|

surfresearch.com.au

ancient hawaiian surfboards: #9 |

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

|

10.EARLY 21st CENTURY ANALYSIS OF HAWAIIAN SURFBOARDS : CATER

| home | catalogue | history | references | appendix |

Of these, the work of Ben Finney (1959, 1966, 1996) has significantly added to Blake's analysis.

Blake wrote (5) in The Hawaiian Surfboard (1935) ...

Here

is an interesting comment on surf riding to be found in Hawaiian

Folk Lore by Fornander(1):

"Here are the

names of that board and the surfs.

The board is

alaia,

three

yards long. (2)

The surf is kakala,

a curling wave, terrible, death dealing.(3)

The board is

Olo,

six yards long. (4)

The surf is opuu,

a non-breaking wave, something like calmness".(5)

This

passage shows the different boards best suited to different kinds of waves.(6)

The

alaia as the thin board was called, ranged from a few feet, a child's size,

to about twelve feet long for adults.(7)

The

larger one being about one and one half inches thick through the center,

levelling off on both top and bottom to about one-quarter inch at the edges.(8)

The

kakala, indicates a wave that steepens up and crashes over the shallow

coral.(8)

The

comparatively small size of the alaia board made it easy to handle in such

waves.

It

was made of the hardwood of the koa (9)and

breadfruit tree.(10)

The Olo, indicating the longer boards, was of wili wilIi wood (11), a porus light wood like balsa, in fact, wili willi is Hawaiian balsa, just as koa is Hawaiian mahogany, of which there are sixty-seven different kinds in the world. An alaia designed board of wili wilIi would not be strong enough, therefore, the Olo type was about six inches thick maximum, down the center of the board, and made of convex top and bottom so the edges beveled off to about one-half inch all around.(12)

The

Hawaiian chief, Pakai, was a famous surf rider around the 1830 period.(13)

His

two great surfboards are now in the Bishop Museum. (14)

Although

these two boards are of Olo design, long and thick, and of heavy koa wood,

I feel that koa was second choice for the making of this long board.

Wili

wilIi being generally used.(15)

I

also believe that while the wili wili board of Olo design was re-

Page 17.

(I

also believe that while the wili wili board of Olo design was re-) served

for the use of the chiefs, the koa board of Olo design was not restricted

to the alii (chiefs), but was for general use because of the scarcity of

wili wili wood and plentiful occurrence of koa. (1)

How

the Olo long board was especially adaptable to the swells or unbreaking

wave, will be clearly brought out in a later discussion on modern surfing.

(2)

Duke

Kahanamoku's answer to the reason for the old wili wilIi boards being reserved

for the chiefs is that it was a very scarce and valuable wood.

Therefore,

the chiefs had wili wili boards for the same reason that a man has a Rolls-Royce

automobile today, that he is wealthy and can afford it.(3)

Page18.

12. "the Olo type

was about six inches thick maximum, down the center of the board, and made

of convex top and bottom so the edges beveled off to about one-half inch

all around."

This report is apparently

based on the dimensions of the three known examples - two of koa wood and

one of non-native pine. .

As yet, no reference

records the thickness for an alaia or Olo board built from willi willi.

Given the reported

low strength of willi willi, it is possible that the extreme thickness

(compared to the alaia) was required to improve the structural integrity

of the board.

13. "The Hawaiian chief, Pakai, was a famous surf rider around the 1830 period."

14. "His two great surfboards are now in the Bishop Museum."

15. "Wili wilIi being generally used."

Page 18

The store of legends

pertaining to ancient surfriding being exhausted, I am fortunate in having

at hand the earliest writing of white men in these Islands that refer to

the sport. The oldest, of 1783 vintage, by Ellis, Captain Cook's historian,

leaves an account of how the Hawaiians of that time practiced surfriding.

It says:

"Native men,

and women alike, enjoyed it. In Kealakakua Bay (Hawaii) the waves broke

out about one hundred and fifty yards. Twenty or thirty natives, each with

a narrow board with rounded ends, would start out together from the shore

and battle the breaking waves to a point out beyond. The surfers would

then lay themselves full length upon the boards and prepare for the swift

return to shore, They would throw themselves in the crest of the largest

wave, and be driven towards shore with amazing rapidity. The riders must

ride through jagged opening in the rocks, and, in case of failure, be dashed

against them."

The boards used

by these natives were undoubtedly of the aleia or thin type.

The Olo, or long

thick board, would not be practical on so short a surf, and rocky a shore.

The long surf and unbroken swells are better suited to the Olo board.

Archibald Campbell,

in his work, Voyage Around the World, 1806-1812, refers to seeing

surfboards in the Sandwich Isles, ( now, the Hawaiian Islands). Of the

natives, he says:

"They often swam

several miles offshore, to ships, sometimes resting upon a plank shaped

like an anchor stock -and paddling with their hands, but more frequently

without any assistance what- ever. Although sharks are numerous in those

waters, I never heard of any accident from them, which, I attribute to

the dexter- ity with which they avoided their attacks."

Pages 33-34.

Ellis, in a work

of 1823, says: "After using, the surfboard is placed in the sun till perfectly

dry, then it is rubbed over with cocoanut oil, frequently wrapped with

cloth and suspended in some part of their dwelling house.

"There are few

children who are not taken into the sea by their mothers the second or

third day after their birth, and many can swim as soon as they can walk."

I can say that

many children, boys of about eight years old, can ride the waves on a surfboard.

True, they stay near shore, but master the same technique as their older

brothers.

The great regard

of the ancient Hawaiian for his surfboard, displayed by his care in drying

and oiling it and even wrapping it in 'tapa and hanging it in his house,

gives some idea of the value and high place the surfboard had in his life.

Next comes the

work of Malo, the Hawaiian historian, with translations by Emerson. Malo

was born in 1793, was known to be writing in 1832, and died in 1853. An

honest, conscientious writer, he devotes but a short chapter to surf riding

as practiced by the old Hawaiians. However, his work is invaluable in building

the chain of surfboard customs.

Malo says: "Surfriding

was a national sport of the Hawaiians, at which they were very fond of

betting, each man staking his property on the one he thought ;to be the

most skillful.

"With the bets

all put up, the surf riders, taking their boards with them, swam out through

the surf ;till they had reached the waters .outside the surf.

"The surfboards

were broad and flat, generally hewn out of koa. A narrower board was made

from the wood of the wili wili. One board would be one fathom in length;

one, two fathoms; and another, four fathoms or even longer.

Page 36.

"The surf riders

having reached the belt of water outside the surf, the region where the

rollers begin to make head,' awaited the incoming wave in preparation for

which they got their boards under way by paddling with their hands until

such time as the swelling wave began to lift and urge them forward.

"Then they speeded

for the shore until they came opposite to where was moored a buoy, which

was called a pau. If the combatants crossed the line of this buoy together,

it was a dead heat, but if one went by in advance of the others, he was

the victor ."

Malo wrote another

paragraph in his chapter on surfriding which Emerson could not translate,

but thought it meant that the victor was declared only after more than

one heat, or that the race consisted of several or many trips from outside

to the buoy or finish. I feel that ;this interpretation is correct. Anything

from three to ten rides would be an average race.

Emerson found

him over estimating dist,ances or sizes on two occasions. I believe Malo

meant yards when he used fath- oms. How many of you know how long a fathom

is? Six feet.

Malo's statement

that a "narrower board was made from the wili wili," bears out my theory

that the 010, or long type board, was not usually made of the hardwoods

from koa and breadfruit trees, but of the sof,t, light wood of the wi Ii

wili tree. Those koa boards of chief Paki's in the the Bishop Museum, are

really a bit too heavy, although handling well in the water, and riding

the big swells in a good manner. I choose, for the big waves, a hollow

board weighted with lead to make it steady. I find seventy pounds a good

weight for a hollow board for big surf.

I recently had

the privilege, and hard work, of restoring Paki's museum boards to their

original condition. For twenty years or more they had been hanging or tied

wi,th wire against the stone wall on the outside of the museum, covered

with some old reddish paint and rather neglected.

My inquiries

into the art of surfriding disclosed to me the the true value of these

two old koa boards. They are the only two ancient surfboards of authentic

010 design known to be in exist- ence today.

I made an appeal

to Mr. Bryan, curator of the museum, to restore the boards to their former

unpainted finish and begged a

Page 37.

more worthy location

for their display in the museum. Permission was refused by the directors

on the grounds that I might injure the e,rident antiquity of Paki's boards.

After two years, I made a second appeal, and was granted permission to

restore them and given promise of a more suitable location inside the building

to keep them.

In the restoration

of Paki's old boards, I discovered that they are undoubtedly much older

than anyone suspected. In fact, they were probably already: antiques when

Paki acquired them. I shall give my reasons for this inference.

Underneath the

old red paint was several coats of blue paint. and underneath ,that were

hard layers of a sand colored paint, and underneath that in many spots

was marine deck seam compound filling in worm eaten parts of the board.

On the largest board, the tail, in part, was rebuilt of California redwood

to give the board its original shape.

Paki, according

,to Stokes, was born on Molokai in 1808, and lived until 1855. It was probably

around 1830 when Paki was man enough to handle these big boards. The old

whaling ships were sometimes seen in Honolulu harbor then and the several

kinds of paint beneath the old red surface, also the ship's deck seam compound

and redwood tail patch were available even before

1830.

Therefore, I

assume that Paki dug up these two fine old dis- carded worm-eaten boards,

had the redwood patch put on one, the deck caulking compound and paint

on both, and painted them, so he could use them himself.

In their restored

condition, the worn holes and patches show clearly under the varnish finish.

Two fine examples of a now extinct design are these two old board on which

Chief Paki once rode the Kalahuewehe surf at Waikiki.

1t is said that

Pili would not go surfriding unless it was too stormy for anyone else to

go out. His reputation of going out only in big surf is the natural thing

when a man gets beyond his youth. Today, it takes big waves to get the

old timers out on their boards.

A bit of information

as to surfriding in other South Sea Islands is disclosed by Wilkes. He

says: "The King's Mile Is- landers use a small board in swimming in the

surf like that used in the Sandwich Islands." (Hawaiian.)

Page 38.

And Cordington

says: "In the Banks Islands and Torris Islands, and no doubt in other islands,

they use the surfboard."

It is apparent

to me that it remained for the old Hawaiians to put the art of the surfboard

on the highest level of develop- ment and popularity' it had ever reached

in the world, a much higher level than the sport occupies today. But it

is coming back and the future will see contests and surfriding that will

rival any that ,took place for the old Hawaiian kings.

Of surf riding

in 1853, an observer says: "Lahaina is the only place where surf riding

is practiced with any degree of enthusiasm, and even there it is rapidly

passing out of existence."

This writer referred

only to the Island of Maui, I believe. Here's a reference to the isolation

and quietness of Waikiki

in the early

days; the work of G. W. Bates, published in 1854: "Within a mile of the

crater's base (Diamond Head) is the

old village of

Waikiki. It stands in the center of a handsome coconut grove. There is

a fine bay before the village, in whose water the vessels of Vancouver

and other distinguished navigators have anchored.

"There were no

busy artizans wielding their implements of labor; no civilized vehicles

bearing their loads of commerce, or any living occupant.

"Benea'th the

cool shade of some evergreens, or in a thatched house reposed several canoes.

Everything was so quiet as though it were the only village on earth; and

the tennants, its only denizens.

"A few natives

were enjoying a promiscuous bath in a crystal clear stream that came directly

from the mountains.

"Some were steering

their frail canoes seaward; others clad simply in Nature's robes, were

wading out on the reefs in search of fish."

Page 39.

Aside from the

charm of Bates' description of old Waikiki it establishes the fact that

under those conditions, surfriding was, indeed a lost art. I feel, however,

that there was always surfrid- ing at Waikiki beach, on some kind of a

board. Waikiki's condi- tion in 1854 indicates that the great popularity

of the national pastime, surf riding, was but a memory.

John Dean Caton,

L.L.D., gives his observations on surf- riding at Hilo, Hawaii, in a volume

published in 1880, and throws light on the much argued points as to whether

the old surfriders rode the waves at an angle, or slid them, and whether

they stood upright upon the speeding surfboard.

Caton says: "One

instantly dashed in, in front of, and at the lowest declevity of the advancing

wave, and with a few strokes of hands and feet, es'tablished his position

(on the wave). Then, without further effort, shot along the base of the

wave to the ea!t- ward with incredible velocity. Naturally, he came towards

shore with ,the body of the wave as he advanced, but his course was along

the foot of the wave, and parallel with it, so that we only saw that he

was running past with the speed of a swift winged bird. He kept up with

,the progress of the breaking crest, which moved from west to east, as

successive portions 01 the wave took the ground (broke in shallow water)

."

There we have

an old time surf rider sliding the wave from

Page 41.

west to east in

grand style, jU&t as we do at Waikiki beach today, and they slid the

wave for the same reason we do today; that is, to get away from the breaking

or foaming crest of the wave.

Caton continues:

"As the big seas chased each other in from the open ocean, the west end

first reached the rocky bed, and the instant the bottom of the wave met

this obstruction, its rotary motion was checked, and immediately, the comb

on the top was formed, so that the foamy crest seemed to run along the

top of the wave from west to east, as successive portions of it reached

the rock bottom."

This explains

why the wave breaks at a certain place first, if you follow Caton. The

riders he saw had to slide the wave to get away from the break and keep

off the rocks.

Relative to standing,

Caton says: "As soon as the bather had secured his position, he gave a

spring, and stood upon his knees upon the board, and just as he was passing

us, when about four hundred feet from the little peninsula point where

we stood, he gave another spring and stood upon his feet, now folding his

arms upon his breast, and now swinging them about in wild ecstasy, in his

exhilarating flight."

So they stood

upon the surfboard in olden times just as we do today. Caton describes

these boards as being about one and one-half inches thick, seven feet long,

coffin shaped, rounded at the ends, chamfered (beveled) at the edges; about

fifteen inches wide at the widest point near the forward end, and eleven

inches wide at the back end.

Clearly, boards

of the aliea, or thin design, were usually made of koa or wood of the breadfruit

tree. At Waikiki, today, a board of tHe above dimensions is used only by

children up to twelve years old.

The surf bathers

Caton speaks of were certainly of the old school, as he says they stripped

to their breach cloths or malos, before going in the water.

Caton found the

natives could not explain why they were propelled sh.oreward with such

astonishing speed, nor could Mr. Ca~n explain it himself, nor could his

friends. He hoped that someday, someone would study the question and find

an answer to it.

The answer is

relatively simple. Gravity does the trick. The

Page 42.

front slope of

the wave on which one slides presents a down-hill path, while the friction

of the slippery board against the water is very small. It's the same as

skiing on a snow-covered hill, and there is no doubt as to what make&

one slide down a hill on skis. However, in skiing, one can start down hill

from a stationary posi- tion, while in surfriding some momentum must first

be attained ,to catch up with the incoming swell. This is accomplished

by pad- dling the board with the hands and arms.

In 1822, a publication,

the Hawaiian Annauls, has an inter- esting comment to make on surf riding:

"The principal

sport is surf riding ...The people of Kauai generally held the credit of

exceeding all others in the sports of the Islands. At one time, they sent

their champion surf rider to compete with the chiefs in the sport on Hawaii,

who showed them man's ability to shoot, or ride with the surf without a

surfboard."

So the popular

and much seen United States sport of "body surfing" is an old Hawaiian

custom.

Some feel that

the cooler climate of Kauai is why the greatest athletes come from those

shores.

Duke Kahanomoku

calls attention to the fact that to catch a wave for "body surfing," in

the true Hawaiian manner, it is necessary to swim before the breaker using

the modern crawl stroke, with a flutter kick. As a boy, Duke "body-surfed"

and swam the crawl stroke before the world had a name for it. Also the

ancient Hawaiians, adapt at "body surfing," swam the crawl stroke as part

of the sport; therefore, the origin of the so-called new craw swimming

stroke dates back to antiquity.

The crawl kick

was also used in conjunction with the short three-foot surfboards used

at Waikiki beach around the 1903 period.

I can say Duke

is the world's outstanding body-surfer. I have watched him ride the surf

in perfect style here in Hawaii and in the mainland United States, without

a board. On one occasion at Balboa, California, I saw him body-surf a big

comber for over two hundred yards.

When body surfing,

Duke can slide the wave left or right at will. This greatly surprised the

Australians as they had never seen it done before, although they were familiar

with shooting the waves without a board.

Page 43.

The Australians

are very clever at this sport; it is the leading water pastime at their

beaches.

In 1891, Bolton

wrote: "The sport of surf riding, once so universally popular, and now

but little seen."

As seen on the

Island of Niihau, Bolton describes surf riding: "Six stalwart men assembled

on the beach, bearing with them their precious surfboards. These surfboards,

in Hawaiian, 'papahee- nalu,' or 'wave sliding boards,' are made from the

wood of the veri veri, or breadfruit 'tree. They are eight or nine feet

long, fifteen to twenty inches wide, rather thin, rounded at each end,

and carefully smoothed. The boards are stained black, are fre- quently

rubbed with coconut oil, and are preserved with great solicitude, sometimes

wrapped in cloths. Children use smaller boards. ..Just as a high billow

was about to break over them, pushed landward in front of the combers.

They drove him for- ward ont9 the. beach, or into shallow water."

.Here we find

the same kind of surfboard, the aliea type used in Niihau, as seen 1?Y

Caton in Hawaii, at the other end of the group of Hawaiian Islands.

In the Ha~ian

Annuals, published in 1896, is an account of ancient surfriding, prepated

by a native of the Kona district of Hawaii, familiar with the subject.

The valuable work was trans- lated by Nakoina, a former surfrider.

I feel this to

be the finest contribution on old surfriding in existence and am sure the

"native from Kona" knew the art of surfriding well. Her:e is the account:

"Surfriding was

one of the favorite sports, in which chiefs, men, women and youths took

a lively interest. Much valuable time was spent by them in this practice

,throughout the day. Necessary work for the maintenance of the family,

such as farming, fishing, mat and tapa making, and such other household

duties required of them and needing attention, by either head of the family,

was often neglected for the prosecution of the sport. Betting was made

an accompaniment thereof, both by .the chiefs and the common people, as

was done in all other games, such as wrestling, foot- racing, holua, and

several other games known only to the old Hawaiians. Canoes, nets, fishing

lines, kapas, swine, poultry and all other property was staked, and in

some instances, life itself was put as a wager. The property changing hands

and personal

Page 44.

liberty or even

life itself sacrificed according to the outcome of

the match, the

winners carrying off their riches, and the losers

and their families

passing to a life of poverty or servitude. There

are only three

kinds of trees known to be used for making boards

for surfriding.

the wili wili, the ulu or breafruit, and the koa.

"Tree and mode

of cutting: The uninitiated were naturally careless or indifferent as to

the method of cutting the chosen tree;

but among those

who desired success upon their labors, the follow-

ing rites were

carefully observed.

"Upon the selection

of a suitable tree, a red fish called kumu, was first procured, which was

placed at its trunk. The tree was then cut down, after which a hole was

dug at its root and the fish placed therein with a prayer as an offering

in payment thereof. After this ceremony was performed the tree trunk was

chipped away from each side until reduced to a board approximately of

the dimensions

required, when it was pulled down to the beach and placed in the halau

(canoe-house), or other suitable place con- venient for its finishing work.

"Finishing process.

Coral of the corrugated variety which could be gathered in abundance along

the sea beach and a rough kind of stone called 'oahi' were commonly used

articles for reduc- ing and smoothing the rough surface of the board until

all marks

of the stone

adze were obliterated. As a finishing stain, the root

of the ti plant

called 'mole-ki' or the pounded bark of the kukui, called 'hili,' was the

mordant used for a paint made with the root

of burned kukui

nuts. This furnished a durable, glossy, black finish, far preferable to

that made of the ashes of burned cane leaves or amau fern which had neither

body nor gloss."

Emerson says

of the protective finish of the canoe and surf- board: "This Hawaiian paint

had almost the quality of lacquer. Its ingredients were .the juice of a

certain euphorbia, the juice of the inner bark of the root of the kukui

tree, the juice of the bud of the banana tree, together with a charcoal

made from the leaf of the pandanus. A dressing of oil from the nut of the

kukui was

finally added

to give a finish."

I am told by

Cottrell, who saw the performance, that a surf- board made of wili wili

wood was buried in mud, near a spring, for a certain length of time to

give it a high polish.

I should say

that the mud entered the porous surface of the

Page 45.

wi Ii wili board

acting as a good "filler" for sealing up the surface. When the board was

then dried out the mud surface became hard and was polished and oiled to

a fine waterproof finish.

"Before using

the board, there were other rites or ceremonies to be performed for its

dedication. As before these were disre- garded by the common people, but

among those who followed the making of surfboards as a trade, they were

religiously observed.

"There were .two

kinds of boards for surf riding. One was called Olo, and the other the

alaia, known also as omo. The Olo was made of wili wili, a very light bouyant

wood, some three fathoms long, two to three feet wide, and from six to

eight inches thick along the middle of the board lengthwise, but rounding

to- ward the edges on both upper and lower sides. It is well known that

the 010 was only for the use of the chiefs; none of the com- mon people

used it. They used the alaia, which was made of koa or ulu. Its length

and width was similar to the 010 except in thickness, it being about one

and a half inches along its center.

"Breakers. The

line of breakers is the place where the outer surf rises and breaks at

deep sea. This is called kulana nalu. Any place nearer or closer in where

the surf rises and breaks again as they sometimes do, is ca1led the ahua.

"Methods of Surfriding.

The swimmer taking position at the line of breakers waits for the line

.of surf. As before men- tioned, the first one is a1lowed to pass by. It

is never ridden be- cause its front is rough. If the second comber is seen

to be a good one, it is sometimes taken, but usua1ly the third or fourth

is the best, both from the regularity of its breaking and the foam calmed

surface of the sea through the travel of its predecessors. In riding with

the 010 or thick board on a big surf, the board is pointed landward and

the rider mounting it paddles with his hands and impe1ls with his feet

to give the board a forward movement and when it receives the momentum

of the surf and begins to rush downward, the ski1led rider will guide his

course straight or obliquely, apparently at wi1l, according to spending

character of the surf ridden, to land himself high and dry on the beach

or dis- moTt on nearing it as he may elect. This style of riding was called

kipapa. In using ,the 010 great care had to be exercised in its management

lest from the height of the wave if coming in direct the board would be

forced into the face of the breaker

Page 46.

instead of floating

lightly and riding on ,the surface of the water in which case the wave

force being spent reaction throws both rider and board into the air.

"In the use of

the Olo, the rider had to swim out around the

line of surf

to obtain position or be conveyed thither by canoe. To swim out through

the surf with such a buoyant bulk was not possible, though it was sometimes

done with the thin boards, the alaia. The latter are good for riding all

kinds of surf and are much easier ,to handle than the 010.

"Expert Positions.

\T arious positions used to be indulged in by experts in this aquatic sport,

such as standing, kneeling and sitting. These performances could only be

indulged in after the board had taken on ,the surf momentum and in the

following man- ner. Placing the hands on each side of the board close to

the edge, the weight of the body was thrown upon the hands, and the feet

brought up quickly to the kneeling position. The sitting posi- tion is

obtained in the same way, though the hands must not be removed from the

board till the legs are thrown forward and the desired position is secured.

From kneeling the standing position was obtained by placing both hands

again on the board, and with agility, leaping up to the erect altitude,

balancing the body on the swift, coursing board with outstretched arms."

I can detect

only one error in the work. That writer says the 010 board of wili wili

was "two or three feet wide." This makes the board too wide to paddle comfortably

and also too wide to give a good performance. The width of the 010 board

was from one to two feet wide, instead of from two to three. I also infer,

from that error, the writer to be unfamiliar with the wi Ii wili, or chief's

board. It is also evident from his writing that the 010, or long thick

board, was not made of koa and ulu, but of only wili wili. Therefore, PaKi's

boards of 010 design and made of koa are an exception and not the rule.

They really are too heavy to please the average surfrider. On the other

hand, we have today an enthusiastic and skillful surf rider, Northrop Castle,

who has a board weighing more than either of Paki's. Castle's board weighs

about two hundred pounds, and he likes it.

The popularity

of betting on the old contests is discussed before all else. This emphasizes

its importance in ancient times

Page 47.

and that in turn

gives a better insight into the place surfboard racing had in their lives.

In the American

Anthropologist, 1889, we find reference to surfriding: "The riders sometimes

also raced to the kulano, or starting place. Standing on the boards as

they shot in was by no means uncommon. Men and women both took part in

this de- lightful pastime, which is now almost a lost art."

This establishes

the fact that some of the races were started from shore, the men paddling,

or racing out to ,the starting of the breakers.

The above work

also says: "Racing in the surf is called hie- eie-nalu, 'hie-eie' meaning

to race and 'nalu' meaning surf. Two champions will swim out to sea on

boards, and the first on arriv- ing on shore wins."

Andrews gives

the names 010 and wili wili, for a "very thick surfboard made of wili wili,"

and o-ni-ni as a "kind of surfboard," also "pa-ha" as a name for a surfboard.

In Andrew's mind

there evidently was established the belief that the wili wili wood was

the accepted wood for making the 010 or long thick surfboard.

Brigpam, in Preliminary

Catalogue, says: "Surfboards were usually made of koa, flat with a slightly

convex surface, rounded at one end, slightly narrowing towards the stern,

where it was cut square. Sometimes ,the 'pa-pa' (surfboard) was made of

a very light wi Ii wili and then made;ooQ1Q. (narrow). In size, they varied

from three to eighteen feet in length and from eight to ten inches in breadth,

but some of the ancient boards were said to have been four fathoms long."

There again,

we have an entirely different writer, who actually says that the Olo, or

narrow board, was made of the light wili wilIi wood and up to eighteen

feet in length.

Page 49.

A selection of photographs,

Third set between pages 48 and 49, includes Jacques Arago's (or Alphonse

Pellion's) :

"The Houses of

Kraimokou, circa 1819." and the caption by Blake ...

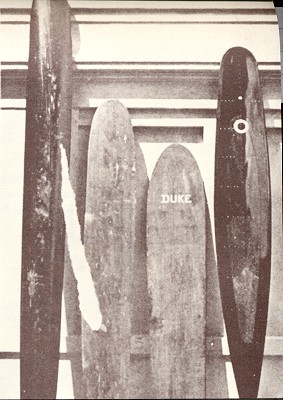

This third set also includes a photograph of a selection of four surfboards and the caption

In another magazine,

The

Pan Pacific, an article called "Surf- riding-The Royal and Ancient

Sport," by this writer, discloses the motif for trying to change the then

popular and satisfactory type of surfboards. Written in 1930, the article

reads in part:

"Strange as it

may seem, three old-style Hawaiian surfboards of huge dimensions and weight

have hung on the walls of the Bishop Museum -in Honolulu for twenty years

or more without anyone doing more than wonder how in the world these great

boards were used, and were they not too long and heavy to be practicable;

"I too, wondered

about these boards in the museum, wondered so much that in 1926 I built

a duplicate of them as an experiment, my object being to find not a better

board, but to find a faster board to use in the annual and popular surfboard

paddling races held in Southern California each summer. This surfboard

was sixteen feet long and weight 120 pounds. When I appeared with it for

the first time before 10,000 people gathered for a holiday and to watch

the races, it was regarded as silly. Handling this heavy board alone, I

got off to a poor start, the rest of the field gaining a thirty-yard lead

in the meantime. It really looked bad for the board and my reputation and

hundreds openly laughed. But a few minutes later it turned to applause

because the big board led the way to ,the finish of the 88O-yard course

by fully 100 yards.

"My dream was

to introduce, or revive, this type of board in Hawaii where surfboard racing

and riding is at its best. This seems to have materialized, for, quoting

Dr. D'Eliscu of the

Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 'The old Hawaiian surfboard

has again made its appearance at Waikiki beach modeled after the boards

used in the old days. A practice trial was held yesterday at the War Memorial

Pool, and to the surprise of the officials, the board took several seconds

off the Hawaiian record for one hundred yards.' This was the racing model.

The riding model, 'Okohola,' came a month later, December, 1929.

"What pleases

me most is the way the board can catch the ground swells on the reef so

much farther out to sea than the

Page 59.

ordinary surfboard.

So my faith in the ideas of the old Hawaiians has been rewarded by the

performance of a board designed by them thousands of years ago.

"Dad Center,

kamaina and famous surf rider, says that when he was a boy on the Island

of Maui, a native took a long board out in storm surf and rode the swells

till they broke near shore. So there we have a complete substantiation

of what the museum type board suggests. Dad continues, 'That was in the

'90's and was about the finish of the long board on that island. They were

occasionally used, however, more as a novelty at Waikiki, until around

1900.

I "Around 1900

the art of surfriding was almost obsolete. Even at Waikiki beach there

was very little as most people lived in Honolulu and it was difficult to

get to Waikiki. Interest revived and in 1907 a group of prominent men,

led by Alexander Hume Ford, organized and formed the Outrif{ger Canoe Club.

The

charter reads:

'We wish to have a place where surfboard riding' may be revived and those

who live away from the water front

may keep their

surfboards. The main. object of this club being. to give an added and permanent

attraction to Hawaii and make

the Wajkiki beach

the home of the surfrider'."

I have some notes

relative to the 1900 period written by Wm. A. Cottrell, one of the early

surfriders at Waikiki. He says: "Princess Kaiulaini was an expert surf

rider around 1895 to 1900. She rode a long 010 board made of wi Ii wili.

She apparently was the last of the old school at Waikiki.

"About 1903 we

used a short board a few feet long, rather thin and wide, like a washboard.

From 1903 to 1908 marks the true revival of the sport. encouraged by the

following old timers: Wm. Dole, Dudie ¥iller. Duke Kahanamoku, Harold

Castle, Geo. Freeth. Dad Center, Kauha, Ho1stein, Jordan, Lishman, Atkin-.

son, "Steamboat" Bill, Winter, Brown. Kaupipko, Mahelona, Kea- wamaki,

May, Curtiss, Hustace, Roth, Aurnolu and McKenzie. Some of these men are

riding today. Many of the above men were members of ,the first club, called

the 'Waikiki Swimming Club'; the charter members were Duke Kahanamoku,

Knute Cot- rell, and Ken Winters. This club was an incentive which influenced

the foundation of the Outrigger Canoe Club in 1907 and the Hui Nalu along

about the same time."

Page 60.

Reprinted in 1983

by Bank Wright as

Blake, Tom: Hawaiian

Surfriders 1935

Mountain and Sea

Publishing, Box 126 Redondo Beach California 90277 1983

Embossed hard cover

with adhesive image.

DeLa Vega

(2004) notes "Joel Smith's edition was used to create these plates.",

page 38.

2. Blake,

Tom: Hawaiian Surfriding

Nothland Press,

Flagstaff,Arizona, 1961

Soft cover, 41 pages

(without page numbers), 58 black and white plates, 3 black and white ???

3. Blake's

work has been extensively quoted by many subsequent surfing historians.

To detail a complete

inventory would be pointless - almost every book or magazine article that

discusses ancient Hawaiian surfing either quotes Blake directly or his

sources.

The following works

(excluding those of Ben Finney) are readily available.

Nat, Warshaw, Lueras,

Carroll,

4. Ben Finney

originally prepared his research for a masters thesis in anthropology.

The quality of his

work has set the benhmark for all following historians of surfriding.

Finney, Ben: Surfing

in Ancient Hawaii

The Journal of

Polynesian Society

December 1959 Volume

68 Number 4 pages 327 - .347

Finney, Ben: The

Development and Diffusion of Modern Surfing

The Journal of

Polynesian Society

December 1960

Volume 69 Number 4 pages 314 - .331

Finney, Ben and Houston,

James D. : Surfing – The Sport of Hawaiian Kings

Charles E.

Tuttle Company Inc.

Rutland, Vermont

and Tokyo, Japan. 1966.

Second printing

196?, Third printing 1971.

Finney, Ben and Houston,

James D. : Surfing – A History of the Ancient Hawaiian Sport

Pomegranate

Books

P.O. Box 6099

Rohnert Park, CA 94927

Soft cover,

117 pages, 20 b/w photographs, 24 b/w illustrations, Appendices,

Notes, Bibliography.

5. All reproduced

text is in Bell 14 point and not in quotation marks or italics.

My text is in Arial

12 point.

For screen clarity,

the reproduced text and my own work has been adjusted to my standard online

format.

Paragraphs are indicated

by a spaced line (replacing indentation) and each sentence takes a new

line.

Page 17

1. Fornander,

Abraham: Forlander Collection of Antiquities and Hawaiian Folk Lore

: Translations by Thomas G. Thrum.

Bishop Museum Press,

Honolulu, 1919-1920.

Memoirs of the Bernice

Pauahi Bishop Museum, Volumes 4, 5 and 6.

DeLa Vega

(2004) notes "Tom Blake considered this collection one of the most comprehensive

looks at the legends and chants of ancient Hawaii.", page 19.

2. "alaia,

three yards long"

One yard equals

three feet, 36 inches or 92 cm.

The reported alaia

is approximately 9 feet or 275 cm long.

This conforms with

existing examples of the board.

3. "kakala,

a curling wave, terrible, death dealing."

The wave is characterised

by its steep face and hard breaking curl.

It is typically

found in the common beach break.

4. "Olo,

six yards long."

One yard equals

three feet, 36 inches or 92 cm.

The reported Olo

is approximately 18 feet or 550 cm long.

This reasonably

conforms with two know existing examples of the board, hower both are in

koa wood..

5. "opuu,

a non-breaking wave, something like calmness."

The wave is characterised

by its gentle sloping face.

A noted feature

of surfing conditions at Waikiki, Ohau, it is favoured by canoe surfers.

6. "This passage

shows the different boards best suited to different kinds of waves."

Although this is

generally correct, the performance of any surfboard is a function of the

rider's statue and skill.

7. "The

alaia as the thin board was called, ranged from a few feet, a child's size,

to about twelve feet long for adults."

Buck (1959)

notes "The Bishop Museum collection consists of 25 boards ranging from

a child's board of breadfruit wood (Bishop Museum catalogue number

C. 5966), 34.25 inches long, weighing 2 pounds 10 ounces to a modern

redwood board, 17 feet 2 inches long, weighing 174 pounds." Page 384.

While Blake chiefly

characterises the alaia as "the thin board" with a wide range of

lengths and widths,

Buck

(1957) and Finney (1959) make a

distinction based on riding position - prone ("body-board') or standing

models ("true surfboards"), based largely on length.

Buck (1957)

page 384

Finney (1959)

pages 331 and 333.

This distinction

presents several difficulties.

1. Firstly, it requires

the observer to determine the riding position of any particular board based

on their surf riding experience.

As noted above,

the performance of any surfboard is a function of the rider's statue and

skill.

2. While early reports

indicate that solid board riders did ride in the standing position, it

is unclear if this was practised as an exclusive preference.

The ancients may

have ridden a particular wave in a variety of positions - prone, kneeling,

drop-knee, sitting and standing - adjusting to changes in the wave's shape

and velocity.

3. There is no such

distinction in the early literature.

Commentators, such

as Malcom Gault-Williams (2005) have used the term paipo

(page 95) to indicate prone boards, but this word does not appear in any

list of ancient Hawaiian words.

See Finney and

Houston (1996) Appendix A, pages 94 to 96.

4. The principal

feature for a board to be ridden in a standing position is possibly the

width.

5. All these commentators

fail to note the major advantage of a board with larger volume - a significant

improvement in padding speed and distance.

It is probably reasonable

to assume that, regardless of the statue and skill of the rider, that smaller

boards were mostly used at surfing breaks close to shore, while larger

boards had the potential to ride waves breaking a considerable distance

from shore.

8. "The larger

one being about one and one half inches thick through the center, levelling

off on both top and bottom to about one-quarter inch at the edges."

This indicates that

the maximum thickness for the alaia was one and one half inches, considerably

thinner than all subsequent surfboard designs.

9. "The kakala,

indicates a wave that steepens up and crashes over the shallow coral."

As noted, this type

of wave is typically found in the common beach break.

Surfing breaks occuring

on coral reefs are generally limted to equatorial regions.

10. "koa" (Acacia

koa)

Tommy Holmes' authorative

work, The Hawaiian Canoe (1981, 1993), writes extensively about

koa and its use of by ancient Hawaiian canoe builders.

Significant sections

are of interest in a discussion of ancient Hawaiian surfboards.

Holme's work is

fully referenced, however his notes are not included in this paper.

Holmes, Tommy :

The

Hawaiian Canoe - Second Edition

Editions Limited,

PO Box 10558 Honolulu, Hawaii 96816.

First Edition 1981.

Second Edition 1993. Second Printing 1996.

Koa

A

magnificent and totally unexpected gift awaited discovery by the settlers

reaching Hawai'i.

The

islands were blessed with extensive forests of what would come to be called

koa, trees of extraordinary size that were found nowhere else in the world.

These

trees would provide wood of remarkable durability out of which the Hawaiian

would shape his canoes.

For

some 1500 years the Hawaiian people lived in delicate balance with their

environment, the trees they used being replaced by natural regeneration.

Contact

with the west shattered this fragile balance; in the span of a few decades

koa began a radical decline that has continued even to the present day.

"Their

huge trunks and limbs cover the ground so thickly that it is difficult

to ride through the forest, if such it can be called," writes E.F. Rock

in 1913 of a once beautiful koa forest in Kealakekua, South Kona.

Rock,

a botanist, goes on to note of this macabre forest scene that "90 per cent

of the trees are now dead, and the remaining 10 per cent in a dying condition."

In

1779, a little over one hundred and thirty years before Rock's observations,

Lt. Charles Clerke who was with Captain Cook tells of wandering through

the koa forest above Kealakekua: "Some of our Ex- plorers in the woods

measured a tree 19 feet in the girth and rising very proportionably [sic]

in its bulk to a great height, nor did this far, if at all, exceed in stateliness

many of its neighbours; we never before met with this kind of wood."

Similarly,

Archibald Menzies in 1792 describes the same area: "The largest trees which

compose this vast forest I now found to be a new species of mimosa [koa].

..I measured two of them near our path one of which was seventeen feet

and the other about eighteen feet in circumference, with straight trunks

forty or fifty feet high. ..as we advanced, the wood was more crowded with

these trees than lower down where both sides of the path had been thinned

of them by the inhabitants."

Page

Acacia

koa, once undisputed monarch of the forests of Hawai'i, probably evolved

from seeds hitchhiking to Hawai'i in the bowels of some storm-blown bird

or through some other capricious act of the winds and seas.

In

an environment that was comparatively free of competitors and predators,

koa proliferated to where it was once-after 'ohi'a- the second most common

forest tree in Hawai'i.

It

has been estimated that today there is standing probably not much more

than ten percent of the amount of koa that existed at the time of Cook's

arrival; presently non-native species make up the majority of the forests

of Hawai'i.

Page

Koa

sometimes reaches massive proportions.

Tall,

straight koa trees up to 20 feet in circumference were seen by a number

of Europeans visiting Hawai'i in the late 1700's and early 1800's.

One

legend reputes a koa tree with a straight trunk as high as 120 feet, and

Emerson notes ten men were required to encompass another mammoth koa tree

from which a canoe was to be hewed. Though these dimensions are probably

exaggerated, there undoubtedly were some quite large koa trees.

Straight

trunks in excess of 70 feet were not unheard of; and while never plentiful,

one can still find today an occasional 50- t060-foot straight-trunked koa

tree.

In

1977 a 62-foot log was felled in the Honomalino forest above Kona, from

which a ten-man, 58-foot canoe has been made.

Of

old, certain areas such as the mountains above Hilo and Kona and the slopes

of Haleakala produced such an abundance of high quality canoe logs that

a very disproportionate amount of the total number of canoes throughout

the islands came from these sites.

At

Keauhou Ranch on the island of Hawai'i there stands what is considered

to be the largest koa tree in the world. Its trunk measures some 12 feet

in diameter and 371/2 feet in circumference.

Though

the trunk only rises about 30 feet before branching, its topmost branches

tower 140 feet above the ground.

The

tree is probably four hundred to five hundred years old.

Page

Koa

For Canoes

Early

Hawaiians, and canoe builders in particular, possessed an especially detailed

knowledge of differing physical characteristics of woods, primarily of

Acacia koa.

In

the absence of modern-day botanical classification techniques, the canoe

builder devised his own very sophisticated system for classifying koa.

Through

analysis of a tree's trunk shape and dimensions, bark, grain, and branching

patterns, a canoe builder was able to identify each koa tree as being of

a certain type.

Beyond

the obvious gross physical characteristics of a koa tree, the ancient canoe

builder was most concerned with the grain, for well he knew that each tree

possessed distinct grain characteristics. While today's botanist will tell

you that Acacia koa is Acacia koa, he will observe that there is, besides

the more obvious differences in physical characteristics, a remarkable

range in the density from one tree to the next, and from one stand to the

next.

The

density of koa ranges from a low of about 30 pounds per cubic foot to a

high of 80 pounds per cubic foot.

In

some cases there will even be a significant range of grain density within

the same tree.

It

was apparently this maverick and obscure feature of koa wood that most

plagued the canoe builder.

Page 29

While

the Hawaiian did not think in terms of pounds per cubic foot, he did develop

a system of grain classification that was for all practical purposes comparable

to a botanist's grain density scale.

Low

density koa (roughly 30 to 45 pounds per cubic foot) was to the canoe builder

generally soft, lightweight, and yellowish.

He

called it koa la' au mai' a (banana- colored koa) and valued it for its

lightness as wood for paddles, but rarely used it for canoes.

Another

name for this type of koa wood was koa' awapuhi, literally, "ginger koa,"

which was regarded as female by the Hawaiians.

Mid-range

density koa (40 to 60 pounds per cubic foot), reddish to brown, was overwhelmingly

favored for making canoes, primarily because of its durability, and strength-to-weight

relationship. Koa at the high end of the density range (60 to 80 pounds

per cubic foot) was almost black in color and extremely heavy.

The

wood of this type of tree was called koa 'i'o 'ohi'a (hard 'ohi'a-like

grain) and was usually avoided for canoes because the wood was heavy and

hard to work.

On

the occasion when a canoe was made of this kind of koa it was said that

it "will never lose its heaviness until. it is smashed."

This

contrasts to the typical koa canoe that over the years loses weight due

to water loss from the wood.

Noting

the tendency of koa to crack and check, canoe builder Z.P.K. Kalokuokamaile

said that the canoe maker of old had "to be very careful for the grain

of some trees lie [sic] all in the same direction."

(Note that one would

expect "the tendency for koa to crack and check" to be an important

concern to the builder using this timber for surfboards, it is not mentioneed

in any of the traditional sources.)

Further

identification of a tree was made through its bark.

Unfortunately,

only two types are recorded.

Kaekae

was a whitish bark that generally covered a tall, handsome tree, indicating

a straight grain of the la' au mai' a variety.

This

type of tree, according to Kalokuokamaile, made "a very light canoe and

floats well after it is built and put into the sea."

Maua

on the other hand, was a dark red bark that typically sheathed the tough,

heavy, black-grained ~i'o 'ohi'a, of which "the grain of the wood twists

forward and back.

This

is hard to make into a canoe."

Trunk

shape and dimensions, and branching patterns provided the canoe builder

with his most common means of identifying different types of koa.

Holmes then records

a list of twenty-one terms still known that were used in identifying koa

wa'a (koa for canoes).

Page 30

10. "breadfruit tree." (ulu) (Artocarpus incisus)

11. "wili wilIi wood" (Erythrina sandwicensis)

In a section titled Other Woods, Holmes discusses the use of breadfruit and willi willi in canoe building.

Fornander

notes that besides koa, "three other kinds of wood were used in the olden

time for building canoes, the wiliwili, kukui (candle-nut tree), and ulu

(breadfruit tree).

The

wiliwili is yet being used.

The

kukui is not much seen at this time.

The

ulu is used for repairing a broken canoe

"

Handy comments that the early Hawaiian settlers found kukui "to be one

of their most valuable assets, perhaps the chief of which lay in the fact

that the trunks of large trees could be hollowed into superb canoe hulls."

Soft,

light and easily worked, breadfruit, kukui and wiliwili were especially

favored as play or training canoes particularly for young aspiring canoeists

or women.

The

"baby" or training canoes rarely exceeded 20 feet in length and usually

were in the 10 to 15 foot range.

Of

the light woods, breadfruit was apparently least used; not only was the

breadfruit tree fairly rare and needed as a food source, the one variety

available to the Hawaiians was usually unsuitable in girth and height for

making canoes.

Holmes' comments

probably account for the restricted use of breadfruit for surfboard building,

certainly for larger boards.

Of

wiliwili, Fornander notes that "it was also made into canoes, provided

a tree large enough to be made into a canoe can be found; but it is not

suitable for two or three people, for it might sink in the sea.

But

it must not be finished into a canoe while it is green; leave it for finishing

till it has seasoned, then use it."

The essential requirement

that the timber be seasoned before finishing is not reported in any of

the accounts of early surfboard construction.

Emerson

says of softwood wiliwili canoes that: "If not sufficiently durable and

resistant to the powerful jaws of the shark, they were at least easily

manipulated and very buoyant, and made a cheap and on the whole a very

serviceable canoe for ordinary purposes."

Degener,

in his book Flora Hawaiiensis, noted that in the early part of this

century canoes of wiliwili were not in "favor because of the belief that

sharks preferred to follow this particular wood." The limited literature

on canoes made from softwoods tends to support the ancient Hawaiian's concern

for the greater vulnerability of light wood canoes to occasional shark

attacks.

These

beliefs might seem to conflict with the many reports of the use of willi

willi for ama (outrigger floats).

Note that such beliefs

would certainly appear a disincentive to use willi willi for surfboard

building and there is no consideration of this in the available literature..

Wiliwili

canoes are almost always referred to in the literature as near-shore, play

or training canoes. I'i notes that as a young boy he "had learned a little

about paddling a canoe made of wiliwili wood that his parents had provided

for him."

The restriction

of willi willi to "near-shore, play or training canoes" is possibly a reflection

on the low strength of the timber, the ancient Hawaiians distrustful of

its performance in the open sea conditions.

Wiliwili,

by some accounts, was never very plentiful.

Kalokuoka-

maile notes that "in the olden days. ..there were very few places in which

this tree grew." This is somewhat at odds with botanist W. E. Hillebrand,

who wrote that wiliwili was "much more common formerly than now."

It

was said by some that Ka'u was the best place for wiliwili.

Today

wiliwili can be found flourishing in certain areas.

The

author has visited a grove of wiliwili above the Makena area on Maui that

comprises several hundred acres.

Many

of the trees are 3 to 4 feet in diameter with trunks often rising 15 to

20 feet high before branching.

Other

sizeable stands of wiliwili dating from precontact times can still be found

in the Pu'uanahulu, Pu'uwa'awa'a and KaIapana areas of Hawai'i.

Smaller

populations are also found on Kaua'i behind Kekaha, in west O'ahu, south

and west Moloka'i, Kaupo on Maui, Ka'u on Hawai'i and on Kaho'olawe.

Emerson

makes an intriguing reference to a certain kaukauali'i (mi- nor chief)

who, in the time of Kamehameha I, constructed a vessel (moku) out of a

single huge wiliwili tree.

He

named this craft after himself, 'Waipa'.

It

was partly covered or decked over, but had no outrigger, being kept upright

by ballast.

It

had a single mast and sailed with Kamehameha's fleet to Oahu." It is not

unlikely that such a craft was built.

After

contact there were a number of Hawaiians experimenting with new types of

craft.

By

way of reference, the largest wiliwili tree known, located on Pu'uwa'awa'a

Ranch is, at breast height, almost thirteen feet in circumference, and

fifty-five feet high.

Kenneth

Emory, dean of Pacific anthropologists, records an informant who told him

in 1937 of the Hawaiians training wiliwili trees to grow tall and straight

before crowning by constantly trimming off side branches.

Page 23.

Holmes also includes

a discussion of the use of non-native timbers, washed ashore on the Hawaian

islands.

The use of such

timber by ancient surfboard builders can not be discounted.

Drift

Logs

The

gods must surely have smiled on the Hawaiian people, giving them yet another

special source of canoe logs: giant redwood, fir, pine and other kinds

of tree trunks that drifted from the northwest coast of America to the

shores of Hawai'i.

W.

T. Brigham, one-time curator of the Bishop Museum, notes that "many of

the largest and most famous double canoes of the Hawaiians were hewn from

logs of Oregon pine brought to the shores ofNiihau and Kauai by the waves.

I

myself saw dozens of such logs in 1864, some of great size, some bored

by Teredo, others covered with barnacles, along the shores ofNiihau."

Similarly

James Hornell notes that, "in Hawaii giant logs of Oregon pine occasionally

drifted ashore; these were greatly prized, for they were often so large

as to serve as entire hulls without the need of raising the sides by means

of planks sewn on; the difficulty was to obtain a pair of approximately

equal size; sometimes a log was kept for years before this aim was achieved."

It

was as if nature had compensated for the chronic canoe log shortage on

Kaua'i and Ni'ihau, for that was where most of these drift logs landed.

Captain

George Vancouver notes that "the circumstance of fir timber being drifted

on the northern sides of these islands is by no means uncommon, especially

in Attowai [Kaua'i], where there then was a double canoe, of a middling

size, made from two small-pine trees, that were driven on shore nearly

at the same spot."

The

log belonged to whatever chief ruled over that stretch of coastline where

it happened to be beached.

Menzies,

-Vancouver's surgeon and naturalist, while crossing the Kaua'i Channel

later reported "the largest single canoe we had seen amongst these islands,

being about sixty feet long and made of one piece of the trunk of a pine

tree which had drifted on shore on the east end of the island of Kauai

a few years back..

She

had sixteen men on her and was loaded on the outriggers with a large quantity

of cloth, spears, two muskets, and other articles, which they were carrying

up to Mau

Page 24.

Dimensions vary between 6 feet and 12 feet in length, average 18 inches in width, and between half an inch and an inch and a half thick. The nose is round and turned up, the tail square. The deck and the bottom are convex, tapering to thin rounded rails. This cross-section would maintain maximum strength along the centre of the board and the rounded bottom gave directional stability, a crucial factor as the boards did not have fins.

Any discussion of the performance capabilities is largely speculation. Contemporary accounts definitely confirm that Alaia were ridden prone, kneeling and standing; and that the riders cut diagonally across the wave. Details of wave size, wave shape, stance and/or manouvres are, as would be expected, overlooked by most non-surfing observers. Most early illustrations of surfing simply fail to represent any understanding of the mechanics of wave riding. Modern surfing experience would suggest that high performance surfing is limited more by skill than equipment. It is a distinct probablity that ancient surfers rode large hollow waves deep in the curl - certainly prone, and on occassions standing.

By 1000 A.D these

principles were confirmed...

13. Large waves

are faster than small waves.- a larger board is easier to achieve

take off.

14. Steep waves

are faster than flat waves.- a smaller board is easier to control at take

off.

15. Control is more

important than speed

16. Surfboards are

precious.

There are no contemporary accounts of how the boards were ridden, but it is most likely that the design was specifically for riding large swells on outside reefs, rather than on breaking or curling waves. In 1961, Tom Blake suggested that the Olo may have been ridden prone.

In the 1920's, Tom Blake and Duke Kahanamoku reproduced the design in a hollowed version to radically reduce the weight. See #5xx, below

| This third set also

includes a photograph of a selection of four surfboards and the caption

Illustrations, Third set, Plate , between pages 48 and 49. The image, right, is as reproduced in the 1983/1985/1996 reprint of Hawaiian Surfboard, retitled as Hawaiian Surfriders 1935. The image crops the tails of all the boards and the nose of Paki's board. The white scar appears to be a tear in the page from which the later edition was copied. |

|

|

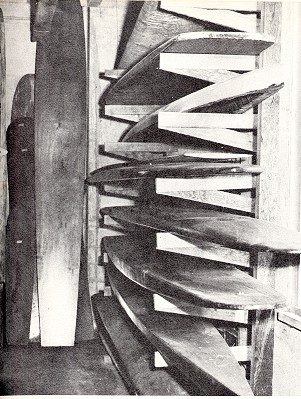

Image left

Bishop Museum Surfboard Collection, circa 1959. Photograph: Star Bulletin. HISTORIC COLLECTION

(Figure

1)

|

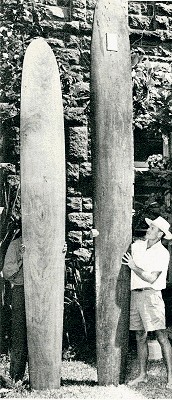

| Image right

Alia board and Paki's Olo, Bishop Museum Collection, circa 1959. Photograph: Star Bulletin SURFBOARDS OF

ANCIENT TIMES (Figure 2)

|

|