|

surfresearch.com.au

basil hall : ceylon, peru, and india, 1832. |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basil_Hall

An edited version

of Hall's chapter Surf at Madras, with one illustration, was reprinted

in:

Atkinson, Samuel

Coate: Atkinson's Casket, Volume 10.

Sam. C. Atkinson,

1835, pages 131-132.

"This early predilection

of Basil Hall was soon gratified; for in 1802, when he had only reached

his fourteenth year, he was entered into the royal navy.

On leaving home,

'Now,' said his father, putting a blank book into one hand of the stripling,

and a pen into the other, 'you are fairly afloat in the world; you must

begin to write a journal.'

In 1814 he was promoted

to the rank of commander, and in 1817 to that of post-captain.

Pending the period

of advance from a lieutenancy, he was acting commander of the Theban

on the East India station, in 1813, when he accompanied its admiral, Sir

Samuel Hood, in a journey over the greater part of the island of Java.

On his return home

he was appointed to the command of the Lyra, a small gun brig that,

in 1816, formed part of the armament in the embassy of Lord Amherst to

China.

...

It is only necessary

to add to this account, that Captain Hall was a fellow of the Royal Societies

of London and Edinburgh, and a member of the Astronomical Society of London."

wikipedia.org:

The Raft of the Medusa

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Raft_of_the_Medusa

wikipedia.org:

Antonio de Ulloa

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonio_de_Ulloa

wikipedia.org:

Battle of Orthez

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Orthez

CHAPTER

III.

CEYLONESE CANOES

PERUVIAN BALSAS

THE FLOATING

WINDLASS OF THE COROMANDEL FISHERMEN.

The canoes of Ceylon, as far as I remember, are not described by any writer, nor have I met with many professional men who are aware of their peculiar construction, and of the advantages of the extremely elegant principle upon which they are contrived, though capable, I am persuaded, of being applied to various purposes of navigation.

Among the lesser

circumstances which appear to form characteristic points of distinction

between country and country, may

be mentioned

the head-dress of the men, and the form and rig of their boats.

An endless variety

of turbans, sheep-skin caps, and conical bonnets, distinguish the Asiatics

from the " Topee Wallas" or hat-

Page 69

wearers of Europe

; and a still greater variety exists amongst the boats of different nations.

My purpose just

now, however, is to speak of boats and canoes alone ; and it is really

most curious to observe, that their size, form, cut of sails, description

of oar and rudder, length of mast, and so on, are not always entirely regulated

by the peculiar climate of the locality, but made to depend on a caprice

which it is difficult to account for.

The boats of

some countries are so extremely ticklish, or unstable, and altogether without

bearings, that the smallest weight on one side more than on the other upsets

them.

This applies

to the canoes of the North American Indian, which require considerable

practice, even in the smoothest water, to keep them upright ; and yet the

Indians cross immense lakes in them, although the surface of those vast

sheets of fresh water is often as rough as that of any salt sea.

The waves, it is true, are not so long and high ; but they are very awkward to deal with, from their abruptness, and the rapidity with which they get up when a breeze sets in.

Page 70

On those parts

of the coast of the United States where the seasons are alternately very

fine and very rough, our ingenious friends, the Americans, have contrived

a set of pilot boats, which are the delight of every sailor.

This description

of vessel, as the name implies, must always be at sea, as it is impossible

to tell when her services may be required by ships steering in for the

harbour's mouth.

Accordingly,

the Baltimore clippers and the New York pilots defy the elements in a style

which it requires a long apprenticeship to the difficulties and discomforts

of a wintry navigation in a stormy latitude, duly to appreciate.

In the fine weather,

smooth water, and light winds of summer, these pilot-boats skim over the

surface with the ease and swiftness of a swallow, apparently just touching

the water with their prettily formed hulls, which seem too small to bear

the immense load of snow-white canvass swelling above them, and shooting

them along as if by magic, when every other vessel is lost in the calm,

and when even taunt-masted ships can barely catch a breath of air to fill

their sky-sails and

Page 71

royal studding-sails.

They are truly

" water witches;" for, while they look so delicate and fragile that one

feels at first as if the most moderate breeze must brush them from the

face of the ocean, and scatter to the winds all their gay drapery, they

can and do defy, as a matter of habit and choice, the most furious gales

with which the rugged " sea-board" of America is visited in February and

March.

I have seen a

pilot-boat off New York, in the morning, in a calm, with all her sails

set, lying asleep on the water, which had subsided into such perfect stillness

that we could count the seam of each cloth in the mirror beneath her, and

it became difficult to tell which was the reflected image, which the true

vessel.

And yet, within

a few hours, I have observed the same boat, with only her close- reefed

foresail set — no one visible on her decks — and the sea running mountains

high — threatening to swallow her up.

Nevertheless,

the beautiful craft rose as buoyantly on the back of the waves as any duck,

and, moreover, glanced along their surface, and kept so good a wind, that,

ere long, she shot a-head and

Page 72

weathered our

ship.

Before the day

was done, she could scarcely be distinguished from the mast-head to windward,

though we had been labouring in the interval under every sail we could

possibly carry without risk of the masts !

The balsas of

Peru, the catamarans and masullah boats of the Coromandel coast, and the

flying proas of the South Sea Islands, have all been described before,

and their respective merits dwelt upon by Cook, Vancouver, Ulloa, and others.

Each in its way,

and on its proper spot, seems to possess qualities which it is difficult

to communicate to vessels similarly

constructed at

a distance.

The boats of

each country, indeed, may be said to possess a peculiar language, understood

only by the natives of the countries to which they belong ; and, truly,

the manner in which the vessels of some regions behave under the guidance

of their respective masters, seems almost to imply that the boats themselves

are gifted with animal intelligence.

At all events,

their performance never fails to excite the highest professional admiration

of those whom expe-

Page 73

rience has rendered familiar with the difficulties to be overcome.

Long acquaintance

with the local tides, winds, currents, and other circumstances of the pilotage,

and the constant pressure

of necessity,

enable the inhabitants of each particular spot to acquire such masterly

command over their machinery, that no new comer, however well provided,

or however skilful generally, can expect to cope with them.

Hence it arises,

that boats of a man-of-war are found almost invariably inferior, in some

respects, to those of the port at which she touches.

The effect of

seeking to adapt our boats to any one particular place would be to render

them less serviceable upon the whole.

After remaining

some time at a place we might succeed in occasionally outsailing or outrowing

the natives ; but what sort of a figure would our boats cut at the next

point to which the ship might be ordered — say a thousand miles farther

from, or nearer to, the equator, where all the circumstances would inevitably

be found totally different from what they were at the last port ?

We should have

Page 74

to change again

and again, losing time at each place, and probably not gaining, after all,

any of the real advantages which the

natives long

resident on the spot alone know the art of applying to practice.

It has been somewhere

remarked, that when the human frame is compared with that of the inferior

animals, it is found that, while in swiftness it is beaten by one, in scent

by another, in strength by a third, yet does it contain by far the most

admirable and varied combination of all those qualities severally possessed

by the unintellectual animals.

Thus man, upon

the whole, is far better fitted than any of them for enduring the boundless

varieties of climate which distinguish the different quarters of the globe,

and for bringing into useful effort those inherent energies both of body

and mind with which he is gifted, and which in the end render him the undisputed

master of all other living things.

So it is (to

compare great things with small) in the case of the boats of ships of war

which are most ingeniously contrived to be useful in all climates, in all

seas, on every coast, and at all times and seasons.

Page 75

It is true they

seldom, if ever, match the boats of the ports at which they anchor, either

in sailing or in rowing.

But they are

invariably found to accomplish these purposes well enough for real service,

besides securing many other advantages

which the local

boats cannot command.

They are likewise

sufficiently well adapted to all seas and all weathers, and can either

carry heavy loads or sail quite light.

They are so strongly

built that they can take the ground without injury, and yet are not so

heavy as to be troublesome in handling. While they are strong enough to

bear the firing of a cannon in their bow, they are capacious enough to

carry water casks or provisions, or to disembark troops, without being

inconveniently cumbersome when stowed on the booms, or suspended from the

quarters.

Like the hardy

sailors who man them, they are rough and ready for any service, in any

part of the world, at any moment they may be required.

It is not likely that we shall ever essentially improve the build or equipment of our boats ; but it must always be useful to seafaring men to become acquainted

Page 76

with such practical

devices in seamanship as have been found to answer well ; especially if

they seem capable of being appropriated upon occasions which may possibly

arise in the course of a service so infinitely varied as that of the navy.

It is partly on this account, and partly as a matter of general curiosity,

that I think some mention of the canoes of Ceylon, and the balsas of

Peru, may interest

many persons for whom ordinary technicalities possess no charm.

At least there

appears to be an originality and neatness about both these contrivances,

and a correctness of principle, which we

are surprised

to find in connexion with perfect simplicity, and an absence of that collateral

knowledge which we are so apt to fancy belongs only to more advanced stages

of civilisation and philosophical instruction.

The hull or body

of the Ceylonese canoe is formed, like that of Robinson Crusoe's, out of

the trunk of a single tree, wrought in its middle part into a perfectly

smooth cylinder, but slightly flattened and turned up at both ends, which

are made exactly alike.

It is hollowed

out in the usual

Page 77

way, but not cut

so much open at top as we see in other canoes, for considerably more than

half of the outside part of the cylinder or barrel is left entire, with

only a narrow slit, eight or ten inches wide, above.

If such a vessel

were placed in the water it would possess very little stability, even when

not loaded with any weight on its upper edges.

But there is

built upon it a set of wooden upper works, in the shape of a long trough,

extending from end to end ; and the top-heaviness of this addition to the

hull would instantly overturn the vessel, unless some device were applied

to preserve its upright position.

This purpose

is accomplished by means of an out-rigger on one side, consisting of two

curved poles, or slender but tough spars, laid across the canoe at right

angles to its length, and extending to the distance of twelve, fifteen,

or even twenty feet, where they join a small log of buoyant wood, about

half as long as the canoe, and lying parallel to it, with both its ends

turned up like the toe of a slipper, to prevent its dipping into the waves.

The inner ends

of these transverse

Page 78

poles are securely

bound by thongs to the raised gunwales of the canoe.

The out-rigger

— which, it may be useful to bear in mind, is always kept to windward —

acting by its weight at the end of so long a lever, prevents the vessel

from turning over by the pressure of the sail ; or, should the wind shift

suddenly, so as to bring the sail a-back, the buoyancy of the floating

log would prevent the canoe from upsetting on that side by retaining the

out-rigger horizontal.

So far the ordinary

purpose of an out-rigger is answered ; but there are other ingenious things

about these most graceful of all boats which seem worthy of the attention

of professional men.

The mast, which

is very taunt, or lofty, supports a lug-sail of immense size, and is stepped

exactly in midships, that is, at the same distance from both ends of the

canoe.

The yard, also,

is slung precisely in the middle ; and while the tack of the sail is made

fast at one extremity of the hull, the opposite corner, or clew, to which

the sheet is attached, hauls aft to the other end.

Shrouds extend

from the mast-head to the gunwale of the canoe ;

Page 79

beside which,

slender backstays are carried to the extremity of the out-rigger; and these

ropes, by reason of their great spread,

give such powerful

support to the mast, though loaded with a prodigious sail, that a very

slender spar is sufficient.

If I am not mistaken,

some of these canoes are fitted with two slender masts, between which the

sail is triced up, without a yard.

In the vignette

title-page to this volume, the canoes are taken from a drawing by the late

Mr. Daniell.

The back-ground

of Ceylon, with Adam's Peak in the centre, distant upwards of seventy miles,

is from a sketch I made on board his Majesty's ship Minden.

The method of

working the sails of these canoes is as follows.

They proceed

in one direction as far as may be deemed convenient, and then, without

going about, or turning completely round as we do, they merely change the

stern of the canoe into the head, by shifting the tack of the sail over

to leeward, and so converting it into the sheet — while the other clew,

being shifted up to windward, becomes the tack.

Page 80

As soon as these

changes have been made, away spins the little fairy bark on her new course,

but always keeping the same side,

or that on which

the out-rigger is placed to windward.

It will be easily

understood that the pressure of the sail has a tendency to lift the weight

at the extremity of the out-rigger above the surface of the water.

In sailing along,

therefore, the log just skims the tops of the waves, but scarcely ever

buries itself in them, so that little or no interruption to the velocity

of the canoe is caused by the out-rigger.

When the breeze

freshens so much as to lift the weight higher than the natives like, one,

and sometimes two of them, walk out on

the horizontal

spars, so as to add their weight to that of the out-rigger.

In order to enable

them to accomplish this purpose in safety, a " man rope," about breast

high, extends over each of the spars from the mast to the backstays.

Of all the ingenious native contrivances for turning small means to good account, one of the most curious, and, under certain circumstances, perhaps the most useful, is the Balsa, or raft of South Ame-

Page 81

rica, or, as it

is called on some parts of the coast, the catamaran.

This singular

vessel is not only very curious in the eyes of persons who have attended

at all to such things as amateurs, but is calculated also to furnish some

useful hints to professional seamen.

The simplest

form of the raft, or Balsa, is that of five, seven, or nine large beams

of a very light wood — say from fifty to sixty feet long — arranged side

by side, with the longest spar placed in the centre.

These logs are

firmly held together by cross bars, lashings, and stout planking near the

ends.

They vary from

fifteen to twenty, and even thirty feet in width.

I have seen some

at Guayaquil of an immense size, formed of logs as large as a frigate's

foremast.

These are intended

for conveying goods to Paita, and other places along shore.

The Balsa generally

carries only one large sail, which is hoisted to what we call a pair of

sheers, formed by two poles crossing at the top, where they are lashed

together.

It is obvious,

that it would be difficult to step a mast securely to a raft in the manner

it is done in a

Page 82

ship.

It is truly astonishing

to see how fast these singular vessels go through the water ; but it is

still more curious to observe how accurately they can be steered, and how

effectively they may be handled in all respects like any ordinary vessel.

The method by

which the Balsas are directed in their course is extremely ingenious, and

is that to which I should wish to call the attention of sailors, not merely

as a matter of curiosity (although on this score, too, it certainly has

great interest), but chiefly from its practical utility in seamanship.

No officer can

tell how soon he may be called upon to place his crew on a raft, should

his ship be wrecked ; and yet, unless he has been previously made aware

of some method of steering it, no purpose may be answered but that of protracting

the misery of the people under his charge.

We all recollect

the horrid scenes which took place on the raft which left the French frigate

Meduse, on the coast of Africa, in 1816 ; and yet it is perfectly

obvious, from the state of the wind and weather, that if any one of that

ill-fated party had been aware of the

Page 83

principle upon

which the South American Balsas are steered, they might easily have reached

the land in a few hours, and all

the lives, so

horribly sacrificed, might have been saved.

Nothing can be

conceived more simple, or more easy of application, than the South American

contrivance.

Near both ends

of the centre spar there is cut a perpendicular slit, about a couple of

inches wide by one or two feet in length.

Into each of

these holes a broad plank, called Guaras by the natives, is inserted in

such a way that it may be thrust down to the depth often or twelve feet;

or, at pleasure, it may be drawn up entirely.

The slits are

so cut, that, when the raft is in motion, the edges of these planks shall

meet the water ; or, in mathematical language, their planes are parallel

with the length of the spars.

It is clear,

that if both the Guaras be thrust quite down, and there held fast in a

perpendicular direction, they will ofier a broad surface towards the side,

and thus, by acting like the leeboards of a river barge, or the keel of

a ship, prevent the Balsa from drifting

Page 84

sidewise or dead

to leeward.

But while these

Guaras serve the purpose of a keel, they also perform the important duty

of a rudder, the rationale of which every sailor will understand, upon

considering the effect which must follow upon pulling up either the Guara

in the bow or that in the

stern.

Suppose, when

the wind is on the beam, the foremost one drawn up ; that end of the raft

will instantly have a tendency to drift to leeward from the absence of

the lateral support it previously received from its Guara or keel at the

bow ; or, in sea language, the Balsa will immediately " fall off," and

in time she will come right before the wind.

On the other

hand, if the foremost Guara be kept down while the sternmost one is drawn

up, the Balsa's head, or bow, will gradually come up towards the wind,

in consequence of that end retaining its hold of the water by reason of

its Guara, while the stern end, being relieved from its lateral support,

drifts to leeward.

Thus, by judiciously

raising or lowering; one or both the Guaras, the raft may not only be steered

with the greatest nicety, but may be tacked or wore, or other-

Page 85

wise directed, with a degree of precision which appears truly wonderful to those who see it for the first time ; nor is this contrivance less a subject of admiration after the principles have been studied.

I never shall

forget the sensation produced in a ship I commanded one evening on the

coast of Peru, as we steered towards the roadstead of Payta, so celebrated

in Anson's voyage, and beheld an immense Balsa dashing out before the land

wind, and sending a snowy wreath of foam before her like that which curls

up before the bow of a frigate in chase.

As long as she

was kept before the wind, we could understand this in some degree ; but

when she hauled up in order to round the point, and having made a stretch

along shore, proceeded to tack, we could scarcely believe our eyes.

Had the celebrated

Flying Dutchman sailed past us, our wonder could hardly have been excited

more.

In Ulloa's interesting

voyage to South America, a minute account is given of the Balsa, which

I recommend to the attention of professional men.

He winds up in

these words : —

Page 86

" Had this method of steering been sooner known in Europe, it might have alleviated the distress of many a shipwreck, by saving numbers of lives ; as in 1730, the Genoesa, one of his Majesty's frigates, being lost on the Vibora, the ship's company made a raft ; but committing themselves to the waves without any means of directing their course, they only added some melancholy minutes to their existence." — Ulloa, book iv. chap. 9.

I have lately

seen a model of a raft devised some years ago, expressly in imitation of

the South American Balsa, by Rear-Admiral Sir Frederick Maitland, K.C.B.,

to be made out of the spare spars with which every ship of war is supplied.

He proposes to

form each of the Guaras, or steering boards, of two of the ship's company's

mess tables joined together by gratings and planks.

But he sees no

reason why these should be limited in number, and thinks that they might

perhaps be usefully distributed along the entire length of the centre spar,

so as effectually to prevent leeway or drift.

In this manner,

Sir Frederick is of opinion that a raft, capable of carrying a

Page 87

whole ship's crew,

might be navigated for a considerable distance with ease and security.

And I am glad

to find myself anticipated by an authority deservedly so high with the

profession, in this practical illustration of an idea that has appeared

to me extremely feasible, from the first moment I saw the Peruvian Balsas.

It will generally

be found well worth an officer's attention to remark in what manner the

natives of any coast, however rude they may be, contrive to perform difficult

tasks.

Such things may

be very simple and easy for us to execute, when we have all the appliances

and means of our full equipment at command ; but as circumstances may often

occur to deprive us of many of those means, and thus, virtually, to reduce

us to the condition of the natives, it becomes of consequence to ascertain

how necessity, the venerable mother of invention, has taught people so

situated to do the required work.

For example,

it is generally easy for a ship of war to pick up her anchor with her own

boats; but it will sometimes happen that the launch and other large boats

may be stove, and

Page 88

then it may prove of consequence to know how a heavy anchor can be weighed without a boat at all.

We happened, in

his Majesty's ship Minden, to run upon the Coleroon shoal, off the

mouth of the great river of that name, about a hundred miles south of Madras.

After laying

out a bower anchor, and hauling the ship off, we set about preparing the

boats to weigh it in the usual way.

But the master-attendant

of Porto Novo, who had come off to our assistance with a fleet of canoes

and rafts, suggested to Sir Samuel Hood, that it might be a good opportunity

to try the skill of the natives, who were celebrated for their expertness

in raising great weights from the bottom.

The proposal

was one which delighted the admiral, who enjoyed every thing that was new.

He posted himself

accordingly in his barge near the spot, but he allowed the task to be turned

over entirely to the black fellows, whom he ordered to be supplied with

ropes, spars, and any thing else they required from the ship.

The officers

and sailors, in imitation of their chief, clustered themselves

Page 89

in wondering groups in the rigging, in the chains, and in the boats, to witness the strange spectacle of a huge bower anchor, weighing nearly four tons, raised of the ground by a set of native fishermen, possessed of no canoe larger than the smallest gig on board.

The master-attendant

stood interpreter, and passed backwards and forwards between the ship and

the scene of operations — not to direct, but merely to signify what things

the natives required for their purpose.

They first begged

us to have a couple of spare topmasts and topsail-yards, with a number

of smaller spars, such as top-gallant-masts and studding-sail booms.

Out of these

they formed, with wonderful speed, an exceedingly neat cylindrical raft,

between two and three feet in diameter.

They next bound

the whole closely together by lashings, and filled up all its inequalities

with capstan-bars, hand- spikes, and other small spars, so as to make it

a compact, smooth, and uniform cylinder from end to end.

Nothing could

be more dextrous or seaman-like than the style in which these fellows swam

about and passed

Page 90

the lashings ; in fact, they appeared to be as much at home in the water as our sailors were in the boats or in the rigging.

A stout seven-inch

hawser was now sent down by the buoy-rope, and the running clinch or noose

formed on its end, placed over the flue of the anchor in the usual way.

A couple of round

turns were then taken with the hawser at the middle part of the cylindrical

raft, after it had been drawn up as tight as possible from the anchor.

A number of slew

ropes, I think about sixty or seventy in all, were next passed round the

cylinder several times, in the opposite direction to the round turns taken

with the hawser.

Upwards of a hundred

of the natives now mounted the raft, and, after dividing themselves into

pairs, and taking hold of the slew ropes in their hands, pulled them up

as tight as they could.

By this effort

they caused the cylinder to turn round till its further revolutions were

stopped by the increasing tightness of the hawser, which was wound on the

cylinder as fast as the slew ropes were wound off it.

Page 91

When all the ropes

had been drawn equally tight, and the whole party of men had been ranged

along the top in an erect posture, with their faces all turned one way,

a signal was given by one of the principal natives.

At this moment

the men, one and all, still grasping their respective slew ropes firmly

in their hands, and without bending a joint in their whole bodies, fell

simultaneously on their backs, flat on the water !

The effect of

this sudden movement was to turn the cylinder a full quadrant, or one quarter

of a revolution.

This, of course,

brought a considerable strain on the hawser fixed to the anchor.

On a second signal

being given, every alternate pair of men gradually crept up the spars by

means of their slew ropes, till one-half of the number stood once more

along the top of the cylinder, while the other half of the party still

lay flat on the water, and by their weight prevented the cylinder rolling

back again.

When the next signal was given, those natives, who had regained their original position on the top of the cylinder, threw themselves down once more, while those

Page 92

who already lay

prostrate gathered in the slack of their slew ropes with the utmost eagerness

as the cylinder revolved another

quarter of a

turn.

It soon became

evident that the anchor had fairly begun to rise off the ground, for the

buoy-rope, which at first had been bowsed taught over the stern of our

launch, became quite slack.

But Sir Samuel

would not allow his people in the launch to assist the natives, as he felt

anxious to see whether or not they could accomplish single-handed what

they had undertaken.

Accordingly,

the slack of the buoy-rope merely was taken in by the launch's crew.

I forget how many

successive efforts were made by the natives before the anchor was lifted

; but in the end it certainly was raised completely off the ground by their

exertions alone.

The natives,

however, complained of the difficulty being much greater than they had

expected or had ever encountered before, in consequence of the great size

of our anchor.

In fact, when

at length they had wound the hawser on the cylinder so far that it carried

the full weight, the

Page 93

whole number of the natives lay stretched on the water in a horizontal position, apparently afraid to move, lest the weight, if not uniformly distributed amongst them, might prove too great, and the anchor drop again to the bottom by the returning revolutions of the cylinder.

When this was

explained to Sir Samuel Hood, he ordered the people in the launch to bowse

away at the buoy-rope.

This proved a

most seasonable relief to the poor natives, who, however, declared, that

if it were required, they would go on, and

bring up the

anchor fairly to the water's edge.

As the good-natured

admiral would not permit this, the huge anchor, cylinder, natives, launch,

and all, were drawn into deep water where the ship lay.

The master attendant

now explained to the natives that they had nothing more to do than to continue

lying flat and still on the

water, till the

people on board the ship, by heaving in the cable, should bring the anchor

to the bows, and thus relieve them of their burden.

The officer of

the launch also was instructed not to slack the buoy-rope till the cable

had got the full weight

Page 94

of the anchor, and the natives required no farther help.

Nothing could

be more distinctly given than these orders, so that I cannot account for

the panic which seized some of the natives when close to the ship.

Whatever was

the cause, its effect was such that many of them let go their slew-ropes,

and thus cast a disproportionate share of

burden on the

others, whose strength, or rather weight, proving unequal to counterpoise

the load, the cylinder began to turn back again.

This soon brought

the whole strain, or nearly the whole, on the stern of the launch, and

had not the tackle been smartly let go, she must have been drawn under

water and swamped.

The terrified

natives now lost all self-possession, as the mighty anchor shot rapidly

to the bottom.

The cylinder

of course whirled round with prodigious velocity as the hawser unwound

itself, and so suddenly had the catastrophe occurred, that many of the

natives, not having presence of mind to let go their slew-ropes, held fast

and were of course whisked round and round several times, alternately under

water

Page 95

beneath the cylinder and on the top of it, not unlike the spokes of a coach-wheel wanting the rim.

The admiral was

in the greatest alarm, lest some of these poor fellows should get entangled

with the ropes and be drowned, or be dashed against one another, and beaten

to pieces against the cylinder.

It was a great

relief, therefore, to find that no one was in the least degree hurt, though

some of the natives had been soused most

soundly, or,

as the Jacks said, who grinned at the whole affair, " keel-hauled in proper

style."

In a certain sense, then, this experiment may be said to have failed ; but enough was done to shew the feasibility of the method, which, under the following modifications proposed by our great commander — who was one of the best sailors that ever swam the ocean — I have no doubt might be rendered exceedingly effective on many occasions.

" In the first place," said Sir Samuel, " you must observe, youngsters, that this device of the natives is neither more nor less than a floating windlass, where the

Page 96

buoyant power

of the timber serves the purpose of a support to the axis.

The men fixed

by the slew-ropes to the cylinder represent the handspikes or bars by which

the windlass is turned round, and

the hawser takes

the place of the cable.

But," continued

he, " there appears to be no reason why the cylinder should be made equally

large along its whole length; and were I to repeat this experiment, I would

make the middle part, round which the hawser was to be passed, of a single

topmast, while I would swell out the ends of my cylinder or raft to three

or four feet in diameter.

In this way a

great increase of power would evidently be gained by those who worked the

slew-ropes.

In the next place,"

said the admiral, "it is clear that either the buoy-rope, or another hawser

also fastened to the anchor, as a 'preventer,' ought to be carried round

the middle part of the cylinder, but in the opposite direction to that

of the weighing hawser. This second hawser should be hauled tight round

at the end of each successive quarter turn gained by the men.

If this were

Page 97

done, all tendency

in the cylinder to turn one way more than the other would be prevented

; for each of the hawsers would bear an equal share of the weight of the

anchor, and being wound upon the raft in opposite directions, would of

course counteract each other's tendency to slew it round.

The whole party

of men, instead of only one -half of them, might then mount the spars ;

and thus their united strength could be exerted at each effort, and in

perfect security, against the formidable danger of the cylinder whirling

back by the anchor gaining the

mastery over

them, and dropping again to the bottom.

But without using

their clumsy, though certainly very ingenious, machinery of turning men

into hand- spikes, I think," said he, " we might construct our floating

windlass in such a way that a set of small spars, studding-sail booms,

for instance, might be inserted at right angles to its length, like the

bars of a capstan, and these, if swifted together, could be worked from

the boats, without the necessity of any one going into the water."

Page 98

While speaking

of the dexterity of the natives of India, I may mention a feat which interested

us very much.

A strong party

of hands from the ship were sent one day to remove an anchor, weighing

seventy -five hundred -weight, from one part of Bombay dock-yard to another,

but, from the want of some place to attach their tackle to, they could

not readily transport it along the wharf.

Various devices

were tried in vain by the sailors, whose strength, if it could have been

brought to bear, would have proved much more than enough for the task.

In process of

time, no doubt, they would have fallen upon some method of accomplishing

their purpose ; but while they were discussing various projects, one of

the superintendants said, he thought his party of native coolies or labourers

could lift the anchor and carry it to any part of the yard.

This proposal

was received by our Johnnies with a loud laugh ; for the numbers of the

natives did not much exceed their own, and the least powerful of the seamen

could readily, at least in his own estimation, have demolished half-a-

Page 99

dozen of the strongest of these slender-limbed Hindoos.

To work they went,

however, while Jack looked on with great attention.

Their first operation

was to lay a jib-boom horizontally, and nearly along the shank of the anchor.

This being securely

lashed to the shank and also to the stock, the whole length of the spar

was crossed at right angles by capstan bars, to the ends of which as many

handspikes as there was room for were lashed also at right angles.

In this way,

every cooly of the party could obtain a good hold, and exert his strength

to the greatest purpose.

I forget how

many natives were applied to this service; but in the course of a very

few minutes their preparations being completed, the ponderous anchor was

lifted a few inches from the ground, to the wonder and admiration of the

British seamen, who cheered

the black fellows,

and patted them on the back as they trotted along the wharf with their

load, which appeared to oppress them no more than if it had been the jolly-boat's

grapnell !

Page 100

CHAPTER

IV.

THE

SURF AT MADRAS.

From Ceylon we

proceeded after a time to Madras roads, where we soon became well acquainted

with all the outs and ins of the celebrated surf of that place.

This surf, after

all, is not really higher than many which one meets with in other countries

; but certainly it is the highest and most troublesome which exists as

a permanent obstruction in front of a great commercial city.

The restless

ingenuity and perseverance of man, however, have gone far to surmount this

difficulty; and now the passage to and from the beach at Madras offers

hardly any serious interruption to the intercourse.

Still, it is

by no means an agreeable operation to pass through the surf under any circumstances

; and occasionally, during the north-east monsoon, it is attended with

some degree ...

Page 101

... of danger.

For the first

two or three times, I remember thinking it very good sport to cross the

surf, and sympathised but little with the anxious expressions of some older

hands who accompanied me.

The boat, the

boatmen, their curious oars, the strange noises they made, and the attendant

catamarans to pick up the passengers

if the boat upsets,

being all new to my eyes, and particularly odd in themselves, so strongly

engaged my attention, that I had no leisure to think of the danger till

the boat was cast violently on the beach.

The very first

time I landed, the whole party were pitched out heels over head on the

shore.

I thought it

a mighty odd way of landing; but supposing it to be all regular and proper,

I merely muttered with the sailor whom the raree showman blew into the

air, — " What the devil will the fellows do next ? " and scrambled up the

wet sand as best I might.

The nature of

this risk, and the methods adopted by the natives to prevent accidents,

are easily described.

The surf at Madras

consists of two distinct lines of breakers on the beach, running parallel

...

Page 102

... to each other

and to the shore.

These foaming

ridges are caused by a succession of waves curling over and breaking upon

bars or banks, formed probably by the reflux action of the sea carrying

the sand outwards.

The surf itself,

unquestionably, owes its origin to the long send of the ocean-swell coming

across the Bay of Bengal, a sweep of nearly five hundred miles, from the

coasts of Arracan, the Malay peninsula, and the island of Sumatra — itself

a continent.

This huge swell

is scarcely perceptible far off in the fathomless Indian sea ; but when

the mighty oscillation — for it is nothing more — reaches the shelving

shores of Coromandel, its vibrations are checked by the bottom.

The mass of waters,

which up to this point had merely sunk and risen, that is, vibrated without

any real progressive motion, is then driven forwards to the land, where,

from the increasing shallowness, it finds less and less room for its "

wild waves' play," and

finally rises

above the general level of the sea in threatening ridges.

I know few things

more alarming to nautical nerves than the sudden and mysterious "lift of

...

Page 103

... the swell,"

which hurries a ship upwards when she has chanced to get too near the shore,

and when, in consequence of the

deadness of the

calm, she can make no way to seaward, but is gradually hove nearer and

nearer to the roaring surge.

At last, when

the great ocean wave approaches the beach, and the depth of water is much

diminished, the velocity of so vast a mass sweeping along the bottom, though

greatly accelerated, becomes inadequate to fulfil the conditions of the

oscillation; and it has no resource but to curl into a high and toppling

wave.

So that this

moving ridge of waters, after careering forwards with a front high in proportion

to the impulse behind, and, for a length of time regulated by the degree

of abruptness in the rise of the shore, at last dashes its monstrous head

with a noise extremely like thunder along the endless coast.

Often, indeed, when on shore at Madras, have I lain in bed awake, with open windows, for hours together, listening, at the distance of many a league, to the sound of these waves, and almost fancying I could ...

Page 104

... still feel

the tremor of the ground, always distinctly perceptible near the beach.

When the distance

is great, and the actual moment at which the sea breaks ceases to be distinguishable,

and when a long range of coast is within hearing; the unceasing roar of

the surf in a serene night, heard over the level plains of the Carnatic

shore, is wonderfully interesting.

Long afterwards,

when within about five miles in a direct line from the Falls of Niagara,

I remember thinking the continuous sound of the cataract not unlike that

produced by the surf at Madras.

What rendered

the similarity greater, was the occasional variation in the depth of the

note, caused by the fitful nature of the intervening flaws of wind, just

as the occasional coincidence in the dash of a number of waves, or their

discordance as to the time of their occurrence, or finally, some variation

in the strength of the land-breeze, broke the continuity of sound from

the shore.

But it must fairly be owned, that there is nothing either picturesque or beautiful — though there may be a touch of the ...

Page 105

... Sublime —

in the surf when viewed from a boat tossing about in the middle of its

deafening clamour, and when the spectator is threatened every instant to

be sent sprawling and helpless amongst the expectant sharks which accompany

the masullah boats with as much regularity, though for a very different

purpose, as the catamarans.

These primitive

little life-preservers, which are a sort of satellites attending upon the

great masullah or passage-boat, consist of two or three small logs of light

wood fastened together, and capable of supporting several persons.

In general, however,

there is but one man upon each, though on many there are two.

Although the

professed purpose of these rafts is to pick up the passengers of such boats

as may be unfortunate enough to get upset in the surf, new comers from

Europe are by no means comforted in their alarm on passing through the

foam, to be assured that, in the possible event of their boat being capsised,

the catamaran men may probably succeed in picking them up before the

sharks can find

time to nip off their legs !

Page 106

I grievously suspect that it is the cue both of the boatmen and of these wreckers to augment the fears of all Johnny Raws ; and possibly the sly rogues occasionally produce slight accidents, in order to enhance the value of their services, and thereby to strengthen their claim to the two or three fanams which they are enchanted to receive from you as a toll.

Any attempt to

pass the surf in an ordinary boat is seldom thought of.

I remember hearing

of a naval officer who crossed in his jolly-boat once in safety, but on

a second trial he was swamped, and both

he and his crew

well-nigh drowned.

The masullah

boats of the country resemble nothing to be seen elsewhere.

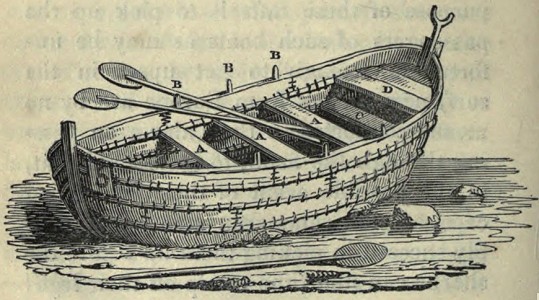

DIAGRAM

Page 107

They are distinguished

by flat bottoms, perpendicular sides, and abruptly pointed ends, being

twelve or fourteen feet long by five or six broad, and four or five feet

high.

Not a single

nail enters into their construction, all the planks being held together

by cords or lacings, which are applied in the following manner.

Along the planks,

at a short distance from the edge, are bored a set of holes, through which

the lacing or cord is to pass.

A layer of cotton

is then interposed between the planks, and along the seam is laid a flat

narrow strip of a fibry and tough kind of wood.

The cord is next

rove through the holes and passed over the strip, so that when it is pulled

tight the planks are not only drawn into as close contact as the interposed

cotton will allow of, but the long strip is pressed against the seam so

effectually as to exclude the water.

The wood of which these boats are constructed is so elastic and tough, that when they take the ground, either by accident or in the regular course of service, the part which touches yields to the pressure without breaking, and bulges inwards al-

Page 108

most as readily

as if it were made of shoe-leather.

Under similar

circumstances, an ordinary boat, fitted with a keel, timbers, and planks

nailed together, not being pliable, would be shivered to pieces.

At the after or

sternmost end, a sort of high poop-deck, passes from side to side, on which

the steersman takes his post.

He holds in his

hand an oar or paddle, which consists of a pole ten or twelve feet long,

carrying at its extremity a circular disc of wood about a foot or a foot

and a half in diameter.

The oars used

by the six hands who pull the masullah boat are similar to that held by

the steersman, who is always a person of long experience and known skill,

as well as courage and coolness — qualities indispensable to the safety

of the passage when the surf is high.

The rowers sit

upon high thwarts, and their oars are held by (a) grummets or rings made

of rope, to pins (b), inserted in the gunwale, so that they can be let

go and resumed at pleasure, without risk of being lost.

The passengers,

wretched victims ! seat themselves on a cross bench (c), about a foot lower

than the seats of the ...

Page 109

... rowers, and close in front of the raised poop or steersman's deck (d), which is nearly on a level with the gunwale.

The whole process

of landing, from the moment of leaving the ship till you feel yourself

safe on the crown of the beach, is as disagreeable as can be ; and I can

only say for myself, that every time I crossed the surf it rose in my respect.

At the eighth

or tenth transit I began really to feel uncomfortable ; at the twentieth,

I felt considerable apprehension of being well ducked ; and at about the

thirtieth time of crossing, I almost fancied there was but little chance

of escaping a watery grave, with sharks for sextons, and the wild surf

for a dirge !

The truth is,

that at each successive time of passing this formidable barrier of surf,

we become better and better acquainted with the dangers and the possibilities

of accident — somewhat on the principle, I suppose, that a veteran soldier

is said to be by no means so indifferent as a raw recruit is to the whizzing

of shot about his ears.

However this may be, as all persons intending to go ashore at Madras must ..

Page 110

... pass through

the surf, they step with what courage they can muster into their boat alongside

the ship, anchored in the roads a couple of miles off, in consequence of

the water being too shallow for large vessels.

The boat then

shoves off, and rows to the " back of the surf," where it is usual to let

go a grapnel, or to lie on the oars till the masullah boat comes out.

The back of the

surf is that part of the road-stead lying immediately beyond the place

where the first indication is given of the

tendency in the

swell to rise into a wave ; and no boat not expressly fitted for the purpose

ever goes nearer to the shore, but lies off till the "bar-boat" makes her

way through the surf, and lays herself alongside the ship's boat.

A scrambling

kind of boarding operation now takes place, to the last degree inconvenient

to ladies and other shore-going persons not accustomed to climbing.

As the gunwale

of the masullah boat rises three or four feet above the water, the step

is a long and troublesome one to make, even by those who are not encumbered

with petticoats — those sad impediments to loco-

Page 111

motion — devised by the men, as I heard a Chinaman remark, expressly to check the rambling propensities of the softer sex, always too prone, he alleged, to yield to wandering impulses !

Be this, also,

as it is ordained, I know to my cost, in the shape of many a broken shin,

that even gentlemen bred afloat may contrive to slip in removing from one

boat to the other, especially if the breeze be fresh, and there be what

mariners call a "bubble of a sea" — a term redolent in most imaginations

with squeamishness and instability of stomach and footing.

In a little while,

however, all the party are tumbled, or hoisted into the masullah boat,

where they seat themselves on the cross

bench, marvellously

like so many culprits on a hurdle on their way to execution !

Ahead of them

roars and boils a furious ridge of terrific breakers, while close at their

ears behind, stamps and bawls, or rather yells, the steersman, who takes

this method of communicating his wishes to his fellow-boatmen, not in the

calm language of an officer intrusted with the lives of so many harmless

and helpless ...

Page 112

... individuals,

but in the most extravagant variety of screams that ever startled the timorous

ear of ignorance.

In truth, no

length of experience can ever reconcile any man, woman, or child, to these

most alarming noises, which, if they do not

really augment

the danger, certainly aggravate the alarm, and add grievously to their

feeling of insecurity on the part of the devoted passengers.

I need scarcely

say, that the steersman is the absolute master for the time being, as every

skipper ought to be, whether he wear a coat and epaulettes, or be limited

in his vestments, as these poor masullah boatmen are, to the very minimum

allowance of inexpressibles.

This not-absolutely-naked

steersman, then, as I have before mentioned, stands on his poop, or quarter-deck,

just behind the miserable passengers, whose heads reach not quite so high

as his knees.

His oar rests

in a crutch on the top of the stern-post, and not only serves as a rudder,

but gives him the power to slew or twist the boat round with considerable

rapidity, when aided by the efforts of the rowers.

It is ...

Page 113

... necessary

for the steersman to wait for a favourable moment to enter the surf, otherwise

the chances are that the boat

will be upset,

in the manner I shall describe presently.

People are frequently

kept waiting in this way for ten or twenty minutes, at the back of the

surf, before a proper opportunity presents itself.

During all this

while the experienced eye of the veteran skipper abaft glances backwards

and forwards from the swell rolling in from the open sea, to the surf which

is breaking close to him.

From time to

time he utters a half word to his crew, with that kind of faint interrogative

tone in which a commanding officer indulges

when he is sure

of acquiescence on the part of those under him, and is careless whether

they answer or not.

In general, however,

he remains quite silent during this first stage of the passage, as do also

the rowers, who either rest the paddles horizontally, or allow their circular

blades to float on the surface of the water.

Meanwhile the

boat rolls from side to side, or is heaved smartly upwards as the swell,

just on the eve of breaking, lifts her into the air, and ...

Page 114

... then drops

her again into the hollow with the most sea-sickening velocity.

I should state,

that during this wofully unpleasant interval, the masullah boat is placed

side-ways to the line of surf, parallel to the

shore, and, of

course, exactly in the trough of the sea.

I have often watched

with the closest attention to discover what were the technical indications

by which these experienced boatmen inferred that the true moment was arrived

when it was safe to enter the surf, but I could never make out enough to

be of much professional utility.

It was clear,

indeed, that the proper instant for making the grand push occurred when

one of the highest waves was about to break

— for the greater

the dash, the greater the lull after it.

But how these

fellows maanaged to discover, before-hand, that the wave, upon the back

of which they chose to ride in, was of that exact description, I could

never discover.

On the approach

of a swell which he knows will answer his purpose, the steersman, suddenly

changing his quiet and almost contemplative air for a look of intense anxiety,

grasps his oar with double firmness, and exerting his ...

Page 115

... utmost

strength of muscle, forces the boat's stern round, so that her head may

point to the shore.

At the same time

he urges his crew to exert themselves, partly by violent stampings with

his feet, partly by loud and vehement exhortations, and partly by a succession

of horrid yells, in which the sounds Yarry ! Yarry ! Yarry ! ! ! predominate

— indicating to the ears of a stranger the very reverse of self-confidence,

and filling the soul of a nervous passenger with infinite alarm.

These fearful

noises are loudly re-echoed, in notes of the most ominous import, by all

the other men, who strain themselves so vigorously at the oars, that the

boat, flying forwards, almost keeps way with the wave, on the back of which

it is the object of the steersman to keep her.

As she is swept

impetuously towards the bar, a person seated in the boat can distinctly

feel the sea under him gradually rising into

a sheer wave,

and lifting the boat up — and up — and up, in a manner exceedingly startling.

At length the

ridge, near the summit of which the boat is placed, begins to curl, and

its edge just breaks into a line of white fringe along the upper edge ...

Page 116

... of the perpendicular

face presented to the shore, towards which it is advancing, with vast rapidity.

The grand object

of the boatmen now appears to consist in maintaining their position not

on the very crown of the wave, but a little further to seaward, down the

slope, so as to ride upon its shoulders, as it were.

The importance

of this precaution becomes apparent, when the curling surge, no longer

able to maintain its elevation, is dashed furiously forwards, and dispersed

into an immense sheet of foam, broken by innumerable eddies and whirlpools

into a confused sea of irregular waves rushing tumultuously together, and

casting the spray high into the air by impinging one against the other.

This furious turmoil often whirls the masullah boat round and round, in

spite of the despairing outcries of the steersman, and the re-doubled exertions

of his screaming crew, half of whom back their oars, while the other half

tug away in vain endeavours to keep her head in the right direction.

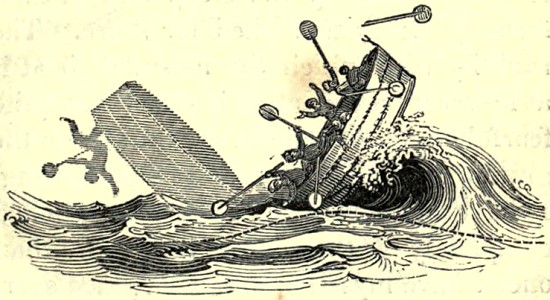

I have endeavoured to describe the correct and safe method of riding over the surf on the outer bar upon the back of a wave, a feat in all conscience sufficiently ...

Page 117

... ticklish ;

but wo betide the poor masullah boat which shall be a little too far in

advance of her proper place, so that, when the wave curls over and breaks,

she may be pitched head foremost over the brink of the watery precipice,

and strike her nose on the sand-bank.

Even then, if

there happen, by good luck, to be depth of water over the bar sufficient

to float her, she may still escape ; but should the sand be left bare,

or nearly so, as happens some-times, the boat is almost sure to strike,

if, instead of keeping on the back or shoulder of the wave, she incautiously

precedes it.

In that unhappy

case, she is instantly tumbled forwards, heels over head, while the crew

and passengers are sent sprawling

amongst the foam.

ILLUSTRATION

Note the dotted-line,

intended ti illustrate the depth of the shallow sand bank.

Page 118

Between the sharks

and the catamaran men a race then takes place — the one to save, the other

to destroy — the very Brahmas and Shivas of the surf!

It is right,

however, to mention, that these accidents are so very rare, that during

all the time I was in India I never witnessed one.

There is still

a second surf to pass, which breaks on the inner bar, about forty or fifty

yards nearer to the shore.

I forget, however,

exactly the method by which this is encountered.

All I recollect

is, that the boatmen try to cross it, and to approach so near the beach,

that, when the next wave breaks, they shall be so far a-head of it that

it may not dash into the boat and swamp her, and yet not so far out as

to prevent their profiting by its impulse to drive them up the steep face

of sand forming the long-wished for shore.

The rapidity

with which the masullah boat is at last cast on the beach is sometimes

quite fearful, and the moment she thumps on the ground, as the wave recedes,

most startling.

I have frequently

seen persons pitched completely off their seats, and more than once I have

myself been fairly turned over, ...

Page 119

... and with all

the party, like a parcel of fish cast out of a basket !

In general no

such untoward events take place, and the boat at length rests on the sand,

with her stern to the sea.

But as yet she

is

by no means far enough up the beach to enable the passengers to get out

with comfort or safety.

Before the next

wave breaks, the bow and sides of the boat have been seized by numbers

of the natives on the shore, who greatly assist the impulse when the wave

comes, both by keeping her in a straight course, and likewise by preventing

her upsetting. These last stages of the process are sometimes very disagreeable,

for every time the surf reaches the boat, it raises her up and lets her

fall again, plump on the ground, with a violent jerk.

When at last

she is high enough to remain beyond the wash of the surf, you either jump

out, or more frequently descend by means of a ladder, as you would get

off the top of a stage-coach ; and turning about, you look with astonishment

at what you have gone through, and thank Heaven you are safe !

The return passage from the shore to a ...

Page 120

... ship, in a

masiillah boat, is more tedious, but less dangerous than the process of

landing.

This difference

will easily be understood, when it is recollected that in one case the

boat is carried impetuously forward by the waves, and that all power of

retarding her progress on the part of the boatmen ceases after a particular

moment.

In going from

the shore, however, the boat is kept continually under management, and

the talents and experience of the steersman regulate the affair throughout.

He watches, just

inside the surf, till a smooth moment occurs, generally after a high sea

has broken, and then he endeavours, by great exertions, to avail himself

of the moment of comparative tranquillity which follows, to force his way

across the bar before another sea comes.

If he detects,

as he is supposed to have it always in his power to do, that another sea

is on the rise, which will, in all probability, curl up and break over

him before he can row over its crest and slide down its back, his duty

is, to order his men to back their oars with their utmost speed and strength.

This retrograde

...

Page 121

... movement withdraws

her from the blow, or, at all events, allows the wave to strike her with

diminished violence at the safest

point, and in

water of sufficient depth to prevent the boat taking the ground injuriously,

to the risk of her being turned topsy-turvy.

I have, in fact,

often been in these masullah boats when they have struck violently on the

bar, and have seen their flat and elastic bottoms bulge inwards in the

most alarming manner, but I never saw any of the planks break or the seams

open so as to admit the water.

It is very interesting

to watch the progress of those honest catamaran-fellows, who live almost

entirely in the surf, and who, independently of their chief purpose of

attending the masullah boats, are much employed as messengers to the ships

in the roads, even in the worst weather.

Strange as it

may seem, they contrive, in all seasons, to carry letters off quite dry,

though, in getting across the surf, they may be

overwhelmed by

the waves a dozen times.

I know of nothing

to be compared to their industry and perseverance, except the pertinacity

with which an ant carries a grain ...

Page 122

... of corn up a wall, though tumbled down again and again.

I remember one

day being sent with a note for the commanding officer of the flag-ship,

which Sir Samuel Hood was very desirous should be sent on board ; but as

the weather was too tempestuous to allow even a masullah boat to pass the

surf, I was obliged to give it to a catamaran-man.

The poor fellow

drew off his head a small skull-cap made apparently of some kind of skin,

or oil-cloth, or bladder, and having deposited his despatches there-in,

proceeded to execute his task.

We really thought,

at first, that our messenger must have been drowned even in crossing the

inner bar, for we well nigh lost sight of him in the hissing yeast of waves

in which he and his catamaran appeared only at intervals, tossing about

like a cork in a pot of boiling water.

But by far the

most difficult part of his task remained after he had reached the comparatively

smooth space between the two lines of surf, where we could observe him

paddling to and fro as if in search of an opening in the moving wall of

water raging ..

Page 123

... between him

and the roadstead.

In fact, he was

watching for a favourable moment, when, aftai; the dash of some

high wave, he might hope to make good his transit in safety.

After allowing

a great many seas to break before he attempted to cross the outer bar,

he at length seized the proper moment, and

turning his little

bark to seaward, paddled out as fast as he could .

Just as the gallant

fellow, however, reached the shallowest part of the bar, and we fancied

him safely across, a huge wave, which had risen with unusual quickness,

elevated its foaming crest right before him, curling upwards many feet

higher than his shoulders.

In a moment he

cast away his paddle, and leaping on his feet, he stood erect on his catamaran,

watching with a bold front the

advancing bank

of water.

He kept his position,

quite undaunted, till the steep face of the breaker came within a couple

of yards of him, and then leaping head foremost, he pierced the wave in

a horizontal direction with the agility and confidence of a dolphin.

We had scarcely

lost sight of his feet, as he shot through the heart ...

Page 124

... of the wave,

when such a dash took place as must have crushed him to pieces had he stuck

by his catamaran, which was

whisked, instantly

afterwards, by a kind of somerset, completely out of the water by its rebounding

off the sand bank.

On casting our

eyes beyond the surf, we felt much relieved by seeing our shipwrecked friend

merrily dancing on the waves at the

back of the surf,

leaping more than breast-high above the surface, and looking in all directions,

first for his paddle, and then for his catamaran.

Having recovered

his oar, he next swam, as he best could, through the broken surf, to his

raft, mounted it like a hero, and once more addressed himself to his task.

By this time,

as the current always runs fast along the shore, he had drifted several

hundred yards to the northward farther from his point.

At the second

attempt to penetrate the surf, he seemed to have made a small miscalculation,

for the sea broke so very nearly over him, before he had time to quit his

catamaran and dive into still water, that we thought he must certainly

have been drowned.

Not ...

Page 125

... a whit, however,

did he appear to have suffered, for we soon saw him again swinging to his

crude vessel.

Many times in

succession was he thus washed off and sent whirling towards the beach,

and as often obliged to dive head foremost through the waves.

But at last,

after very nearly an hour of incessant struggling, and the loss of more

than a mile of distance, he succeeded, for the first time, in reaching

the back of the surf, without having parted company either with his paddle

or with his catamaran.

After this it

became all plain sailing; he soon paddled off to the Roads, and placed

the admiral's letter in the first lieutenant's hands as dry as if it had

been borne in a despatch-box across the courtyard of the Admiralty, in

the careful custody of my worthy friend Mr. Nutland.

I remember, one

day, when on board the Minden, receiving a note from the shore by

a catamaran lad, whom I told to wait for an answer.

Upon this he

asked for a rope, with which, as soon as it was given him, he made his

little vessel fast, and lay down to sleep in the full blaze of a July sun.

One of his arms

and ...

Page 126

... one of his

feet hung in the water, though a dozen sharks had been seen cruising round

the ship.

A tacit contract,

indeed, appears to exist between the sharks and these people, for I never

saw, nor can I remember ever having heard of any injury done by one to

the other.

By the time my

answer was written, the sun had dried up the spray on the poor fellow's

body, leaving such a coating of salt, that he looked as if he had been

dusted with flour.

A few fanams

— a small copper coin — were all his charge, and three or four broken biscuits

in addition, sent him away the happiest of mortals.

It has sometimes

occurred to me, that professional men, both in the army and in the navy,

ought to study all the tactics of these masullah boats, and to make themselves

acquainted with the principle of their construction.

Of what infinite

importance to the army, for instance, might not fifty or a hundred of these

boats have proved, when our troops were landed, through the surf, at the

mouth of the Adour in 1814?

It is matter of considerable surprise to every one who has seen how well the ...

Page 127

... chain pier

at Brighton stands the worst weather, that no similar work has been devised

at Madras.

The water is

shallow, the surf does not extend very far from the beach, and there seems

really no reason why a chain pier should not be erected, which might answer

not only for the accommodation of passengers, but for the transit of goods

to and from the shore.

Before quitting

this subject, I think it may be useful to mention, that by far the best

representation of this celebrated surf which I have ever seen, is given

in the noble Panorama of Madras, painted by Mr. W. Daniell, and

exhibited last year.

I rejoice to

learn that this highly characteristic work will again be open to the public,

in a more accessible situation than that in which it formerly stood.

William Daniell:

Southwest

View of Fort St. George in 1820 (detail).

|

Fragments of Voyages and Travels. Third series, Volume 2,.. R. Cadell, Edinburgh,1832 Chapter III and Chapter IV. Internet Archive http://archive.org/details/fragmentsofvoyag02halluoft. |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |