| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

surfresearch.com.au

surfboard shooting in australia,

1909-1940

|

|

(About)

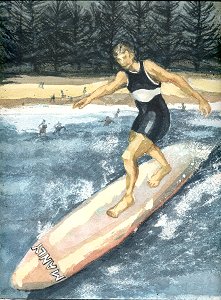

Right:

Tommy

Walker, Manly Beach, circa 1909.

|

|

Despite the

title,

this analysis is not confined to surfboard riding but, of

necessity, includes

the development of other wave riding craft on Australia’s

beaches in the

period.

Furthermore,

given

the domination of the surf life saving movement in the period,

the study

would be deficient not to account for this influence and the

interaction

of complementary and competing designs.

Specifically,

the

surfboat, the surf ski and the surfoplane are included along

with short

(prone) and long (ridden standing) surfboards.

Conversely, the

development of body surfing, or surf-shooting as it was

originally termed,

is only briefly mentioned.

While there is,

at least to this writer, an obvious connection between body

and board surfing

and developments in swimming technique at the turn of the 20th

century

(variously known as the Australian or American Crawl), this

appears to

have been completely overlooked by swimming historians.

Body surfing

skills

were a necessary pre-requisite for the confident use of any

type of surfcraft

and it was certainly Australian surfers’ success in

surf-shooting at the

turn of the century that encouraged their experimentation with

surfboards.

By the

mid-1970s,

the importance of body surfing skills was significantly

reduced with the

universal adoption of the leg rope (USA: surf leash).

Before

1900.

The earliest

surfboards

used in Australia were constructed from one solid piece of

timber.

The first

description

in an Australian publication is by Charles Steedman in 1867:

“A small deal (pine) board, about five feet long, one foot broad, and an inch thick, termed a ‘surf board,’ ”. (1)

This is a

substantial

board, similar to dimensions reported in Tahiti (2)

and Hawaii (3) in the

nineteenth century.

Despite

Steedman’s

identification of the craft as a "surf board”, the

text does not

clearly describe the technique of wave riding and there is no

indication

where he observed this practice.

This may merely

be a poorly transcribed account of any of the numerous

previously published

reports of Polynesian surfboard riding, and remains, at

present, an historical

anomaly.

In 2008,

Murray Walding

detailed a five foot six inch huon pine board, purchased on

Tasmania’s

east coast that “may well be oldest board in Australia”.

This is similar

to the dimensions prescribed by Steedman in 1867.

Claiming the

board

dates from the 1890s, the previous owner related that it “had

been copied

from Hawaiian boards brought to Tasmania by whalers”. (4)

From 1870 the

American

whaling industry was in rapid and terminal decline and in

"1880 the

Indian Ocean and Australian grounds were untroubled by

American whalers,

although the locals were still active.” (5)

While whaling

had

a long history in Tasmania, initially from shore bases before

moving to

offshore whaling ships, it was largely a spent force by the

1890s and the

last of the fleet, the Helen, was hulked about 1897. (6)

Certainly, prone boards similar to that identified by Walding

were in use

in Tasmania and Victoria by the 1920s, see below.

The possibility that visiting whalers were the first surfboard riders on the Australian coast is an interesting proposition given that whaling was practiced as early as1828 from bases at Cremorne and Mosman in Sydney. The demand for whale oil saw further bases operate from Eden of the south coast of NSW, Kangaroo Island and Victor Harbour in South Australia, Port Fairy in Victoria, and Port Lincoln in Western Australia.

The

willingness of

Polynesian islanders to enlist in the whaling industry is well

established,

the most famous, no doubt, Herman Melville’s fictional

Queequeg in Moby

Dick (1851).

Although the

novel

does not contain any reference to surfboard riding (Melville

did write

about it briefly in the earlier

Mardi and a Voyage Thither,1849),

after the destruction of the Pequod, the narrator is

saved by clinging

to Queequeg’s (prophetically constructed) coffin, in some

respects a hollow

surfboard, the similarity in template noted by John Dean

Caton, in 1878.

(7)

When a

longboat was

swamped in the surf when transferring stores on the Baja coast

in1857,

the ship's captain, Charles Scammon, reported:

“There were

several

Kanakas (Hawaiian islanders) among the crew, who immediately

saw the necessity

of saving the boat: and selecting pieces of plank to be used

as ‘surf-boards,’

put off through the rollers to rescue them.” (8)

This survival

technique

is not without precedent, the earliest use of a timber plank

as a rescue

device recorded by Homer in The Odyssey, circa 800 BC.

(9)

Later, the

account

was reprised by Luke's account of a ship wreck on the coast of

Malta in

The

Acts of the Apostles, when those who were unable

to swim were able

to survive with the assistance timber planks. (10)

While there is a probability that some Polynesian whalers traveled the world with their surfboards in the nineteenth century, determining a history of their activities is likely to be difficult and their impact on any local population conjecture. (11)

In 1910, Harold Baker, captain of the Maroubra Surf Life Saving Club, noted similar sized boards with a rounded nose and built from cedar rather than pine:

“The

surf-board

is used to a great advantage on flat, shallow beaches.

It is a

piece

of board, cedar for preference, about 18in. long, 10in.

wide, and about

half-an-inch in thickness.

It is square

at one end, and half-round at the other.

The rounded

end

is to the front when shooting.” (2)

Boards of this

type

progressively became introductory boards for, mostly, juvenile

surfriders.

At one of Duke

Kahanamoku’s

demonstrations at Freshwater Beach in 1915, in a photograph of

a large

crowd of onlookers, five youths carry boards of different

dimensions. (3)

Their role was

largely

supplanted with the introduction of the inflatable surf-mat in

the 1930’s.

There is

anecdotal

evidence that experienced Australian surf shooters began to

experiment

in the early 1900s with larger boards to replicate the widely

reported

skills of the famed surfriders of Polynesia, who rode upright.

They were

probably

inspired by a combination of written accounts, illustrations,

photographs,

and/or first person oral accounts from visitors to Hawaii.

Throughout the

nineteenth

century almost every account by Western tourists travelling to

the Hawaiian

Islands included some mention of surfboard riding. (4)

The most widely

published and effective was Jack London’s article “A Royal

Sport”

(1907) which recorded his introduction to surfboard riding,

encouraged

by Alexander Hume Ford and under the tuition of George Freeth.

(5)

Ford was

instrumental

in establishing the most influential of the early Hawaiian

surfriding clubs,

the Outrigger Canoe Club at Waikiki in 1907, paralleling the

formation

of the first surf life saving clubs in Australia.

On the strength

of London’s article, George Freeth was subsequently employed

to demonstrate

surfboard riding in California.

Initially, the

construction

of larger surfboards in Australia was probably based on

available drawings

or photographs of Polynesian surfboard riders.

Although the

earliest

illustrators struggled in depicting the fundamentals of

surfboard riding,

by the turn of the century most faithfully represented the

correct alignment

of board, rider and wave. (6)

The improvement

was probably assisted by the availability of photographic

images that correctly

demonstrated the complex dynamics.

The influence

of

photography is seen in a dramatic illustration of a female

surfboard rider

published in 1911 by Australian artist, Norman Lindsay. (7)

The

contribution

of still and motion photography to the ongoing development of

surfboard

design and surfriding performance should not be

under-estimated.

C. Bede Maxwell credits the champion swimmer, Alick Wickham, with shaping the first surfboard in Australia “from a length of driftwood picked up at Curl Curl.”(8)

Wickham was

not the

only Sydney surf shooter said to experiment with larger

surfboards.

At Freshwater,

circa

1905, “The Bell brothers, Frank and Charlie, spent crazy

hours on a

narrow outhouse door in the Freshwater surf” (9)

and several years later at Manly “Fred Notting painted a

brace of slabs

and named them Honolulu Queen and Fiji Flyer; gay they were

to look at

but they were not surfboards.” (10)

"The

Hawaiians

introduced us to this exhilarating, thrilling pastime, and

to these romantic

tropical islanders is due our warmest thanks.

But typical

of

our race, the youth of Australia has developed the art until

to-day they

are the equal In

skill of

their

dusky natatorial neighbours.

...

This

assertion

was verified during the 1915 visit to Australia of famous

Hawaiian swimmer

and surfboard expert, Duke Kahanamoku.

He enjoyed

our

surf, but despite his great knowledge of surfboard riding,

he admitted

that the young Australians excelled his own efforts under

the unusual local

conditions, of which, of course, he had little experience."

(1)

While Hay may

have

overstated the locals' skills, he is certainly qualified to

confirm that

Sydney boardriders were active before the arrival of

Kahanamoku in the

summer of 1914-1915.

He was one of

the

early (body) surf-shooters, a member of Manly LSC, a champion

member of

the Manly Swimming Club and competed in swimming races against

Duke Paoa

Kahanamoku and George Cunha during their Australian tour. (2)

Hay was

instructed

in the finer points of surfboard riding at by Duke at

Freshwater in January

1915 (3)

and later

wrote one of the earliest books on swimming and surfing

technique, discussed

below. (4)

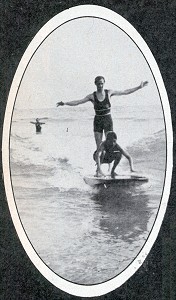

| Two

weeks after

Hay's article, The Referee quoted from a

letter under the heading

"Tommy

Walker Says- " I Brought First Surfboard To

Australia":

"I

saw an article

by you in 'The Referee' re surfboards, so

enclose a photo of myself

and surfboard taken in 1909 at Manly.

The

photograph is

reproduced, right.

The

sailing vessel

was the Poltalloch, a steel-hulled barque

built in Belfast in 1893.

(6) and the earliest

record of it visiting

Sydney is 13 June 1910, carrying a cargo of timber

from Portland, Oregon.

(7)

|

|

It is highly

probable

that this is the occasion recalled by Tommy Walker in his

letter to The

Referee.

The description

of the board as “Hawaiian” confirms the origin of the

board as imported

and the demonstration of considerable skill implies that

Walker had at

least one full season of riding experience.

An highly

interesting

report from Coffs Harbour is noted by Chris Conrick:

“Reports of

surfers

using planks of wood on which to ride waves were not unknown

at this time,

as

evidenced in

the following newspaper report in 1908:- ‘Board Riding Noted

on Town Beach

- Riders were

observed

using

10 feet lumps of wood to ride the waves and in this there

appeared an element

of danger.’ (9)

Since the

newspaper

does not name the riders, it is probable they were short-term

visitors

and not locals.

Conrick quotes

from

the Coffs Harbour Advocate, 22 January 1908, but the

original source

is yet to be confirmed.

A preliminary

search

of newspapers held by the Coffs Harbour City Library and the

State Library

of NSW indicates the Advocate was only published once

a week and

there is no actual edition for 22 January 1908.

If the report

has

any credibility (given the date may be incorrect), it raises

the possibility

that the riders may have been Hawaiian boardriders in the crew

of a visiting

ship.

Alternatively,

one

of the surfers may have been Tommy Walker, who is thought to

have worked

in the coastal shipping trade and is recorded as riding his

board further

north at Yamba circa 1912. (10)

The earliest

published

report appears to be by C. B. Maxwell in 1949:

"... in

1912,

C.D. Paterson, returned from a world tour with a 'real'

surfboard from

Hawaii; a solid, heavy redwood slab that no one could manage

in the rough

surf of North Steyne.

It was

handed

down to the other end of the beach where men like the Walker

Brothers,

Steve McKelvey, Jack Reynolds, Fred Notting and Basil Kirke,

all but turned

themselves inside out and upside down to master its

management." (2)

While Maxwell

extensively

researched her book on the Australian surf life saving from

unlimited access

to official records, this account was undoubtedly based on

anecdotal reports,

possibly from some of the participants.

Unfortunately

there

is no record of any relevant interviews in Maxwell's papers

held by the

Mitchell Library, Sydney. (3)

Reg Harris,

Manly

Life Saving Club historian, presented an expanded parallel

account, with

some major variations:

" Mr. C. D.

Paterson,

a foundation member of North Steyne Club and president of

the Surf Bathing

Association of N.S.W. (later the S.L.S.A. of Australia),

procured a board

from Hawaii.

North

Steyne club

members tried, without avail, to master the intricacies of

riding the heavy

board.

After they

had

suffered a lot of injuries and bruises, it was the general

opinion that

our surf was not suitable for board-riding.

The board came to be regarded as a lethal weapon, so it was taken to Mr. Paterson's home at The Spit, where it became the family ironing-board.

It had

excited

the interest of members at the south end of the beach,

however, and in

the 1912-13 season a number of Manly L.S. club members

decided to persevere

and master the art.

They

included

Jack Reynolds and Norman Roberts (both killed in World War

I), Geoff. Wyld,

Tom Walker (Seagulls), a 13-year-old boy named Claude West

... and an outstanding

woman surfer, Miss Esma Amor.

They used boards of a Gothic shape, made from Californian redwood, designed and constructed by North Steyne member Les Hinds, who was a local builder.

The boards

were

8 ft. long, 20 in. wide, 1 1/2 in. thick, and weighed 35

pounds.

They were

flat

on both sides, but had rounded edges to give a firm hand

grip." (4)

Note that of

the

various early boardriders reported by Maxwell and Harris; the

Walker Brothers, Jack Reynolds, Basil Kirke, Fred Notting,

Geoff Wyld,

Claude West, and Miss Esma Amor were all later identified as

proficient

board riders. (5)

Harris' report

that

Paterson's board ended up as a ironing board in the family

household has

become part of surfing folklore, however, given its probable

size and weight,

the proposition always stretched credulity.

In his

excellent

history of surfing movies published in 2000, Alby Thoms

reports that Paterson

brought the first known solid wood Hawaiian surfboard to

Australia on returning

from a world tour in 1909, significantly earlier than the date

suggested

by Maxwell and Harris. (6)

Thoms

essentially

reproduces the account of early surfboard riding in Sydney by

Maxwell (also

noting Wickham and the Bell brothers), however he does not

indicate a source

for the earlier date.

Newcastle SLSC

historian,

Chris Conrick, also suggests the date as 1909, based on

unidentified official

documents, with a slightly different scenario for the board's

acquisition:

“According

to

Surf Life Saving Assoc. records, the first Hawaiian

surfboard to find its

way to Australia was by

way of a

gift

to Mr. C.D. Paterson, the president of the association in

1909.” (7)

In 2007, Mark

Maddox

substantially reprised the story of Paterson's board in an

article published

in a history of the North Steyne Surf Life Saving Club (8).

Citing local

historian

Dr. Keith Amos, Maddox reports that Paterson was encouraged to

procure

a surfboard by "an American visitor" (9),

which he obtained on a visit to Hawaii, sometime before 1912.

He reproduces

an

unaccredited post-1914 newspaper cutting with the

recollections of an unidentified

North Steyne member and, the previously noted, Basil Kirke,

when at Manly

in 1911:

"one weekend

... C.D. Paterson brought back from Hawaii a surfboard,

first of its kind.

Basil Kirke,

Tommy Walker and Jack Reynolds launched the strange looking

object and,

after many spills, succeeded in riding it." (10)

Maddox then

notes

Tommy Walker's performance at the Freshwater carinival in

January 1912

(see above), although he implies Walker was a representative

of the North

Syene Club and not, as reported by the Daily Telegraph,

a member

of the short-lived Seagulls Club, one of four active at Manly

beach during

this period. (11)

The various

claims

for Paterson's acquisition of an Hawaiian surfboard between

1909 and 1912

appear to indicate significant inconsistencies with the

account of Tommy

Walker.

Clearly,

further

research, particularly in identifying relevant contemporary

documentation,

is required.

Despite deciding to ban surfboard use at Freshwater, complaints continued to be forwarded to Warringah and Manly Councils.(2)

In a Mid Pacific Magazine article published in January 1911, ostensibly promoting Australian ski fields, the current Director of the N.S.W. Govenment Tourist Bureau, Percy Hunter, noted:

Local government concerns for public safety, similar to those at Freshwater, also expressed at Cronulla (4) and further south, at Thirroul near Wollongong (5) indicate that experimentation with surfboards was in evidence on other metropolitan beaches.

This is further supported by various anecdotal

reports.

Dee Why SLC

historian,

E.J. Thomas notes:

“A Deewhy

identity

of the period (pre-1914), 'Long Harry' Taylor made a board

resembling an

old-fashioned church door, but his efforts in the surf were

so futile they

became ludicrous." (6)

There is a

similar

report from the North Coast at Newcastle:

“Joe Palmer

claims

that the first club member to use a surfboard on Newcastle

Beach was Cecil

Lamb, one of the staff of the Gentlemen's Club in Newcomen

Street, in the

1911-1912 season”. (7)

An account of

Duke

Kahanamoku's surfboard riding exhibition at Cronuulla in

February 1915

(see below) noted:

“While there

were already surfboard exponents on our own and other

metropolitan beaches,

Duke

Kahanamoku

first

focused public attention on surfboard riding in NSW.” (8)

In Queensland,

circa

1912, prone boards '' four to five feet long, one

inch thick and

about a foot wide

slabs of

cedar

or pine " were in use on Coolangatta Beaches. (9)

By March 1912

the

potential danger of surfboards to the general surf-bathing

public had come

to the attention of the NSW government and their use was

proscribed under

the local government act:

“10. Where

any

inspector considers that the practice of surf-shooting

(i.e., riding on

the crest of the

breaking

wave),

whether with or without a surf-board, is likely to endanger

or inconvenience

other

bathers,

such

inspector may order bathers to refrain from such practice or

to remove

to a place

where such

practice

will not cause danger or inconvenience.” (10)

While for many

commentators

it has been all too easy to date the beginnings of surfboard

riding in

Australia from the visit of Duke Kahanamoku in 1914-1915 (2),

the previous chapters demonstrate that this was not the case.

As is often

evident

in history, the story teller may have a vested interest in

securing a position

of prominance for a compatriot, a family member, their club,

their association,

or themselves.

For example

Manly

surfboard champion, Claude West, confidently proclaimed in

1939:

"I was the

first

Australian to take up surf-board rlding. ...

I Iearnt on

Duke

Kahanamoku's board, which he left here after introducing

surf-board riding

to Australia before the war." (3)

Kahanamoku was

not

the first Polynesian to profoundly effect Australian

surfriding.

Tommy Tana,

from

the island of Tanna in the New Herbrides first demonstrated

the rudiments

of surf shooting (body surfing) in the 1890s at South Steyne,

Manly.

Tana influenced

a group of Manly locals, one of whom, Fred Williams, became

the leading

exponent and an enthusiastic instructor. (4)

Polynesians

also

influenced the development of the crawl stroke in Australia,

notably Alick

Wickham. (5)

Following the

formation

of the surf life saving clubs in 1907, Pacific islanders

appeared at several

carnivals before 1914 in exhibitions of their surfing skills.(6)

Whereas in ancient Polynesia the surfriding elite were largely members of the royal class who, presumably, rode surfboards built by an artisan class of canoe builders (7) ; in the twentieth century, in a tradition associated with Duke Kahanamoku, elite riders were often at the forefront of board design and construction.

Upon arrival,

surf-oriented

members of the Swimming Association, notably Cecil Healy,

encouraged Duke

Kahanamoku to demonstrate his surfboard riding talents and

although he

had not brought a board, he indicated that one could be shaped

for any

upcoming demonstrations. (8)

Local

enthusiasm

saw a billet hastily prepared, which may have had the template

cut before

Duke, “proving himself a fine craftsman”, prepared the

rail and

bottom shape. (9)

This appears to

be suggested by Harris:

“A timber

firm,

George Hudson’s, donated a piece of sugar pine 9 ft long, 2

ft wide and

3" thick.

The firm did

the rough cutting to Duke’s instructions then he finished

off the finer

designing of the bottom of the board, to give it lift on a

wave.” (10)

After shaping,

the

board finished at 8 foot 8 inches long and 23 inches wide (11)

and made its first recorded appearance in the surf at

Freshwater on the

24th December 1914. (12)

In the

New

Year, further exhibitions were held on the 10th January at

Freshwater and

later that day at South Steyne on Manly Beach. (13)

There,

Kahanamoku

was joined by local surf-shooters, apparently keen to compare

their skills

with the visitor and in front of a considerable audience:

“The

breakers

were favorable for the pastime, and the Honolulu champion

made some magnificent

returns to the shore standing on his big surfboard. He

was however,

greatly impeded on this occasion by local surfers, who

wished to give exhibitions

of their own at the same time.” (14)

Further

surfboard

riding exhibitions were held in February at Deewhy (15)

and Cronulla. (16)

Given the

technology

of the day, presumably, after cutting the template with a hand

saw the

board was rough shaped with an adze and/or a draw knife and

then finished

with various grades of sandpaper. (17)

It is also to

be

expected that several coats of a natural oil and/or marine

varnish were

added to the board to prevent the timber from becoming

waterlogged.

Sugar pine was

not

the preferred timber for Hawaiian board building:

“The board

used

by Kahanamoku weighed 78lb, and was sugar pine. He would

have preferred

redwood, but a properly seasoned piece of that particular

timber, sufficiently

long, could not be procured in Sydney. The necessary shape

is almost that

of a coffin lid, with one end cut to very nearly a point.

The surf riding

board is thicker at the bottom than at the top, tapering all

the way.”(18)

In interviews

with

the press, Duke made it clear that light-weight was a critical

feature

that improved surfboard performance:

“Then too,

Kahanamoku

was at disadvantage with the board. It weighted almost

100lb, whereas the

board he uses as a rule weighs less than 25lb.” (19)

The board

appears

in several photographs taken during the tour and the template

is, compared

with all the other boards associated with Kahanamoku, unusual.

Specifically,

the

narrow nose template is uncharacteristic of most boards

produced after

the tour despite the reported influence of Kahanamoku’s

design:

“Sid

'Splinter'

Chapman (at Coolangatta, Queensland) could still recall the

dimensions

sixty years later ‘because the design that the Duke used was

the best.’

“(20)

The template

is certainly

different to the “surf shooting board” shaped by Oswald

Downing of Manly

in 1917, currently on display at the SLSA headquarters at

Bondi Beach.

Downing, a

trainee

architect, may have also been responsible for drawing up plans

for the

solid wood board printed and widely distributed by the Surf

Life Saving

Association of Australia. (21)

One reasonable

explanation

for this variation is that the template of the Freshwater

board was not

strictly Duke’s design, but was incorporated into this first

effort by

the tradesmen at Hudson’s.

While the

board has

immense historical significance, it is likely that other

boards subsequently

shaped in Australia by Duke were the real models upon which

local builders

based their designs.

Following

personal

instruction by Duke Kahanamoku in surfboard riding at

Freshwater, Fred

Williams and Harry Hay were reported to comment "well

we've already

ordered a board each … and we are going to master that game

beyond any

other." (22)

There is a

strong

implication that the boards are to be ordered directly from

Kahanamoku.

A report in the

Sydney

Morning Herald implies there were several boards built

during January

and may have included one shaped by Duke’s companion, George

Cunha, although

this is the only currently known reference to his association

with surfboard

riding during the tour:

“The

executive

had practically arranged another method of raising a sum for

patriotic

purposes for Friday 19th (February, 1915), at which the

Hawaiian party

were to be made the means of adding to the price of

admission by auctioning

several surf boards made by themselves.”

(23)

Presumably,

there

were vigorous attempts to secure seasoned redwood billets of

suitable dimensions

to build these later boards, one of which made its way to

Cronulla, the

property of ex-Manly surf-shooter, Ron “Prawn” Bowden. (24)

In 2008, a

possible

second board was unearthed, it’s owner suggesting Duke shaped

it in 1915

for a member of the well-established Horden family (25),

however at this point the board’s provenience awaits further

documentation.

(26)

Certainly the

total

number of surfboards on Sydney’s beaches was increasing:

“When one

Australian

had learned the art, others became interested and soon Tommy

Walker, Geoff

Wild (sic, Wyld), Steve Dowling, “Busty Walker, Billy Hill,

Lyle Pidcock

and Barton Ronald (sic, Ronald Barton?) began to

make boards similar

to the one Duke had made.” (27)

Kahanamoku’s

Freshwater

board was handed over to George and Monty Walker of Manly who,

“because

of the fine work Claude West had done in popularising

surfboard riding,

eventually gave it to Claude West, and he still has it, a

prized possession.”

(28)

Claude West, a

youth

of 16 at the time of Kahanamoku’s visit, became the leading

local surfboard

rider. Originally a member of Freshwater SLSC, he later moved

to the Manly

club.

He dominated

SLSA

surfboard events until 1924-1925, when West’s mantle as the

premier performer

passed on to another Manly club member, “Snowy” McAlister.

Claude West

donated

the board to the Freshwater SLSC in 1953.(29)

Kahanamoku’s

most

famous protégé was Freshwater teenager, Isabel Letham,

commonly

credited as Australia’s first female surfboard rider.

In January 1915

she accompanied Duke in a demonstration of tandem riding at

Freshwater

(30) before appearing

with him at

the Deewhy carnival on the 6th February. (31)

This was not

her

first pubic appearance at a Deewhy carnival, the previous

summer Letham

had competed in a woman’s surf race in front of a crowd of

several thousand.

(32)

In Sydney, his impact was immediate.

A report in

the Sydney

Sun

in January 1915 illustrated that the danger of surfboard

riding enthusiasts

to body surfers was not imaginary:

“Despite the

continual outcry against surf-boards, the dangerous aids to

shooters are

still being used, and one last night at Coogee hit Mrs.

Martha Green, aged

60, with such force that she is now in Prince Alfred

Hospital with her

right leg broken in two places.” (1)

One month after Duke's departure for further swimming and surfing demonstrations in New Zealand, the programme of the Surf Bathing Association of New South Wales' First Championship Carnival, at Bondi Beach on Saturday 20th March 1912, featured:

In Victoria,

official

regulation was apparently of minor concern to seventeen-year

old Grace

Wootton (nee Smith) who began riding at Point Lonsdale on a

borrowed prone

board, brought from Hawaii to Australia around 1915.

She became a

proficient

and enthusiastic surfrider and the following summer had her

own solid timber

board, approximately 6 ft x 16 inches wide, built for a cost

of 12 shillings

by a local carpenter. (3)

In Queensland, Charlie Faulkner read of Duke Kahanamoku's surfriding and used his experience (and board?) as an aqua planner on the Tweed River to ride at Greenmount in 1914-1915. (4)

Following the

Kahanamoku

tour, Isabel Letham became a noted surf-shooter and surfboard

rider, reported

to be “teaching board shooting”, and an “expert at

aquaplaning.”

(5)

In 1918, she

traveled

to America with hopes pursuing a career in the film industry.

(6)

After a brief

return

to Australia in 1921, Letham was appointed Director of

Swimming at the

San Francisco Women’s City Club until 1929 when, as a result

of a serious

injury, she returned to Sydney. (7)

With

Australia’s

ongoing commitment to the British war effort in Europe it may

be expected

that the enthusiasm for surfboard riding generated by Duke’s

demonstrations

would have been severely curtailed.

Surf life

saving

club members readily volunteered for service, severely

depleting the ranks

of many clubs during the war and several became inactive. (8)

A number of

serving

club members, such as Manly surf-shooter, Olympic swimmer and

journalist,

Cecil Healy, failed to return. (9)

However, with

no

general conscription, enlistment at twenty-one and limited

involvement

by women, surfboard riding continued to flourish on Sydney’s

beaches to

the extent that a weekly newspaper from Bondi, The Surf,

featured (body

and board) surf-shooting over the summer months of 1917-1918.

(10)

The third

edition

carried brief instructions for surfboard riding by Frank

Foran, then captain

of the North Bondi SLSC. (11)

Of the

fifty-one

surfboard riders identified by name, a significantly large

number were

female (eighteen, a ratio approximately 2:1).

“Busty” Walker

is

noted acquiring a new board at Manly, while at Bondi Arthur

Stone is said

to be building several and Reg Fletcher has painted his

surfboard white.

Ron Bowden is

reported

surf-shooting at both Manly and Cronulla, probably on his

board shaped

by Kahanamoku in 1915, noted above. (12)

Other surfboard

riders identified include several previously noted: Isabel

Letham, Fred

Notting, Geoff Wyld, Esma Amor, and Alick Wickham.

Across the

border

in Queensland, the Greenmount Surf Lifesaving Club procured

two copies

of Duke Kahanamoku's design, probably from Sydney.

The arrival of

the

boards prompted the construction of several replicas made and

ridden by

Sid 'Splinter' Chapman, Andy Gibson and a surfer known only as

Winders.

As in NSW, the

increased

use of surfboards raised issues of public safety and in 1916

Coolangatta

Town Council established restricted areas, infringements

punishable by

board confiscation. (13)

In 1919, Louis

Whyte,

a Geelong businessman who witnessed one of Duke Kahanamoku’s

exhibitions

at Freshwater, travelled to Hawaii with the intention of

learning the art.

He purchased

several

used redwood boards from Kahanamoku before returning to

Victoria where

he and Ian McGillivray rode them at Lorne.

One of the

boards

is held by the Surfworld Museum in Torquay, one is in the

hands of a private

collector and one was incorporated above the fireplace of the

Whyte family

beach house at Lorne. (14)

In the

mid-1920s,

Manly boardrider and lifesaver, Ainslie "Sprint" Walker, was

transferred

to his employer’s Melbourne office and initially surfed on his

board at

Portsea and Sorrento on the Mornington Peninsular.

As the son of

William

Walker, one of the pioneer surfriding family from Manly and

major figures

in the life saving movement, “Sprint” was a second-generation

Australian

surf-shooter.

He eventually

focused

on Torquay on the West Coast, the beach he considered best for

surfboard

riding, and was instrumental in the formation of the Torquay

SLSC.

After the

clubhouse

burnt down in 1970, destroying one of his early solid timber

boards, Walker

and “Snowy” McAlister built a replica from Canadian redwood

with an adze

in the traditional method. (15)

By the end of

the

decade, some riders applied a variety of decorative features

to their boards,

usually on the nose area of the deck.

Members of the

life

saving clubs added the logo of their club in paint, matching

the embroidered

badge on their swimming costume.

The rider’s

name

or initials were other popular additions and sometimes the

board was given

its own name, in the manner of Fred Notting’s Honolulu

Queen and

Fiji

Flyer, circa 1908, and noted above.

Very

occasionally,

the décor included an illustration such as a cartoon character

drawn

from popular culture. (6)

Usually

these décor features were painted on the board but in some

cases

simple text was carved into the timber.

While oiling

and

varnishing the timber remained the dominant method of

preserving the timber

from the salt water, some boards were fully coated with paint.

As in the case

of

Reg Fletcher at Bondi, the most popular colour was white (7)

and only rarely was a board multi-coloured. (8)

For timber

boards,

structural damage was promoted by the timber becoming

waterlogged and after

drying, cracking longitudinally along the grain.

Unlike hollow

timber

and the later fibreglassed boards, which tend to break across

the centre,

a severe collision could split a solid timber board in two

from nose to

tail.

This was

probably

a common problem with a tendency for Australian’s to ride

their boards

hard into the beach. In Hawaii, boards that had begun to split

longitudinally

were secured with a “butterfly wedge” that was inserted across

a crack.

(9)

Oswald

Downing’s

board shows a major split down the board that has been

repaired with a

simpler rectangular wedge near the nose.(10)

One solution

to the

problem used by Australian board builders was to shape and fix

a sheet

metal nose-guard, usually copper, attached with nails or

screws. (11)

By the

mid-1930s,

a more sophisticated method was the addition of the nose

plate, a bar of

stainless steel mitred into the timber about 12 inches (30 cm)

from the

tip of the nose and fixed with screws. (12)

This effective

structural

feature is unique to Australian boards of the period and does

not appear

on contemporary Hawaiian or Californian boards.

At Bronte,

Walter

V. H. Biddell designed the three-man Surf King in

1908, comprised

a timber frame, painted canvas and tin tubes, stuffed with

kapok.(2)

His next

design,

the Albatross circa 1910, was a more conventional

four-man surf

boat similar to the American dory.(3)

In 1908, Manly

SLSC

obtained their first surf boat, a double ended clinker built

with oars

Nos. 2 and 3 rowing side-by-side on the centre thwart.(4)

This was

followed

in 1913 by M.L.S.C., designed by Fred Notting, a Manly

SLSC member

and noted surfboard rider, which was commonly known as the

“Banana boat”

due to the accentuated rocker. (5)

Surfboat

sweeps,

often themselves surfboard riders (6),

were

noted for their wave riding bravado.

In the 1920s,

the

Holy Grail of big wave riding was the Queenscliff Bombora,

which broke

on extreme southerly swells, actually rolling in to

Freshwater.

The first

recorded

attempt to ride the break was in 1928 by the crew of North

Steyne’s Bluebottle

with Ratus Evans as sweep.

Although they

caught

a large wave, the boat was swamped in the whitewater and the

crew assisted

by Queenscliff SLSC members in their surfboat. (7)

The next

attempt,

in 1939, by the Manly LSC surfboat under Frank Davis had a

similar result,

this time assistance provide by the Freshwater boat with Don

Wauchope as

sweep oar.(8)

The Freshwater

Club,

in a boat nicknamed “Struggles” and captained by George

Henderson, would

be eventually credited with successfully riding several waves

at the Bombora

in 1948. (9)

In June 1961,

Sydney

newspapers featured front-page photographs of Freshwater

boardrider, Dave

Jackman, riding a large Queenscliff Bombora wave and claiming

it as a first.

Jackman himself

reported that several surfboard riders, including Claude West,

had preceded

him in the late 1930s, although he notes West was assisted out

to the break

by the Manly surf boat. (10)

Roger Duck and

Lou

Morath, a member of both the Balmoral Beach Club and Manly

SLSC, were also

credited with riding the Bombora on surfboards before

Jackman’s celebrated

rides of 1961.(11)

At Port

Macquarie,

on the mid-north coast of NSW, oyster farmer Harry McLaren

attempted to

shoot waves in a specialized canoe called a duck punt that was

propelled

with two small hand paddles, sometime between 1913 and 1920. (3)

The

unsuitability

of the flat-bottomed punt in the surf led him to build a new

craft with

pronounced rocker and a long based keel fin to facilitate wave

riding.

Critically, the

deck was enclosed with cedar panels with a draining bung,

thereby avoiding

the propensity for standard canoes to be swamped. It was to be

known as

the surf ski and was the first successful hollow timber

“board” built in

Australia.

In 1928,

visiting

Manly SLSC member and boardrider, Dr. J. S. 'Saxon'

Crakanthorp was intrigued

with McLaren and others riding at Town Beach on their skis.

No doubt aware

of

the difficulties encountered in the surf by standard canoes,

as ridden

by Notting, Walker and others, Crackenthrop was so impressed

he purchased

one.

On returning to

Manly, significantly enhanced the ski’s performance by fixing

two leather

foot straps and replacing McLaren’s small hand paddles with

the common

double-bladed canoe paddle.

The cedar

panels

were later replaced with marine plywood. In this improved

configuration,

Crackanthrop effectively claimed he was the inventor. (4)

In Australia,

the

knowledge “that for speed they must have less weight in

their boards

and more buoyancy” (4)

saw

some crude attempts to construct hollow boards in the period

up to

1930.

Similar to Tom

Blake’s

initial experiments, Claude West, circa 1918, attempted to

hollow out a

solid redwood board, but water easily penetrated cracks in the

timber and

the project abandoned. (5)

While Blake's

designs

would eventually dominate surfing across the Pacific into the

1950s, it

is unlikely his hollow construction was unique.

As noted above,

in Australia Harry McLaren's surfski was of similar

construction and photographic

evidence appears to indicate that hollow-type boards were used

in the the

world wide development of aquaplaning behind power boats.

Following

representation

to the SLSA authorities from the clubs where surfboard riding

was most

popular; Palm Beach, Collaroy, Manly and Cronulla; trials were

held in

the swimming pool of the Tattersals Club in Sydney in the

second half of

1931.

Perhaps the

death

at Collaroy of a local club member, George 'Jordie' Greenwell,

during a

belt and reel rescue attempt earlier that year tempered any

misgivings

of the examiners towards the surfboard and it was added to the

belt and

reel and the surf boat as official SLSA rescue equipment. (2)

Plans and

specifications

for building a solid redwood surfboard were added to the

eighth edition

of the SLSA Handbook issued for 1932.

There were also

instructions for its use and notes detailing rescue procedure

and rules

for a surfboard rescue event.

Two images of

surfboard

riders in action, one illustrating paddling technique and a

portrait shot

of several riders holding their boards were included in the

photographic

plates. (3)

Harry Hay, who

had

impeccable credentials in both sports, published Swimming

and Surfing

in

1931. (1)

A member of

Manly

SLSC, he was one of the early (body) surf-shooters and, as a

champion member

of the Manly Swimming Club, was conversant with the rapid

developments

in swimming technique that culminated in the universal

adoption of the

crawl as the dominant speed stroke.

In the summer

of

1914-1915, Hay played a major role in the tour of the Duke

Kahanamoku party.

He was

contestant

at the heats for the 100 yards swimming championship of NSW at

the Domain

carnival on 2nd January 1915, won by Duke Kahanamoku in world

record time.

(2)

In the surf, he

was one of the first locals to receive personal tuition in

surfboard riding

from Duke at Freshwater. (3)

Written in a

concise

and informative manner, Hay provides an excellent introduction

to riding

a solid timber board.

The chapter on

surfboard

riding in Surf- All About It (4),

also published in 1931, is less expert.

A substantial

book

of fifty pages, with extensive quality illustrations, it lacks

accreditation

of author, artist or publisher.

The author,

while

probably an experienced journalist, appears to have based his

account largely

on knowledge imparted by others and not extensive personal

surfing experience.

For example,

the

following could be said to be an optimistic view:

“It is no

harder

for a moderately skilful surfer to learn the use of the

board than it was

for him to learn the art of shooting.

And the risk

of danger is certainly no more.” (5)

H. Phillips' Surfing

Beaches

of Sydney, N.S.W. (6),

circa

1931, is a collection of professional beachside photographs

with

basic captions, whereas the other contemporary works use

illustrations

only.

The vast

majority

are at Manly or the beaches of the Eastern surburbs and

include beachcscapes,

female fashions, surf carnival march pasts and reel and rescue

competition.

There are

half-a-dozen

photographs of surfboats, several of canoes, and a number of

inflated craft.

The four images

of surfboard riders in action include one rider standing on

his head and

a female riding prone.

A photograph of

seven riders, of various ages and one female, holding their

boards illustrates

a range of board design and decor and, given the variation in

swimming

costumes, possibly representing several surf life saving clubs

at a competition.

Dr Ernest

Smithers

of Bronte, a Sydney doctor, developed the Surfoplane in the

years leading

up to 1932. (3)

It is unclear

how

Smithers came to his design, but in Europe experiments with

inflated watercraft

had been in progress for over sixty years, as reported by

Charles Steedman

in 1867, sometimes disastrously:

“not long

since,

in Paris, the inventor of a patent air-mattress was actually

drowned, together

with his assistant, through the mismanagement in some way of

a specimen

of his artificial life-preserving apparatus which he was

exhibiting in

public.” (4)

There are

competing

claims for the inventor of the surfoplane, (5)

for example SLSA historian Sean Brawley credits Bondi’s Stan

McDonald.

Examining the

events

of Black Sunday, the most celebrated rescue in the history of

Australian

surf life saving on 6th February 1938, Brawley comments:

"The

surfoplane

had been introduced to Bondi Beach a few seasons earlier by

Stan McDonald.

On his

retirement,

McDonald had designed a rubber surf mat that he called a

'beacher'.

Along with

his

chairs and mutton oil tan spray, McDonald leased the mats in

their hundreds;

riding them became a popular surfing activity at a time when

board riding

was still a marginal and almost exclusively a surf club

activity.

The surf

mats

soon became more popularly known as 'surfo- planes', the

name of a rival

surf mat manufacturer." (6)

Brawley’s best

approximate

date for McDonald’s introduction is circa 1934 (“a few” = 4 of

less?),

certainly post dating E. E. Smithers’ and C. D. Richardson's

patent application

for a "rubber surfboard” on 7th October 1932. (7)

The next summer

the Patent Office accepted a trademark design from Smithers

and Richardson

for the "Surfo-plane" (8)

and, by the mid-1930s, the company promoted them as hire items

in advertisements.

(9)

Surfing film historian, Albie Thoms notes the surfoplane ''was soon in mass production, being hired by the half hour on Sydney beaches, and proving popular with all ages and both genders. Surf-o-planes were... filmed for Movietone News 6/7 (1935), ... Movietone News 7/15 (1936), ... Movietone News 8/13 (1937), ... Movietone News 9/14 (1938), which included shots of Dr Smithers riding his invention at Bronte, ...and ... Movietone News 10/6 (1939)." (10)

Concerns about

the

potential danger of surfoplane riders to led to calls for them

to be segregated

from bodysurfers, but an inqury by a SLSAA sub-committee

in 1936

found no evidence for such drastic action. (11)

Around this

time,

surfoplane racing was included in some SLSAA carnivals, often

dominated

by Cronulla's Bob Holcombe who had nine consecutive wins

including the

1938 Australian Championship. (12)

The craft were

extremely

popular with Manly Life Saving Club reporting 261 rescues in

the 1938-9

season, half of which were carried out on or swept off rubber

floats. (13)

In 1955

surfoplane

plans and photographs were included in the Gear and Equipment

Handbook.

(14)

Although the

surfoplane

was used worldwide, including a report that included it in

events at the

Makaha Surfing Contest in the later 1930s (15),

the exact process and chronology of this distribution is

unclear.

In the United

States,

surfoplanes, “also called ‘surf rafts’ or ‘floats’- were

being used

in Virginia Beach, Virginia in the early ‘40s and in

Southern California

by the late ‘40s.” (16)

By the late 1960s its status in Australia as the dominant juvenile craft was under threat by the Coolite, a soft lightweight polystyrene board and by the mid-1970s, the rubber surfoplane had been largely replaced by an updated design, the inflatable canvas surf mat.

The same year,

Tom

Blake added a long base keel fin to his hollow board design, a

feature

that had already appeared in Australia on McLaren’s surf ski

circa 1928.

At the same

time

Blake also added a circular shaped stainless steel “big surf

handle” mounted

on the tail of the board, as an aid to controlling the board

from the tail.

(3)

Blake’s fin

did not

appear in any of the published plans of the his paddleboard

from 1933 to

1946 (4), but a two inch keel fin

with a 14

inch base was included as “a necessity” on a 11 foot Square

Tail Hollow

Riding Surf Board, dated 1937. (5)

The stainless

steel

tail handle, originally fitted to Blake’s Kalahuewehe

hollow board,

appears not have to been widely adopted by Hawaiian or

Californian hollow

board riders, based on a large number of photographs of the

period.

In Australia,

however,

“a gip handle at stern as safety measure” was specified

by the SLSA

in their Handbook of 1947 as a necessary addition to hollow

paddleboards.

(6)

It is unknown

if

the published plans for the laminated surfboard had any impact

on Australian

builders, but one report indicates Bern Gandy acquired an

imported board,

probably from California, and surfed it at Lorne in 1935-1936.

Gandy

subsequently

built a 10ft 6'' replica and took this board with him to

Sydney in 1938.

(4)

A board of

similar

construction to the laminated design, said to be from a

Geelong family

but its providence otherwise unclear, is held by a private

collector. (5)

|

A Photographic Anomaly: Ongoing research has yet to confirm the provenance of a photograph of tandem riders, reproduced right, that potentially calls into question the current understanding of the development of the hollow board in Australia, This

copy was printed

in a collection of black and white photographs under

the tittle "The

Old Timer's Album" in Surfer in 1965. (5)

Given

the board's

obvious extreme thickness, it is highly probable that

it could have only

been hollow.

|

|

Two distinct

designs

of surf ski began to emerge, the wide body model used for wave

riding and

an elongated ski to improve paddling performance for racing,

first developed

by Jack Toyer of Cronulla in 1936. (2)

Concurrently, at Maroubra 'Mickey' Morris and 'Billy' Langford

introduced

the double ski, although their first model proved too narrow.

(3)

The broad-beam

model,

like a surfboard, was ridden in a standing position when on

the wave with

the addition of a leash connecting the paddle to the nose,

probably to

keep the two apparatus together in the case of a wipeout,

which was more

probable when riding while standing.

One,

unaccredited,

photograph of several broad- beamed models was included in the

SLSA Handbook

of 1938. (4)

These skis were

first seen on film in Movietone News 8/51 in 1937 at Manly,

the riders

both sitting and standing. (5)

After

extensive testing

at Maroubra, the surf ski was adopted as standard life saving

equipment

in 1937 (6) and

included in

the Australian Championships as a rescue event with a paddler

and patient.

(7)

The skis proved

very popular and it was suggested that "the new craze is

giving the

surf board some very keen opposition." (8)

The same year,

Surf

Ski Manufacturers at Smith's Avenue, Hurstville marketed "the

new Ultra-Modern

Surf Ski" at seven pounds and fifteen shillings

including delivery

by rail or boat plus packing at two shillings and sixpence, or

fifteen

shillings deposit and payments of three shillings and sixpence

per week.

(9)

At the end of

the1930s

the surf ski made its first excursion outside Australian

waters:

“The Walker

Brothers

sent a surf ski to Duke Kahanamoku at Honolulu and members

of the Australian

Pacific Games Team which visited Honolulu in 1939 say Duke

was often seen

paddling around on his ‘ski from Australia’.” (10)

Despite

official

sanction, skis were not included in the SLSA Handbook of 1938,

except for

the photograph noted above, and in December, these skis

competed with canoes

in an SLSC carnival. (11)

The SLSA

Handbook

was later adjusted to include notes on Rescue Methods and

Rules for Control

by Clubs for surfboards and surf skis (12)

and eventually plans were included for an 18 feet single and a

22 feet

double ski. (13)

This was

specifically

a wave riding board and not competitive in paddling races.

Lou Morath used

a hollow plywood board for the surfboard trails, held on

Narrabeen Lakes,

to determine representatives to the upcoming Pacific Games.

The board was

approximately

11 feet long and unusually wide with a large square nose and

smaller tail

both sheathed in thin metal plates.

Typical of

Morath’s

exceptional craftsmanship, the deck has several contrasting

decorative

“vee” panels down the board.

Contemporary

photographs

of the trials illustrate two other boards similar in size and

shape, one

held by fellow Manly LSC member, Harry Wicke.

He was a noted

board

rider who, it has been inferred, was not considered for

selection due to

his German heritage, in a flurry of nationalist paranoia with

the outbreak

of war in Europe. (3)

Wicke’s board,

also

with metal nose and tail sheathing, is about 10 feet long.

Built by Palm

Beach

SLSC member Keightly 'Blue' Russell, the board is currently in

the Manly

LSC’s Australian Surfing Museum collection. (4)

Importantly,

these

three boards are not characteristic of the standard Tom Blake

hollow board

template and appear to be rather an attempt to produce a

lighter board

similar in dimensions to the earlier solid wood.

This perhaps

demonstrates

an independent Australian design influence, the most likely

candidate Harry

McLaren’s surf ski, as appropriated at Manly by Dr.

Crackanthorp.

‘Blue’

Russell, credited

with “starting the kneeling paddle fashion in Sydney”

(5),

was himself a competitor in the trials and subsequently a

representative

to Hawaii.

His personal

board,

and several others, in the trial photographs are substantially

longer than

the three detailed above, probably in excess of 14 feet.

Held nose down

by

their riders, their tails are cropped out by the top of the

image.

These models

appear

similar to the square nose and pin tail template to the Blake

design.

Following the

trails

Lou Morath (Manly), Keightly ('Blue') Russell (Palm Beach) and

Dick Chapple

(North Bondi) were selected as boardriding representatives in

a large Australian

team which attended the Pacific Games in Hawaii. (6)

As well

as

his solid wood wave riding board, Lou Morath probably took a

hollow board

to Hawaii different to the one he used in the trials.

A photograph,

titled

“Lou Morath and another paddler in training for the 1939

Pacific Games

" (7), shows him paddling a

board that

closely resembles one held by the Manly Art Gallery and Museum

(8)

with the number “2” and “Lou Morath” hand

painted in gold

script on the deck.

This 14 feet

long

board has contrasting wood paneling of the deck, somewhat

similar to the

board used at the trials, and long based solid timber keel

fin.

It’s pin nose

and

square tail are at variance with the standard Blake hollow.

The other

paddler,

on a board that bears the rescue reel logo used by several

Australian surf

life saving clubs, is possibly an Hawaiian competitor, perhaps

even Duke

Kahanamoku himself. (9)

Focused on

surfboard

competition, the Daily Telegraph detailed a brief

format:

"Events

proposed

are surf board out-and-home paddle race, surf board tandem

race, surf board

display, and

surfboard rescue race." (2)

From the first, the intention was have an Hawaiian team to

compete in

Australia the following year (perhaps to initiate an annual series

of competitions):

"A conditlon of the tour is that the Hawaiian Association

reciprocate

with a visit to Australia in 1940." (3)

Australian

surf lifesaving

officials were enthusiastic about the tour as an opportunity

to promote

their life saving methods in an international context.

The Surf Life

Saving

Association chairman, Mr. Adrian Curlewis, commented:

"I feel that

while taking part in the surf board championships our

represenatives should

give demonstrations of surf rescue work." (4)

Another

official

expressed confidence in the ability of the Australian

boardriders to provide

a vigorous contest:

"Mr. Hunter

said

tests had shown Australian surfers the equal to those in

other parts of

the world.

'The world

record

for a still water swim with a surf board is 31 1/2 sec.,'

said Mr. Hunter.

'I know of

several

who got within a few seconds of this time without special

training.' "

(5)

The current

record

holder was probably American, Tom Blake over a distance of 100

yards. (6)

" 'Paddling

record

times in the still water of a Honolulu canal, over a

distance from 100

yards to a mile,

are held by

Tom

Blake, an American.' said Mr. Russell yesterday."

Daily

Telegraph,

Friday, 10 February 1939, page 7

While the

format

of the competition had yet to be specified, most Sydney

boardriders thought

the surf at Waikiki was considerably less testing than their

own beaches,

a factor that would prove to be to their representatives'

advantage.

"Snow"

McAlister

noted:

"The broken

surf

of Australia demand tremendous skill of the surf-board

rider.

I think our

best

men have enough skill to match anybody in the surf."

(6) Daily

Telegraph

Wednesday, 8 February 1939. Page 1

A similar view

was

expressed by CIaude West:

"The type of

surf we have is the toughest in the world to master, and

Australians could

hold their own in the easier Honolulu surf.

...

The smooth,

unbroken

roller of Honolulu would be a picnic for our men. " (7)

Daily Telegraph

Thursday, 9 February 1939. Page 7

Harry Hay

expressed

similar view in an article, with the less than subtle title, "Australians

Are

'Tops' in Surfboard Riding":

"Our waves

are

irregular, bank up to great heights, and break some distance

from the shore.

In order to

choose

the correct type of wave and ride it expertly and safely,

one must summon

far greater daring and skill than the Waikiki rider has to

do." (8)

The Referee

Thursday,

9 February 1939. Page 15

John Ralston,

the

fomer president of Palm Beach Surf Life-Saving Club and who

apparently

had surfed at Waikiki (9), was far more circumspect in his

assessment:

SLSAA: Surf in

Australia,

November 1, 1936, pages 9-10.

"A feature

of

the board riding in Hawaii, which strikes the Australian

expert on first

experiencing the

sport there,

is the amazing angle at which the riders come across the

wave..."

"Nobody in

the

world could beat the Hawaiian beach boys in the surf."

However, it is

important

to note that the question of surfboard design was crucial,

Ralston also

noted:

"But with

fast,

hollow boards, and training, our men could compete with

anyone over there."

(10)

Daily

Telegraph

Wednesday, 8 February 1939. Page 1.

While the skills of Sydney's boardriders were being lauded in the press, "Blue" Russell, also of Palm Beach, was beginning to make serious practical tests against the stop watch on the flat water of Pittwater.

"In the

Pittwater

tests, a light hollow board of special three ply, about 15

feet 4ins. long

was used.

The board

was

built by Mr. Russell , who considers it as fast as boards

used at Honolulu.

It weighs

about

30lb., whereas a solid board would weigh about 60lb."

(11)

Daily Telegraph

Friday, 10 February 1939, page 7

Note Russell's

use

of "a light hollow board", possibly of his own design.

Before the end

of

February the range of program activities had expanded

considerably:

"They will

compete

against each other in the water, on surf-boards, in

Australian surf-boats,

in Hawaiian canoes, and the Australians will demonstrate the

surf rescue

system evolved here."

Daily Telegraph

Wednesday, 22 February 1939, page 1

Selection on

the

team to visit Hawaii was considered highly prestigous, and the

enthusiasm

was evident in a preview of that year's Australian

Championships:

"Almost

overshadowing

the championship carnival in current interest is the

proposed visit of

swimmers, surf board riders and a boat crew to Honolulu in

July." (2)

At the

Championships

at Manly Beach on18th March, the Surf Board Race was won by G.

Connor from

Bondi, second R. Russell of Palm Beach and third was J. Mayes

from North

Bondi (2).

However, for

unknown

reasons, these results were not considered sufficient to

finalise team

selection and further trials were held on Narrabeen Lakes, see

below.

Meanwhile,

various

clubs were vocal in support of their champions for inclusion

in the touring

party:

"Bob

Holcombe,

widely skilled surf competitor and current surfoplane

champion of

the Cronulla club, has nominated for the S.L.S.A. surf team

which will

tour Honolulu in June."

Volume 3 Number

8 April 1, 1939, page 14.

and

"All members

are confident that (Newcastle) Club Champion Alan

Fidler will secure

a berth on the Honolulu trip."

Volume 3 Number

9, May 1, 1939, page 8.

During April,

trials

were conducted on Narrabeen Lakes to determine selection for

the surfboard

paddlers to compete in Hawaii.

Some

competitors

included A. Major and R.K. Russell (Palm Beach), H.H.

Wicke, R. Duck,

F.C. Davis, L. Morath,

and R.

Lumsdaine

(Manly).

The boards, "

the latest types of hollow surfboards", were of

dirverse design

and lengths.

Volume 3 Number

9. May 1, 1939, page 7.

Eventually

Chapple

(North Bondi), Lou Morath (Manly-Balmoral) and Blue Russell

(Palm Beach)

were selected as the surfboard representatives.

By the end of

April

1939 a detailed programme had been prepared by the Hawaiian

Committee and

forwarded to the Surf life Saving Association of Australia.

Beginning with

their

arrival on 5th July, this consisted of official receptions,

parades, social

outings, two nights of swimming and diving events at the

Waikiki Natorium

and a third at Punahou Tank. .

The first night

at the Natorium was to include the100 Yards Surfboard Race for

Men, Open.

Sunday, July

16,

was to feature "Lifeboat, canoe, surf board, ski and

outboard motor

regatta at Ala Moana Canal in front of Ala Moana Park"

Some of these

proposed

events were:

"4. Hawaiian

surf board race, 1 mile (board must be 12 ft., at least 60

lbs., 12 inches

width at stern).

8.

Australian

ski paddling race- 1 mile- Hawaii v. Australia.

9. Surf

board

relay-women (8 to team)-1 mile straight course.

11.

Australian

lifeboat race- Hawaii v. Australia.

13. Surf

board

relay (8 men to team)- 1 mile straight course."

The final day

of

competition, Saturday 22 July, was to include:

"1.

Life-Saving

Rescue Race- Australia v. Hawaii.

2.

Australian

Lifeboat Race through Surf.

3. 100 Yards

Footrace on Sand Beach.

4. Surf

Board

Race through Surf.

5. 400 Yards

Relay Race on Sand Beach."

- Volume 3

Number

9. May 1, 1939, page 1.

The possible

incompatibility

of the reel and belt and the coral reefs at Waikiki was

foreshadowed:

"They say

the

R. and R. team for Hawaii is to be provided with military

boots to race

over the coral sea beds."

Volume 3 Number

10. June 1, 1939, page 14.

The boat crew

was

Frank B. Fraund (Palm Beach), Frank Davis (Manly) and Dickson,

Harkness

and Mackney (all Mona Vale).

The R. & R.

squad was Les McCay, (North Cronulla), Alan Fitzgerald, (North

Wollongong),

Hermie Doerner, (Bondi), Hec Scott, (Newcastle), Bill Furrey

(North Steyne)

and Alan Imrie (Burleigh Heads).

Doerne was a

noted

water polo player and team captain.

Robin Biddup

(Manly)

was probably selected as the strongest swimmer available, a

state champion

and winner of bronze medals for the 440 yards freestyle and as

a member

of the 220 yard freestyle relay (?) at the 1938 British Empire

Games in

Sydney.

As previously

noted,

the boardriders were Chapple, Morath and Russell.

Predominantly

from

the Sydney Clubs, the team included, perhaps diplomatically,

one representative

each from Newcastle, Wollongong and Burleigh Heads,

Queensland.

There were

seven

officials or supporters, Jack Cameron, H. Spry, H. Chapple,

Clem Morath,

Jack McMaster, Tom Meagher, F. Boorman, and Harry Hay. (2)

Hay first

competed

against the competition’s host, Duke Kahanamoku, now the

Sheriff of Honolulu,

at Stockholm in 1912 and an active participant in the

Hawaiian’s surfboard

riding demonstrations in Sydney in 1915.

P. Wynter

represented

Sydney’s Daily Telegraph. (3)

Albie Thoms

notes

the team was filmed at training for:

“Movietone

News

10/15 (1939) and Cinesound Review 397 (1939), and again on

their departure

for Movietone News 10/28 (1939) and Cinesound Review

400 (1939).

However

there

was no footage of their arrival...or of the paddling race".

(4)

Surf in

Australia

reported:

"Harold

Spry,

well-known Manly identity and ex-member of the Queenscliff

club, will be

visiting Hawaii

at the same

time

as the surf team.

Harold is an

expert amateur movie photographer, and we hope he will be

afforded all

facilities to

record the

team's

activities in film."

Volume 3 Number

10. June 1, 1939, page 14.

The existence

of

any footage taken in Hawaii by Harold Spry is currently

unknown.

Before the team departed, two surfboats were shipped to Honolulu

to

allow the Hawaiians time to familiarize themselves with the craft.

The other equipment, surfboards and the reel, probably travelled

with

the team.

There is possibility that surfskis were also taken, there was

already

one at Waikiki in the possession of Duke Kahanamoku (x), and maybe

some

surfoplanes.

In the preparations for a tour to New Zealand in 1937, it was

reported:

"Surfoplanes Ltd. are loaning a plane to each member and the

Bondi

Club are loaning a reel."

Surf in

Australia

February

1, 1937, page 11.

The team departed Sydney on the 23rd June in the s.s. Monterey and arrived in Honolulu on 5 July 1939.

On arrival

off

Diamond Head on Wednesday, 5th July, we were first met by

the two Australian

surf

boats,

manned

by Hawaiians and Americans.

Then came

Duke

Kahanamoku in a Customs cutter, accompanied by John

Williams, Secretary

of the

Executive

Committee,

and Don Watson, Committeeman.

Extracts from

Captain's

Report of Pacific Surf Games, October 3, 1939, page 2.

On Thursday

6th July:

The team had

the pleasure of being made honorary members of the famous

Outrigger Canoe

Club.

Water

conditions

were pleasant, because water temperatures here range from 66

degrees to

82, and

the weather

is

never colder than 56 nor warmer than 88.

Extracts from

Captain's

Report of Pacific Surf Games, October 3, 1939, page 3.

Sunday, 9th

July.-The

team made its first public appearance at 3 p.m. at Makapun,

giving

demonstration

of

R. and R. with details, followed by exhibitions of belt and

surf racing,

surf board

riding and

surf

boat work.

This

exhibition

amazed a crowd of 15,000 with the precision of the R. and R.

drill, and

much

favourable

comment

was heard on all sides.

Later, when

the

boat cracked a wave, the crowd went wild with excitement and

kept asking

the crew to give further exhibitions, which they did, and

were roundly

applauded by thousands lining the highway to Makapun.

Extracts from

Captain's

Report of Pacific Surf Games, October 3, 1939, page 3.

In front of

5,000

spectators at the swimming carnival at the Waikiki Natatorium

on Wednesday,

12th July:

"Robin

Biddulph

swam third in the 800 metres race, won by Nakama in Hawaiian

record time,

and in the

only other

event

we contested, the 400 metres relay, our team, consisting of

McKay, Doerner,

Fitzgerald

and

Furey, was successful.

In the heats

of the 100 yards board race Morath and Chapple qualified for

the final

by getting 1st and

3rd

respectively

in the 1st heat and Russell qualified in the second heat,

gaining 3rd place."

Extracts from

Captain's

Report of Pacific Surf Games, October 3, 1939, page 3.

At the second

pool

carnival on Friday, 14th July: