Page

248

They have a variety of methods of

catching fish.

At King George's Sound

I have seen them take a quantity of whiting in the following

manner :

Two or three women

watch the shoal from the beach, keeping opposite to it,

while twenty or thirty men and women take boughs and form a

semicircle out in the shallow bay as far as they can go

without swimming, and then, closing gradually in, they hedge

the fish up in a small space close to the shore, while a few others go in and throw

them out with their hands.

By this primitive

method, skillfully executed, I have seen a large quantity of

fish caught.

At Swan River, I have

watched them drive a shoal of large schnappers into water *

*See Fig. 253, from a

native drawing. Native of King George's Sound.

Page 249

too shallow for them

to swim in and spear and catch a great number of fish weighing from ten to fifteen pounds

each.

On the Murray River they use

boats made of a single sheet of bark, and on the north-west

coast of Western Australia they make rough log canoes for

fishing.

In South Australia I

have seen them take out to sea a beautifully- made net, five

or six feet wide and fifty or sixty feet long, weighted at

one edge so that, while treading the water and holding it

out at full length, parallel with the shore, it is in a

vertical position six feet deep.

Others men and women

would then swim out for a quarter of a mile or more, and,

closing in, drive the fish against the net and then spear

them.

The Murray River

natives use spears for fishing made of the reed which grows

in vast beds from Swan Hill downwards for thirty miles, and

also at Lake Moira above the confluence of the Goulburn River.

These spears are

pointed with bones of the emu, or such substitute as they

may be able to procure.

They also use heavy

jagged spears made of miall (sic) or other very hard wood for

fishing.

Much ingenuity is displayed

in the manufacture of nets by the Coast tribes and the

natives of the Murray River, from string which, where

bulrushes grow, is made from the fibrous root of that plant, called on the Murray Balyan.

They peel off the

outer rind of the root, and lay it for a short time in the

ashes ; they then twist and loosen the fibre, and by chewing

obtain a quantity of gluten, somewhat resembling wheaten

flour, which affords a ready and wholesome food at all timed

to the tribes which inhabit the vast morasses in which the reeds and bulrushes abound.

They chew the root

until nothing is left but a small ball of fibre, which

somewhat resembles hemp.

These balls are then

drawn out, and rubbed with the palm of the hand on the bare

thigh of the operator, while a small wooden spindle twirled

with the fingers of the other hand twists and receives the

string.

Among the few

specimens of art manufactured by these primitive people none

are more like our own than the nets of South Australia and

Victoria.

Fishing with nets

seems to have been a very ancient practice in different

nations.

Suetonius states that

Nero was accustomed to fish with a net of gold and purple.

Plutarch mentions

corks and leaden weights as an addition which nets had

received.

Homer supposes that

nets were not used by the ancient Egyptians.

The Egyptians did,

however, use weirs and toils in their fisheries.

The use of fish-spears

appears very clearly in the paintings of ancient Egypt.

Page 257

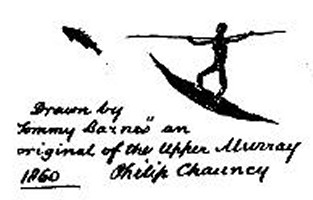

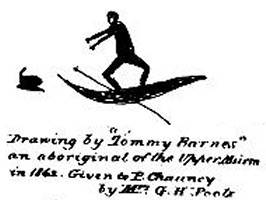

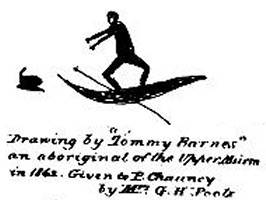

The annexed plates (Figs. 253

and 254) are from drawings with pen and ink by an

untaught Aboriginal lad of the Upper Murray, known as

"Tommy Barnes."

No. 1 gives a

good idea of a war-dance at the top and a corobboree

beneath, in which the dancers wear girdles round their

bodies, and fillets of emu feathers or of small boughs

round their legs, and hold waddies in their hands, which

they energetically strike together, keeping time with

the dance.

The women,

fourteen in number, sit together, with their hands

uplifted, in the act of beating time on stretched skins,

while behind them is a tree with a bird on the top of

it.

In the same

picture the artist indicates the method of emu-stalking

and of fish-spearing.

No. 2 also

illustrates a variety of subjects : a native man in a

canoe catching a turtle; a pair of emus standing by

their nest, and a man throwing a spear at one of them ;

another man throwing his dowak at a large lizard ;

another in a canoe spearing a fish, which is very well

drawn; nine men are engaged in a mimic war-dance for the

amusement of a squatter and his wife, who are looking on

; they are brandishing boomerangs, clubs, and shields,

and one has a pipe in his mouth.

A tame emu is

standing by, doubtless belonging

* Paper read

before Anthropological Institute, 17th April 1871.

Fish-spearing, Figure 253,detail. |

Man in a canoe

catching a turtle, Figure 254, detail.

|

Page 258

to the station,

which stands in the background.

There is much

spirit in these drawings, the attitudes of some of the

figures, and the faces of some of the women, are very

good.

If carefully

examined, I think we cannot avoid the conclusion that

Tommy Barnes is a close observer, and is

possessed of some artistic skill, which, if cultivated,

would have enabled him to draw well.

These sketches

were hastily drawn, with no particular object in view,

and probably only for his own

amusement.

Page 298

They are also expert

in spearing fish at night from their canoes.

The canoe -which is

simply a sheet of bark cut off a tree with a bend in it is

allowed to drop silently down the stream ; a small fire is

lighted in the bow, on a raised piece of clay, of a peculiar

resinous wood, which bums with a clear, bright flame; the fish, attracted by the light, swim up to it,

and are immediately speared.

The canoes, being so

frail, require great steadiness in their management, though

on the Lower Murray I have seen them large enough to carry a

dozen men at once.

These large canoes are

cut off the giant swamp-gums.

They also snare the

wild turkey or bustard.

They approach as they

do when stealing on an emu ; but instead of a spear, they

carry a long light stick, at the extreme end of which is

tied a fluttering moth, as well as a strong running noose

hanging just below.

The bustard is so intent on

looking at the moth that he does not notice the noose, which

the cunning black at last succeeds in slipping over his

head.

They cook their large

game in ovens made in the following manner :

A hole is made in the

earth, and lined with stones ; in it they make a fierce

fijre, until the stones become almost red hot ; the

kangaroo, or what they intend to cook, is then placed in the

oven, on the top of which some more hot stones are placed,

and the whole covered with earth ; the heat of the stones

and the confined steam together cook the meat.

The natives, as a rule, are splendid swimmers, though there

are tribes living in dry country who will not go near the

water, and cannot swim a stroke ; but among River tribes

water is second nature children hardly able to walk swim

like ducks.

It is strange to watch a blackfellow catching ducks by

diving.

He drops down the

stream with merely a small portion of his head above water.

When he is close to

the flock, he quietly dives, and draws

one or two birds under the surface ; these he at once kills

and tucks them under his belt ; he then rises to the

surface, but only shows his nose ; in a moment he is down

again, and another duck or two disappear.

I have seen a black

take seven ducks in this manner without creating any

suspicion in the flock.

They are also expert

in noosing wild-fowl.

Page 300

Notes on Coopers

Creek

By ....

A small family of the

Yantruwunter go from the end of Strezelecki's Creek down to

Flood's Creek, and there meet natives of the Darling back

country.

I think that the native mentioned by Sturt as coming to his

camp (I think at Fort Grey) was probably one of this family.

Capt. Sturt mentions that he made signs of great waters to

the west or north-west, and also represented the paddling of

canoes ; I think this really represented the hauling in of a

net or "Yammcu."

I have seen such a pantomime, but I never saw a canoe or any

place where bark for a canoe had been stripped in Central

Australia.

Page 314

The largest article in the shape

of a covering of any sort which I have known them to

manufacture with the exception of the opossum rug

is a circular mat, about three

feet six inches in diameter, made out of rushes by the

lubras, on the banks of Lake Alexandrina, into which the

Murray empties, and used by them and not by the men.

These lubras also make

rafts out of the reeds which grow on the banks, and on them

go out sometimes miles on the lake to fish with nets. Both

men and women are very expert at diving and catching the

large fish, which lurk amongst the stones and timber at the

bottom of the

Page 315

rivers.

On the coast it was quite a

picturesque scene of a night, when the waters of some little

bay were lit up with scores of lights, which were

continually moving and forming a variety of fantastic

groups.

These lights were

pieces of blazing bark, carried by men, women, and children,

who, each armed with a spear formed of a straight pointed

young sapling, waded about the shallow waters in pursuit of

the fish brought in by the rising tide.

The blacks appear to

enjoy a certain immunity from the sharks ; for although I

have known numbers of men and women to swim in and out off a large quantity of fish from the schools of

schnapper, extending sometimes more than a mile each way,

which visit these coasts about December, and which schools

are invariably followed by a host of sharks, ever on the

watch to pick up the weakly fish, yet I never knew of an

instance where a black was injured.

That may, however,

most probably be owing to the sharks being in a manner

gorged at the time, as I have also known the blacks to swim

off to the stranded carcass of a whale to get the coarse

meat or Ereng as it is called when the sharks

have been almost as thick round it as flies on meat during

summer.

The blacks are very expert in

getting the schnapper alluded to.

For days previous,

scouts are posted on the various look-out places to give

notice of the approach of the fish ; and as soon as the

alarm is given, the greatest excitement prevails men,

women, and children rush recklessly into the water, swim

towards the school, cut off a lot of the fish, and then,

forming a semicircle, swim behind the fish and drive them

into shallow water, where they are dexterously and quickly

speared.

To give you an idea of

the quickness of the blacks, I can mention an instance in

which three blacks, another white, and myself, speared

upwards of thirty large schnappers in about twenty minutes.

Another common way of

catching mullet and whiting, and such sized fish, is, at the

time the tide is coming in, for a black to take a bough in

one hand, a spear in the other, and a piece of lithe

sarsaparilla root which abounds on the coast round his

neck ; he then gets behind a school of fish, moves the bough

with his hand, causing a shadow to fall on the water, before

which the fish rush away in terror, till he gradually gets

them into water from two to three feet deep, where he can

deal with them to a certainty, for every time he darts his

spear he is sure to strike a fish.

The black gives each a

bite at the back of the neck, and strings it through the

gills round his neck till he gets enough, when he walks

ashore, broils his fish, takes his meal, and under the shade

of a tree rests from his labors.

Page 320

I knew another instance where a

lubra called Charlotte, who had been taken away off the

coast when a girl by a party of sealers, and was living with

a man named Manson on an island called St. Peter's, about

fifty miles from Coffin's Bay, was on one occasion

proceeding in a boat on a sealing expedition to another

island, with her man, her two children, and another white

man named

Page 321

Jackson, when the boat

was upset by a sudden squall, and sank.

Charlotte and Jackson

rose to the surface, but neither Manson nor the children could be seen.

Charlotte swam about

for a considerable time in search of Manson and the

children, whom she was to rescue, if possible, at any

sacrifice ; but finding no signs of them, she turned to

Jackson and said " I will take you on my back and swim

ashore."

Jackson, however, was

equally generous ; and, although they were then out of sight

of land, refused her offer, saying that he would do the best

he could for himself.

Charlotte then got one

of the oars, which was floating close by, and stripping

herself of the woollen and cotton shirts which she had on,

she rolled them round the oar for Jackson to lay his breast

on.

They thus floated on

for some time, till the distance between them gradually

increased.

Charlotte eventually

lost sight of Jackson, and never saw him again.

On nearing the

coast, near Avoid Bay, where the surf breaks with awful

violence and a noise like thunder for miles off the land,

she met with great difficulties, practised and wonderful

swimmer as she was, and had to dive time after time

repeatedly, to prevent being dashed to pieces against the

rocks.

She succeeded at

length, after almost superhuman efforts, in reaching the

land about dusk, after being in the water from the early

part of a summer's day till then.

She assured me, and I

did not wonder at it, that when she made the land, and

attempted to walk up the beach, she fell down quite

exhausted.

To increase her

troubles, she shortly afterwards saw at a distance some of

the blacks belonging to that part of the coast, and being

afraid of being captured by them, concealed herself in the

scrub, and remained there all night.

Next morning she

started, and travelled cautiously on, till, finding some

cattle tracks, she followed the tracks till she came to the

herd, which were in charge of a white man, who kindly took

her to the hut, and clothed and fed her ; and, when suffi-

ciently recruited, she went into Port Lincoln, where I saw

her, and listened to her recital of the loss of her husband

and children, and her own narrow escape.

Page 381

THE ABORIGINES OF

TASMANIA

...

The natives of this place probably drew the principal part

of their food from the woods ; the bones of small animals,

such as opossums, squirrels, kangaroo-rats, and bandicoots,

were numerous round their deserted fire-places ; and the two

spears which they saw in the hands of the man were similar

to those used for hunting in other parts.

Many trees, also, were observed to be notched.

No canoes were ever seen, nor any trees so barked as to

answer that purpose." *

* An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales, by

Lieut.-CoL Ck>Uiiu, p. 480.

Page 401

WEAPONS,

IMPLEMENTS. ETC

The character of the weapons

made by the natives of Tasmania, the absence of ornament,

their using their clubs as missiles, and throwing stones

at their enemies when all their clubs were hurled, or when

they desired to keep their clubs for protection, indicate

a condition so much lower than that of the Australians,

that one is not unwilling, with Dr. Latham, to seek in

other lands than those from which Australia was peopled

for their origin.

Their implements were a vessel of bark, very neatly made,

for holding water, and baskets of different forms, like

those used by the natives of Australia.

The native names of the baskets were Treena, Tillti, and Trugkauna.

Large shells were kept for holding water and for conveying

it to the sick.

The natives necessarily had occasionally to cross rivers and arms of the sea.

Dove says that "the

contiguous islands of the Straits were frequently visited by

the tribes located on the northern coasts of Tasmania.

A species of bark or

decayed wood, whose specific gravity appears to be similar

to that of cork, provided them with the means of

constructing canoes.

The beams or logs were fastened

together by the help of rashes or thongs of skin.

These canoes

resembled, both in shape and in the mode by which they were

impelled and steered, the more elegant models in use among the Indians of America.

Their peculiar buoyancy secured them effectually against the usual

hazards of the sea."

From another source I

learn that when, during their excursions in the autumn,

which were supposed to be from west to east, and in the

spring from east to west, and they came to an arm of the

sea, or a large river, or a lake, they made a kind of raft,

somewhat like the catamarans of the people of Torres

Straits.

This raft was formed

of the trunks of two trees, about thirty feet in length, and

laid parallel to one another, and at a distance of five or

six feet.

The logs were kept

together by four or five smaller pieces of wood, laid across

at the ends, and fastened by slips of tough bark.

In the middle was a

cross timber of considerable thickness, and the whole was

interwoven with a kind of wicker-work, this raft was

propelled by paddles with amazing rapidity.

Such a vessel if

vessel it can be called would carry six or ten persons.

When it had served its

purpose, it was usually abandoned; and when Tasmania was

first colonized, the whites not unfrequently discovered

these rafts or their remains on the sea-shore, or on the banks of the rivers and lakes.

The names of the

canoes were Malanna,

Mungana, and Munghana.

Mr, Hull says that

there were formerly many accounts of the drowning of natives

who embarked in these catamarans for the purpose of visiting

the neighbouring islands.

Their bodies were

found on the beaches.

|

|