As the pieces of plank which

they had detached from the inside of the boat were too

short, and were not sufficient to go quite round the

edge, they were obliged, when the sea ran very high, to

lie down several times along the gunwale on each side,

with their backs to the water, in order to prevent the

waves from entering the boat; and thus with their bodies

to repel the surf, whilst the other, with the Dutch hat,

was constantly employed in baling out the water; besides

which the boat continued to make water at the leak,

which they were unable to stop entirely.

It was in this melancholy

situation, and all of them quite naked, that they kept

the boat before the wind as well as they could.

The night of the first day after their shipwreck arrived

before they had well completed their sail; but although

it became quite dark, they contrived to keep the boat

running before the wind at the rate of about a league an

hour.

The second day was more calm; they each ate an onion, at

different times, and soon began to feel the effect of

thirst.

Towards night the wind became violent and variable,

sometimes blowing from the north, which caused them

great uneasiness, as they were then obliged to steer

south, in order to keep the boat before the wind, and

their only hope of being saved was on their proceeding

from east to west.

On the third day their

sufferings were excessive, as they had not only to

endure hunger and thirst, in themselves sufficiently

painful, but also the heat of the sun, which scorched

them in such a manner, that from the neck to the feet

their skin was as red and as full of blisters as if they

had been burned by a fire.

Smarting under this accumulation of bodily pain, the

captain seized the dog, and plunged the knife into his

throat.

They caught his blood in the hat, receiving in their

hands and drinking what ran over, and then drinking in

turn out of the hat, with which they felt themselves

very much refreshed.

The fourth day the wind was

extremely violent, and the sea very high, so that they

were more than once on the point of perishing: it was on

this day, in particular, that they were obliged to make

a rampart of their bodies to repel the waves.

About noon a ray of hope dawned upon them, but only to

experience bitter disappointment.

They perceived a sloop, commanded by Captain Southey, a

particular friend of Captain Aubin, which, like the

Betsey, belonged to the island of Barbadoes, and was

bound for Demerara; and this vessel came so near that

they could see the crew walking upon the deck, and

shouted to them: but unfortunately they were neither

seen nor heard.

Being obliged by the violence

Page 460

of the gale to keep the boat before the wind, for fear

of foundering, they had passed her a great

distance before she crossed them, the sloop steering

direct south, and they bearing away to the west.

This disappointment so discouraged the two seamen,

that they refused to make any more exertions to save

their lives; in spite of all that could

be said, one of them would do nothing, not even bale out the water which was

every minute gaining upon them.

In vain did the captain have recourse to entreaties, and,

falling on his knees, implore the assistance of the obdurate seaman; he remained unmoved; till at

length the captain and mate prevailed by threatening to

kill them instantly with the topmast, which

they used to steer by, and to kill themselves

afterwards, in order to put a period to their misery.

This menace seemed to make some impression on them,

and they resumed their occupation of baling as

before.

The captain this day set the others the example of eating a piece

of the dog with some onions : it was with great

difficulty that he swallowed a few mouthfuls, but in the course of an hour

afterwards he felt that this small morsel of food had given

them new vigour.

The mate, who was of a much stronger

constitution, ate more.

One of the men also tasted it; but the other, whose

name was Comings, absolutely refused to swallow a

morsel, protesting that he could not.

The fifth day was more calm, and the sea much smoother.

At day-break they perceived an enormous shark, full as

large as the boat, which followed them for several hours as

a prey that was evidently destined for him: they also

found in the boat a flying-fish, which had dropped there

during the night; this they divided into four parts,

which they chewed to moisten their mouths, and it

proved a very seasonable relief, though so little

inadequate to their necessities, that on this day,

when pressed with hunger and despair, the mate, Williams,

had the generosity to exhort his companions to cut off

a piece of his thigh, in order to refresh themselves with

the blood and support life.

The wind freshened during the night, and they

had several heavy showers, when they tried to get some

rain-water by wringing the trowsers which

served them for a sail, but when they caught it in

their mouths it proved to be as salt as that of the sea, the men's clothes having been so often soaked with

sea-water, that they, as well as the hat, were

impregnated with salt.

They had, therefore, no other resource, but to open

their mouths, and catch the drops of rain as they

fell upon their tongues to cool them: after the shower was over

they again fastened the trowsers to the mast.

On the sixth day the seamen,

notwithstanding all the remonstrances of the captain and mate, persisted in drinking sea-water, which purged them so excessively that they fell into a kind of delirium, and

were no longer of the slightest service in managing their frail

bark.

As for the others, they each kept a nail in their mouths,

and, from time to time, sprinkled their heads with

water to cool them; from these ablutions they found

their heads were more easy, and themselves generally

better.

They also tried several times to eat of the dog's flesh with a morsel of onion, and

thought themselves fortunate if they could get down

three or four mouthfuls.

On the seventh day the weather was

fine, with a moderate breeze, and the sea perfectly calm.

The two men who had drank sea-water grew so weak about noon that they began to

talk wildly, like those who are light-headed, not

knowing any longer whether they were at sea or on shore.

The captain and mate were also so weak that they

could hardly stand on their legs, or steer the boat in their

turns, much less bale the water from the boat, which now

made considerably at the leak.

On the morning of the eighth day, John Comings died, and about three

hours afterwards the other seaman,

George Simpson, also expired.

That same evening, just before the sun had

withdrawn his light, they had the inexpressible

satisfaction of discovering the high lands on the west point of the island of Tobago.

Hope inspired them with courage and infused new

strength into their limbs.

They kept the head of the boat towards the land all night,

with a light breeze and a strong current, which was in

their favour.

The captain and mate were that night in an

extraordinary situation; their two comrades lying dead

before them, with the land in light,

having very little wind, to approach it, and being

assisted only by the current which

drove strongly to westward.

In the morning, according to their own computation,

they were not more than five or six leagues

from the land, and that happy day was the last of their

sufferings at sea.

They kept steering the boat the whole day

towards the shore, though they were no longer able to

stand.

Towards evening the wind lulled,

and at night it was a perfect calm; but about two

o'clock in the morning the current cast

them on the beaches of Tobago, at the foot of a high shore

between Tobago and Man-of-War Bay, which is the easternmost

part of the island.

The boat soon bulged with the shock, and her

two fortunate occupants crawled to the shore, leaving

the bodies of their two

deceased comrades in the boat, and the remainder of the dog, which, by this time, had become quite

putrid.

They clambered, as well as

they could, on all-fours along the high coast,

which rose almost perpendicularly to the height of three or four hundred

feet.

A great number of leaves had

fallen on the place where they were, from the numerous trees

which grew over their heads, and these they collected

to lay down upon

Page 461

they waited for the coming

daylight.

As the dawn appeared they began to search for

water, and found some in the holes of the rocks, but it was brackish, and not fit to

drink.

They also found on the rocks several

kinds of shell-fish, some of which they

broke open with a stone, and chewed them to moisten

their mouths.

Between eight and nine

o'clock in the morning they were perceived by a young

Caraib, who was alternately swimming and walking

towards the boat.

As soon as he had reached it, he called his

companions with loud shouts, at the same time

making signs of the greatest compassion.

His comrades instantly followed him, and swam

towards the captain and mate, whom they had perceived

almost at the same time. The eldest of the party, a man apparently about sixty years of age,

approached them with the two youngest,

whom they afterwards learned were his son and

son-in-law.

At the sight of the poor sufferers, these compassionate men

burst into tears, while the captain

endeavoured, by words and signs, to make them

comprehend that he and his mate had been at sea for nine

days, in want of every thing.

The Caraibs understood a few

French words, and signified that they would fetch a

boat to convey them to their dwelling.

The old man then took a handkerchief from his

head, and tied round the captain's

head, and one of the young Caraibs gave Williams his straw hat; the other swam

round a projecting rock and brought them a calabash

of fresh water, some cakes of cassova, and

a piece of boiled fish; but they had been so long

without food that they were unable to eat any.

The two others took the corpses out of the boat and laid them upon the rock, after

which all three of them hauled the boat out of the water.

They then departed to fetch their canoe, leaving the poor

shipwrecked mariners with every mark of the utmost compassion.

About noon they returned

in their canoe, to the number of six, and

brought with them, in an earthern pot, something

resembling soup, which they thought to be delicious.

Of this they partook, but the captain's

stomach was so weak that he immediately cast it up

again.

In less than two hours they arrived at Man-of-War Bay, where the huts of the Caraibs were situate.

They had only one hammock, in which the hospitable

natives laid the captain,

while the women, who were in the hut, made

them a very agreeable mess of herbs and

broth of quatracas

and pigeons.

They also bathed his feet with a decoction of tobacco and

other plants, and every morning the man lifted

him out of the hammock and carried him in his arms beneath

a lemon tree, where he covered him with plantain

leaves to screen him from the sun.

There they anointed the bodies of the poor sufferers with a kind of oil, to cure

the blisters raised by the sun.

Their compassionate entertainers had even the generosity to give each of them a shirt

and a pair of trowsers, which they had procured from the ships that

came from time to time to trade with them for

turtles and tortoise-shell.

The method pursued by the natives in

healing the numerous wounds which had broken on the bodies of these

unfortunate mariners, was this: after they had

completely cleansed the wounds, they

kept the patient with his legs suspended in the air, and

anointed them morning and evening, with an oil

extracted from the tail of a small crab,

something resembling what the English call

the soldier-crab, because its shell is red and

which is obtained by bruising a quantity of the ends of their tails,

and putting them to digest upon the fire in a

large shell.

After thus anointing them they were covered with

plantain leaves till the wounds were

healed.

Thanks to the nourishing

food procured them by the Caraibs, and

the humane attention which was bestowed upon

them, the captain was able, in about three weeks time,

to support himself upon crutches, like a person

recovering from a very severe illness; but anxious

to return to his own friends, as early as possible,

he cut his name with a knife upon several boards,

and gave them to different Caraibs to show them to

any ships which might chance to approach the coast.

Still they almost despaired of seeing any

arrive, when a sloop from Oroonoko, laden with

mules, and bound for St. Pierre, in the island of Martinique,

touched at the sandy point on the west side of Tobago.

The Indians showed the crew a plank,

up on which was carved the name of Captain

Aubin, and acquainted them with the dreadful

situation of him and his companion, which those on board

the vessel related, when they arrived at St.

Pierre.

Several merchants with whom Captain Aubin was

acquainted, and who traded under Dutch colours,

happened to be there at the time, and

they transmitted the information

to the owners of the Betsey,

Messrs. Roscoe and Nyles, who instantly despatched a

small vessel in quest of the survivors, who, after living about nine

weeks with this benevolent and hospitable tribe of savages,

embarked and left them; their regret at doing so

being only equal to the joy and

surprize which they had experienced at meeting with

them.

As the vessel was

ready to depart, the natives

furnished them with an abundant supply of bananas,

figs, yams, fowls, fish, and fruits, particularly

oranges and lemons.

The captain had nothing to give them in return,

as an acknowledgment for their generous treatment,

but the boat, which they had repaired and used

occasionally for visiting their nests of turtles,

which, being larger than their canoes, was more

adapted to the purpose.

Of this he made them a present, and his friend,

Captain Young, who commanded the small

Page 462

vessel, assisted him to

remunerate his benefactors, by giving them all the rum he had

with him, which was about seven or eight

bottles.

He also gave them

several shirts and trowsers, some knives, fish-hooks

and sailcloth for the boat, with

needles and hooks.

At length, after two days

spent in preparations for their departure, they were

obliged to separate.

The Caraibs came down to the beach to the number of about thirty

men, women, and children, and all appeared to feel the deepest sorrow,

particularly the old man, who had acted as a father to them.

When the vessel left the bay, the tears flowed

from their eyes which still continued fixed upon their

departing friends, and they remained upon the beach, in a

line, until they lost sight of the vessel.

It was about cine o'clock

in the morning when the vessel sailed,

steering north-east, and in three days after they

arrived at Barbadoes, where they received, from the whole island,

marks of the most tender interest and the most generous

compassion; indeed, the benevolence of the inhabitants was unbounded.

The celebrated Dr. Hilery, the author of a treatise on the diseases

peculiar to the island, came to see them, accompanied by Dr.

Silihorn, and both prescribed various remedies, but

without effect.

Both of them were unable to speak but with the greatest

difficulty.

Williams remained at Barbadoes, but the captain, being

more affected and less robust, was advised, by the physicians, to

return to Europe.

In compliance with their advice he went to London,

where he was attended by some of the most celebrated physicians; and, after a

judicious treatment of about five

months, he was so far restored to a state of convalescence,

as to be enabled to resume his ordinary avocation.

Odile Gannier: In Search of Indian

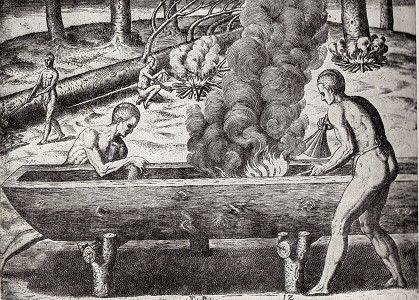

Navigators.

When Europeans Discovered the Caribbean area, they were

astonished by the extraordinary development of the art

of navigation

among the Indians there.

The concept - and the very term Itself - of "canoe"

and "Pirogue" cam from the Antilles.

These Indian canoes along were, skillfully dug-out logs.

Paddled by a crew, they moved incredibly fast.

The discoverers, themselves sailors,

described and the manner in which the canoes were

built and cared for.

Indians in the Caribbean basin, whether they were

Arawak or Carib, belonged to neighbouring peoples such

as the Tupinamba, astutely Improved these boats in

many ways, demonstrating a y considerable level of

technical expertise.

The crews were not only sturdy and skillful, They were

good pilots with knowledge of the islands and a

remarkable system for taking bearings.

The problem of obtaining fresh supplies was diminished by fishing,

and preserving food for transportation.

Social life centred around the Indians' interest in

navigation.

The explorer's accounts shed light on the island and coastal societies of the

Caribbean and of northern South America, a subject that has had limited study.