|

surfresearch.com.au

perkins : keauho, 1854 |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

Garrett & Co., New York, 1854.

Second edition, somewhat condensed with

five plates, printed in the same year.

Kessinger Publishing: Legacy Reprint Series,

2007.

In Chapter XX (1850?),

he visted Keahou (He'eia Bay) on the west (Kona) coast of the large island,

Hawaii.

On arrival, the

pleasure of their aquatic skills is demonstrated by welcoming native girls

in their outrigger canoes.

Perkins observed

surfriding at "on the northern side of the harbor at Keauho, the black

point of lava extends for a considerable distance into the sea".

Finney and Houston

(1996), page 29, record two ancient surfriding locations at Keahou, one

of of which is "Kaulu, 'ledge' ".

Realistically, and

replicating modern experience, the surfriders use the point for easy access

to the surf break: "children might be seen running out on this point

with their surf-boards.

Watching their

opportunity, they would plunge into the sea between two rollers, with exceedingly

nice judgment".

He also attempted

prone surfriding, on a four foot board and adopting native dress, under

instruction from two of the older girls.

This may not be

at the same surf break described above.

There are similar

accounts by Lt. Henry Wise

(1850) and the more famous accounts by Mark Twain (1866) and Jack London

(1907).

When paddling out,

the surfriders intially slip over the incoming lines of white water,"The

spent rollers we suffered to pass beneath us", but as they near the

breaking zone they are forced to duck-dive,"we dove beneath it, while

it broke and foamed above us".

Most commentators

only report the duck diving technique.

Perhaps uniquely,

he dramatically writes of the approach of a cresting wave from the viewpoint

of the surfrider:

"It is a strange

sight to see the horizon of vision contracting before you and rising rapiply

towards the zenith, until you look upon an impending wall of liquid blue,

imperceptibly melting to a delicate pea-green with a snowy crest.

There is a commingling

of beauty and sublimity, of stern majesty and power."

Perkins is less than

succesful in his exertions and concludes " the art of surf-riding

is not so simple as it would seem".

His session is terminated

by a severe wipe-out.

Rinsing with fresh water after swimming in the sea was a common practice across Polynesia.

On the east coast,

in the Hilo hinterland, Perkins observed young Hawaiian's leaping or diving

from a considerable height, encouraged by the tossing of coins into the

pool:

"We have often

amused ourselves by tossing 'reals' or 'medios' into the water, and seeing

the children leap from an elevation of twenty or thirty feet, and catch

them before they reach the bottom."

CHAPTER XX.

LOITERINGS IN A HAWAIIAN VILLAGE.

EARLY in the morning

the anchor was weighed, but the breeze being light, we did not reach Keauha

before ten o'clock.

As we entered

the harbor, the sight, was anything but tranquillizing to weak nerves.

We were steering

for an iron-bound shore, where the surf was beating with a noise like thunder,

and bursting upwards in sheets of foam.

Had the wind

failed us, it would have been unpleasant to anticipate consequences.

Though the entrance

was narrow, we had a commanding breeze that carried us safely in, where

we anchored and moored the schooner by ropes made fast to cocoanut-trees.

From the sensation

produced among the natives, I should judge that arrivals were unfrequent

at Keauho, for the adjoining rocks were covered with curious idlers, and

re-echoed theIr boisterous welcome.

The water, which

does not exceed two fathoms in depth, is beautifully transparent; and over

the white sandy bottom are scattered clusters of coral and shells.

Floating upon

it were canoes filled with girls, who paddled around us, laughing and singing

in high glee.

Frequently, when

the outriggers came in collision with each other, the occupant of one canoe,

by a dexterous movement, would capsize those of the other into the water;

a joke that was taken in good part, and some of these amphibious damsels

seemed to manifest a preference for the briny element.

Sometimes half

a dozen heads were dotting the surface on one side of the schooner; then,

by a simultaneous movement, all would disappear and presently be seen shooting

upwards on the opposite side.

They swam about,

plashing the brine in each other's faces, and when fatigued rested themselves

by clinging to the outriggers.

One of these

girls, perhaps fourteen years of age, possessed an ornament that might

excite the envy of our belles at home, and which so enhances female beauty.

This was the

most exquisite (indulge the word) head of hair I ever beheld in Polynesia.

While swimming,

it was either trailing behind her or hiding her face; but was only ...

Page 191

... seen to advantage

when its possessor was basking on shore, where she allowed it to float

loosely upon her shoulders.

Black, wavy,

and glossy, and unrivalled in fineness, its peculiar beauty was noticed

by all on board, from the owner to the sailor.

The juvenile

portion of the community seemed greatly to preponderate, and our deck was

soon encumbered with them.

Page 196

On the northern

side of the harbor at Keauho, the black point of lava extends for a considerable

distance into the sea, and in connection with a slight indentation in the

shore, it forms a cove, where

the surf rolls

heavily.

At any hour of

the day, children might be seen running out on this point with their surf-boards.

Watching their opportunity, they would plunge into the sea between two

rollers, with exceedingly nice judgment, reaching the wave at its culminating

point, and just as it was "combing," shoot in upon its crest, amid foam

and spray, with the velocity of a race-horse, and shouting in wild delight.

What the sled

is to the child at home, the papa, or surf-board, is to the juveniles of

Hawaii.

I determined

one morning to join them in their sport; and having signified my intention,

about twenty girls, of various ages, and a dozen buys, promised to give

me instruction.

I preferred confiding

myself to the management of the two oldest girls, who were more experienced.

A board, four feet in length, and rounded at both ends, was provided for

me.

This, when used,

is placed beneath the breast and held firmly between the extended arms,

at an angle of about fifteen degrees with the level of the sea.

The boys wore

malos, the girls, loose gowns; and not wishing to be encumbered with superfluous

"gear," I adopted the fashion of the former.

The shore receded

quickly, so that at a distance of ten yards we were beyond our depth.

The surf rolled

in heavily, and with my two instructresses on either side, I swam seaward.

The spent rollers

we suffered to pass beneath us, but as our distance from the shore increased,

they were not to be disregarded; and when we saw a wall of water rise up

before us, and come rolling in like an ...

Page 197

... avalanche,

we dove beneath it, while it broke and foamed above us.

I should have

said that I dove, for, like fishes, the girls could sink at will, and without

any apparent effort.

This peculiarity

I have also noticed among the pearl-divers of the Southern Ocean, who,

by giving a slight spring upward, sink easily, and turn beneath the surface.

I have frequently

attempted it, but without success, though by trial have remained under

water as long as expert divers.

The breakers were

frightful.

Though a good

swimmer, and familiar with winds and waves, I would never think of buffeting

voluntarily such a formidable array of cataracts without a host of guardians.

The roar was

incessant, and almost deafening; still, we kept on.

It is a strange

sight to see the horizon of vision contracting before you and rising rapiply

towards the zenith, until you look upon an impending wall of liquid blue,

imperceptibly melting to a delicate pea-green with a snowy crest.

There is a commingling

of beauty and sublimity, of stern majesty and power.

It is the mighty

bolt that shatters the groaning timbers of the ship, and scatters the fragments

upon the froth of its rage.

But my fair guardians

mocked its impotence.

With a laugh

and a shout, saying, "Lu kakou," (let us dive,) each clasped a hand,

and in tranquil depths we hid from the billow that thundered above us.

Having obtained

a suitable distance, we waited for a roller, and started upon its crest;

but the art of surf-riding is not so simple as it would seem.

With my companions

on either side, I flew rapidly along for a few seconds; but somehow or

other the wave always receded and left me in the lurch, while they shot

ahead in a sea of foam.

I sported in

this way for fifteen minutes, until a roller caught me as it broke, and

wrenching the board from my hands, whirled me along in every conceivable

attitude; and on recovering from the shock, I was compelled to abandon

my aquatic sports for the remainder of the day.

After bathing

in the sea, the girls always pour fresh water over each other, carefully

washing their dark tresses, for they say salt water impairs their beauty.

Page 199

All who have visited

Hilo concur in admiring its scenery.

...

The harbor, or

bay, derives its name from the town, and is situate on the N. E. side of

the island, forming a safe anchorage for vessels against all winds, except

from the northeast.

Near the southeast

shore there is a rocky islet covered with cocoanut-trees; and from this

towards the N. E. extends a shoal for a long distance so that the entrance

is on the western side, where the land is bold and the water deep.

During a strong

northeast wind, the sea rolls in heavily; and the shore is lined with breakers.

On these occasions

boats from vessels, instead of effecting a difficult landing on the western

side, which is most thickly settled, usually resort to the southern shore,

where a small stream affords them a secure retreat.

This is called

Waiakea, and waters the district of that name, constituting the southern

boundary of Hilo.

Page 202

Not far from its

mouth, and where it is intersected by the road passing through the town,

the course of the stream is among rocks, frequently broken by miniature

cascades and foaming rapids; in

one spot there

is a broad, deep pool, bounded on the left by a precipitous cliff.

During the latter

part of the afternoon, its banks are lined with boys and girls, who resort

here to bathe.

We have often

amused ourselves by tossing reals or medios into the water,

and seeing the children leap from an elevation of twenty or thirty feet,

and catch them before they reach the bottom.

|

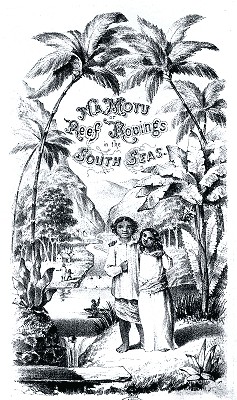

Na Motu: or, Reef-rovings in the South Seas. A Narrative of Adventures at the Hawaiian, Georgian and Society Islands; with Maps, Twelve Illustrations, and an Appendix. Relating to the Resources, Social and Political condition of Polynesia, and subjects of interest in the Pacific Ocean. Pudney and Russell, Publishers, Number 79 John Street, New York, 1854. |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |