guiding

their boards with their feet, send them down in the bias

until once more they are in front of the on-rushing mass of

water.

Some of the boards, of course, are divorced from their

owners and go sailing in the air, while the surfer dives

involuntarily toward coral.

Few, however, are the accidents of surfing, and it is

doubtful if anyone has ever been seriously injured at this

sport which has come down to the "haole" from the old kings

of Hawaii.

For several years past the sport of surfing had been on the

decline, for as the vacant lots facing the beach at Waikiki

were taken up by private ownership, the small boy of

Honolulu was forced to give up his favorite sport.

It was on account of this injustice to the small

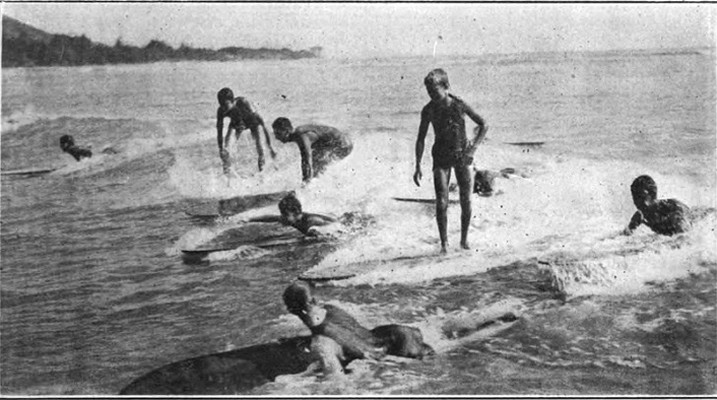

Page 15

Copyrighted by

A. R. Gurrey, Jr.

THE MALHINI SURF.

|

|

boy that the Outrigger Club was formed in

April, 1908.

The club soon numbered several hundred members.

New members were taught to ride stand-upon the surfboard,

and so popular became the revival of the old Hawaiian sport

that even the ladies began to take a deep interest in it.

A number of young girls have learned to stand upon their

boards, riding the waves, and together with their mothers

and older sisters have organized an auxiliary club.

Neither surfboarding nor driving the big native canoes

safely before the roughest waves are accomplishments beyond

the acquirement of the "haole" or white man.

There are white boys fully as expert as any Hawaiian youth,

both in the canoe and on the surfboard.

A white lad was the first to win a cup at a carnival of

surfriders.

Mark Twain tried to master the art of riding the surfboard,

many, many years ago.

He describes in vivid pen pictures the Hawaiian boys and

girls who danced upon the tips of the biggest breakers, and

how his board started by a big kanaka, caught a wave and

shot with express speed toward the beach, while he shot with

equal rapidity down toward the coral bed beneath the waters

of Waikiki bay.

It is difficult to learn to ride the surfboard without an

instructor, but a few simple hints will enable anyone to

master the art.

I quote from one who learned and wrote of his experiences:

The small boys of Waikiki took me in hand when I was ready

to take my first lesson on the surfboard.

It is their delight to initiate the malihini (stranger).

Few of them get beyond the initiatory exercises.

I was given a board, a bit or redwood, pointed at one end,

not six feet long, about sixteen inches wide and perhaps an

inch and a half thick.

"Just follow us,'' called one of the three eager tutors

selected from the delighted group of would-be instructors.

Soon we were out in deep water.

Nearly a mile out at sea the big, long billows, for which we

were headed, began their thrilling run, to break and reform

thrice before reaching the beach.

The first bit of advice from my tiny tutors was: "If a

breaker does strike us, just duck the bow of your board and

it will go through."

Each of the youngsters was now lying flat on his board, the

tips of his feet just lapping over the end, and the small

arms revolving

like windmills as the three boards flew through the water,

while mine lumbered on far behind.

"Come on!" they called in chorus, and I tried to obey.

The windmill motion consists of keeping the arms going

around like the sails of a windmill on either side of the

board, and strange to say, once the muscles of the arms and

shoulders are accustomed to this motion, it tires less than

any regular form of swimming.

The first of my troubles was that my chest where it rested

on the board began to chafe and ache; this the small boys

pleaded with me not to mind, as In a day or so I would not

notice it at all; this I later found to be true,

Page 16

SHOREWARD

BOUND.

Copyrighted by A. R. Gurrey,

Jr.

|

|

but that first afternoon it did not seem

possible that my ribs would not in time wear through the

skin.

However, I struggled on, and we approached the great

rollers.

The first wave we permitted to pass under us; than there was

a cry of "nalunui" (big wave coming); then "Hoe!—Hoe!" I

felt my-

self lifted on the advancing slope of the on-coming billow,

three pairs of active young muscles gave my board a great

start forward, onward and downward as though shot from a

cannon.

I was well forward on my board - in accord with instructions

carefully instilled, my feet flew up into the air - I clung

to the bow of my plank and with it did a series of

cart-wheels to the accompaniment of a chorus of cheers and

shouts of laughter; the small

boys had also plunged forward, using their bodies as

animated surfboards, and were riding my wave au-naturel.

As it finally passed me by and I came up its rear I could

see their smiling, happy faces on its crest turned toward

me.

There was a chorus of "You were too It did, but the board

was left behind.

Other youngsters, of all shades and complexions, and far

forward on your board," an exchange of gleeful chuckles, and

the three youngsters descended on my side of the wave to

give me the second degree.

"Always let your board go when she starts to dive," one of

them urged, "because sometimes if the surf is very high she

goes down 'til she strikes coral at the bottom."

Another of these cheerful, charming youngsters now thought

it time to ask if I could swim.

It seems there are persons foolish enough to come out half a

mile from shore on a surfboard who cannot swim a stroke.

I assured my initiators that I could swim, and, their

conscience at absolute peace, they prepared to proceed with

the grilling.

I was told to hold the board amidship and half kneel; it was

explained that in this posture the wave

The advancing water caught it and I lunged would strike and

carry me on at great speed, gleaming hides, that shone

dripping and resplendent in the sun, had now gathered to

witness the sport, and everyone was invited to participate

in the giving of the great third degree.

I have a vivid recollection of strange shouts, my board

almost jerked from under me, shot forward, and I, surrounded

by the white, foaming water, began sinking downward as on a

toboggon slide, yet onward with the speed of a cannon ball -

the spray almost blinding and strangling me; then as I sank,

clinging to my board, halfway down the slide of the wave, I

could begin to take notice.

On either side of me were my angelic tormentors, standing

erect on their boards, shouting encouragement and urging me

on - as though I could stop in that mad rush of waters, even

if I wished to.

From the crest of the wave a brown skinned native Hawaiian

dived from his board and arose beside me to shout confusing

orders in my face - from the other side another youngster

dived from his board and arose to grasp mine.

It tilted, and there was a shout of glee; it took the great

green wall of water on the bias, skimmed along at

accelerated speed - diagonally - and I could see the havoc

that was coming; boards dove under me - boys over me, and

one landed on the small of my back; there was a general

confusion and mix up in the seething waters, and I emerged

from the third degree coughing and spluttering to be taken

In hand for my diploma and final 33rd degree.

I was to stand on my board.

The wave came, the start was made, and my bit of wood was

fairly caught In the rush of waters.

Steady and even she rode the wave, then the cry came to

"stand!"

I tried it.

There was a rapid divorce from my board; we met later, and I

was pulled away from the wreck.

Unanimously it was agreed that I had earned my diploma, and

was worthy to learn the art of riding a surfboard.

"But I can ride," I expostulated.

There was a roar of hilarious, derisive laughter, and one of

the youngsters cried:

"Come on, then - let her go!"

Instantly all hands began to paddle - the windmills were in

full swing and the boards shot through the waters (all but

mine), caught the advancing slope, slid downward, and were

carried in in the rush.

I sank back behind the wave with my board as though I had

never made an effort to go forward.

Again and again the attempt was made, and again and again

failure was the result.

It was easy enough to understand just how the thing was done

by watching others go through the operation - but that was

no practical help.

The boys were

Page 17

"CARE FREE.'

Copyrighted by A. R. Gurrey, Jr. |

|

right when they advised, "It takes experience; just keep at

it; some day you'll learn the trick, and then you'll wonder

how it was you didn't get it the first day."

I learned in half an hour the secret I had sought for weeks.

A young hapahaole (half- white, half-native) took pity on

me.

He was the champion surfer of the Island - who, on a brief

visit to America once astonished the natives of Atlantic

City and was arrested by the police for riding in on an

ironing board upon the top of a great roller, to the seeming

peril of the hundreds of conventional bathers in the surf -

the first time in America, doubtless, that the little board

was used in our breakers - and half an hour after this hero

took me in hand I was riding the surf to my heart's content.

The first bit of instruction from my new tutor was to

balance myself; he showed me how in shallow water he could

stand until the

wave was almost upon him, and then spring sideways upon the

board, balancing so that resting on the tips of two ribs he

could wheel about as on a pivot - then he showed me how, in

deep water, to mount my plank with a side-ways motion.

My premier lesson was in the shallows.

"First," said my instructor, "I want you to learn how to go

before a wave; get on your board, now put your arms out

straight, perfectly rigid—go."

The wave came, there was a gentle shove from behind, I

kicked my feet up and down as instructed, and shot forward -

it was a complete success.

The next time I bent my elbows and slipped back through the

wave.

"That acts as a brake," said my instructor; "as long as you

keep your arms rigid you can go before the smallest wave,

but the moment you bend them, back you slide.

If you want to get up on your board, jerk yourself up

quickly without bending your elbows.

And so, with sensible hints here and there, my instructor

quickly initiated me into the mysteries of the board; its

secrets became mine.

When I would get a fair start and bring up broadside to the

wave, my tutor was there to stop me.

Soon I learned, by balancing myself amidships and waving my

legs, from the hips down, either one side or the other, to

perfectly guide my board before any kind of breaker.

In a little while this method seemed to be acquired most

naturally.

I was ready now to practice by myself, first in the

shallows, springing on my board with a forward shove just

before the wave broke, and catching its momentum - and in

deep water by remaining on my board and watching for the

proper wave.

But there again I had to be taught how to judge the waves

and which to trust myself upon - in fact, with the

instruction of a

man who knows how to teach, anyone may acquire the art of

surfboarding to perfection.

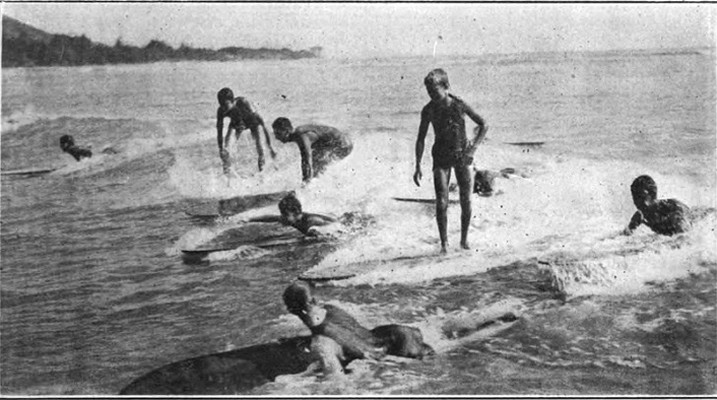

Our Navy, the Standard Publication of the U.S.

Navy

Volume 7 Number 10, February 1913

Page 45

"CIRCUS STUNTS"

Copyrighted by A. R. Gurrey,

Jr.

Not the exact image, but

similar.

|

|

A familiar sight at the famous bathing

beach at Waikiki, Honolulu, Hawaii.

The Hawaiian youth, trained to the water from infancy is

perhaps the most expert swimmer in the world.

The "stunts" executed on their surf-boards may be favorably

compared in points of skill and daring with the ski-runners

of the Scandinavian peninsula.

Much practice is required to enable one to navigate a

surf-board and the efforts of men-o'-warsmen to master the

art is a source

of much merriment to the natives.

That this sport is not indulged in on the Atlantic coast at

the popular beaches is due to the fact that a certain form

of wave is

necessary in order to cause the board to ride on its crest.

Our Navy, the Standard Publication of the U.S.

Navy

Volume 7, Number 11, March 1913

Page 37

KILLS EEL WITH

BARE HANDS.

"Duke" Kahanamoku, the world's champion swimmer, killed a

gigantic eel that attacked and drew him ten feet under the

water, with his bare hands on January 27, at Waikiki,

Honolulu, Hawaii.

The young Hawaiian lost the index finger of his right hand

in his battle with the monster which lasted for over two

minutes under

water.

He was unconscious when rescued by companions and the body

of the eel, the largest ever seen in Hawaiian waters, was

floating

near.

It had been choked by the intrepid swimmer.

Mr. Kahanamoku was winner of the chief aquatic honors at the

Olympian games in Sweden last year, and his article in OUR

NAVY

a few months ago on surf-riding, at which sport he is a

champion, drew much favorable comment from our readers.